Fashioning Sandy Powell

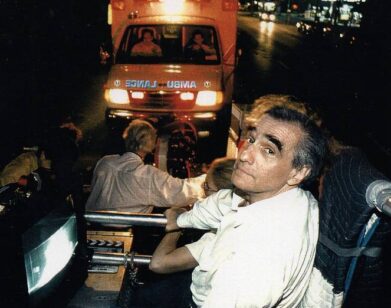

Clothing inevitably creates character. That’s something that Sandy Powell, the three-time Oscar-winning costume designer, knows better than most. She digs deep into the psychology of the personalities projected onscreen, much like the directors she works with time and again, like Todd Haynes and Martin Scorsese, or the late British art filmmaker, Derek Jarman, who gave Powell her first gig in film on the set of 1986’s Caravaggio, a fast-and-loose biopic of the Italian painter.

Over the last 30-odd years, Powell has engineered the courtier garb and pannier gowns that transformed Tilda Swinton in Sally Potter’s gender-transcending, period-shifting epic Orlando [1992]; the natty waistcoats of Boss Tweed crime boss Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis) in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York [2002]; and the full-skirted Stepford wife drag of Todd Haynes’ high-Sirkian ’50s melodrama, Far From Heaven [2002]. Powell has dissected and rebuilt historic figures like Sylvia Plath (Sylvia, 2003), Katharine Hepburn (The Aviator, 2004), and Queen Victoria (The Young Victoria, 2009), as well as the sartorial social codes that denote money, power, class, excess, and fantasy, perhaps none so outlandishly as in her last Scorsese collaboration, 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street.

This year, in addition to two Oscar noms, Powell also received two nominations for the Costume Designers Guild Awards, which will be announced tomorrow night. The first, Excellence in Period Film, is for Haynes’ lush, naturalistic ’50s lesbian romance Carol, an adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt; the second, Excellence in Fantasy Film, is for Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella. We spoke with Powell recently by phone, while she was at home in London, about exacting the perfect fur for Carol Aird, fashioning Cinderella’s evil stepmother as a Joan Crawford-like villain, and the punk aliens of John Cameron Mitchell’s upcoming How to Talk to Girls at Parties, slated for release later this year.

COLLEEN KELSEY: The last time you were nominated for the Oscars twice in one year was for Velvet Goldmine and Shakespeare in Love. At the time did you want one to win over the other?

SANDY POWELL: Ahhh, I can’t say. And do you know what happened? I was very lucky that year because I was also nominated for both films for the BAFTAs. I won the BAFTA for Velvet Goldmine and the Oscar for Shakespeare in Love, so that worked out neatly. [chuckles] No complaints that year.

KELSEY: Velvet Goldmine was the first time you worked with Todd Haynes. But you first got involved in costuming through dance performances, correct?

POWELL: My very, very first job out of college when I was 21 was with a dance company with a choreographer called Lindsay Kemp. I came across him because I knew he had worked with David Bowie during the Ziggy Stardust phase, so I’d heard of him and read of him. Then, as a 16-year-old, I went to see him and when he performed in London. From that moment on I was obsessed. [laughs] [My first production] was a ballet piece called Nijinsky, about the dancer, but I worked with him continuously over the next six years, and I’m still really good friends with him. It was a real extraordinary combination of dance, burlesque, theater, and mime. It was really everything, like something I had never seen before. Of course, doing anything with theater is completely different from working in the film world.

In 1984, I met Derek Jarman. I was working in the theater in London, and I met Derek and asked him to come see a piece of work I had done at the theater, which he did. Then he basically introduced me to the world of film from the moment of meeting him. Before working on Caravaggio [1986], which he directed and was my first film, I did a year of pop videos. He introduced me to producers in that world. I did a year of that, and before I knew it I was designing Caravaggio, not knowing what the hell was going on. [laughs]

KELSEY: What is your research process when you begin a project?

POWELL: Even though every project is totally different, and the things that you’re looking at might be different, it’s usually the same process. I obviously begin by reading the script, talking to the director about what they want, and if the director has additional material, I look at that first. Quite often they do, especially directors like Todd Haynes and Martin Scorsese who always come armed with piles of materials, which is brilliant. It’s a head start and it’s also a way into their head. You know where they’re coming from. If I’m looking at a period, I always start by researching that period thoroughly, whether it’s paintings, or photography from the period, and written material. I’ve got an extensive library of books myself, so I always start with that. And then, I go further into the field, whether it’s to art galleries, or libraries, and of course, the internet makes things a lot easier.

KELSEY: Cinderella is rooted in period dress, but there is a fantasy aspect. Where did you start with Lily [James], Cate [Blanchett], and the stepsisters?

POWELL: I guess the hardest one of them all, believe it or not, was Cinderella. It’s actually pretty difficult to do the good person without them being boring or cloying or twee, do you know what I mean? You have to be beautiful, you also have to be really simple so, it’s quite hard to narrow that one. Usually it’s much easier to go straight into the villain [laughs], because, more often than not, they’re more caricatured, more extreme, they’re easier to pin down. It was the stepmother that took over, first of all, because in a way it was easier to get material, and there were more areas that you could to look at. For her, I did go to the ’40s. Reading the script, I couldn’t get this image of Joan Crawford out of my mind: Joan Crawford with a big hat on.

So, I looked at ’40s films that were set in the 19th century and how they look. They still had the big ’40s shoulder, they still had the pointed bosoms, but with a resemblance of the 19th-century costume, that kind of noir way and melodramatic way. Getting on with the sisters, because they’re her kids, I thought of them as not being as severe as 1940s. I bumped them up a notch in the decade of the 1950s and looked at films made in the 1950s and set in the 19th century like Little Women and Pride and Prejudice.

KELSEY: I read in an interview with Todd Haynes that he first heard about Carol from you.

POWELL: I had met [producer] Elizabeth Karlsen, who was an old friend. We talked about what we were doing and how she had the rights to this book and how Cate Blanchett was onboard. A couple years earlier, I had read the book thinking this would make the most amazing film if only somebody would do it. Lo and behold, Liz had the rights. I said, “Well, I want to design it. I don’t care who’s directing it.” Originally there was another director. As time went on, things moved around. People weren’t available, and they lost that director, and I remember saying to Todd, “Oh my god, we’re doing this film and you should do it! It’s brilliant for you.” He was at the time, I think, doing something else, which consequently fell through, so everything fell into place. When I read the book for the very first time I thought, “This is a Todd Haynes film.”

KELSEY: What is your working relationship like with Todd?

POWELL: The start for Carol was obviously talking about it and his lookbook. He also provided music, the soundtrack, or his ideal soundtrack, so you really are very much immersed in the world when you begin. We didn’t have a great deal of time to prepare for Carol. It was done very quickly, so I had a few meetings with him. Quite often his books are about atmosphere specifics, so I just soak it all up and don’t think too much about it in a way. I trust my instincts. As soon as you meet an actor and you try things on, I get an idea very quickly as to what’s going work and what’s not. Then I show Todd all the fitting pictures, and we talk about them, and he’ll express his opinions. We screen-tested what we had at the beginning, and then there comes a point when everybody can see the characters emerging from what they’re wearing, from hair and make-up, and it all comes together. It sounds easy, and actually it is really easy working with Todd, because his communication is so clear, his information is so clear. We’re on the same wavelength. I think it’s much about that as it is anything else.

KELSEY: The naturalism of the period’s street photography was a reference for Todd and [cinematographer] Ed Lachman. Did it direct the clothing as well?

POWELL: The street photography was very useful for the background, for the actual world they came from, looking at the people on the street. The bits that are important are the silhouette, the shape, and then I got the head, the shape of the coat, the heels, and the shoes. It really helps to narrow down what is necessary. You could filter out the things that aren’t needed, especially on a film where people are moving around. It’s really good for the background, because it’s an ordinary looking background, it’s a variety of people. For specific characters like Cate [Blanchett]’s character, Carol, I looked much more at fashion because she was the one person in the film who was absolutely up-to-date fashion-wise. I did look at copies of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar from the months the film was set in, December ’52 through to April ’53 or so.

KELSEY: Which is quite a transitional time, fashion-wise. It’s not the high ’50s yet. The ’50s of Carol is a very different ’50s than Far From Heaven.

POWELL: Exactly. A lot of it is the ’40s, a lot of the background and secondary characters, are basically late ’40s. I would say Carol really is about the only one who was bang on, fashionable, 1952.

KELSEY: I wanted to discuss two key looks, which make big sartorial statements for the characters in the film: Carol’s fur coat, and the tailored suit Therese wears at the end of the story, when they are reunited. I read that you were very particular about the exact color of fur for Carol.

POWELL: It’s described in the book and the script that she’s in a fur coat. It’s described as voluptuous and luxurious; it’s not described much more than that, I don’t think. I had this feeling that it was absolutely crucial for that meeting in the department store, she had to be noticed from afar. It’s 1952; it’s winter in New York. There’s a lot of people in fur. It’s fashionable. Mostly the furs are mink and they’re dark colors. I felt it needed to be a note and an air of luxury and wealth. A lighter color somehow exudes luxury. Also, she’s blonde. It was a flattering color and I wanted it to standout without being flashy. Once I decided that, I found vintage coats. They were all the right shape and the rest of it, but the wrong color. I tried them on, and the shape was good and it looked good, but there was something wrong. Then I found a light-colored coat that was the wrong shape and I thought, “The color works, the shape is wrong.” By the end of it, I just had to make it the right shape in the in the right color.

We made Therese’s suit from scratch and I really had to think long and hard about that. I knew that her silhouette was not going to be the same as Carol. She’s younger, and I wanted her to have a fuller skirted shape that was more based on the [Dior] New Look, but the fitted jacket and the full shoulders were very much along the same lines of the things that Carol wears. It needed to be a suit, a dress suit, and it needed to a one-up from what she’d been wearing before. It was a mixture of her finding her own voice and her own sense of style, yet being inspired by the sophistication of Carol.

KELSEY: Have you wrapped John Cameron Mitchell’s How to Talk to Girls at Parties?

POWELL: We finished shooting in December. It was crazy good fun. It was one of the maddest things I’ve done in a long, long time, really since the ’80s. It’s set in 1977 against the backdrop of punk in Britain, so we had real punk to do. I don’t think it’s been done on film before. Then we had like 40 aliens, which I shouldn’t tell you too much about, because I can’t spoil the end. But it was mad, mad fun. Incredibly low budget. Really hard work, but everybody working on the film was doing it for love.

THE COSTUME DESIGNERS GUILD AWARDS ARE TOMORROW, FEBRUARY 23.