Director

Zendaya and Sam Levinson Unpack Everything Malcolm & Marie

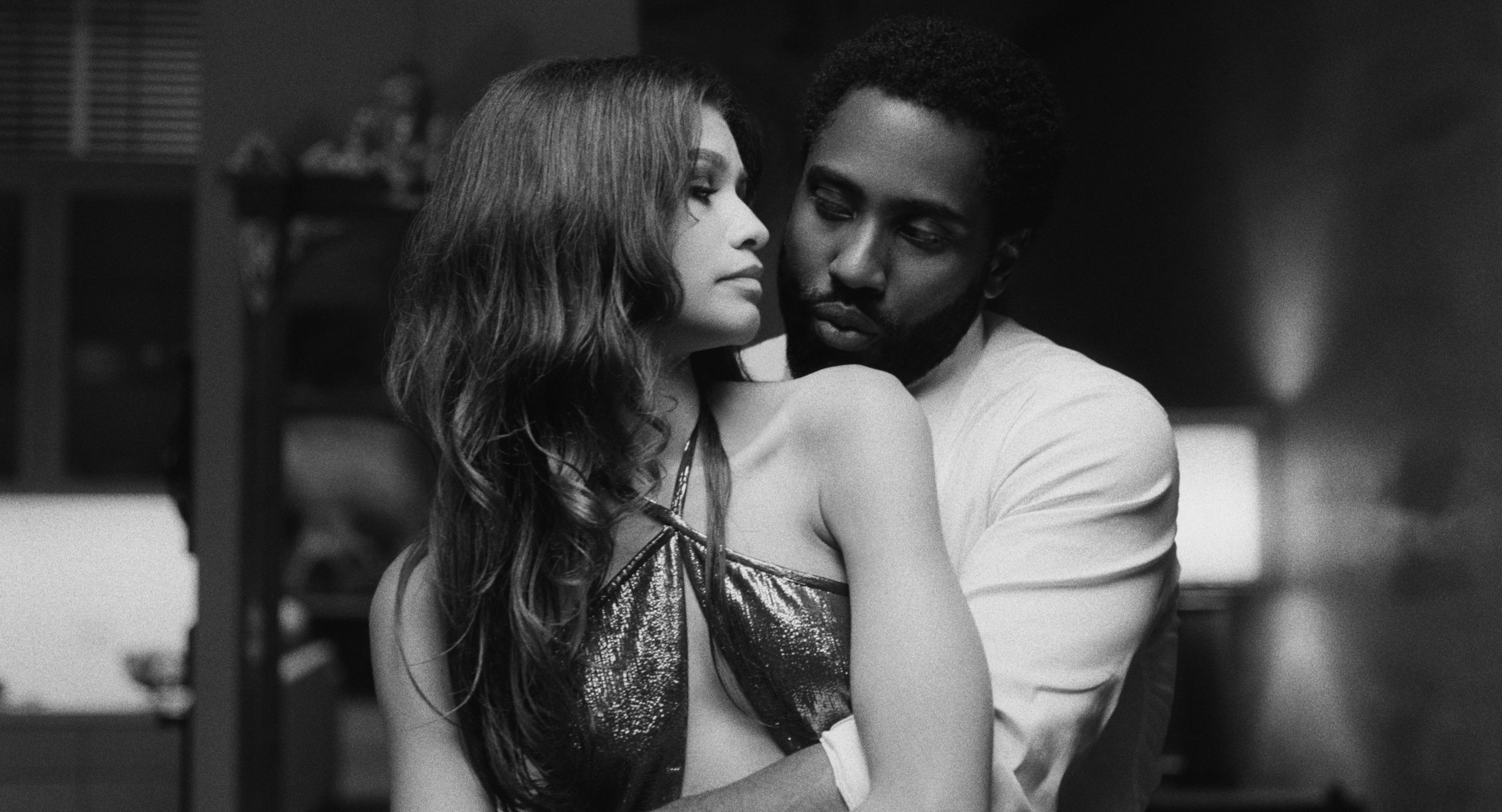

MALCOLM & MARIE (L-R): ZENDAYA as MARIE, JOHN DAVID WASHINGTON as MALCOLM. NETFLIX © 2021

Back in July, headlines were made when it was revealed that Zendaya and John David Washington filmed a movie in the early months of quarantine. Written and directed by Euphoria creator Sam Levinson, Malcolm & Marie was one of the first major projects to shoot under lockdown, and for a while, it seemed like the unique circumstances of its production would drive the conversation around it. But now that people have had a chance to see the movie, which was released on Netflix last Friday, Levinson’s two-person character study has sparked debate online about everything from the nature of film criticism to the age difference of its two leads.

Shot in one location and entirely in black and white, Malcolm & Marie introduces us to its title characters as they return home from a movie premiere. Malcolm is a writer-director on the rise, and his new film, about a young drug addict, is about to be released into the world. The movie is based on Marie’s life, something Malcolm forgot to acknowledge in his thank you speech. That touches off an argument between the two that makes up the bulk of the film, and, through his characters, allows Levinson to explore themes of authenticity, acknowledgment, film criticism, art, ego, and of course, love. Last week, ahead of the film’s release, Zendaya hopped on a Zoom call with her collaborator to recall the making of the film, and to unpack some of the reactions to it.

ZENDAYA: Hey, Sam.

SAM LEVINSON: Hey, Z.

ZENDAYA: I ask you a lot of questions on a daily basis, so a lot of what I’m going to ask you I already know. But maybe the world should know, too.

LEVINSON: I’m a little nervous now, but sure.

ZENDAYA: I’m going to start with your process. How does your brain work, Sam?

LEVINSON: I love collaboration. If I wasn’t interested in collaboration, I’d write novels. What I love about writing in general is that I can write a character and I know that an actor is going to bring their whole life to that character–what they relate to and what they don’t relate to. And out of that, through all of our discussions, we’re going to find what feels honest and right and true. Even with Rue [Zendaya’s character in Euphoria], there were a lot of conversations that you and I had, or thoughts or opinions that you had about the character, despite not having been an addict. I think Malcolm & Marie, more so than any other piece I’ve ever worked on, embodied that idea. A lot of the discussions that you and I had about life over the past two years, about collaboration, about representation, about the film industry, found their way into this piece. What makes filmmaking an unusual and rare art form is that it is this collision of identity in the search of universality. On a practical level, we go back and forth. I’ll rewrite lines, or I’ll be on set, throw a whole scene out, and start from scratch.

ZENDAYA: That’s the fun stuff. When we were literally in the middle of something and it was like, “This isn’t working.” It was the “only in America hoe-ass shit” part. The way it was originally written it wasn’t flowing right, remember?

LEVINSON: It felt stagy and fake. I love being wrong about something on set. I’ll give you a note or I’ll give J.D. a note, and it’s just the fucking worst note. Everything takes six steps backwards. And then I love going up to you after the fact and saying, “Go back to what you were doing, I think I was wrong about that.” As soon as that happens, everyone knows they have the right to be wrong, and that’s where the spirit of experimentation comes from.

ZENDAYA: It’s very rare that we’re not on the same page, though.

LEVINSON: Which is good. Because if we had differing opinions on everything, I think we might be in trouble.

ZENDAYA: The special thing about the way you work with your actors is you have this level of trust in us, even if we don’t really know if we have it. You’re like, “No, you got it,” which is that extra confidence you need. You’re also very empathetic. That’s why you’re able to listen and write the way you do, because you feel things on a very intense level. So when we’re going through the motions, often you’re going through them, too. If I’m crying, you have probably cried with me right before I went to go cry about it in the scene.

LEVINSON: Because I have this weird belief that if I’m behind the camera and I feel something, that somehow you can feel that I’m feeling it, too. So I’ll play out the whole emotional arc of what I hope to see, in the hopes that somehow energetically you feel it. Which is totally nuts.

ZENDAYA: It totally works. What is the process of writing a character? How do you take what’s true to you and then put it in someone else?

LEVINSON: I’ve always related to and seen myself more in women than I do in men. Why? I don’t know. That’s, in part, responsible for Euphoria. But at the same time, writing in general is this act of faith in our commonalities as human beings, so I always try to think of it from the perspective of whatever truth I feel and I put into a character, I hope that other people can feel it or see themselves in it. I also see identity and gender and orientation from a slightly more philosophical standpoint. What I mean by that is I think Malcolm, in some ways, is a stereotypical female character and I wrote him that way. He has these extreme emotional swings and needs to be needed, I think, more than Marie does. And those are attributes that, whether right or wrong, you would normally ascribe to female characters. And at the same time, Marie is a very male character in some ways. There’s a stoicism, a withholding nature to her that you would normally associate with a male character. And only as the film unfolds do you see the emotionality within. I think that’s what makes the characters unusual and exciting. So I try to find those emotional links, between myself, between the actor, between the character and build it in that way. And I also have a lot of faith in your ability to bring your perspective to it, or J.D.’s ability to bring his perspective. There’s always that thing when you’re writing and you imagine what it’s going to feel and look like on the screen. And I always love that moment in a table read or on set, where suddenly you go, “This is way better than I ever imagined it.” And that’s only possible because of the actors.

ZENDAYA: We talked about that often, too, especially when it came to John David. When you first called him and you had very few pages, you called me back after talking to him and I was like, “What did he say?” You were like, “He was asking these amazing questions. He was asking about had they ever thought about marriage?” I was like, “Damn, I didn’t even think about that.”

LEVINSON: “How long have they been together? Did they have a family?”

ZENDAYA: Right. Or even things that were so specific that I never would have even thought to think about yet. And I honestly think you hadn’t thought about at all either, because I remember you being like, “I didn’t have a fucking answer yet because I’m not that far in writing it.” I remember then we had this whole conversation about codependency and does she need him and is she relying on him? Does she have her own money? Does she have her own life? He brought that to it. And then also I think the humor. I remember when we did early readings, he just found such a comedy to it. We always thought the movie was funny, and I believe, in a strange way, that this movie is a comedy.

LEVINSON: I totally agree with you.

ZENDAYA: His physicality, even on set with the mac and cheese stuff, I remember just dying with you on the side watching him do that stuff. It was hilarious. Or you yelling out lines and him making stuff up. He was just freestyling.

LEVINSON: Most of the dailies of Euphoria are just me yelling out lines off-camera and then seeing what happens. I think that’s the fun of it. You want life and the unpredictability of things to seep in because that’s what makes something feel alive. You throw out a line and then an actor runs with that idea and three other lines come out that are just a hilarious train of thought. That’s the fun shit.

ZENDAYA: We’re honest with each other and I think that is crucial. If there’s something you write and I don’t buy it, I’ll tell you, “Sam, I’m not feeling it.” In the same way that if I’m not giving a performance that feels honest or you can tell that I’m overthinking that I’m in my head, you’re very quick to be like, “What’s going on here?” And speaking of honesty, I have to bring up the criticism criticism, and people assuming that it’s a little bit biographical in the sense that maybe this is exactly what happened to you with Assassination Nation or something like that. But I know for a fact that you didn’t get a review this good.

LEVINSON: That’s the whole irony to that interpretation, because Malcolm doesn’t get a negative review, he gets a fucking fantastic review. But it’s not the right kind of praise in his mind so it completely unmoors him as a character until he’s screaming at the trees about identity. The scene is about his insecurities as a filmmaker and how crazy he can get when he’s just in his own world. And I think to further compound it, Marie agrees with the film critic’s criticism and even takes it a step further by saying, “Well her problem with you as a filmmaker is my problem with you as a human being.” Which I think gets at the larger theme of what the film is about, which is learning to listen to critique and grow from it, not just as an artist, but more importantly as a human being. But it is fascinating that certain people’s interpretation of the film completely negates Marie’s counterpoint, which I would argue is the emotional core of the film. And I think in some ways, they’re essentially mirroring Malcolm’s dismissal and refusal to listen to Marie and acknowledge her validity. And that’s kind of bizarre and ironic and terrifying and interesting and what makes film in general interesting.

ZENDAYA: It is. There are some things he says that are valid but it’s about how he goes about doing it.

LEVINSON: He goes too far.

ZENDAYA: Which is the point. If he doesn’t take it too far, she can’t later say, “That’s my problem with you, is you just take shit too far. You don’t know when to stop. You don’t when something is good, you don’t know how to listen. You don’t know how to take criticism.” She’s like, “I’m sitting here and I’m telling you these things,” and I always looked at that as a peek into their relationship. Like okay, how many times has he gone on a rant like this and just hammered a point home and screamed at the trees? How many times has he done this when they were shooting? And it lets you in a little bit on how they coexist and gives you further insight into that.

LEVINSON: But that’s also the film critic’s one criticism of his film, is that he took one scene a little too far. Which is what Marie completely agrees with. She even says, “It was my favorite scene in the script. But not in the movie.” It serves as the jumping off point for what is essentially her 20 minute breakdown of Malcolm’s issues.

ZENDAYA: His narcissism.

LEVINSON: Yeah, narcissism and issues as an artist and a human being.

ZENDAYA: That’s his issue. He thinks he’s beyond criticism. That he’s above being able to be wrong.

LEVINSON: Right. And the line about, if you steamroll everyone in your midst, you’re going to end up creating a fictional reality where you’re completely insulated from any critique.

ZENDAYA: Any perspective that isn’t your own.

LEVINSON: It’s that whole thing about don’t believe the hype or else you’re going to make fake movies about fake people and fake things, because you’re not going to know what it’s like to live life because you’re never going to hear a perspective other than your own.

ZENDAYA: It’s interesting to watch how things reflect and mirror the movie in that way. What’s been really interesting is everybody who watches it leaves with a different takeaway that maybe we didn’t see. A special thing about this film is that there is no real resolution. What is the reasoning behind that? What do you want people to leave with? Is there a clear winner? Who’s side are we on? Should they be together, should they not be together? How do you view that?

LEVINSON: Who wins? I think Marie wins. Who’s right? I think Marie’s right. I think that’s evident in the final scene and that 20-minute monologue. It essentially grounds the entire movie in her perspective. But I think at the same time, the film is this Socratic dialogue between these two characters—about relationships, about filmmaking, about art, about partnership, about acknowledgement. And my hope is that people leave with whatever interpretation makes sense to their life. Whatever they see in the relationship that they want to take away from it, they will. Is the relationship healthy or toxic? I have no idea. I go back and forth on it.

ZENDAYA: I will go on record and say that I have never seen you and Ashley [Lent Levinson, Sam’s wife and co-producer] so much as even have a disagreement. You guys just work so well together. She is the conflict-solving queen. If there’s an issue, she’s like, “No problem. We’re going to sort it out.”

LEVINSON: But what’s weird about right now in terms of how we look at and view film and television and characters is that people go, “Is writing a character an endorsement of their actions?” Which is so strange because no, I’m not endorsing the characters who I think do things right and I’m not endorsing the characters who I think do things in a wrong way. They are who they are. They’re characters. Everyone else can decide what’s right or wrong for them. But there is this weird thing of, “Is this you? Is this not you? Is this the actor? Who is it?” There’s this desire to trace the roots of everything.

ZENDAYA: Or that there’s a message.

LEVINSON: Or that there’s a message. I think that’s just the nature of right now, where everything feels like it has a message in it that’s concrete, that people can walk away with and go, okay, this is exactly—

ZENDAYA: How I feel, yeah.

LEVINSON: Yeah. It’s political ideology or philosophical ideology. Whereas I think the message of this film is simply that you need to acknowledge the people in your life who help create the life that you’re able to flourish within. Whether it’s inside or outside the industry, that it’s one of gratitude. And it’s also what happens when you take for granted people’s love and contribution. That’s it.

ZENDAYA: Yeah. Make sure you tell people thank you.

LEVINSON: Yeah. That’s the only message.