Todd Haynes

Painstakingly constructed settings are usually reserved for epic science fiction fantasies where directors have unparalleled freedom to create digital environments, but there are no superheroes in a Todd Haynes film—just empathetic, flawed human beings acting out their lives in minute period detail. Haynes became a cult icon when his 43-minute short film Superstar (1987), the tragic saga of anorexic pop star Karen Carpenter told using Barbie dolls, was banned from circulation because of copyright issues. (Bootleg copies can still be viewed on YouTube.) Haynes, who was born in Los Angeles in 1961, has been tweaking societal conventions ever since. As a pivotal member of the New Queer Cinema movement, he enraged conservative politicians with frank depictions of gay sex in Poison (1991), then upended his own audience’s expectations four years later, with the jarring hypochondriac drama Safe (1995). Subsequent films such as Velvet Goldmine (1998), Far From Heaven (2002), and I’m Not There (2007) manage to embrace both experimental and formal aims, like academic theses wrapped in sweeping, melodramatic arcs. Throughout his career, the director has explored how women have navigated visible and invisible levers of power. “I’m drawn to female characters,” he tells Kate Winslet, his self-professed “other Coen brother” and star and co-producer of his new HBO miniseries, Mildred Pierce. “And not all of them are strong characters.” Airing this spring, the five-part miniseries tells the story based on the novel by James N. Cain, of a resilient but imperfect woman who struggles to raise a family in Great Depression–era Los Angeles. Winslet recently spoke with Haynes, who was at his home in Portland, Oregon, about, among other things, Mildred Pierce, why he’s never made a film set in the contemporary world, and the challenge of letting things go.

KATE WINSLET: Do you remember the experience of watching your first ever movie?

TODD HAYNES: I do. I was 3 years old and it was Mary Poppins [1964] and it made an impression on me that was seismic, apparently. I fell into some kind of total creative, imaginative rapture over that movie that propelled this industry of Mary Poppins drawings, plays, performances—just an obsessive, creative reaction to it.

WINSLET: Do you think that your expectations for movies beyond that moment were amplified?

HAYNES: Yes.

WINSLET: So did you subsequently feel let down if something didn’t give you that same internal punch?

HAYNES: No, I don’t think I was let down. Other movies along the way would seize me in similar ways and would usher in a whole new phase of sort of obsessional interests. After Mary Poppins, it was probably the [Franco] Zeffirelli Romeo and Juliet in ’68. I was 7, and it completely blew my mind and I went into this sort of Shakespeare obsessional period. And then later, movies like The Miracle Worker [1962] or Anne of the Thousand Days [1969]. A lot of them, interestingly, were English in setting and subject [laughs] whatever that means. What was your first one? Do you remember?

WINSLET: The first film that I remember having a really profound impact on me was The Red Balloon [1956].

HAYNES: Oh wow, that’s a cool one.

WINSLET: I know. I’m kind of proud of how cool that is. [laughs] But the reason why I remember watching it is because I was ill off school and I was at home and my dad was with me, taking care of me, and it was just on television. It was the experience of sitting and having that one-to-one, very special time with my dad. I was one of four siblings, and so one-to-one time happened very rarely with either parent. And particularly not with my father, because he was always out working, whether he was working for a tarmac firm, or the postman, or doing whatever he did to make ends meet. Or acting jobs, which were very few and far between anyway. And just recently, because I remembered that experience, I sat down and watched The Red Balloon with both Mia and Joe and they both were moved to tears by it. They really grasped the concept, that just one thing, so unique and so beautiful can make you so happy and change your entire perspective of the world and your day-to-day existence. Would you like to direct a film set in more contemporary times and is there a specific reason why that hasn’t happened in your career?

HAYNES: I continue to think about historical moments and periods as inspiration and subject matter, and yet, everything that occurs to me has some relationship to what’s going on today. I guess I’ve always felt that when you see material through a frame—and for me that period or that historical setting is a frame—it allows a viewer to make their own connections to why it’s relevant.

WINSLET: I’m realizing that you really only make a project once every what, four years? Five years?

HAYNES: [laughs] Something like that, yeah.

WINSLET: Someone like [Steven] Soderbergh is known for working at a fairly fast pace and that works for him, and Baz Luhrmann is known for working on the opposite end of that spectrum. Where do you feel you fall?

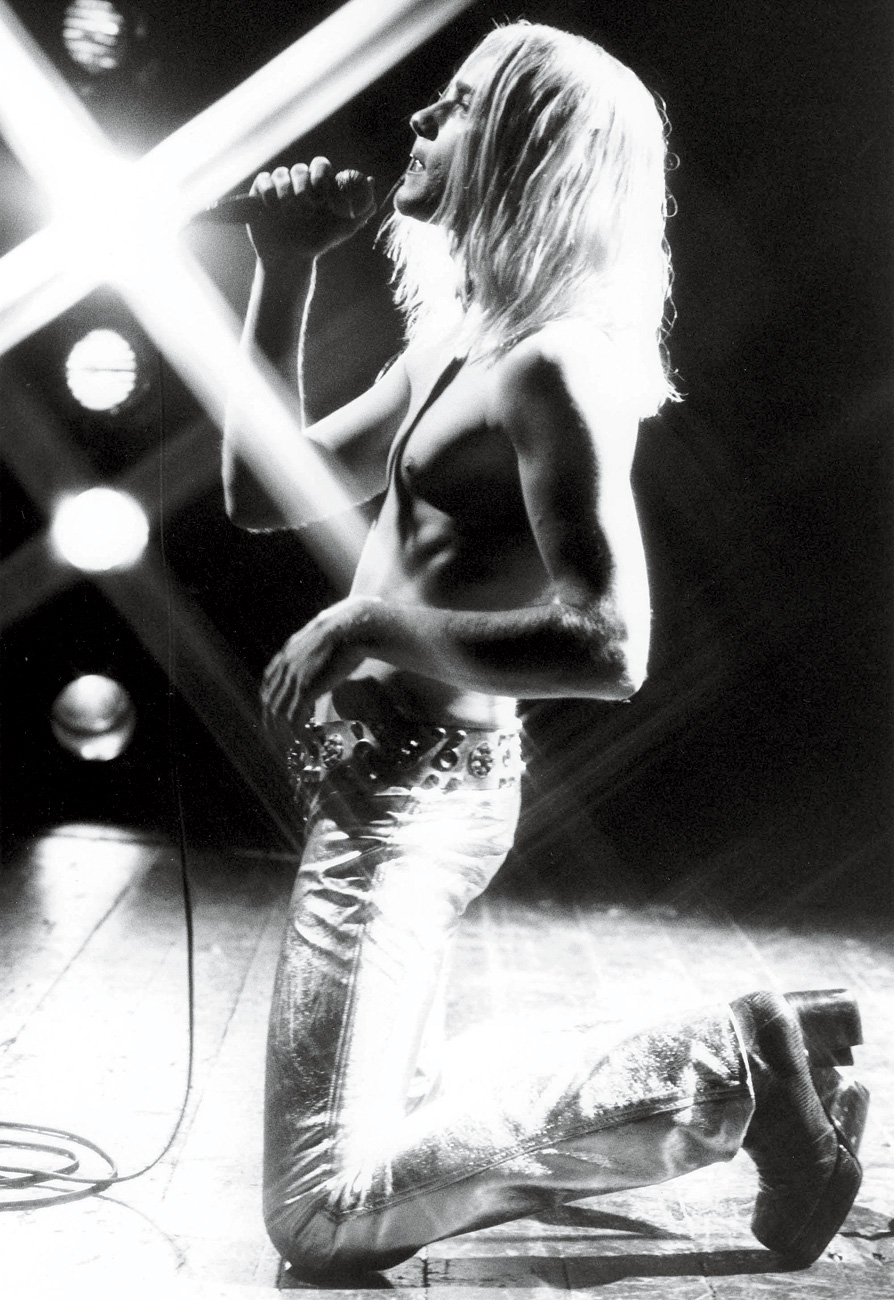

HAYNES: I think it’s due to the dogged single-mindedness that seems to be required for me to produce something as complex and demanding as a film, especially ones I’ve written and directed. And as an independent filmmaker, to develop the money and the financing and the structure and the whole process, and then promoting them and traveling with them, which is a part of the process that I’ve always enjoyed and I’ve learned a great deal from. I really do like seeing it all through, starting from the very beginning, which often entails years of research on a subject. Someone like the Bob Dylan subject for I’m Not There required what I felt was almost a dissertation on somehow trying to get close to encompassing his life and story and the historical influences that affected him and his work and all of that. I feel like I’m the same with the sort of glam era for Velvet Goldmine, and all the various artists and influences that produced that moment. So yeah, it becomes a kind of totalizing experience for me, and it doesn’t ever feel like there are big, long periods of inactivity between projects, it just feels like that’s the necessary lifespan of a single work, when you’re really the person generating it.

WINSLET: When you were a child, did you always want to direct? Did you ever consider doing anything else? Was there another passing fad or anything?

HAYNES: It was kind of a big bubble of interest in the arts in general, and in visual art all along, drawing and painting and stuff, but I always loved theater and acting in plays and directing, writing little plays and directing friends in plays. And I think when I was about 6 or 7, I would have said I wanted to be an actor and an artist. And that just kind of kept honing itself around film and getting closer to film. I remember seeing The Graduate[1967] when I was a kid, and as I became more sophisticated and began to see films, all the films that were coming out in the late ’60s and early ’70s were evoking a kind of zeitgeist of the times . . . the excitement of how a lens can tell a story and what was possible and a new sensibility about how to tell stories visually were as much about what you excluded from the frame as what you included. There was a new minimalism and a new shorthand in visual language that I remember feeling so stimulated by, like, through my entire body, and I would walk around looking at the world literally through frames. I think by around the time I was about 8 or 9, the idea of filmmaking probably took hold. I made little Super 8 extravaganzas when I was a kid, the first being my own version of Romeo and Juliet, and where I played all the parts except for Juliet. My mom even shot a Super 8 test roll in double exposure, because I wasn’t sure if I could find a good Juliet, so I dressed up as Juliet.

WINSLET: “I wasn’t sure if I could find a good Juliet.” [laughs] I love the exacting standards, even in an 8 year old.

HAYNES: There’s this footage of me as Romeo on one side of the frame, and pop, I pop on as Juliet on the other, in drag.

WINSLET: How about some of your early experiences of working with actors? Do you remember being struck by how unpredictable that can be?

HAYNES: I remember probably more vividly the experience of making my first feature, Poison, which was done in New York City, because we needed such a range of acting styles, so we put ads in Back Stage magazine and interviewed tons and tons of working theater actors, and it was a combination of people who’d worked in film, people who’d worked in theater, complete newcomers, and not actors, and that process was so rich and exciting and interesting, and we literally, at one point in the film, wanted a bum off the street, and we went to the Bowery and we pulled this guy up into our office and paid him to play this sort of perverse Jean Genet–influenced angel, and shot him in a couple hours, and then sent him on his way with some money in his pocket. . . . But I don’t think it’s until you learn, until you work with nonprofessionals, and get good stuff out of that process that I think you really understand the whole range of what’s possible and how there is no single style of acting. And there is no single approach that actors take to their craft. And the best thing you learn is that you have to really listen and respect each actor’s own process and own method, and that takes a kind of delicate, you know, non-imposing patience and openness, I think, to get the very best out of the people you work with.

WINSLET: Hey, we were fortunate that we got along, Todd.

HAYNES: Oh my god, Kate, can you imagine? I mean it really worked out, so I felt like I had my other Coen brother, you know? [both laugh]

WINSLET: Oh my god! That’s such a huge compliment, that has to go into this piece. Okay, some of your movies feature women as the protagonist. Do you think that you are particularly drawn to strong female characters?

HAYNES: I’m drawn to female characters, not all of them are strong characters. I think I’m drawn to female characters partly because they don’t have as easy or as obvious a relationship to power in society, and so they suffer under social constraints or have to maneuver within them in ways men sometimes don’t, or are unconscious about, or have certain liberties that are invisible to them. And those accesses to power are never invisible, they’re always a struggle. The ways that those sort of ambiguities are internalized are extremely interesting to me as well. Mildred Pierce is such an amazing example, because unlike most domestic dramas, where it’s about women contained within very rigid domestic settings and suppressed by their role as wife or mother, this is a woman thrust out into the world, newly single, with two kids to raise in the Depression in Los Angeles who has to find her way. And the way she functions, her unbelievable skills and drive and industry as a person and how her own, even emotional pathologies around her daughter get translated into productive work and amazing success and all of that, I just find an unusual female character and story and one I’d never really encountered before. I think it’s very rare in the pantheon of women’s films and women’s stories. I mean, you’ve played a lot of different characters with unique, surprising strength and grit and access to their desire and erotic sides and so forth, but I don’t know if you’ve ever played someone exactly like this.

There was a new minimalism and a new shorthand in visual language that I remember feeling so stimulated by. . . . I would walk around looking at the world literally through framesTodd Haynes

WINSLET: No, I haven’t at all. One thing I realized as we were shooting was that Mildred has so much strength, but also so much weakness that she learns how to disguise and moderate. And at the same time, her weakness does come out. Somehow she manages to turn those weaknesses into strengths, or projections onto her other relationships—in particular, her relationship with Veda [Mildred’s daughter, played by Evan Rachel Wood]. It’s her strongest point and her weakest point.

HAYNES: Absolutely.

WINSLET: She knows how to raise that kid, she knows what she believes in, she knows what she wants for that child, but her weakness, her massive Achilles’ heel is the fact that she loves her to a fault, that she can’t help herself and also wishes on some level that she too could be like that kid.

HAYNES: Yes.

WINSLET: Which is not a good thing for a parent to feel.

HAYNES: No.

WINSLET: And obviously, it ultimately came back to become one of the single most destructive things in her life.

HAYNES: Yeah, but along the way, becomes this incredibly productive thing.

WINSLET: Yes.

HAYNES: And on both sides of that spectrum it’s stuff she doesn’t see. I think it’s so interesting when characters don’t see things in themselves, because it actually again asks the audience to see for them and to see things they don’t see yet and it creates a really empathetic relationship and then that’s something that creates an element of suspense throughout this story, because she’s so capable, she’s so extraordinary in so many ways, and there are many things she does see or does come to learn about herself. But then the most persistent, or the most sort of ravaging, are the ones she doesn’t see until the end.

WINSLET: I want to talk about what has been the most difficult film for you to let go of emotionally, because I know as an actor there are key ones for me, but I wonder if it’s the same for a director.

HAYNES: Each one becomes such a total physical immersion and I’m sure a kind of psychic development of my own self as I go through those films. By the time I finished Poison, the New Queer Cinema was branded and I was associated with this. In many ways it formed me as a filmmaker, like as a feature filmmaker I never set out to be. I figured I would be teaching my whole life and making experimental films on the side. In many ways, the emergence that New Queer Cinema designated was an audience that had always been part of the art house audience but was suddenly distinguished as gay or queer or whatever, and that became a way to generate a product for this new audience that was aware, that was politicized, that was obviously literate and culturally savvy. And they could take films that were different and were challenging and were trying out different things. But by the same token, I was so eager to move on from it and do something quite different in my second film, Safe, with Julianne Moore. We would take it to gay film festivals because it was the second film by the gay filmmaker or whatever and people were like, “What the fuck is this?”

WINSLET: Yeah.

HAYNES: I found that film to be just as much an indictment of hetero-normative society as Poison was, but without gay characters as the subjects. It was still coming from me. It was still my perspective, it just didn’t have sexy abs in it, you know what I mean? I guess I fancied that I was ready to move on from these films, and in fact you never really are. They’re things you create, they’re things you love in different ways and they never leave you.

WINSLET: This is my last question.

HAYNES: All right.

WINSLET: You haven’t always been in a position to have a rehearsal period on films, but we spent almost two weeks on Mildred. Were you surprised by the ways in which that may have helped you? Do you think you would like to repeat the rehearsal process on set?

HAYNES: Oh god, absolutely! Wasn’t it incredible? It was so essential for something this massive. Five-and-a-half hours of dramatic material, and a ten-year span of a character’s life that we were shooting every which way, as always in low-budget filmmaking. It was so psychically grounding. The kinds of work that started to happen in those sessions continued to develop, even when you weren’t with other actors, but it planted seeds that continued to take root and grow throughout the process. Having the idea of rehearsals made me think I could do everything in the rehearsal time, and basically, we never left the table. But there was so much to discuss and so much to deal with just at the level of text and the level of character and backstory and relationships that aren’t depicted, and exchanges that don’t come out in the actual scenes in the film, but that provide their backstory. It creates a history, you know, that you carry with you, and keep applying, on camera.

WINSLET: I thought it was particularly important for the children because it’s so intimidating. Knowing that you’re playing a big character and you’re going to have to learn your lines and be in a room with all these people who, you know, apparently know what they’re doing. One of the things that we were both able to share with them is how important mistakes are. And how we love mistakes.

HAYNES: Yeah the misspeakings and fumblings and mumblings are these characters.

WINSLET: But we really did want to know: What did they think their character would do? What would they do at home sitting round a dinner table? Would they reach across to grab the orange juice jug? Little things like that made a big difference because, of course, it did move so fast when we got into the room and they felt as though anything that they did was of value to the whole project.

HAYNES: There’s a real family life, you know, buzzing along, on camera. It’s really extraordinary. Kate!

WINSLET: There you go, babe.

Kate Winslet is an Academy Award–Winning Actress who stars in the title role of Mildred Pierce.