South Central’s Forgotten Serial Killer

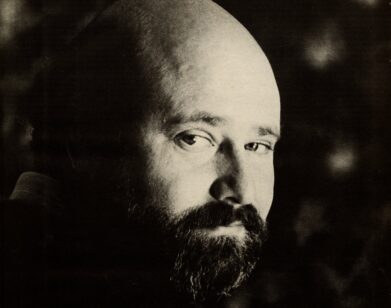

ABOVE: A STILL FROM TALES OF THE GRIM SLEEPER. PHOTO COURTESY OF HBO.

What becomes of a neighborhood when the local police force fails to warn residents about a perverted serial killer plaguing their community? Such is the question posed by Nick Broomfield in his latest documentary, Tales of the Grim Sleeper, which premiered at last year’s Telluride Film Festival. In South Central Los Angeles, Lonnie Franklin allegedly preyed upon vulnerable prostitutes—sexually assaulting the women before shooting or strangling them. Meanwhile, the LAPD, aware of this threat, failed to warn the local residents or devote the proper recourses necessary to catch the murderer. Lonnie Franklin’s rampant killing spree lasted over 20 years.

In his typical self-reflexive style, Broomfield takes to the streets of South Central, a neglected neighborhood of L.A. synonymous with poverty and homicides, to investigate the mysterious case of Lonnie Franklin. Without cooperation from the police, or detectives involved in the case, he relies solely on the testimonies of local residents. The result is a chilling documentary that exposes the institutionalized racism in modern America.

SAVANNAH O’LEARY: First of all, I’m curious as to how you found this story.

NICK BROOMFIELD: I came across these articles that Christine Pelisek had written in the LA Weekly. I’ve spent a lot of time in L.A., it’s always reminded me a bit of Jo’burg, which is a deeply segregated city. And L.A. is really like an apartheid city; white people just don’t go to South Central. It’s just a different world. Very few people graduate from high school, [there is] massive unemployment, incredibly high incarceration rates, incredible obesity, and people die about 20 years younger than the rest of the city. So when I came across the story of 25 years of killing…you could never imagine that ever happening in the white part of the city. Maybe I was more interested, I think, at the beginning, as to how people in the community didn’t know about it either. You know, his friends, and people in the street.

O’LEARY: What was it like, as a foreigner, to earn the cooperation of residents from this predominantly black neighborhood?

BROOMFIELD: I think my white L.A. friends were like, “What kind of backup are you going to take?” We did actually go in with this local comedian called Tiffany Haddish. She’s well known and is kind of sassy and attractive. And so when they started saying, “Back away, what the fuck you doing here? Back away, get the fuck out of here!” All of that, “We’re going to cap your ass!” She tried to quiet them down, which kind of worked a bit. But my initial cameraman got so freaked out that he left. Maybe it was a bit of luck. I’ve done quite a lot of that sort of filming before, so I didn’t really take it terribly seriously. I think they were just protective of their friends and you know, “What are two white guys suddenly doing down there?” But they very quickly quieted down and realized that we were in it for the long haul. I think it was great that we took an office in the neighborhood, very close by. People would always come over right about lunchtime to spend time with us. We’d go out and have a meal and we all got to know each other a lot better. That’s how we got a lot of information.

O’LEARY: Do you think that because they were so reluctant to go to the police with their stories, they were relieved to talk to you?

BROOMFIELD: Yeah, I think it was flattering, in a way, to be asked their point of view. And what amazed me was what great storytellers they were. They know how to tell a good honest story. They were amazing to interview because I didn’t have to prompt them or try and find a way in. They had a story and they just told their story, which is so unusual.

O’LEARY: Pam, especially, is the character that stands out so vividly to me. How did you find her?

BROOMFIELD: We met her about four years in. She would come round to the office and play dice with my son, Barney, and they were all squabbling about who owed who more money. She became kind of a friend and I think she was very amused…Barney is very funny.

O’LEARY: He was your cameraman?

BROOMFIELD: Yeah, he was the cameraman. He wasn’t so involved in the arranging…you know, you spend hours on these films trying to get hold of people and writing emails and making phone calls—he wasn’t very involved in all of that. So he was hanging around a lot more and they would play dice and you could just hear them cackling and laughing in the background.

O’LEARY: That’s such an inversion of traditional roles. Usually the cameraman is just the cameraman, and the director does the communicating.

BROOMFIELD: Yeah. So he established quite a lot of good relationships. He talked to Pam about his girlfriend…they had quite a personal relationship from the beginning. And then we would ride around with Pam and she would just philosophize on life.

O’LEARY: Yeah, she’s so funny.

BROOMFIELD: Isn’t she? We could have done an entire film on Pam, which probably would have been great actually.

O’LEARY: Did you compensate your subjects? Did that ever become a problem?

BROOMFIELD: Well I think it’s a problem if you don’t compensate people that have got no money, because I really feel you’re exploiting them. Right now I’ve managed to get Pam a little job with a production company who are doing an advert down there. She does work as a health visitor—or health worker—but they get nine bucks and hour. So yeah, I do think they should be compensated. Pam was working with us; she was driving around with us. I felt she should get something every day.

O’LEARY: She became a producer.

BROOMFIELD: Yeah. I think if people give you their time and they haven’t got any money then they deserve to get something. Not so that you bribe them to say things that they wouldn’t otherwise say…

O’LEARY: The friends of Lonnie’s who change their minds about his culpability, were they compensated as well?

BROOMFIELD: No, most of them weren’t.

O’LEARY: I was surprised to see so many photos of evidence given how uncooperative the police were. How did you manage to get those?

BROOMFIELD: We managed to get those elsewhere…we got them in other ways…

O’LEARY: Ways that you would prefer not to disclose?

BROOMFIELD: Ways that might not be good to.

O’LEARY: I was bewildered that Chris didn’t have more animosity for his father, given how he was raised and what he was exposed to.

BROOMFIELD: I thought so too. But I think [Lonnie] is Christopher’s best friend, and he taught Christopher to be a mechanic and obviously was a very doting father. I mean, Lonnie denies abusing Christopher in any way. You never really know with these things, do you?

O’LEARY: Do you think he was more disturbed by it then he let on?

BROOMFIELD: I think he’s very disturbed, and also worries that he might have inherited Lonnie’s genetics as well. I think Christopher’s really disturbed, and maybe suffered more than anybody. He obviously loves his father very much and feels very guilty that he was arrested.

O’LEARY: I was curious about the progress of the trial and whether or not this film can be used as evidence. Now that you’ve brought to light the testimonies of all these witnesses that were never consulted, will that affect the trial at all?

BROOMFIELD: I don’t think so, because the DA’s case is entirely based on DNA and ballistics.

O’LEARY: How long do you think it will take until he’s proven guilty?

BROOMFIELD: They keep putting the trial back, so it’s hard to know. There have been so many strange twists and turns with this case. I would think once the trial starts—it’s supposed to start the end of June—it’ll be quite quick.

O’LEARY: And he’ll probably face life imprisonment?

BROOMFIELD: I think the DA will press for death, but it probably will be life imprisonment.

O’LEARY: I was wondering if the people in the film—such as Pam—had seen the film and how they reacted to it?

BROOMFIELD: Well yeah, Pam loved the film. She sort of talked to the screen all the way through. She’s seen it a few times and she came around to a lot of the festivals. She came to New York for the first one. And the last one was True/False. I think at first she was quite intimidated by big audiences and stuff. But by the time we got to True/False…people love her, and she was enjoying it. She’d go out to the street and lots of people would come up to her and she loved it. I think it’s difficult, really, because she’s obviously so bright and so talented, but what does she do now? We’re trying to get her felony convictions expunged so she can get other work, but it’s a really slow process. Every month she struggles to pay her rent. And she can’t depend on the money that we’ve been giving her for any real length of time.

O’LEARY: I’m also curious about Lonnie’s wife, whose presence in the film only lasts a few seconds long. Was there any follow up with her, or any news about her reaction to the film?

BROOMFIELD: I don’t think she’s seen the film.

O’LEARY: Do you think she knows about it?

BROOMFIELD: I’m sure she knows about it, a lot of people from the neighborhood approached her to be in the film. Richard did, and I think Chris asked his mother. They all said that she just didn’t want anything to do with it, and that we should respect that, which we did. They’ve sold the house now. Christopher’s moved out of Los Angeles to another city…trying to start his life again. I don’t know where she is. I would imagine she’s still in L.A. because she’s still got her job.

O’LEARY: At the end of the film, when Pam says, “there’s another [killer] out there,” what did you mean to imply with a closing statement like that?

BROOMFIELD: Because nothing has changed politically, or in terms of the police, or the attitude of the rest of the city towards South Central, it think the same situation will basically occur. I think she’s talking about the system…that’s how I always saw it.

O’LEARY: How different is the final film from what you originally envisioned?

BROOMFIELD: I probably expected to get a lot more from the police, and a lot more forensics stuff, and probably much less from the community and the friends and the victims. To a certain extent a film is obviously defined by what you can get and what you can’t get. I always feel the exciting thing about documentaries is that it’s spontaneous and raw. You know so many documentaries now are very carefully scripted before you start, and then people are sort of put in chairs which are beautifully lit, and they tell their stories and you do that with another 10 people and you then construct a story from what they say. You do a sort of paper thing, and then you put some images in-between, and that’s your film. And that’s so not what I think is a good documentary. It can be so much more than that, it should be much more of an adventure and much more uncertain…like real things are.

TALES OF THE GRIM SLEEPER IS AVAILABLE NOW VIA HBO.