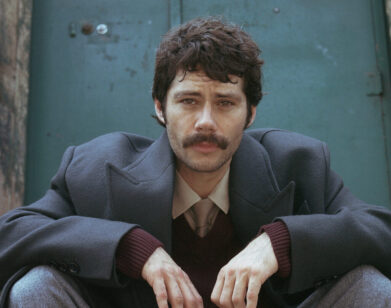

Coming of Age with Ry Russo-Young

ABOVE: RY RUSSO-YOUNG. IMAGE COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES

Director Ry Russo-Young has made a deft impression with her artful, frank, and female-driven films, which probe the experience of the individual and day-to-day realities in depth. “I feel sometimes when we watch movies, sometimes movies tell us how to be, but sometimes movies can tell us how we are,” the director says.

Her latest film, Nobody Walks, is at once a coming-of-age story and a familial chamber drama, a tale of individuals coming to grips with their own flaws and emotional limitations, and how those shortcomings affect their relationships going forward. Olivia Thirlby stars as Martine, a 23-year-old artist who has transitioned from New York to Los Angeles to work on an art film, a primal black-and-white piece featuring a cast of scorpions and other insects. Peter (John Krasinski), a sound engineer, is there to assist her, and Martine takes up in his family’s pool house, along with Peter’s wife, Julie, a former rock-‘n’-roll girlfriend turned therapist (played spectacularly by Rosemarie DeWitt), and her teenage daughter, Kolt (India Ennenga). There is something particularly magnetic about Martine; she possesses a certain free sexuality that affects others, men and women alike, profoundly. Peter and Martine connect in the editing room, and while Martine’s youthful dalliances are merely an unremarkable trait of how she lives her life, her affair with Peter creates rifts in his family that perhaps may never be repaired.

Russo-Young collaborated with friend, filmmaker, and fellow Oberlin alum Lena Dunham on the script, which was refined in conjunction with the Sundance Screenwriters Lab. Along with Russo-Young’s thoughtful direction, Nobody Walks is an intimate, quietly provocative, heart-wrenching film.

Interview last spoke with Russo-Young on the occasion of the release of her second feature, 2009’s You Wont Miss Me. We reconnected last week in New York to discuss creating well-rounded characters, the beauty of process, collaborating with Dunham, and the position of the female artist.

COLLEEN KELSEY: How much of this movie is about the experience of the outsider?

RY RUSSO-YOUNG: I think that’s a piece of it. I think in a way, this is a movie about a lot of things, everything from boundaries to how you navigate being a young woman in the world, to that feeling of being an outsider in a foreign place that you’re not comfortable with, which I think a lot of people feel a lot of times in their life, you know?

KELSEY: You and Lena are both very much New York filmmakers. Why did you decide to shift to LA for Nobody Walks?

RUSSO-YOUNG: I think part of it was a reaction to You Wont Miss Me. My last movie was all about New York and sort of about someone who I saw, Stella Schnabel, playing a New Yorker, and I wanted to do something different. I think the other part of that was just a fascination with Los Angeles as the birthplace of moviemaking and as this counterpart to New York.

KELSEY: How did you and Lena first decide to collaborate on writing this film?

RUSSO-YOUNG: The collaboration with Lena happened really, really naturally. We met and literally that same night, we were like, “Let’s go to the bathroom together!” at a party, and I felt like we had a lot in common. We swapped work, so she saw You Wont Miss Me and I saw her first featurette before Tiny Furniture. Then, it almost seemed to come out of us. I think she liked the idea of writing a movie and then giving it to someone else and not directing it, and I felt extremely lucky to work with someone who is such an amazing writer. I mean, I love the collaborative process. We have a lot of crossover in what we’re interested in, so, let’s make something together.

KELSEY: The last film that you did, You Won’t Miss Me, is an intimate portrait of one woman, and now you’ve transitioned to a portrait of an entire family’s dynamic. Did you want to gain experience with creating more of an ensemble of characters?

RUSSO-YOUNG: Yes. Exactly. I feel like whatever I do last, then I’m like, “Okay! I did that and now I want to do something totally different and challenge myself.” And I think being inside Shelly Brown’s head for a year and a half, it was like, “Okay, I want to get out of this.” I felt like her mind was a K-hole or something, you go down it, it’s this rabbit hole. I really liked the idea of having a bunch of different characters that the audience literally shifts their allegiance to throughout the film and then in some way, there is no one person that you align yourself with at certain moments. You empathize with some characters, and there’s not really a good guy, or a bad guy. We wanted it to be that everyone was sort of human and messes up and makes mistakes, which is the way that life is.

KELSEY: I feel like in a lot of films, if there’s a moralistic lesson to be learned, characters are clearly defined specific to a plot function, i.e. who’s being good and who’s being bad. And what I thought was interesting about this film is that Martine is leading you in as the protagonist, but as the film progresses you can see Julie taking over in her own narrative. Kolt, the same thing.

RUSSO-YOUNG: It’s almost like there’s this hand-off in the movie, in the eyes in which you see the film. You begin to see the family as foreign and then you understand them. As Martine starts to screw up, you want her cast out and as a watcher you’re like, “Yeah, okay!” because you’re protective of this family.

KELSEY: And at the same time you can feel protective of her, too.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Yeah! One of the things I look at in the film is that everybody comes of age despite what age they are. And I think that I have a lot of empathy for Martine. I think that she’s manipulating in the movie but I don’t think that she’s conscious of the level that’s she’s manipulating. I think when you’re young… I don’t think she feels her own power. She doesn’t feel like she has any power.

KELSEY: I think she probably feels as if she’s open to experiencing as many things as possible, and with that mindset, you don’t see the potential after-effects. Or you don’t want to.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Exactly.

KELSEY: What I also thought was interesting—there’s these three female characters. They’re in different stages of their lives, and they’re coming of age in different ways. It could almost be the same woman in different stages of her life.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Mhm-hm. À la The Hours or something? Totally. It’s interesting.

KELSEY: Maybe just in the sense that Julie has reformed her wilder days, as it seems, and Martine’s just entering that.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Exactly. And Kolt’s years behind. It’s sort of unclear of whether she’s going to, how wild she’s going to be. She seems to be a lot more levelheaded than, certainly, Martine. I think that they all do cross over a lot, and the way that there’s a lot of similarity that they have, is the way that they cross over, for sure.

KELSEY: I read that you and Lena were maybe thinking about having a male protagonist for this movie.

RUSSO-YOUNG: We started out again from the You Wont Miss Me beat. I think, she reminded me of this, [I said] “I think we should do a movie about men.” And that’s really where the character of Peter came from. We made him up, and then we made Martine up, in terms of going in and interacting with him, and then she just kind of capsized the movie. [laughs]

KELSEY: And if Martine was a male character, it would be a completely different film.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Totally. It would be a lot less loaded, in some weird way. Or it would be intense, but it wouldn’t have the same sense of judgment, I think, for her. As a young woman who’s doing that, we really tend to [judge]. And also, the other thing is, [the idea of] a female artist. I feel like when people hear the words “female artist” or “female novelist,” half of them roll their eyes.

KELSEY: And at the root of things, the female modifier is problematic.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Yeah, exactly. I think that’s something we were thinking about and working with, is how to do that and do it with integrity, without it being a joke, and why does society view women who are trying to make work like that?

KELSEY: I wanted to talk to you about the film that Martine is making. How much of it is a parallel to what’s going on in the narrative? There’s that one line where she’s talking [to Peter] about community, and one individual coming in… but, of course, it’s told through insects.

RUSSO-YOUNG: Yeah. Well, that’s like a special feature. [laughs] There’s definitely a lot of parallels in terms of the movie within the movie. It’s called Scorpio. I think part of it is the fact that bugs don’t have emotions. They’re not going to be like, “You cheated on me!” and that whole thing. But I also think, there’s what Peter thinks it’s about, which is much more intellectual. There’s the hypothesis of art, which is one thing, and there’s also Martine making it, and she’s so inside of it like a bug and relating to the inner world without almost a conscious outer-critique. But I think that can certainly be applied in a lot of ways, you know? And Peter does apply it in the ways that society’s structured.

KELSEY: The role of sound makes everything so much more intimate between Martine and Peter. Did you initially want to focus on sound as that one aspect of the filmmaking process that brings them together?

RUSSO-YOUNG: Lena and I talked about, should he be an editor, or a sound guy—we discussed where we thought he should land, and ended up on sound, I think partially because we felt like we hadn’t seen it yet in a movie and it felt different and fresh, really. For You Wont Miss Me, I had ADRed a scene, and that process of watching them build the sound up from complete scratch and the actors doing the dialogue again, and the shuffling of the chairs, that was really inspiring for me. It just seemed so under-utilized and it could be made really, really awesome. In a way for me, filmmaking is about following those instincts, what you find really interesting, just having the blind faith that, “I think this is really cool, I hope other people do too!”

KELSEY: It’s fascinating, because you’re seeing all the intimate mechanics of how a film is made that you don’t tend to think about when watching a film. Seeing that process is another layer of engagement. With You Won’t Miss Me you focused on an actress going through the process of getting cast and making a piece of work, here, it’s the process of making a film. Do you feel that your interests, in creating these projects, is reflected in the actual plots of your films?

RUSSO-YOUNG: We’re getting really meta! [laughs] Well, kind of. I’ve always loved movies about making art, in some sense, whether it’s Day for Night, that Truffaut film, or Irma Vep. All of these process-oriented movies I think are really interesting, because I feel like our society is so goal-oriented, so, results. The most interesting part is always the process of how you got there, all the messiness, things that you never want to share. I feel like I figure out, with every movie, more of what I’m doing and studying. I’m learning a lot about the process, so in a way, the things that I’m making definitely reflect the concerns and issues or thoughts that I’m thinking about.

NOBODY WALKS IS OUT TODAY IN LIMITED RELEASE.