IN CONVERSATION

Pat Hartley and Lynne Tillman Reflect on James Baldwin’s Centennial

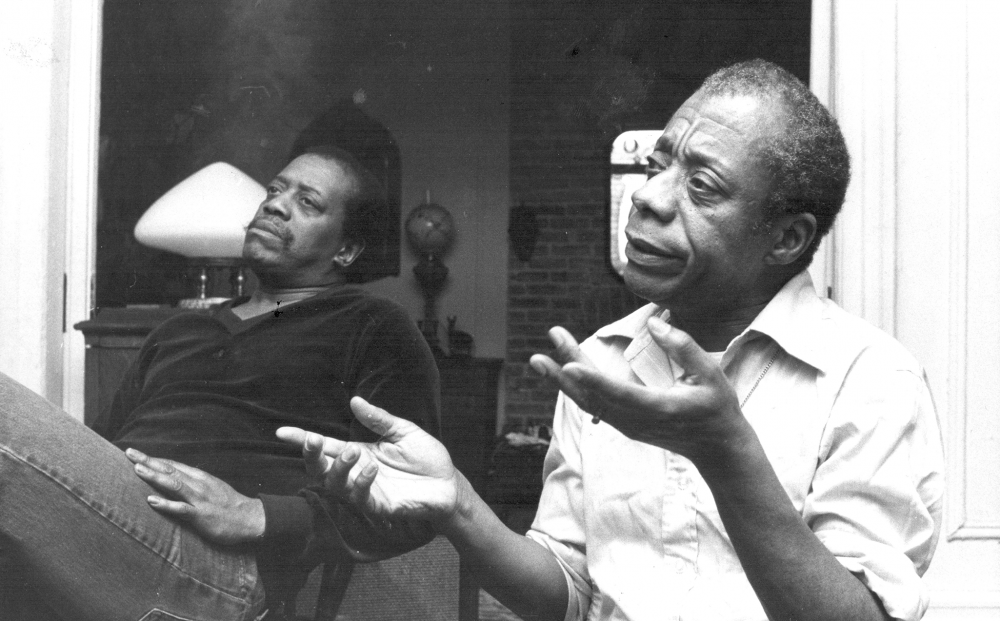

In I Heard it Through the Grapevine, Pat Hartley and Dick Fontaine’s essential 1982 documentary following James Baldwin’s travels through the Deep South some two decades after the civil rights movement, Baldwin figures as a kind of custodian of history, quiet, watchful, and reflective. Though, nominally, the subject of the film, which is showing in a brand new 4k restoration this month at Film Forum, Baldwin frequently cedes the spotlight to activists, intellectuals, and freedom fighters like Amiri Baraka, Sterling A. Brown, Hosea Williams, and Chinua Achebe, with whom he is seen hearkening back to landmark events in the movement, contemplating the courageous efforts of Black Americans to secure the right to vote or the relentless depravity of their combatants. “He wasn’t so much trying to expose what was wrong or what had happened,” the director Pat Hartley told writer and friend Lynne Tillman last week. “He was just trying to listen.” Over the course of their conversation and this film, a different Baldwin emerges: Baldwin as witness, solemnly contemplating the soul of the country at the moment of its agitation. “What struck me was that somebody would tell him a story and he didn’t immediately try to say something,” Tillman told Hartley after seeing the film. “You could tell that he was absorbing it.” Last week, as I Heard it Through the Grapevine returned to theaters on the occasion of Baldwin’s centennial, they got on a call to discuss what it’s like to revisit the film in the present moment.

———

LYNNE TILLMAN: Oh! Hey, Pat. Hello.

PAT HARTLEY: Do you remember how we met?

TILLMAN: I think we had a little contact in the late ’60s, maybe at Max’s [Kansas City] or before. But then we didn’t have contact until I was doing the book with Stephen Shore, which were his Factory photographs. I was searching desperately to find you. I think I interviewed 18 people. At first you weren’t sure if you wanted to talk about that period, but I think I convinced you, or you realized that I wasn’t some slimy journalist, but a writer. And then we became quite friendly. I never met Dick [Fontaine], sadly.

HARTLEY: I remember that you would call and you were very kind. You sent me your book, Absence makes the heart. I read the “Hung Up” story and I thought it was terrific. And then you came to the house and we had a good long talk. I was thinking about what I wanted to say about meeting Baldwin and how it was actually the first time that I was not the subject of something. And I found that interesting. I was a bit at sea about how to do that.

TILLMAN: How did you meet Baldwin?

HARTLEY: I was living in London and there was a producer, Sharon Brant. And the executive producer, Richard Creasey, had been to the South when he was a kid. He went home with a friend and he went South and there was all the segregation, and he remembered that quite vividly. Dick and I were doing a film about the Kennedy assassination, which had been going on for a long time. Jimmy was in London. They’d been talking to him about doing a film, but he was very elusive. He had some bad experiences with being filmed over the years. But when I was talking to him, we started to talk about what kind of legacy we were going to leave. What is it that we’re actually doing? Because he had two lives. He was a novelist and a narrator, and then he also was a historian. I was pregnant at the time, and we discussed what I would leave for my children. So this went on for a while and we came to a conclusion that the Kennedy assassination film, which I’d been working on with Dick for years, was not the story of that time. The story of that time was the civil rights movement. So, when he was a young man, he went down South to do these interviews to bring attention to the civil rights movement. So Dick went to see Richard Creasey, who was the executive producer, and this woman Sharon Brant. And basically I talked him into the story.

TILLMAN: He becomes the vehicle through which you see the Civil Rights movement, and that’s brilliant. The whole film is so unbearably moving. I watched it yesterday on Martin Luther King Day.

HARTLEY: Oh, god!

TILLMAN: And I looked up a quote that Baldwin said about him when he was at the funeral. He said, “I did not want to weep for Martin, tears seemed futile. I may also have been afraid, and I could not have been the only one, that if I began to weep, I would not be able to stop.” And your film is so relevant now because people are asking, and in the Black community, “Is there any change?”

HARTLEY: Mm-hmm. Well, when I was growing up, there was the “Talented Tenth,” and you’re talking about Black people in society and some of them were educated writers. There was Langston Hughes, and then there was Jimmy Baldwin who read every book in the public library. And he had this wonderful teacher and they would go to the movies all the time, so Jimmy and I also bonded around movies. I used to think that everybody needed to be thinking the same thing all the time. The idea with the film was different. He wanted to find out where these people were and what had happened. It was very painful being with him because he was an empath. People would be telling him these stories and they were awful, they were scary. And you could see that he was actually absorbing the feelings of these people.

TILLMAN: What struck me was that somebody would tell him a story and he didn’t immediately try to say something. You could tell that he was absorbing it. It wasn’t his place to say anything. What his place was to hear and to listen and to let their words be what mattered.

HARTLEY: Yeah. And he said, “The people, they’re not telling me the story. I’m listening to the story.” So that was the intent of the film, that we were listening to people who were not also talking directly to us.

TILLMAN: Did anyone not want to speak to him?

HARTLEY: Well, people would come up to him in restaurants and throw things at him and curse at him for being a gay Black man. An evening out with Jimmy was quite frightening in that way. People felt they just could just come up to him and say anything, “Jimmy!” Like, “How dare you?” A lot of it’s to do with him being a homosexual, but other parts of it, doing his other writing, “How could you write about families in the community? How could you do that? That’s a violation.” I thought it was very interesting when he told me that he never was able to write anything in the US. He’d always go to France to write. He could listen here, but he couldn’t write here.

TILLMAN: He could hear what they were saying and it was clear he didn’t have an idea of what they should say, as many interviewers do when waiting for a kind of punch line. It wasn’t like that. As a viewer, what I’m thinking about now is this question of change, and working toward freedom because they’re on the freedom road. And the road has maybe a cul-de-sac now, because you think of the Voting Rights Act now being voted against by these insanely right-wing Republicans in Congress. And I thought, “What would Baldwin think now?” It was hard not to think about that.

HARTLEY: Yes. He was also much more aware of what was actually going on. And there’s a very conservative strain in the African-American community here. So he wasn’t so much trying to expose what was wrong or what had happened, but he was just trying to listen.

TILLMAN: But what he said is so relevant now because he said, “I don’t care if you assassinate me now, but your time, white supremacy, is over,” and this is 1980. And now I’m thinking about how, in this country, that seems what the people who follow Trump are fighting against–the end of their rule as white people.

HARTLEY: Well, the other thing is that there are more poor white people in the country than there are poor Black people. When he talks about the extraordinary makeup job that we’ve organized everything to look a certain way. And the time when he was coming up, this is my take on it, that the Civil Rights movements, all of that was about the morality of the country. It wasn’t about one particular group of people. So, for me, I’m trying not to get distracted by what hasn’t happened. Do you know what I mean? What keeps repeating? And so, part of the civil rights movement was people wanting jobs. They didn’t want to start a revolution. They didn’t want to burn down the factory. No Name in the Street talks about that.

TILLMAN: Wasn’t that part of what Martin Luther King was developing, this idea of jobs and the garbage men’s strike and his wanting to deal with the economic inequity in the country?

HARTLEY: Yes. And Hosea Williams is very clear about that, the structure of what’s actually going on. There’s not even a decent Black restaurant left in all of Atlanta since integration. Nobody was very excited about hearing things like that back in ’82, when the film was screened. Generally, the idea had been settled. You have jobs, but it’s kind of like, when I was a kid, the talented tenth were very visible. That’s what Baldwin wanted to do, he wanted to talk to people that nobody talks to.

TILLMAN: In the beginning of the film, it’s kind of amazing how he begins by opening a book of pictures of the civil rights movement, of Black people being hurt by the police and other really brutal images. And he writes down, “I heard it through the grapevine,” and then it shifts to this club, Mikell’s, which is uptown on the Upper West Side. And then you hear these great jazz musicians who were riffing on Marvin Gaye’s song, “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” And then Baldwin and his brother David are listening so happily and music threads through the film. When Sterling Brown, the professor, says to Baldwin, “You are not a sociologist.” That was an amazing moment. He’s not going to generalize about anyone.

HARTLEY: Absolutely. And the grapevine thing, it came on the radio when we were in Gainesville and of course it’s one of my favorite songs. We were laughing and listening to the radio and that became the theme. I think one of the problems one gets into is trying to get people to agree with you, to understand what you’re saying. But the listening part, you don’t have to have an opinion, you don’t have to do anything. You can just listen.

TILLMAN: Pat, do you know how much of a book Baldwin was able to write on this, did he get started on writing?

HARTLEY: I don’t actually know. That was the intention. And then he became not very well. Then, he was in residence. So there are many tapes and many more interviews that he does with people that are not actually in the film. A very interesting thing happened when we screened it in England. They didn’t realize that they were Black people talking.

TILLMAN: Oh, my god. What was the audience reaction like in the UK? Because this is not their history.

HARTLEY: Well, you know what? It is their history, but they don’t look at it. Apparently American apartheid is different from any other sort of Western nation. So if you have a drop of Black blood, you’re a Black person here in America. The English idea is well, maybe you have a bit of this and a bit of that, and if you’re royalty, then we’ve got a special place for you at the table. I didn’t understand that. I came from the US. So I thought, “Oh, look at all these people of color running around and Jewish people.” And then it took a while to kind of unpick it. I feel like he’s always had to keep his own council in that way. And remember, he was not the flavor of the month for me.

TILLMAN: No, no.

HARTLEY: He was an intellectual but he was an outcast. I mean, going into the Black community with him was almost as dangerous as going to the South, because people were very upset with him. They were upset because he was gay. They were upset because he was an advocate for civil rights. I think the homophobic part has a lot to do with it, but also the idea that there’s only one right way to present the information. One of the things about the film was to not have anybody telling you what it is that you’re looking at.

TILLMAN: Pat, that’s one of the things that makes the film so powerful, because as a viewer, you’re trying to put these different pieces together. As you said, the film is not telling you what to think. You get this sort of beautifully edited patchwork of differences from different people and from their experiences, and Baldwin is the vehicle through which you’re seeing it.

HARTLEY: That wonderful scene where, in the Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner murders, when Jerome takes him down to the bayou and Judy is looking over the edge. “I’m not going down there.” We saw some things that we were unprepared for in that way.

TILLMAN: Oh, I can imagine how shocking so much of it was, how painful.

HARTLEY: And it was an accident that we went to Newark, because he had a speaking engagement. So we had stopped doing everything we were doing and suddenly we’re in Newark.

TILLMAN: The devastation of that city. Was it 1967?

HARTLEY: Mm-hmm. And then we went into the building with this lady. I mean, it looks even worse. And she actually lives there. It was okay when we were looking at empty windows, but we were totally not prepared for that.

TILLMAN: Oh, that was awful. That she couldn’t get the landlord to fix her door. She said, “I have children in here.”

HARTLEY: Yeah. Gainesville and that Newark sequence are really the underbelly of what we’re looking at. The other things are theoretical or explanatory or historical, but riding the whole film is this terrible reality. And his brother David helped a lot with that. David had been the subject of many of his writings.

TILLMAN: Yeah. His brother seemed like a sounding board for Baldwin. Those conversations between them were fascinating.

HARTLEY: And that happened after we had come back home. And then, at the end, we have Ronald Reagan as the president while we were busy documenting things of another era. I saw an opportunity to do this because I was not in the US and I hadn’t really thought of the US as that place. I come from here, that’s what it is. But the opportunity to do this kind of work, I understood what he meant when he said that he could never write anything in the US.

TILLMAN: When I lived in Europe for almost seven years, that’s when I realized I was American.

HARTLEY: Yes, exactly.

TILLMAN: You have all these ideas and you don’t realize how culturally embedded they are, you know?

HARTLEY: Mm-hmm. And also we have these rights. I remember when he talked about voting, the whole idea was that if he was there, the cameras would come to him and then they would photograph the people in line to vote. And he didn’t seem upset by that, but he was just there to attract, to get noticed, to get the people to actually look at it.

TILLMAN: He was the great moral philosopher of the 20th century. I mean, he was so concerned with ethics and it’s in all his work. It’s a magnificent film.

HARTLEY: We’ll talk offline again. Lots to talk about.

TILLMAN: Yes. I’d love to see you soon. Okay. Bye.

HARTLEY: Okay, bye.