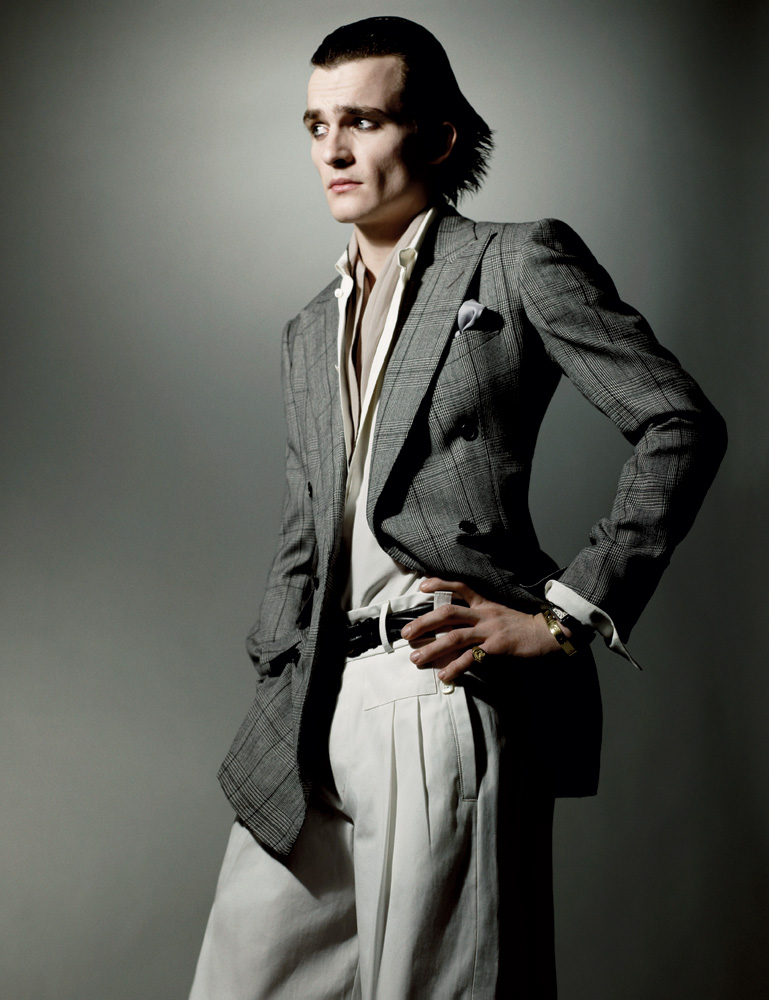

Rupert Friend

The tale of young Rupert Friend begins like many other British coming-of-age stories: in a quaint, almost anachronistic one-horse village in the English countryside. But unlike so many other legends of English lore, Mr. Friend’s journey so far has not involved any kings or warlocks or elves or quests for magical golden rings (though the same cannot be said for tights, which Friend has donned on more than one occasion). His trajectory has been somewhat more earthy: grew up in the county of Oxfordshire in a house with no VCR; became enthralled with the idea of traveling around the world when he saw his first film in a theater, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989); decided it was his destiny to be like Indiana Jones; discovered that Indiana Jones was an archaeologist, and that most archaeologists aren’t as proficient with whips or as prolific in their love lives, which thus makes the profession slightly less appealing; realized, though, that the person playing Indiana Jones, Harrison Ford, is an actor, and he seems to be having a fine time of it; and thusly embarks on a career in the performing arts.

After attending drama school at Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art in London, Friend’s professional acting career got off to a fast start with roles opposite Johnny Depp in Laurence Dunmore’s The Libertine (2004) and his future girlfriend, Keira Knightley, in Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice (2005). But as with every good coming-of-age story, there’s a time when the protagonist must step up and be his own man. That moment appears to have arrived for the 27-year-old Friend. Having recently done duty in the British WWII drama The Boy in the StripedPajamas (2008), Friend stars with Michelle Pfeiffer in Stephen Frears’s upcoming Chéri, based on theColette novel of the same name, and is the male lead in The Young Victoria, a film about the life of Britain’s Queen Victoria, in which he plays Prince Albert to his interviewer here Emily Blunt’s Queen V.

EMILY BLUNT: Tell me about growing up in Oxfordshire. I remember taking a little tour around there and you showed me the corner store where there used to be a girl who you pined for.

RUPERT FRIEND: That wasn’t my village we were in; it was the next village along. But they’re the kind of villages in that area where there’s only one of everything—the boy who bullies you, the shopkeeper who gives you sweets, and the girl you pine for. And then there’s the butcher who does his work by hand with a sword, which was always quite frightening. He didn’t have a fridge either. There were whole carcasses just sitting on a wooden table. It was quite weird. He closed down, and now I know why. But when I was 8 years old, I didn’t know why what he was doing was bad.

EB: You didn’t buy your meat from there, did you?

RF: We didn’t, no. But then the postmistress was also in love with the postman . . . I mean, the village was a little bit like Dylan Thomas and Postman Pat all mixed together. The whole environment was sort of great because there wasn’t any notion of culture or anything contemporary at all.

EB: Now, this childhood bully—did you ever get into fights growing up?

RF: Was I bullied? Um . . . I was fought. I wouldn’t say they were actually fights, because fight implies that there were two people involved, and I don’t think I ever managed to successfully hit back.

EB: So were you not allowed to go to the cinema much as a kid?

RF: We didn’t ever go to the cinema.

EB: Why not?

RF: I don’t know. We didn’t have a video player at home either. I didn’t have a deprived childhood or anything, but watching movies wasn’t something that we did. One of my uncles took me to my first movie in a cinema—Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

EB: Was Harrison Ford your first man-crush?

RF: Indiana Jones more than Harrison Ford himself was—and still is—quite a big man-crush of mine. You know, the guy who’s on the adventure with the hat and the whip and the leather jacket . . . But Harrison is a big man-crush, too. He’s a very cool guy. EB: Were there any other actors who you really looked up to and wanted to be like?

RF: Marlon Brando.

EB: Now, you see, it’s interesting that you say that, because I know that you have a loathing for crowd opinions, but no one will deny that Marlon Brando was like a wild animal amongst the stage performers around in his time . . .

RF: I think that may be a mixed metaphor, what you just said.

EB: Really?

RF: You said he was like a wild animal, and then I think you wanted to say something like, “among the tame cats,” but I think you miffed it.

EB: Rupert, this is what annoys me about you.

RF: [laughs] But, yes, okay. And then on the back of Brando, I would say that Elia Kazan and Tennessee Williams and that period of writing

and directing became a big thing for me. And then Paul Newman and that side of things. And then, in terms of writing, there were people like Dylan Thomas and Jack Kerouac. I did a lot of reading into Kerouac and his contemporaries. I mean, On the Road completely changed the way I looked at what you could do with your life.

EB: Were your parents concerned about you going into this business?

RF: I mean, it’s a pretty risky one. And it’s tough because you probably don’t want your kids to take risks. But then you realize that they like taking them.

EB: I know it’s obnoxious when actors talk about acting, but do you feel like what we do is a worthwhile job? Do you think it’s valuable?

RF: Well, first thing, I wouldn’t call it a job. If it’s a job for you then you’re probably in the wrong profession. It’s like playing dress-up. It’s like make-believe. It’s like you’re suddenly given the key to the doors of these fantastical worlds. And, by the way, you’re going to get paid to do it . . . So I wouldn’t be grumbling about it. It’s more like, “Where do I sign up?” I mean, I’m not intelligent enough to be a doctor, and kind of hands down you can’t argue with the worth of that. But I don’t really have an opinion about the worth of making art. All I would say is that when I’ve been very down, or having kind of a tough time in my life, certain films or pieces of music or books have changed that. They’ve taken me out of a dark place and put me into a more positive one. And I think that if we can do that for people, then it’s certainly worth doing.

EB: So you live in London now. Could you imagine living anywhere else?

RF: Oh, yeah. The one thing I couldn’t imagine is stopping still. I can only go places because I know that I can go away from them, if that makes sense. I like the gypsy lifestyle that filming affords. I like being in different places and finding weird pubs on rivers, like the one you and I found when we were making The Young Victoria. I’ve had some great experiences that have come from this lifestyle—ones that I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

EB: And I don’t necessarily see that as restlessness. I think it has more to do with seeing life in a limitless way, with being alive.

RF: I do, too. I mean, I have a base, but it’s not a geographical one. It’s where certain people are. For me, a base isn’t about bricks and mortar or an

address on a postcard.

EB: You have an eye for detail. When you walked into the room to read for the part of Prince Albert with me for The Young Victoria, I was literally like, “Thank God,” because you have a very natural, quiet dignity about you as an actor. I mean, you understood Albert, didn’t you?

RF: I think so. You’ve got to remember that Albert lives with an empress, and she’s someone who became an empress when she was just a girl. And she’s made one or two mistakes along the way, but she’s ultimately had the strength to continue being that empress, you know, for a fuck of a long time. And I think it takes quite a strong man to say, “My woman will always achieve more than I ever will, she will always have more power than I’ll ever have, and she will probably be more popular than I’ll ever be. And I don’t care.”

EB: Because he loved her.

RF: Yes. And that, to me, is about as close to the definition of a man as I’ve ever gotten.

EB: I know that, in addition to acting, you wrote and produced a short film, but would you ever want to direct?

RF: I don’t know. I think it’s a very hard job to do well. You’re kind of responsible for everyone and everything. There are two qualities that I’ve noticed in good directors: One is that they have their vision very strongly in place; and two is that they listen to everyone’s opinion and still remember their vision. People who don’t listen to anyone else tend to get it wrong, and people who sort of dither between what everyone else says do too. It’s a very hard balance and it can produce some pretty good rows. But that’s what I sort of want as an actor. I don’t want to be a pushover for anyone. I want everyone to row until we all suddenly go, “Oh, yeah, that’s much better.” And not because someone is right, but because we’ve all talked it out.

EB: So, finally, how do you like your steak done?

RF: Rare. Hopping off the plate.

EB: Still pulsing?

RF: Yeah. Bloody, bloody rare.