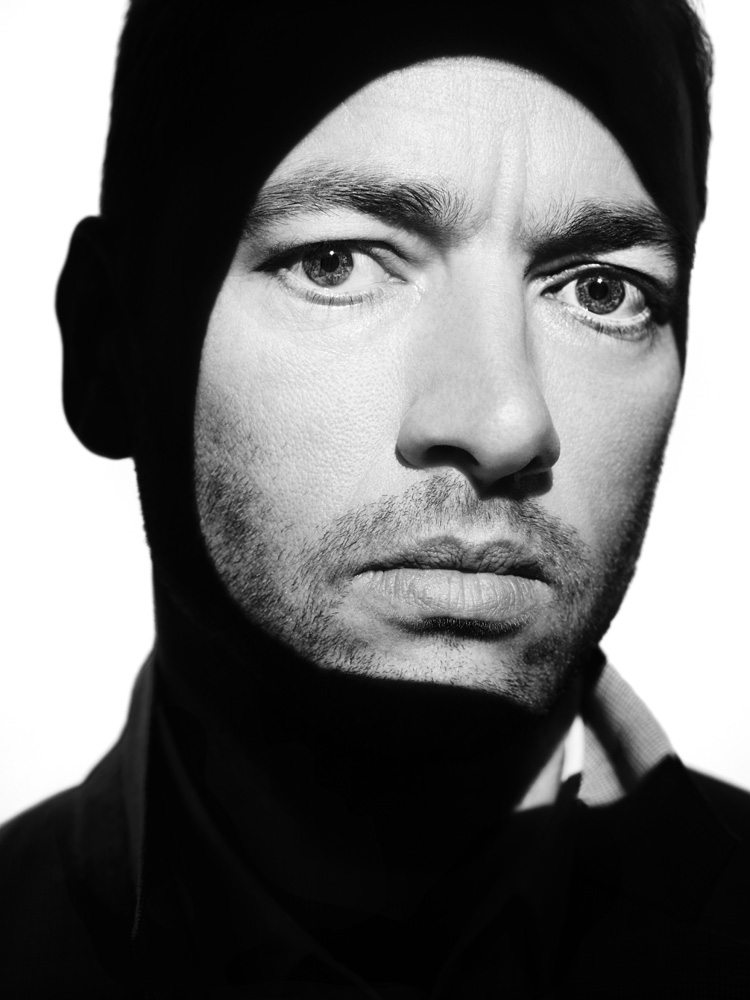

Sean Ellis

What was interesting is, after five minutes, you are so into it, [language] is not a barrier at all. The barrier becomes invisible.SEAN ELLIS

Drawing inspiration from a street altercation he witnessed between two gun-toting armored-truck drivers in the Philippines, British director Sean Ellis turned a bit of untoured vacation sight-seeing into his critically acclaimed new film, Metro Manila. Written in English by Ellis and screenwriter Frank E. Flowers, and translated to Tagalog by a cast of Filipino actors, the film follows a trusting family from poverty in the rice fields to the city, which threatens to swallow them whole when they fall into a con man’s trap and lose all of their money. While his wife, Mai (Althea Vega), takes work as a dancer at a bar, Oscar Ramirez (Jake Macapagal) lands a job as an armored-truck driver, but again falls prey to an unscrupulous character when his senior officer, Ong (John Arcilla), involves the father of two in an elaborate heist. Ramirez must then make plans of his own. Metro Manila won the Audience Award for best world dramatic film at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, and garnered the former fashion photographer wins for Best British Independent Film, Best Director, and Best Achievement in Production at the Moët British Independent Film Awards. In addition, the United Kingdom has submitted the film as its entry in the Oscars category for best foreign-language film.

Ellis is well familiar with the festival circuit, having previously won a number of top awards including the Tribeca Film Festival’s 2005 Best Narrative Short prize for his romantic comedy Cashback, which went on to score an Oscar nomination for live-action short. The 43-year-old filmmaker recently spoke with actress Noomi Rapace from his home in Cognac, France.

NOOMI RAPACE: Let’s talk about Metro Manila. When did the story come to you? Where did it start?

SEAN ELLIS: I went on holiday to the Philippines in 2007. A friend of mine was working out there and said, “Come out and we’ll have a week in Manila and go out to Boracay Island,” which is kind of like the Filipino version of Ibiza. I didn’t really know much about the Philippines, but I travel a lot, so I tend to not do much research on countries—I just sort of go to places and immerse myself in them and try to not be a tourist. I think when you do research, you generally get the tourist kind of travel tips. The first week I spent in Manila, one of my first culture shocks was the sight of guns. I mean, every store had a private security guard armed with a shotgun, and even the traffic wardens had shotguns. It was a sight that I didn’t really get used to the whole time I was there, even when I went back to film. Especially coming from England, where you rarely see guns—I mean, you might see police officers with guns at the airport, but that’s about it. While I was walking around the streets, I happened upon these two armored-truck drivers who were standing beside the truck having an argument. They were literally shouting at one another on the street, and I stopped and hid myself in a doorway and observed it. It ended with one of them kicking the truck—it looked like in frustration, like he was in a place of complete helplessness. And then they got in the truck and drove off, and I thought, Wow, because I thought they were going to shoot each other because they had automatic machine guns and were screaming at one another. And I thought I was given this weird gift, this idea. I tried to imagine what they were arguing about: two guys do an armored truck; one of them was blackmailing the other one into helping him do a robbery for the company they work for. So that seemed like a good idea. I tried to imagine: How could I get that guy into a position of blackmail? Why can he be blackmailed? So then I started to take the idea that he was less fortunate and needed the position, that he was a family man who comes to Manila, gets this job, and then is blackmailed by the guy he works with into helping with the robbery. And then, once I got that far, what was the robbery?

RAPACE: Did you research that?

ELLIS: Yeah, I did. You know, it’s hilarious—if you call an armored truck company and ask them how they operate, they’ll hang up the phone on you. [laughs] Nobody would tell me anything! They all think you’re nuts. So I thought, Wow, I could probably completely make it up and nobody would know any different. So I took some examples of stuff that I heard. I knew they use boxes with exploding dye packs, and that seemed feasible to me. So the idea that the thing you had to steal was not actually the money, but the key that opens the box to the money—that seemed fresh to me, and the thing that really felt fresh to me was the way that Oscar plans the robbery—I’d never seen that before in a heist movie. At that point, I got about 20 pages of the film, and it was pretty much the beginning, middle, and end.

RAPACE: Did you let people who knew about that kind of thing read it? Or did you just go ahead with your own instinct on it?

ELLIS: No. I had 20 pages and I went to L.A. and met with some of the people I knew who could help me finance it, and they sort of shook their head at me, “You want to go where? And make it in what language?” And I was like, “Tagalog, the Filipino language.” “Do you speak it?” “No.” They were like, “How are you going to direct a film in a language that you don’t speak?” And I was like, “Well, I did a short in French—which I didn’t speak at the time—and I really enjoyed the process.” So my plan to make Metro Manila was to speak to the actors in English, have the script in English, and then get the actors to translate their lines into Tagalog. Then when the camera was rolling, they would say their lines in Tagalog. What was interesting is, after five minutes, you are so into it, it’s not a barrier at all. The barrier becomes invisible because most of the language that we have is nonverbal. I know what they are saying because I have the English translation of it, but what I’m looking for is the emotional state, and I can see that without understanding the particular words. You stop worrying about line delivery or the way that a word is said, and you start to really see the performance. I mean, they call it “best performance.” They don’t call it “best line delivery.”

RAPACE: You can see it in the bodies and in the energy and chemistry between the characters. I didn’t speak English until a few years ago. Starting to learn a new language and think in a new language and act in a new language—in the beginning, I was kind of terrified, like it’s always going to be this big war between me and the language. But then, after a couple of weeks when I was doing Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows—it was my first English movie—I forgot that it was not my language.

ELLIS: Language is just the primitive form of communication, but if you are hitting a certain target emotionally, the actual performance would be the same in whatever language. So when directing Metro Manila, that was very much how I operated. I worked with the actors to really know where they were emotionally in the script and would just watch what they would do.

RAPACE: How did you find your actors? Did you do lots of castings?

ELLIS: After I realized that nobody was going to finance this film, I ended up going to my bank manager and basically getting a loan against my house. So I remortgaged my house and had to figure out how I could make it for the amount of money that I had. I knew independent film in the Philippines was quite strong, and I knew that they made independent feature films probably for the same amount of money that we make short films in Europe. So, once we landed, I started to do a budget and then I started to meet with cast, and Celine Lopez, my executive producer, said, “You have to meet Jake Macapagal because he is a theater actor here, and he knows everybody, and he will put you in touch with people.” The next day Jake brought a couple of actresses to read for the part of Mai and we put them on camera. I saw Jake on camera reading opposite as the husband, and suddenly I knew that he was the leading man. He sort of became on camera this man with the worries of the world on his shoulders. That night, we went to dinner, and I said, “Jake, I want you to be the lead in the film.” Of course, he was a bit taken aback and was like, “What? Really?”

RAPACE: He gave an incredible performance.

ELLIS: He was just a pleasure to work with. The performance from him is all to his credit. I don’t mind giving direction because every actor works differently, but when somebody is crafting it from the inside out, and they’re hitting it all the time, you just think, Wow. There were so many times when my mouth was literally open from seeing something that he’d done—and not just Jake, all the cast. There were certain things that I was capturing that I just knew … You know when all the traffic lights are green and you never have to stop? It is kind of that feeling: there are no red lights, there’s no stopping.

RAPACE: Were you ever afraid during shooting? Just watching the film, Manila feels like a city that might be difficult to just walk around in if you’re not familiar.

ELLIS: I think whenever you go to a new city or a new country that you have never been to, there is always that trepidation: Can I do this, or can I do that? I remember before we went to the Philippines, there was a news story about an actor who had been killed while shooting a scene. The scene was an assassination. The actor jumps on a motorbike and drives off, wearing a mask. As he’s driving off, a village watchman saw him brandishing a gun and shot and killed the actor. This is obviously one of the problems with having so many guns and so many private security guards in the country. So I was literally thinking that I am not going to make it back alive. Security was a really big issue for me when I landed, but then when we got under way and were moving around, I would ask, “Do we need security?” And they were like, “No, no, it will be fine.” Even though I was very worried going in, once we were shooting, the people were just super-friendly and the crowds that we drew were fascinated with the filming.

RAPACE: Did you have a team of Filipino film workers?

ELLIS: Besides myself and my co-producer, Mathilde Charpentier, all our crew was Filipino—our line producers, production people, assistant directors, gaffers … So in that respect, I felt very embedded in the culture and surrounded by people who I could draw on for information about accuracy and stuff I needed to know. But also they really helped in situations where we were amongst the public and when we were shooting guerilla—we didn’t have permits and so the Filipino crew was able to smooth out a lot of the problems that we might have had with people saying, “Hey, you can’t film here.”

RAPACE: You were a fashion photographer before you started making films, working with lots of big brands and models. When did you make the switch to movies, or are you still doing photography as well? How did that happen?

ELLIS: I do more commercials now for fashion clients, rather than stills. I made the switch to film full time in 2002. I became sort of disillusioned with fashion. My dream was to shoot for Vogue and do the sort of images that inspired me as I came up through the ranks. But I saw that fashion had become a very big business, and at that level there was not that much room for the creative imagery that I was really interested in. It’s become this multibillion-dollar business with clients to look after and campaigns to nurse. After doing a few fashion stories for magazines, I started to think it maybe wasn’t really what I wanted to do and wasn’t creatively fulfilling for me, so I started to move more into film because film seemed like I could have more ways of expressing an idea through telling a story.

RAPACE: Are you from a creative family?

ELLIS: No. My mom and dad were working class but always encouraged what I wanted to do. They never put it down. I lost my mom last year, and I remember one of the last conversations I had with her was actually about one of the defeats that I had during the post-production of Metro Manila. We got rejected from some festival that we had worked quite hard to get into, and it’s a shame because I would have liked to talk about one of its successes with her, do you know what I mean? But what’s great about that moment was that she was there for me always. She called it “my holiday film,” which was pretty sweet because she thought I went on holiday to the Philippines and made a movie. It was after I had done two other features that had a bit more studio backing. So she said, “How’s your holiday film going?”

RAPACE: Did your mom watch the movie?

ELLIS: Yeah. I showed her a rough cut before she died. She died of brain cancer, and she was a little bit affected by it, so her concentration wasn’t all there, but she did what she always did and said, “Oh, it’s fantastic. Well done. I am so proud of you.” I probably could have wet my pants and she would have said the same thing. [laughs] I think it affected my dad more. He was quite emotionally affected after he saw the film, and obviously that had a lot to do with what would happen to my mom and that we lost her. I remember sitting with my dad at the Sundance Film Festival when it premiered, and that was a lovely moment because he just held my hand, basically. I dedicated the film to my mom.

RAPACE: So, what’s next? Where do you go from here?

ELLIS: I don’t know. I’d like to say that I take some of the lessons with me to my next project and keep in the same direction.

RAPACE: What did you learn from Metro Manila? What’s the strongest thing you carry with you?

ELLIS: Never take no for an answer.

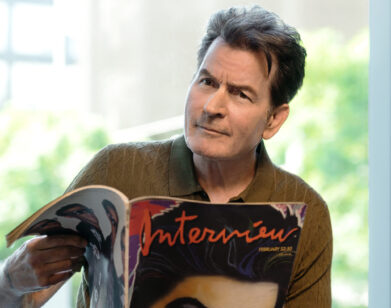

ACTRESS NOOMI RAPACE HAS STARRED IN PROMETHEUS (2012), PASSION (2013), AND STIEG LARSSON’S THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO. HER UPCOMING FILMS INCLUDE ANIMAL RESCUE AND CHILD 44.