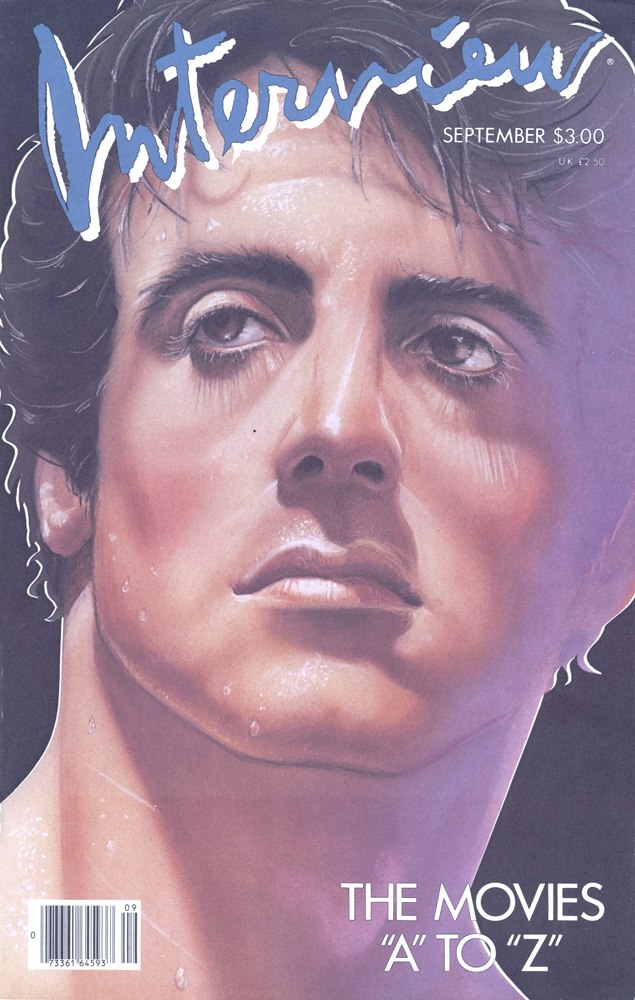

New Again: Sylvester Stallone

Creed shouldn’t be good. It’s a reboot of Rocky, the feel-good, boxing franchise that spanned the 1970s and 80s. No one was particularly mournful when Sylvester Stallone hung up his gloves after Rocky V in 1990, and while the first few films were very successful and remain iconic, they feel extremely dated—rooted in long-faded Cold War climate. But Creed is good—excellent, even. In aspiring boxer Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan), second-time writer-director Ryan Coogler (Fruitvale Station) has created a protagonist that feels vulnerable and modern. He can stand on his own, but if you are familiar with the original films, it will heighten your affection towards him.

In addition to Creed, Fox announced earlier this week that there will be a television reboot of Rambo, another Stallone favorite. Though the details are still being decided, Stallone has already singed on as Executive Producer and the series will be called Rambo: New Blood, focusing on John Rambo and his son J.R., who did not appear in any of the four original films.

Here, we’ve reprinted our cover interview with Sylvester Stallone from 1985, the year Rocky IV was released and Apollo Creed, Adonis’ father, met his demise.

Sylvester Stallone

By Pat Hackett

He’s a man with myth to spare. For the time being he’s shed the custom-made jungle-running rags of his alter ego, John Rambo, and he’s back in the red, white, and blue boxing trunks of his resplendent original, his alter ego Rocky Balboa. Sylvester Stallone and the crew of Rocky IV mill around the middle of a boxing ring on the MGM lot in Los Angeles. Soundstage 12 has been turned into an arena, Sovietized with posters of Marx and Lenin hanging overheard, staring down formidably to motivate their Great Red Hope, the 245-pound Dolph (formerly Hans) Lundgren, who plays the biochemically-engineered Russian fighting machine Rocky will duke it out with in the film. I’m stationed in a corner of the ring feeling a little like a trainer, only able to get his two cents in between rounds, putting questions to Stallone when he has a few moments between shots.

PAT HACKETT: As we talk, passengers from TWA flight 847 are being held hostage in Lebanon. If you had loved ones on that flight, who would you want to go get them—Rambo, Dirty Harry, or Jesse Jackson?

SYLVESTER STALLONE: [laughs] No doubt in my mind. Have to go with my closet kind.

HACKETT: Really? You don’t think Rambo would get them killed immediately?

STALLONE: Well, it’s a calculated risk you have to take because you consider the kind of credibility the country is losing and we have to establish right now a fundamental guideline of absolute—

HACKETT: But we’re talking about your dearly beloveds, and they’re hostages! And remember that the Delta Force has only pulled off, I believe, one successful hijack rescue operation—that airport thing in Venezuela last year—and remember the mess that happened on their Iran mission…

STALLONE: But you’re forgetting something.

HACKETT: What?

STALLONE: Rambo! [laughs] See, when you say the name, “Rambo” to me, I have a vested interest. But no, I would like to see negotiations get the hostages back safely. But once I got them back, it would be a whole new ballgame—someone would have to atone. There has to be a consistent and forceful reaction from the American government. Punitively.

HACKETT: So I guess you’re saying to send in, say, Jesse Jackson to negotiate, then Rambo to retaliate?

STALLONE: [laughs] Hey, send Rambo to negotiate! Let me get this shot. I want… [walking towards the set] I want some military in there—something that says RUSSIA! Russian faces. Lots of strong Russian faces…

[Stallone checks the set-up and then calls for action, giving directions to the cameraman as he watches what’s being photographed on one of several television monitors set up around the ring.]

HACKETT: Directing seems pretty effortless for you. How much easier is it now than it was during Paradise Alley and Rocky II, your first two directing efforts? Because when I saw Rocky III it seemed like you’d learned so much since doing Rocky II. How did that happen?

STALLONE: I’ll give you a scoop on that, okay? I did not want to direct Rocky II. And if you notice, Paradise Alley had been a vastly different film, directorially, than Rocky II. To me, Paradise Alley was much better—a little more free-formish, a lot of lap dissolves, a lot of freeze frames, overlays. But then when it came time to direct Rocky II, I decided to try to stay consistent to [Rocky director John G.] Avildsen’s original style. You know, John was pretty straight-ahead. So Rocky II, I did very literal—I didn’t do any of the stuff I liked to do. See, I love trick shots, I love subjective camera a great deal. I love being so tight on people in close-ups that the veins in their eyes look like the Mississippi River. I love montage. I think that, visually, people get bored quickly. I like them to think, “What’s that?” and by the time they see it, it’s gone. [smiles] A little legerdemain…

HACKETT: In what style are you directing Rocky IV?

STALLONE: Subjective as hell. Everything is through Rocky’s eyes. What we’re shooting now, this all takes place in maybe just two seconds of the movie. But it’s enough to establish his dilemma—he’s been punched and he is in unbelievable pain, trying to regain his composure while undergoing the close proximity of embarrassment. By that I mean that boxing is the only sport where you have the audience coming right up to you and saying, “You Stink.” And you got to deal with that. It’s like being in front of the lions.

HACKETT: What about your boxing promotion business? Is that history?

STALLONE: It’s… It’s becoming history. I still have a few outstanding ties with boxing, but I felt that it really wasn’t rewarding for the amount of time. You have to be a full-time promoter to really… [looking towards the set] That’s nice! You gotta Dutch it, guys. It can’t be straight on… Can you get it tighter?… Great! This is so schizophrenic.

HACKETT: Last year there was a news item on television that you’d told some Italian magazine—maybe L’Uomo Vogue—that you intended to be the “first Italian-American president” and the “second actor president.”

STALLONE: Never. I would never run for president. Oh jeez—First of all, I haven’t talked to L’Uomo since 1977 and—

HACKETT: As I said, I’m not certain which magazine they attributed it to.

STALLONE: I swear to God. Never. Never. I’ve heard a few of these things in the past and they’re just so far out. Some people have skeletons in their closets, but I have a graveyard.

HACKETT: If you wouldn’t run for president, would Rocky?

STALLONE: No, Rocky would definitely run for councilman. Maybe mayor. But these people are actually most effective in the family unit. That’s where they shine.

HACKETT: As Rambo, you’re down to mostly body language, you say practically nothing, whereas in your early films like Lords of Flatbush, where you wrote a lot of your own dialogue, and then in Rocky, where you wrote it all, you were full of good wisecracks. Since you’re a natural at the parrying style, I wonder if it requires a lot of self-control to play these non-verbal parts now? Or maybe you’ve just changed.

STALLONE: You know, I do a great deal of writing, yet I’m usually taken for a non-intellectual, a person of limited intelligence. I don’t know why, but I figure it’s because physically I don’t look intelligent. I don’t fall into the physical manifestation of a man of letters. So I guess people assume the scripts are delivered to me under the door.

HACKETT: Not many people know that you went by the name “Mike Stallone” until you were 27. You do look like a Mike. Was it your middle name?

STALLONE: No. It was just that growing up “Sylvester” was a real task. Tweety-birds…A real task. And I just wanted to-blend in. I didn’t want to cause waves. I went to 12 or 13 different schools, and I wanted to just sound neutral. When I went in as “Sylvester,” right away it was going against me.

HACKETT: But had you thought then of calling yourself “Sly”? Sly’s a great name.

STALLONE: No, see, “Sly” in the ’50s would’ve been like calling yourself “Rocky.” Those were the days of Peter and John and Christopher.

HACKETT: But did Sly and the Family Stone maybe give you the idea?

STALLONE: Yeah, it did. He broke the ice and I decided to go with it.

HACKETT: When did you start writing? Did you do any in high school?

STALLONE: It was one of the assets of failure. If I’d succeeded right away at acting I wouldn’t have sought out writing. And eventually writing became more interesting to me than acting. You see, success is usually the culmination of controlling failure. Through failure, I found different ways to reverse my problems and get into the mainstream of Hollywood. If I’d made it right away as an actor, I would’ve stopped at a certain level and stayed there, probably as a character actor. I don’t think I would’ve made it the way I’ve made it now. And I wouldn’t have changed myself physically and I would’ve stayed kind of heavy and I would’ve—

HACKETT: I liked you heavy.

STALLONE: You liked me heavy?

HACKETT: The early part of F.I.S.T. was your cutest look. Full in the face.

STALLONE: My girlfriend said the same thing, so I wonder what am I killing myself for. Wait a minute. [to the set] There’s a problem with the dry ice? Just give me smoke, then.

HACKETT: What do you say to people who say that your movies are clichés filled with clichés?

STALLONE: Clichés are what good writing is all about. Because our lives are basically clichés. We follow a certain pattern, a maze, if you will, every day, tracing our steps into certain districts and neighborhoods and back home. So it’s easy for people to relate to clichés. That’s why comedy routines are based on mutual experiences of clichés. You go, “Oh yeah! That happened to me, too! Yeah, yeah, yeah…” And I think that’s important in film. You get the cliché going, and then you alter it. But you’ve got to establish a certain relatability from the beginning, otherwise, it’s too “far out.” It’s like Rocky. Rocky is a very predictable movie. The ending is a foregone conclusion. But, in the middle we get a little but of a twist. We don’t stray too far, though, because then I might as well have Rocky enter a space capsule and I’d enter a whole different dimension in filmmaking.

HACKETT: How many more Rockys do you envision?

STALLONE: Oh, this is it for Rocky. Because I don’t know where you go after you battle Russia. You know what I mean? You have that clash of ideologies and you take on supposedly the greatest fighting machine ever built—a biochemically produced Soviet fighter. Where do you go after that? Everything subsequent is anticlimactic. And I don’t think I can do any better. If I can go out with four good Rocky films, I’ve been extremely lucky.

HACKETT: Do people come up to you all the time and say, “I have an idea for your next Rocky?”

STALLONE: Uhhh yeah. And then you know what? You listen to ‘em and then an hour later their lawyer calls and sues ya.

HACKETT: So what do you say to them? Are you polite?

STALLONE: I just rush off, I say, “Got the story, got the story already, thank you very much, got the story.” But with writing, I think you have to be honest with yourself. I have a certain kind of writing; that is, I like to really embellish the human spirit. You have to write about something you have a feel for. also, you have to have an ideal sense of dialogue and timing. I try to eliminate as much dialogue as possible, and I guess Rambo is my really best experiment with how to eliminate dialogue. Every word that he says in there really has impact. To me, the most perfect screenplay ever written will be one word, when you finally reduce it down to that. Until then, writing will be an imperfect form of communication.

HACKETT: Let’s talk about the last line Rambo says in the movie—the line that all the reviewers cite where Rambo’s asked what he really wants and he says something like, “I want what every other guy who came over here and spilled his guts wants—for our country to love us as much as we loved it.” You once said you always deliver three different versions of a line during filming: a low-energy version, a medium one, and a high, so that later in the editing process the director can take his pick. Do you still do that?

STALLONE: Yeah. And the last line in Rambo was the version done at a high level of energy. Almost the highest. I did seven versions of that line. I went from sobbing like a baby—absolutely whimpering—

HACKETT: How’d you get the tears going?

STALLONE: They just came. Sometimes when I don’t want to cry, I cry. And when I want to I can’t. It’s subconscious. Like sexual performance. When you think, “Ahhh, tonight’s the night…” Well… But then when you think, “Just let me get home and get right to sleep,” it winds up you’re swinging from the rafters. It’s just really interesting how perverse the subconscious is. Really, I wish I could master that. So I did the line at about seven different speeds and I knew that if that line didn’t hit home at the right temperature, that the whole film was going to be lukewarm. And I hope that it worked.

HACKETT: Did you change the words, too? Say things like, “What the hell do you think I want?”

STALLONE: Exactly. Played with the words, and on the heavier versions I said, ‘The men who came over here, spilled their guts, gave everything they had—” You know, really drove it all home, the sacrifice part. And that’s what I feel, too. I think people of all occupations, whether it’s the camera—puller or the man who’s doing the catering, they can identify with Rambo’s frustrations, with the veteran’s frustrations. At the very end, the one person who Rambo should kill, he doesn’t kill. He lets it live. Because you can’t kill that kind of hypocritical bureaucracy. It goes on forever.

HACKETT: I’m sure that you must know a lot more about the prisoners of war and missing in action than you showed in the movie. Give me a percentage on how realistic you think Rambo is. One percent? 10? 90?

STALLONE: All the facts, all the words spoke, are documented and true. It’s about the POW’s not being returned because of the war reparations that the North Vietnamese wanted and…

[Stallone is asked what kind of camera setup he has planned for a close-up shot of the huge Russian fighter, Dolph, as he takes a stunning punch at Rocky. Stallone inquires what would happen if they shot into a mirror so that the image could bounce back and he’s told, essentially, that this wouldn’t make any difference, that the film wouldn’t see it.]

HACKETT: Your boxing really seemed to improve a lot from Rocky II to Rocky III.

STALLONE: I’ve always boxed a certain way. But with Rocky, the character himself had to be kind of awkward. So I had to learn to fight that way, but the way I was in Rocky III is more like the way I really box.

HACKETT: What is your weight class?

STALLONE: Light heavyweight/heavyweight.

HACKETT: What did you think of the Hagler-Hearns fight?

STALLONE: Excellent. Matter of fact, after I saw that fight I went back and re-choreographed the first round in Rocky IV and just let caution to the wind. We were really slugging it out for the first 30 seconds. I wanted two people like in everyday life. You know, when you think you have it all together and then you’re presented with a very menacing situation in which your ego goes totally out of control and you just go for it. By that I mean you lose all sense of style, proportion, and distance, and you just revert to animal savage instinct. Which is adlibbing. At that moment you don’t care about poise—you’re fighting for your life.

HACKETT: And how did you like the McGuigan-Pedroza fight?

STALLONE: I saw that kid a long time ago—McGuigan—and he had a white light around him. He was special. Gifted. Born to do that. A freak of nature. A featherweight with the hands of a lightweight and the reach of a middleweight. He has a strength that far surpasses his body structure. You know, he was born, he wasn’t manufactured. Most fighters who fail—and in fact, most people who fail at anything in life—were not really cut out to be in that situation. But this kid was born to do that, and therefore it was an inevitability. And the fighter he beat was a great, great champion. So there you have that rare situation where the crown was abdicated to a really superior fighter by a superior fighter. Great.

HACKETT: Who’s the best fighter you’ve ever seen? Or perhaps just your favorite for some specific reason?

STALLONE: Well, of course, Muhammad Ali was just incredible. And Marciano I found to be an unbelievable soul who was always working from the decent position…I think Hagler has really proved himself…and Holmes. He’s a superior fighter, really excellent.

HACKETT: With the way myth and reality blur in the American consciousness, aren’t people going to look back some day and think: “Rocky? Oh yeah, he’s the one who beat Muhammad Ali?”

STALLONE: I’ll set them straight.

HACKETT: What fighters have you liked on the screen, who you thought were actually good boxers?

STALLONE: Errol Flynn had an excellent left jab… Robert Ryan in The Set-Up was very good at inside counter-punching because he actually had been a college fighter… and John Voight’s technique [in The Champ] was very good. And I was even impressed with Erika Estrada’s movements, although the film [Honeyboy] wasn’t that good, he seemed to be pretty good at it.

HACKETT: I like all these Soviet propaganda posters that you’ve got hanging all around.

STALLONE: Thank you, thank you. You should’ve seen the original arena we had in Vancouver where we shot most of this. This is jus the mock-up. Up there it was extraordinary. They had a banner of the Russian fighter that was the size of a football field. Fantastic.

HACKETT: Have you ever been to the Soviet Union?

STALLONE: No. I tried to get in when I was over in Budapest for 20 weeks doing Escape to Victory. But they wouldn’t give me clearance. I guess because of the Rocky films.

HACKETT: You mean because they were so all-American?

STALLONE: Mm-hmm. It’s propaganda there from the time you brush your teeth till the time you—brush ’em again.

HACKETT: Have you met President Reagan?

STALLONE: Oh, sure.

HACKETT: Would you call yourself a Republican?

STALLONE: I vacillate. I really do go with the man. I do believe that American should deal from strength, that talk is a poor substitute for action.

HACKETT: Yeah, but when you look at Reagan trying to deal with this hostage situation and he’s talking tough—it’s just all the more embarrassing because there’s nothing he can do, either.

STALLONE: But you have to go back 20 years before this and figure out why we’ve wound up in this position. It’s simply because we’ve been too diplomatic. I feel that America is like a child that grew up so strong and so fast and so tall that it became self-conscious about its size and started to stoop over so as not to offend anyone.

HACKETT: Did the “stooping over” start with Vietnam?

STALLONE: Before that. Korea. You see, we were trying to do something very admirable, which was to take an intellectual approach to world problems. And it was a well-worthwhile experience. But, there is an age-old proverb that really does hold true in every area of life—in relations between nations and right down to the most subtle and sophisticated or must unstable and unsophisticated relations between lovers—and it is this: they took “kindness” for “weakness.” Period.

HACKETT: But the intellectualizing started because the nuclear bomb gave new meaning to “strength.” Even a man like General MacArthur, during the Korean War, at one point advocated dropping the bomb. But then later on I think he admitted that it hadn’t been such a good idea.

STALLONE: Yeah, I know. It’s where do you start with a clean canvas? It’s a real mess. It’s like trying to paint over somebody else’s work. There’s a lot of old residue that seeps through. And that’s the difficult thing about any presidency. It’s almost hard to hold anyone accountable, because it takes at least 10 years to work through our system to have any profound change, don’t you think?

HACKETT: What other presidents have you met?

STALLONE: Ford, Carter.

HACKETT: I saw in the papers that you just met Governor Cuomo of New York, and some people think he may be a future president.

STALLONE: Yeah, I did meet him recently. He’s nice, isn’t he? You think he has a chance?

HACKETT: He was quoted as saying you were “very, very bright” and you had a “deep, subtle mind.” Would you ever endorse a political candidate if you liked him? Go out and stump?

STALLONE: If he really needed it, sure. I would step up. But I don’t tend to think I could swing that much weight in either direction.

HACKETT: Uuuhhh…

STALLONE: Well, maybe I’m being naïve. But, for instance, with Reagan, I could see he was doing [laughs] so well, that me stepping up would only be like adding a spoon of sugar to a cup of coffee that already had 10.

HACKETT: What do you think the United States’ policy toward Central America should be?

STALLONE: When crossing someone’s borders you have to be prepared to engage in a war that is far more brutal than if it were to take place on neutral territory. It’s kind of like the, uh, whatdaya call it? Like the Homestead Prerogative.

HACKETT: What’s that?

STALLONE: If you come into my house, I’m going to fight much more viciously to get you out than if we were on a neutral piece of land. So I’m saying that America, if we’re going to go into Nicaragua, we ought to be prepared to go all the way and not just marginally. Because otherwise we’re going to be constantly harassed and eventually humiliated. Again.

HACKETT: When the Vietnam War was going on, how were you thinking? And now in retrospect, what do you think?

STALLONE: The same thing. First of all, since they committed to that war, which was rashly—and I use that word too lightly—entered into by Kennedy, once they were committed, the only way to fight a war of that nature is by the air. You can’t put ground troops on there until you’ve completely, shall we say, “tilled the soil”…I’m seriously. You have to say to the country, “Look, if we don’t settle this in the next week, it’s gonna be all-out, no hold barred.” I think that’s the way it’s gotta run, make a settlement, or he’s gonna strike. I don’t believe in the sneak attack. I think that if you have the power like the United States, if you’re going to talk tall and carry a big stick, eventually you’ve got to use it or they’ll think you’re bluffing. And the men in Vietnam weren’t allowed to fight the war with any kind of concern to win by the government. It was like a war of attrition.

HACKETT: Did you feel all this at the time, though?

STALLONE: Oh, absolutely. When I was cognizant of the war, I was very angry at the street-corner liberals who were trying to defame the footsoldier. Because there was a man who had no choice. He was a cog in the wheel, just trying to survive. I was always aware of that. What I was angry with was the government being so indecisive. Was this an economic war? Was it a war to try to get out “gracefully”? What was it? Plus, they were fighting the war under a microscope and I think our country was very self-conscious about maintaining an image. But how do you maintain an “image” during a war?

HACKETT: Did you express these viewpoints to anyone at the time?

STALLONE: Yeah, I did. As a matter of fact, I wrote an essay when I was a sophomore in college.

HACKETT: Since you’re now probably the most famous Vietnam War “veteran,” how did the draft avoid you?

STALLONE: I didn’t pass the physical, actually. Something with my ears.

HACKETT: Were you disappointed?

STALLONE: As a matter of fact, yes. I tried twice. I went back and was rejected again.

HACKETT: we were talking before about the POWs and about how “real” you thought Rambo was. A lot of reviewers made a point of saying that they thought the premise of Rambo was incredible. However, I disagree—I loved the premise, found it completely credible, but the details were unrealistic. And I’m not just talking about all the firefight fantasy; I mean basic things like that the Vietnamese would’ve moved their camp immediately, as soon as Rambo extracted that first guy. They wouldn’t just sit there waiting for the U.S.A. to come back. And what really bothered me most was the cavalier way the POWs’ identities were treated; Rambo never even asks their names, the most important thing to do on a POW mission.

STALLONE: Right, right. But it was the spirit in which it was done. It was the intention rather than the actual mechanics of it. Because after all, no one knows exactly how the enemy is going to react, whether they would be foolish and not think to move them, or whatever. It’s all speculation. No one knows for sure. So when someone says, “That’s ridiculous, that’s heightened comedy,” and everything else, that’s not fair, because you don’t know. Could Rambo live through all that? The odds on it? Most definitely not. But people have lived through some very bizarre things. and I’m not saying that it could or couldn’t be done. What we’ve done is purely a dramatic effect which was to arouse the audience to a sense of understanding and pride in their country. Whereas many other films have taken a different track, we wanted to go almost jingoistic. And I think we were really obvious about doing that.

HACKETT: What have you learned about lighting yourself? And about film lighting in general? Because Vincent Canby in The New York Times made a very funny comment about how you looked in Rambo. He said the camera “caresses Mr. Stallone’s face and body with an abandon not seen on the screen since Josef von Sternberg made movies with Marlene Dietrich.” Did you catch that one?

STALLONE: Uhhh… [laughs] See, I’ve never brought in a “specialist” in lighting. Uh, I just want to establish right on the tone of the scene, so if it’s a dark scene and I’m trying to focus in on the central character, I won’t have a lot of ambient light in the room. Which is more effective: to walk into a ballroom where all the lights are up, or to dramatically enter a dark ballroom and throw a “sheering” white spotlight into the actor’s face? Ba-boom. In the boxing ring here, those two men are equal, so we go with overhead lighting. And in Rambo I was trying to show the brooding, frightening effects of lighting. Lighting can bring out certain contours in the body, in the face, in the eyes, that otherwise flat lighting couldn’t. And I mean, if the torture scene had taken place in a white, formica, fluorescent-tubed kitchen of a mobile home it wouldn’t have been quite as dramatic, would it?

HACKETT: Now that your old friend John Travolta, who you directed in Staying Alive, is going to be directing this summer himself, a movie called Greenwich—

STALLONE: Is he really?

HACKETT: Well, that’s what he’s been saying in all his interviews. Has he asked you for advice?

STALLONE: I haven’t seen John in about five months. But I’ll see him at my birthday party in a couple of weeks. I really like John. But he [laughs] hasn’t asked for anything yet. Not yet. And I think he’s better off that way. Because often people going into directing want to learn as much as they possibly can about “technique.” And I say the hell with that. I think there’s something about being a neophyte that’s refreshing and hard to duplicate; it brings about real innovation. Innovation usually comes about through blind ignorance. You say, “Oh my God, I don’t know what I’m doing, so let me try something weird…”

HACKETT: You mean like a little while ago here when you asked one of the men, “What would happen if we shoot it off a mirror?”

STALLONE: That’s exactly what I’m talking about. And they told me it wouldn’t make any difference. But [politely lowers voice] I don’t know that they’re right, and I’ll tell you something… I am going to shoot it off a mirror.

HACKETT: Really?

STALLONE: Absolutely. I’m going to try to something strange. You take a piece of Plexiglas, and a glove full of blood, right? He’s behind the Plexiglas and he’s going to punch into the glass. It’s supposed to be “me.” And I want to reflect my face onto the glass so it looks like he’s hitting me and it’s splattering. But! It might be interesting if he hits the Plexiglas, and I have a reflection of him in the glass so he’s hitting himself, in a sense. You know what I mean? I don’t know if it’s going to work, but it might be an effect.

HACKETT: I’ve never heard you mention any of the old-time directors. Are there any that you really admire? Do you regret not working in the old days with one of the greats like, say, John Ford directing you in something?

STALLONE: No, not really. I think the directors today, their skills are more honed. A little more—I hate to use the word “hip,” but…innovative. John Ford was great, but I mean, John Ford today…To hold on a master shot for… See, the audience today wouldn’t accept it, I don’t believe. Because in the age of quick cutting, of dramatic close-ups, of rack focuses… Like that great director Abel Gance who directed Napoleon, for him to hold on those shots of 5,000 men running for 15 minutes, it can’t be like that today.

HACKETT: That brings us to the move you’re going to make about Edgar Allan Poe. Years ago, before you wrote the first Rocky, even, you wrote a script about Poe. Now, finally, you’re going to make it, direct it, and star in it, of course. And I hear you’ll be using special effects…

STALLONE: Got to.

HACKETT: In an interview about two years ago, you said that “Everybody’s going to die someday—even Rocky’s going to die—but that doesn’t mean you have to see it.” You were referring to how you planned to end Poe with him triumphantly giving a poetry reading, rather than with his death. But now I hear you’ve changed the ending.

STALLONE: No, no. Still the same.

HACKETT: But I heard the special effects were going to be used in a death scene for Poe.

STALLONE: Yes, that’s right. He will die. But just as his death is at its total culmination, I’m going to dissolve into a portion of the film 10 years earlier when he was at his height that we only saw the first part of. For example, I’ll have him come out and recite a poem, “once upon a midnight dreary / while I ponder weak and weary” and then dissolve out. Right? We never see him complete the poem, right?

HACKETT: Yeah…

STALLONE: And so then we get to his death and we go back and pick up at that point where we left off. It’s like cutting away from a guy who’s ready to hit a baseball, and at the end we come back to him connecting. You pick up that hit and you think, “Ohhh, that’s what that was about.” So the film goes out on an “up” ending. Even thought the film is a downer, the mind shifts gears so quickly, you’re back in another, happier time. we’re very forgiving. Our emotions change like that! So you throw cold water on people and they get out of their unhappy state. It’s great the way the old-time directors used to manipulate the hell out of you. You see someone dying and all of a sudden a ghost would come out and they go walking hand in hand up the stairway.

HACKETT: What contemporary movies have you seen recently that you’ve liked?

STALLONE: I really admire the dedication that goes into something like The Killing Fields. But what I really admire more than anything else is technique. Say, in Blade Runner, or the camera work in Excalibur. The special attention to details, which I realize requires such incredible patience. Most of the films I myself like don’t do very well. Every director, he has a choice, whether to go for subtlety and try to articulate every minute detail, or to go for the broad strokes and hope that the people will fill in between the lines. I tend to go for the broader strokes.

HACKETT: I want to read you something that Clint Eastwood said in an interview recently, and see how you feel about it: “There’s no real excuse for being successful enough as an actor to do what you want and then selling out. You do it pure. You don’t try to adapt it, make it commercial.” He was talking about his small film Bronco Billy and apparently his philosophy is that yes, you make money and do big, audience-pleasing commercial movies, but then you also do other smaller movies that aren’t necessarily commercial, and in those you ought to go for realism.

STALLONE: Yeah…

HACKETT: So I’m thinking, you’ve made fortunes on all the Rockys and Rambos, and so on your Edgar Allan Poe project, don’t you ever just think, why bother to try to make it commercial? Why not make it as all-out depressing and morbid as his life probably was anyway? I mean, why even attempt to be upbeat about a man so obsessed with death?

STALLONE: Right. Well, no one’s life is totally morbid. Even on a subtle scale there’s little flashes of enlightenment and of happiness and joy. And what I try to do is really mix it up and deal half in his conscious mind and half in his subconscious. I think that will bring the audience into his world to stage traumas that’re taking place inside the writer’s mind, like his stories.

HACKETT: What is the biggest success you can envision for the Poe movie? Do you imagine that people would accept it at the level they accept Rocky or Rambo?

STALLONE: Never. No. Maybe 10 percent. There’s no doubt about it. One is contemporary and relatable. The other is almost a history lesson.

HACKETT: I wonder if you’ve ever found anything so horrible that even you can’t make it upbeat?

STALLONE: Oh, yeah. I was going to do a child abuse story a while back. And also right before One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest I was going to deal with life inside a sanitarium. And those things are very hard to make funny. Even though you can do it brilliantly like they did in Cuckoo’s Nest where you blend it all together.

HACKETT: I know that for Rambo you ate a lot of protein and that for F.I.S.T., to get your weight up, you ate a lot of bananas. Is it safe to say that one major way you get into characters is by simulating their physical characteristics through diet and exercise?

STALLONE: Yeah, no doubt about it, it’s—

HACKETT: So what do you think Edgar Allan Poe ate?

STALLONE: He was a poor man. Grains. Cornmeal. Very few vegetables. And if there were vegetables, I’d say they were of the root variety. Tubers. Rutabagas, potatoes, maybe a carrot now and then. No fish for sure. Maybe meat that had been smoke-housed, but meat very rarely. Of course, all the inexpensive foods he would live on—the grains and carbohydrates—are what is very good for mental abilities.

HACKETT: Are you going to start eating that way when you play him? Become an alcoholic and everything?

STALLONE: [laughs] A little bit, yeah, but if I go too far on it, me, I just get so thin that I’ll waste away. I’m basically a thin person.

HACKETT: How’d you get so far in Lords of Flatbush?

STALLONE: I was never without a pint of ice cream in my hand and another one hidden away in a thermal bag tucked inside my motorcycle jacket. I was constantly eating to get that look. Unbelievable.

HACKETT: When I watched you on the Today Show last month, you said, quote, “I would like to do a really grand period piece in the religious genre. Something that has a great weight to it. I really wan tot deal with spirituality.” Having noticed how much you use the Christ image in your movies, and remembering that in your first pre-Rocky Interview interview in January 1976 you said you actually liked to be persecuted. I wonder if this religious movie you want to make will involve your playing Jesus Christ…

STALLONE: No, no, no. Certainly the image of Christ is the strongest image in post-Christ society. It’s the number one icon…symbol of humanity, of brotherhood, of love. And I think you can’t tamper with that. You’d be dealing with a very, very subjective side of people’s consciousness, treading on some very hallowed ground. To interpret Christ any way different from the way the Bible depicts him, you’re asking for a lot of trouble.

HACKETT: What is it you have in mind for your “grand period piece in the religious genre”?

STALLONE: Well, I deal with the spirituality of life in the everyday meaning—man looking to the god-force within himself, which is his soul. That’s the temple.

HACKETT: I’ve heard that your brother Frank is a Scientologist and—

STALLONE: Well, I don’t know. He was reading the books about it, but I don’t know if he actually joined yet. He may have, but…

HACKETT: And I remember a few years ago seeing a picture of a man and a woman in the National Enquirer, and they reminded me a little of the couple in the Honeymoon Killers… You know who I mean?

STALLONE: Ohhhh yeah.

HACKETT: And it said they were your spiritual advisors? That you’d contributed to them or something?

STALLONE: Financially? No. what it was, was they belong to the Church of New World Unity. And she was real interesting. I talked to her about six, seven times, and she would do spiritual readings. I got something out of it. It was part of my education. I haven’t been there for years.

HACKETT: I know your wife did astrology, but am I wrong in remembering that your mother did, too?

STALLONE: Still does. Palmistry, numerology…

HACKETT: And you’re still interested in that stuff, too?

STALLONE: Oh, very much. There’s too much in it to be coincidental.

HACKETT: How did you decide to do First Blood? Were you advised to take the role?

STALLONE: It was supposed to be a very dark, brooding film, and my stars weren’t so good, but the characters’ were, and the film’s aspects were excellent. That’s what counts. Sometimes mine look good and the film’s stink.

HACKETT: Are you ever going to return to the theater?

STALLONE: That’s a very good question, because I think in a few months I’m going to cross over that line. Theater is like boxing—having the audience ringside. It’s instant gratification. [laughs] Or horrification.

[Everyone breaks for lunch, and Stallone goes off to meet with the New York art dealer who advises him on his collection. When he comes back, he steps into the makeup trailer and sits down with a book called Nineteenth Century European Painting in his lap]

HACKETT: What kind of art are you buying now?

STALLONE: Oh, let’s see. I buy many young artists like Mentor, Schuyff, Hambleton, Cheverny, Kunc, Roloff, Drake.

HACKETT: What styles are they?

STALLONE: Mostly neo-surreal. Putting reality into a blender and coming up with a whole different set of rules.

HACKETT: Do you rely exclusively on people to show you things you might be interested in, or do you get out yourself to the galleries to look at stuff?

STALLONE: Absolutely. In fact, I’m thinking of starting a gallery. I’d live in a museum if I could. I used to spend hours and hours in the Museum of Modern Art.

HACKETT: Do you think that if you’d spent hours and hours in the Metropolitan you’d be buying different art now?

STALLONE: Oh, but I do collect traditional art, too. I’m very hung up on the late 19th-century artists. Mostly Romantic. I think that the great artists—the majority of them—are dead. We don’t have many today who have the draughtsmanship. Most of my bronzes are Baryes, I have Menes, I have Rodins. I bought a Bourdelle sculpture of Heracles as The Archer—a beautiful piece—and I just bought a Delvaux. But again, I also love established artists like Botero, and Robert Graham.

HACKETT: The guy who did the male and female torsos for the Olympics?

STALLONE: Right.

HACKETT: What does the concept of “art” mean to you?

STALLONE: Art is the ability to communicate through an intermediary and to convey one’s feelings through an isolated object. It’s inspiration and incubation. Putting my subjective feelings into an objective form and then on to you for a subjective interpretation.

HACKETT: Can a movie ever be art?

STALLONE: Flashes. Moments. To be really artful, though, you have to be subjective and so singular. Movies are a collective art. Art by proxy.

HACKETT: Besides Poe, who are some of your favorite authors? What do you read?

STALLONE: Right now I’m reading Gödel, Escher, Bach. [laughs] You ever read that one?

HACKETT: No. tell me about it.

STALLONE: It’s about the correlation between Bach’s music, Gödel’s mathematics, and Escher’s drawings. It’s in a sense a real mind-bender. You read about 20 minutes and then your brain is fried. You have to go out and get some air. And then I’ll read Anatole France, Revolt of the Angels, things like that. And then I read a great many of the periodicals looking for material, finding out what’s going on. Now and then you’ll find an interesting piece, real detailed, a treatment in itself.

HACKETT: What TV shows do you watch?

STALLONE: I watch a lot of news, and I watch musical shows because I think the music of the young people is really their news reports. They let you know how their country is going through their eyes, and about their experiences in the everyday shock of growing up. So that’s very interesting to me.

HACKETT: You sang the theme song of Paradise Alley, and then there was “Devil With the Blue Dress On,” in Rhinestone. Are you ever going to sing again?

STALLONE: Uhhh… [laughs] You know, the truth is that it was an experiment. I was trying to do more of a farcical-type singing. The original concept was that Dolly [Parton] would try to take a blitzed-out, heavy-metal, Black Sabbath-type of punk singer who comes out wearing a cape made of razor blades—really hardcore—that she would try to take him down to, you know, Elephant Hollow, Tennessee. That was what was going to be funny.

HACKETT: you seem like a guy who enjoys a good splash of cologne. What about it?

STALLONE: I do. I use Armani, I use Cardin, Grey Flannel, I use Boss, I use Lagerfeld.

HACKETT: Just whatever you grab, or when you feel a mood?

STALLONE: You name it, I use it.

HACKETT: And your clothes. Nobody else dresses like you. You’ve always kept the same look, the same kind of cut, and you wear a lot of white… Do you have them made? Who’s your idea of a great dresser?

STALLONE: It’s more like an era. There were so many excellent dressers in the ’30s and ’40s. Like George Raft. You know, really superior dressers who spent a lot of time on their “look.” And I like that a great deal. There’s just three colors that I work with—grey, black, and white. And between those three, you’ve just about got it. Brown to me is a sleepy color. It’s nice, but it’s sleepy and peaceful. But the black means business, the white is more sublime, and the grey is your go-between, an arbitrary position. I have my clothes made because it’s hard to find them already done like that. But I do buy certain designer clothes, too. And most of my shoes I usually have made for me because I have bad feet from jumping and boxing so much.

HACKETT: Are you still involved with polo? Do you still have horses and play?

STALLONE: I was, but…

HACKETT: You still ride, though, don’t you?

STALLONE: I guess the best thing I do of all is ride. Horsemanship, I have a natural flair for it.

HACKETT: You do dressage and all that?

STALLONE: I do it all. Polo ponies, five-gaited, three-gaited. I’m not a very good jumper, because I’ve never really liked jumping. But the warlike movements that you get in polo I like, I feel very good about. Polo is like tennis—you literally have to live it [stepping out of the makeup trailer Stallone gestures around the MGM lot] and give up all this.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE SEPTEMBER 1985 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs on Wednesdays. For more, click here.