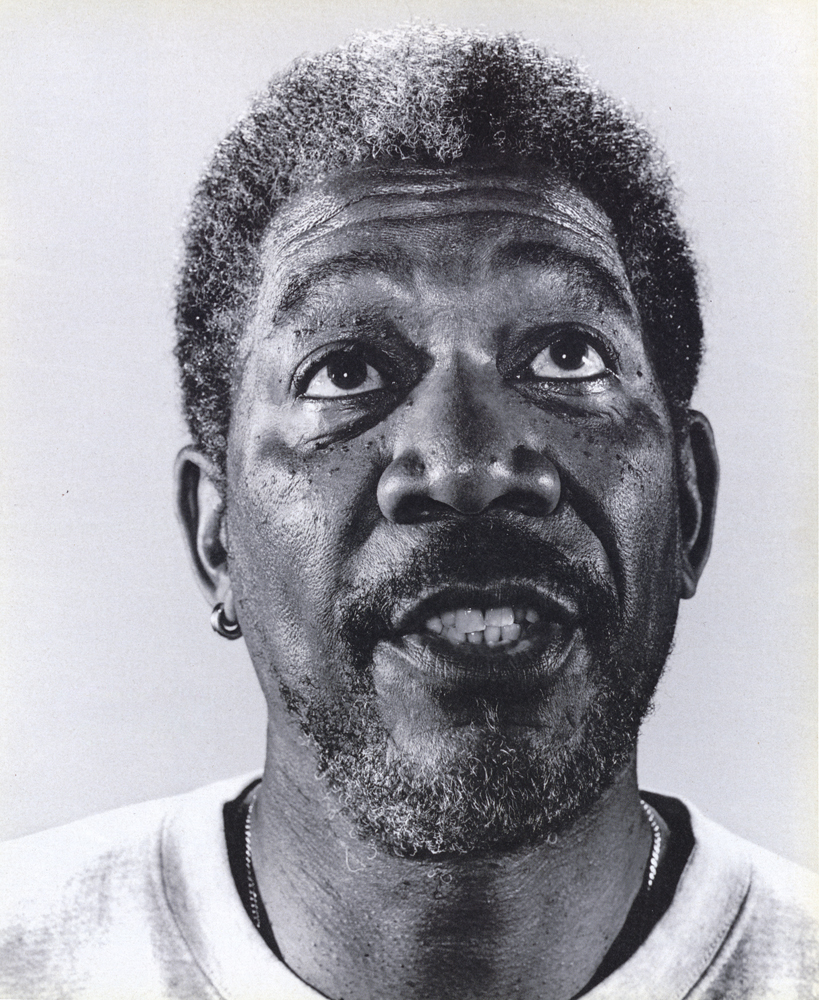

New Again: Morgan Freeman

Morgan Freeman has always been a formidable force in cinema—and not just because he’s played God in two of his movies. Freeman has written himself into Hollywood history with an acting career that spans the course of almost 30 years and includes 45 films, one Oscar win, and four nominations. It should come as no surprise then, that last week, The Film Society of Lincoln Center named him the recipient of the 43rd Annual Charlie Chaplin Award.

To honor this achievement, we look back to an interview with the actor from June 1996 (when Freeman was doing press for Moll Flanders), in which he discusses topics ranging from Mississippi and Memphis to Blaxploitation films and black representation in Hollywood. Today, as controversy surrounds the 88th Academy Awards, with #OscarsSoWhite stirring the debate amongst stars and viewers alike, it seems that Freeman’s past words could not have come at a better time. —Sidney Butler

Free Man: Is Morgan Freeman the noblest actor of them all?

By Graham Fuller

We live in an era of vigorous black stars—Denzel Washington, Wesley Snipes, Danny Glover, Samuel L. Jackson, Laurence Fishbourne—who make their white equivalents tepid in comparison. Sixty next year, and therefore an elder statesman amongst that group, Morgan Freeman has tended toward character parts since his Oscar-nominated performance (the first of three) in Street Smart (1987) put him on the map. Yet how can we think of him as a supporting player? What would Clean and Sober (1988), Glory (1989), Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), Seven (1995), or even Clint Eastwood’s masterpiece Unforgiven (1992) be without him? Shrewd, grave, and authoritative, Freeman is one of the most reliable presences in American cinema, an actor who ennobles every film he’s in. More than that, he has dignified the black experience in his movie by not advertising it. He habitually makes notions like Uncle Tom-ism and political correctness shrivel at his feet, even in a film as self-consciously liberal as Driving Miss Daisy (1989).

Freeman appears as the longhaired, long-suffering factotum entrusted with Moll’s pesky daughter in this month’s Moll Flanders (which has little to do with Daniel Defoe’s novel) and plays what he describes as “a shadowy character” in the action thriller Chain Reaction later this summer. He had just arrived in North Carolina to begin filming another thriller, Kiss the Girls, when he talked to me—in familiar, gentleman tones—on the phone.

GRAHAM FULLER: I know you were born in Memphis toward the end of the Depression. What comes to mind?

MORGAN FREEMAN: Nothing. [laughs] My parents were working in a hospital in Memphis. But I didn’t live there for any length of time that I remember. The first thing I remember is the town in Mississippi that I live in now, Charleston.

FULLER: What memories do you have?

FREEMAN: Oh, gee…Hot summer days, mostly. Running. Dust. Sweat. A few names. One of my uncles had either a Ford or a Chevrolet. The war started in ’41, and two of my uncles were called away.

FULLER: What about your father?

FREEMAN: He enlisted, but he didn’t last. [laughs] He was not war material.

FULLER: What kind of kid were you?

FREEMAN: I played a lot. When I was a teenager, I began to settle into school because I’d discovered extracurricular activities that interested me: music and theater. I became what I supposed you would call a rather serious student. I functioned on attention, I think, and I was getting a lot of attention at school.

FULLER: Do you have brothers or sisters?

FREEMAN: One sister and three brothers. Another brother shuffled off his mortal coil at an early age. He was a teenager in the Marine Corps.

FULLER: Did he die in Korea?

FREEMAN: No. He died at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Drowned. Very ignominious. All of us, except my youngest brother, were in the military. I joined the Air Force. I took to it immediately when I arrived there. I did three years, eight months, and ten days in all, but it took me a year and a half to get disabused of my romantic notions about it. When I was getting close to being accepted for pilot training, I was allowed to get in a jet airplane. I sat there looking at all those switches and dials and I got the distinct feeling that I was sitting in the nose of bomb. I realized my fantasies of flying and fighting were just that—fantasies. They had nothing to do with the reality of killing people. What I wanted was the movie version. So that was the end of the whole idea of doing anything other than acting for me. I’ve never had any other vocation.

FULLER: Did you then decide you were going to be a movie actor or a stage actor?

FREEMAN: Movie actor. I went to [Los Angeles] City College and took acting classes. [laughs] But I almost flunked.

FULLER: Did you feel defeated?

FREEMAN: No. I was told that I was good in my dance movement classes and that I should concentrate on dance because it would enhance my ability to get acting work. But I was 22 before I took my first dance class. I had never been athletic, so I was very stiff; I still am. I think what I got mostly from dance was carriage.

FULLER: What was your next move?

FREEMAN: It was to try to get acting parts rather than dance work. I got a job as a member of the Inca chorus on a bus and truck tour of The Royal Hunt of the Sun in 1966. I had also had an understudy part, and one night we were in Des Moines, and I got to go on. The feeling of rightness and power that washed over me on the stage that night came as a revelation to me. I said to myself, “This is what you do, this is where you really shine.” The following year, I got my first job Off-Broadway in a play called Niggerlovers.

FULLER: Immediately after that you were in an all-black version of Hello, Dolly! with Pearl Bailey on Broadway. Was that a big step for you?

FREEMAN: It was work. Every job was a big step. My career had gotten kicked into gear around that time, and I was moving from job to job. I worked Off-Broadway, in regional theater, doing original plays, old plays, Brecht, a lot of interesting stuff. I did little bits and pieces of television, soap operas, walk-ons in movies—I did my first extra job in The Pawnbroker in New York in 1963—then I did Electric Company [a PBS reading program for children] on television from ’71 till ’76.

FULLER: You missed that whole period of Blaxploitation movies.

FREEMAN: I knew a lot of people who were working in those films, and I remember saying to my agent, “Listen, everybody’s going out to Hollywood and making movies. I think I ought to go out there.” And his advice to me was, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. If they want you in Hollywood, they’ll send you.” And sure enough, they did. I did some television movies around ’78 and ’79 and then in 1980 I was in Brubaker.

FULLER: But it wasn’t really until you played the pimp in Street Smart that—

FREEMAN: —that I got another kick in the pants.

FULLER: Well, we got one, too. That was the film that—

FREEMAN: —sprung me loose. It let me go.

FULLER: Had you been working on developing technique during all this time?

FREEMAN: Just working. I had gone to school to work on technique and found it wasn’t something that was really worthwhile to me, although it probably was. It seems to me that I never grow unless I’m actually working with other actors who have shed whatever shell it is that keeps them insulated from each other.

FULLER: In the late ’80’s, black filmmakers and actors—including Spike Lee, Denzel Washington, and yourself—suddenly seemed to get their chance. Do you think there was a change in consciousness?

FREEMAN: Yeah I do. I think there was a change of consciousness in the country as a whole around that period, for a number of reasons. It goes back, I think, to the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the advent of the Carter era, which had a softening effect on the country. By 1984, when Jesse Jackson made a credible run for the presidency the black exploitation period in the movies had come and gone, and then there was a resurgence of different kinds of stories involving black people. At the same time, the actors’ unions were making a push toward open casting. It all reached its zenith with the success of The Cosby Show. So a wave began to happen, and we were all lifted with that wave.

FULLER: In the past year or two however, there seems to have been a slight abatement in the number of films directed by blacks compared with four or five years ago.

FREEMAN: What’s important is that directors like Spike Lee, John Singleton, and Bill Duke are all still working.

FULLER: What did you think of Jesse Jackson protesting the lack of jobs for minorities in the entertainment industry on Oscar night? Certainly no blacks were nominated for acting Oscars this year.

FREEMAN: I don’t think you’re going to get nominated every time you jump out of the box. See, Jesse and I have different agendas. Jesse is a noisemaker. He’ll create whatever noise he needs to create to effect the kinds of changes he wants to effect. Jesse and I want to effect the same kinds of changes, but I like to do it with a different kind of noise. I would never complain that Hollywood is racist when I’m one of the people touted as a welcome entity there. If we were to complain, we’d have to say, “We can’t get work because ‘they’ won’t let us.” But then you’re just empowering the “they.” You don’t want to do that because there’s already this thing in this country, which, legitimately, because of our history, has given blacks an underdog mentality.

FULLER: Do you think there’s any way to change that?

FREEMAN: We better change it. As long as you feel like a victim, you are one. There was a scene near the end of Roots [The Next Generations, 1979], in which Alex Haley interviewed George Lincoln Rockwell [the leader of the Nazi Party] for Playboy magazine—it was [like] James Earl Jones and Marlon Brando. [laughs] Haley asked Rockwell why he hated blacks, and he said, “Because you never did anything. You’re always whining and moaning, but you never made a contribution.” And we can all sit here and listen to that and think, Gee, I don’t know of any contribution we made, other than picking cotton and moaning. But that’s not true at all. We have glorious history here. We fought every war. We’ve done everything there is to guarantee our right to whatever rights there are to be had by an American. So, O.K., if you have the right to rights then take them. I don’t feel like I’ve got to ask for anything.

FULLER: Let’s talk a little bit about Bopha!, the movie you directed in 1993. It’s the one of the most effective films about apartheid in the way it shows this black South African family—the father [Danny Glover] a cop, the son [Maynard Eziashi] an anti-apartheid activist torn apart by their different beliefs. It reminded me of how brothers fought brothers in the American Civil War. How did Bopha! come up?

FREEMAN: I was approached to play the lead role and was offered the directorial-ship as a sop. I didn’t want the lead role, but I thought it’d be a good opportunity for me to try directing. I’d be out of the country filming in Zimbabwe, and it seemed like a small film, although it didn’t turn out to be that small. It was a wonderful experience on almost all fronts. The one thing that wasn’t quite so wonderful was having to deal with the studio heads sitting making decisions thousands of miles away.

FULLER: Did they give you a certain amount of freedom though?

FREEMAN: Give me a certain amount of freedom? I took a certain amount of freedom. [laughs]

FULLER: Were you happy in the end of what you did as a director?

FREEMAN: I found I had a feel for the fieldwork of directing. I’d just come from Unforgiven, where I’d had my best lesson in directing from Clint Eastwood.

FULLER: Unforgiven doesn’t always draw attention to the fact that your character is a black man, which is unusual for a western.

FREEMAN: That would have been apologetic, so I’m grateful for that. But then again the character wasn’t written black either.

FULLER: You brought great dignity to the role, as you often do. Is that dignity—

FREEMAN: It has nothing to do with me. I don’t know anything about that. It’s not like I wake up in the morning and say, “I got to be dignified today.” If the characters seem dignified, it’s because they were written that way. I don’t want to go around talking about how I feel about honesty and all that stuff, but if you can find where the kernel of a character’s soul is, if you can somehow plumb that, then it’s easy to play. I think that sense of dignity has to do with the fact that there’s an inner life that’s readable more than anything else.

FULLER: In Seven your character was dignified but also troubled. Given the dark mood of that film was it a hard one to do?

FREEMAN: Not at all. I seldom get into the mood of the story. It’s acting. I go in, I act, I quit. [laughs] I don’t take anything away from it.

FULLER: What attracted you to Moll Flanders?

FREEMAN: Well let’s go back to Robin Hood. Pen Densham [co-writer of Robin Hood: Prince of Theives and writer/director of Moll Flanders] had the inspiration to create my character in both of these movies—and they are historically correct. One criticsaid of Robin Hood, “Well, I don’t know if you would have seen a black man in England in the 12h century.” That sort of sums it up: “I don’t know,” he said. Right. He didn’t know. There’s a lesson to him. The same with Moll Flanders.

FULLER: Do films like Robin Hood and Moll Flanders challenge you?

FREEMAN: Every job’s a challenge. The challenge is to do it and make it look right, like you belong there—wherever that is.

FULLER: It seems to me that you’re not too reflective about your career and that you don’t spend an awful a lot of time weighing what could have been and what might be. Is that a philosophy for you?

FREEMAN: “Should, woulda, coulda—it’s all the twilight zone of the subjunctive mood.” I read that somewhere. That sums it up very well for me.

FULLER: So you like to do in other words?

FREEMAN: Right.

FULLER: And if I can ask you to be a bit reflective, are you happy with the way things have gone?

FREEMAN: Ecstatic. It couldn’t be better.

FULLER: After all these years you’ve decided to make your home in Mississippi. You haven’t strayed too far from your roots.

FREEMAN: I have on a level. In other words, my roots were pretty far removed from high income. It’s interesting to be back there at the level of income I have now, at this stage in my life. Growing up in Mississippi, I realized that it was separate and unequal and all that, but it was still a safe place.

FULLER: Do you have family?

FREEMAN: I have four children and nine grandchildren. I’m presently wearing out my second wife.

FULLER: What’s her name?

FREEMAN: Her name is Myrna Colley-Lee. She’s a costume designer, currently working at the Crossroads Theater in New

Jersey.

FULLER: It sounds like things are going well for you. I hope we see a lot more of you.

FREEMAN: Thank you. So do I.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JUNE 1996 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.