New Again: Kathryn Bigelow

Less than a decade ago, Kathryn Bigelow became the first female director to receive the Academy Award for Best Picture, for her 2008 drama The Hurt Locker. Bigelow’s career, however, extends far beyond that achievement. A former painter, Bigelow’s first feature as a writer and director, The Loveless, starring Willem Dafoe, came out in 1981. Today she is known for the cinematic tone of her films, which feature precise composition and a dark ambiance, and are always imbued with social and political criticism. Since The Hurt Locker, Bigelow has made another monumental film, Zero Dark Thirty, about the manhunt for Osama bin Laden, and has tested her strengths in animation and VR to create two documentary shorts about ivory poachers in Africa, Last Days and The Protectors, respectively.

Out next month, Bigelow’s newest film, Detroit, investigates the aftermath of the 1967 12th Street Riot—one of the most lethal, racially charged riots in American history—and the Algiers Motel Incident that resulted in the deaths of three black men at the hands of white police officers, later tried and acquitted. Topical and scrutinizing, Detroit is bound to stir up conversation.

In anticipation of its release, we take a look back into Bigelow’s own history with an interview from our September 1989 issue, where she discusses the difficulties and joys of making her first films. Twenty-eight years later and seven features later, Bigelow continues to challenge and excite her audiences. —Zuzanna Czemier

Dark by Design

By Victoria Hamburg

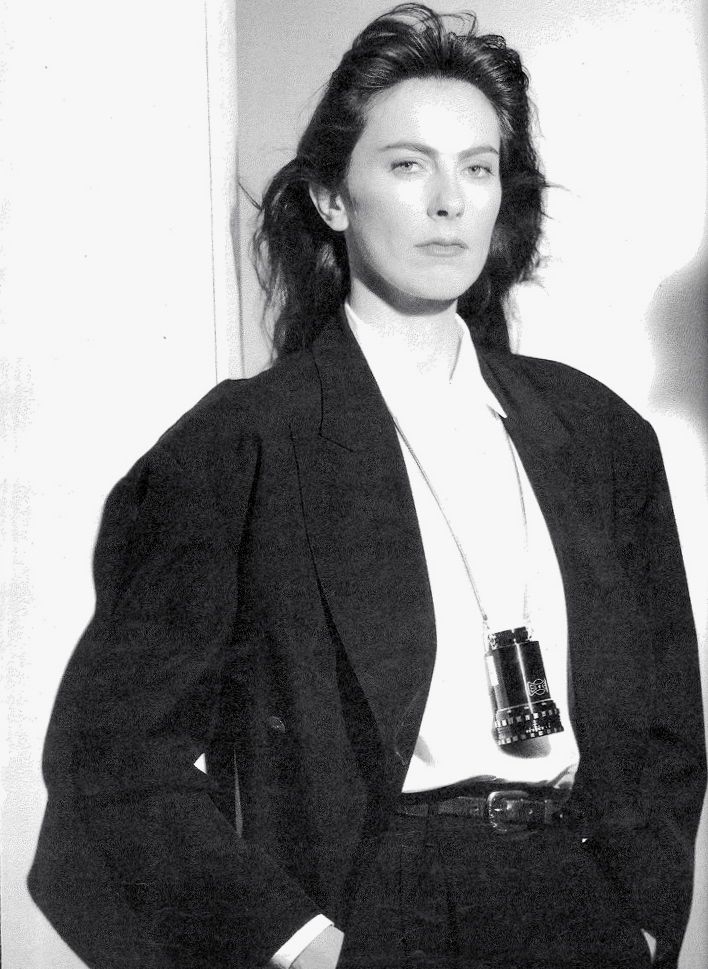

Kathryn Bigelow’s film works—The Loveless, Near Dark, and the new Blue Steel—are cinematic walks on the wild side. Fellow filmmaker Victoria Hamburg met with the director in New York during an editing session of Blue Steel.

Writer-director Kathryn Bigelow makes tough, violent movies. Her first feature, The Loveless, in which a motorcycle gang faces off against small-town rednecks, starred Willem Dafoe and rockabilly star Robert Gordon. Four years later she gained a small cult following with her second feature film, Near Dark, a mixed-genre tale about a young man who falls in love with a beautiful teenage vampire and joins her blood-sucking family on a gory rampage through the wild Rest. Bigelow’s new picture, Blue Steel, co-produced by Oliver Stone, is an action thriller about a rookie cop, played by Jamie Lee Curtis, and a psychotic killer (Ron Silver) who become obsessed with each other.

The child of a paint factory manager and his wife, a librarian, Bigelow grew up in northern California and studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute. She entered the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program in New York in 1972 and began experimenting with film while working as an assistant to Vito Acconci. Her first short, Set-Up, made at Columbia’s graduate film school, is now part of the Museum of Modern Art’s film collection. Tall, willowy, and in her mid-thirties, Bigelow speaks in a surprisingly soft, girlish voice. We met in an empty production office in Manhattan while she was completing the final cut of Blue Steel. She was eager to return home to Los Angeles and be reunited with her fiancé, James Cameron, the director of Aliens and The Abyss.

VICTORIA HAMBURG: It seems to me that you’re exploring genre films in an interesting way. I’m wondering, are you defining ultimate archetypes?

KATHRYN BIGELOW: What interests me is treading on familiar territory. With the motorcycles and vampires, it makes the audience comfortable to know that there’s something familiar; i.e., there’s the genre thread through it. Then I try to turn the genre on its head or make an about-face, and just when I make the audience a bit uncomfortable, I go back and reaffirm—”Yes, it’s all right.” But it isn’t necessarily conscious. I am keeping within the sense of something familiar, then trying to expand it, push its limitations. Maybe in the case of Near Dark, which is more like a vampire Western, there’s a bit of hybridization of genre. I also think in Blue Steel there is a mutation that maybe implies a different genre.

HAMBURG: But instead of avoiding the issue, you embrace clichés. I think there’s always some truth in clichés.

BIGELOW: Oh, absolutely. But again, the use of cliché is not a conscious approach. It’s just a matter of working within a construct that is familiar and then subverting it in order to reexamine it.

HAMBURG: Do you think that by doing so you create a climate of safety that allows you to take the audience somewhere they might not ordinarily want to go?

BIGELOW: Possibly. Otherwise, I don’t know if they’ll take a ride with you. They want to; they’re not going to balk at something new if you approach it a certain way. Just when they think they know exactly what’s going on in the story, something happens, and they say, “Wait a minute. I thought this was a horror movie.” Suddenly, they’re seeing a showdown, and it should be high noon, but it’s midnight.

HAMBURG: I also think there’s an amazing sense of space, a painter’s composition, in your films—long horizon lines. When I read the script for Blue Steel, I wondered how you would approach shooting in Manhattan.

BIGELOW: It’s not a spacious landscape. In a way, the film’s landscape is internal and psychological. It’s a film of people—faces and eyes and behavior. Near Dark was a film about light and the absence of light—which implies great space and atmosphere. Blue Steel is really within the context of the mind, so it’s telescoped, which doesn’t immediately imply as visual a canvas. But it looks exquisite. It’s a clutter, an extraordinary sort of tribute to capitalism.

HAMBURG: It’s also schizophrenic and psychotic—which is what New York is partially about.

BIGELOW: Yeah, it’s an urban nightmare. There’s this compression and a clutter of people and buildings. Whereas Near Dark takes place in the West, and there’s an incredible expanse.

HAMBURG: Just from a nuts-and-bolts production standpoint, was Blue Steel harder for you?

BIGELOW: It was definitely physically and logistically tougher. So many productions take place in New York. New Yorkers know that there’s nothing novel about a film shoot—there’s nothing educational or fun. They don’t want their routine interrupted, because it’s happened so many times. Whereas you go to a place like where we shot Near Dark—a town called Coolidge, Arizona, near Phoenix—and the entire town will bring box lunches and picnic trays and come watch the shoot for fun. There’s a sense of camaraderie. Here, you work in spite of the city, but on the other hand, you have a sense of authenticity. This entire picture was shot on location—no studio sets at all, which can be very difficult. The city is an incredible pool of talent, and as a city it tries to make things work for you. For instance, we had a couple of shots down on Wall Street at rush hour. There were probably two million people walking within a single shot. There are logistic problems that you would never face in any other situation.

HAMBURG: I wondered about that. There’s that whole shoot-out scene right down on Wall Street.

BIGELOW: We made a lot of people very unhappy.

HAMBURG: How long did it take you to do that?

BIGELOW: About a week. We really did disrupt their world. Also, we actually shot in the commodities exchange during business hours, in the gold pit. The character Ron Silver plays is a trader. There we were—gold was being traded, we had an actor in the pit while people were trading, and I was thinking to myself, am I affecting world commerce? Regardless of whether I am or not, I’ve got to get this shot.

HAMBURG: So when the gold market crashes, they’re going to blame you.

BIGELOW: A couple of people didn’t realize Ron was an actor at all, because he was so effective. He’d done his homework. They would start trading with him, and then I’d say “Cut.” One of the guys who actually tried to buy from him said, “Cut? What do you mean ‘cut’?”

HAMBURG: What did you do?

BIGELOW: We . . . sorted it out. The president of the exchange was also in the shot. He was very helpful and explained everything to the trader—this guy had come in late, after everybody else had been alerted.

HAMBURG: Do you think the audience has reached a point where they’re jaded by violence? It seems there’s got to be a certain amount of violence in a cop movie or a psychological thriller before the audience will take it seriously. Otherwise, they’ll say it’s too arty.

BIGELOW: Yeah, I think you always tread that line. You also have to be careful not to make an exploitation film. You want to try to give it an edge, a kind of adrenaline, without compromising. You try to do it within a context that has integrity. So it’s a fine line. You don’t want to pander. On the other hand, if the audience is expecting something consistent with the genre that is defined, their expectations are going to be in contradiction to what you’re delivering. I think if you can do it intelligently or give them the framework in which their expectations are being met, the violence may not be as gratuitous as it could be. Then I think that you’re doing something.

HAMBURG: When you’re doing scenes like the shoot-out on Wall Street, do you rehearse the actors a lot beforehand? Do you have much time on the set to work with them when there’s so much going on logistically?

BIGELOW: It’s difficult to rehearse something like that. In a way, that kind of thing is pure cinema. It’s all constructed in the editing room. It’s a series of shots. You’re not actually letting the actors work to the best of their ability, the way you can in a dramatic scene, when they work with nuance. Character can evolve within the context of a scene with dialogue, but when you’re in a situation where the person is simply surviving, it’s very cinematic. I like to rehearse ahead of schedule—just go through the script and read it through. Not necessarily for performance, but for clarity and understanding, character, background. My fear-it’s interesting, because this is a real departure from theater—is that all of it might become mechanical. It’s always a fine line.

HAMBURG: I was wondering if you have any mentors, people who have protected you.

BIGELOW: Protected . . . I don’t know.

HAMBURG: Or encouraged you.

BIGELOW: Yes. I mean, there are people whose work I truly admire and learn from. And, for instance, Oliver Stone helped Blue Steel get made. Without his involvement, it would never have been made.

HAMBURG: How did that happen?

BIGELOW: It’s a long story. In 1983, Walter Hill had seen The Loveless and cast Willem Dafoe in Streets of Fire. He was also setting up a producing deal at Universal and asked me what I was interested in doing. I pitched him a story about gangs in East Harlem, Spanish Harlem. I was interested in writing and directing, and he was to be the producer. Universal developed it, but various studio head changes followed, and the project ended up gathering dust somewhere, I think at Columbia. Oliver Stone read the script, and he was interested in doing a project on South Los Angeles gangs. He asked me if I wanted to write it with him. We did some research down in South Los Angeles, where there are like three hundred homicides a year. Extraordinary. Twenty minutes from downtown Los Angeles, you have this place where you think the National Guard should be brought in. Anyway, just when we were about to begin that project, Salvador got under way, and then Oliver did Platoon. Meanwhile, I made Near Dark. He saw it and called me up and said, “I’m interested in whatever you want to do next. If it helps, I’ll produce your next picture.” I sent him Blue Steel, and he loved it. He shepherded it to Ed Pressman, who was able to get it financed. I guess having someone like Oliver behind it gives it a kind of credibility. To be out there solo can be difficult. It’s a very tough piece, with a woman at the center of it who goes through hell. It’s not a comedy. This is a tough sell.

HAMBURG: How do you feel about those projects that got shelved? It must be hard to be out there pushing one and then suddenly find it’s on hold.

BIGELOW: The first few times it happens, you are emotionally devastated. Then you realize it’s all a big waiting game. It’s an inevitable process, and you just try to stay alive and not to let it beat you. You have to triumph over it. It’s simply the law of averages. You keep writing. It’s a crapshoot, and one script will ultimately make it.

HAMBURG: I always wonder how aggressive you have to be out there.

BIGELOW: It’s like a feedback loop. There’s a certain kind of aggression that’s necessary. You’re out there making a picture and trying to follow your schedule; you’ve got X number of shots to do. There’s a certain kind of mindset that you have to get into or you’re not going to make it. You see this kind of transformation, a metamorphosis, happening, but it’s a necessary evil.

HAMBURG: Do you come from a big family?

BIGELOW: I’m the only child. What’s interesting is that your parents become your peers, as opposed to sort of the “other.” I’m obviously talking from only one perspective.

HAMBURG: When did you decide to be a filmmaker?

BIGELOW: Not until the mid-’70s. Up until then I was painting and always thought I would make art of some kind. My understanding of film was cursory. I went to films as anybody does, purely for entertainment. After I moved to New York and started making art seriously, I began focusing on European films rather than American cinema. With art everything had a big historical context, and I looked at film in the context of art. My knowledge of film was so limited that everything was exciting. I was just out there with a small crew. I didn’t even know that what I was doing was called directing. I had the equipment, I had a camera, I had the lights. I kind of knew what I wanted to do, and was making these small films.

HAMBURG: Were you taking film courses?

BIGELOW: No, I did that after I started shooting. I really came into film as a naïf. And in a way I want to preserve that, because I was making art.

I came to New York when I was nineteen, and someone told me that the Whitney Museum had a great independent-study program. My teachers were Susan Sontag, Richard Serra, Robert Rauschenberg. Fantastic people would come down and give lectures. I took it so seriously, it was almost paralyzing. Then I got involved in conceptual art, so the hand, the colors, and all of that were dissipated. I had a series of odd jobs. One was working for Vito Acconci, putting together films which would run as loops for one of his shows at Sonnabend. He used to have these sayings on the walls. As I was filming them for him a light bulb came on.

Somehow I commandeered a camera, got a crew of friends together, and shot something. I was very interested in the idea of violence being seductive. Again, it was all from an analytical standpoint. I ran out of money and got a scholarship for graduate school at Columbia. Milos Forman was the co-chairman of the film division, and we had a lot of access. Peter Wollen was one of the teachers. He was great. He’s illuminating. Until I met him I was just looking at light reflected on a screen. After that it was more like a window. I graduated and wrote The Loveless.

HAMBURG: In The Loveless,after the young girl shoots her father, she comes out of the cocktail lounge and gets into his car. Then she puts the gun in her mouth and shoots herself. Willem Dafoe’s character just stands there and does nothing. He’s just been to bed with her, but he does nothing, while she kills herself. What was that supposed to mean?

BIGELOW: Probably only in retrospect, when you’re asked questions like that, do you try to put references together. When you’re writing, things are very abstract. There isn’t the sense of a message per se. That character’s story has more to do with the fact that she had triumphed over her father; suicide was for her a form of triumph. She did not want to be saved. Willem Dafoe’s character respected her decision, even though it could be argued that she was too young to make a decision like that and desperately needed help.

HAMBURG: But how could another human being watch and let her do that?

BIGELOW: It’s very nihilistic—a certain kind of anger. But I really argued that her suicide was an act of triumph, even though in retrospect it seems very shocking. At the same time, given the context and given the future that she would probably face, maybe it was the strongest choice she could make. On the other hand, given that it was the 1950s, the nightmare she was in probably couldn’t have been resolved any other way. So I don’t know. It’s just one of those things where you’re writing and it’s very intuitive, sort of abstract.

HAMBURG: When I read Blue Steel it also struck me that you’re really hard on men. There’s a sense of anger in both of those films. In Blue Steel, the woman cop’s relationship with her father is bad—her father’s very violent and beats her mother. She finally falls in love with a man who is a psychotic, who kills her best friend.

BIGELOW: [laughs] You think there’s something the matter with that?

HAMBURG: It does seem a little angry.

BIGELOW: There’s anger there, but I don’t think of it that way. It’s not like I’m channeling anger that should otherwise be focused on an individual. Not at all. It seems to be what is necessary for that character in Blue Steel, for the evolution of that story. In other words, her back story had to be very difficult. Becoming a cop probably gave her the strength, for the first time in her life, to stand up to somebody that she had wanted for twenty-five years to stand up to. But now something has changed internally. The character in Blue Steel is interesting to me because she’s very human. She’s flawed; she makes mistakes… I think that’s universal.

HAMBURG: Also, when she makes mistakes, it’s treated very harshly. She doesn’t get away with it.

BIGELOW: No. [laughsHAMBURG: She gets suspended. Her best friend gets killed. Life goes really bad when she makes a mistake.

BIGELOW: [laughs] It’s not a good day. Dark, dangerous situations. I try to ask myself why I’m drawn to that kind of material. It has an energy; it’s very provocative. I think it’s important to challenge.

HAMBURG: Her suicide made me wonder what kind of world you think we live in. It seemed hopeless.

BIGELOW: Ultimately, her decision over her life is her own responsibility. In other words, relinquishing that to somebody else would have weakened her.

HAMBURG: Would you make it differently if you were doing it today?

BIGELOW: I don’t know if I would. You know, with the flashback of her laughing, one can be left with an image of what is, in the context of the film, her happiest moment. I’ve never tried to argue the notion of triumph. In a way, Blue Steel has a little in common with The Loveless. It’s about someone finally coming to terms with something that she has found impossible to come to terms with before. The circumstances she falls prey to give her a chance to act.

HAMBURG: Filmmakers who aren’t just hired guns, who are doing movies that somehow relate to a personal view of the world, may, in a sense, find themselves making the same movie over and over again.

BIGELOW: I think even if you are a hired gun there’s an obligation to personalize. On the other hand, it’s the old paradox. If you’re making art, you are truly investing time and energy in a very personal creative desire. You can be very pure. On the other hand, there’s art coupled with commerce. There’s a point where your personal desires have got to work with respect to the economics.

HAMBURG: With Blue Steel, the stakes are higher than with your other two films. The people involved in it are on a much higher level. Did you have a sense of interference or strong guidance?

BIGELOW: Guidance, yes.

HAMBURG: So you didn’t feel you had compromise?

BIGELOW: No. I think if you get to a point where you feel you are compromising, then you risk losing the thread of integrity that the reason you wanted to make the film in the first place. If you’re trying to satisfy many different people’s expectations, poses a real risk to the material.

HAMBURG: Is there great pressure in Hollywood to compromise?

BIGELOW: Well, pictures have a tendency ultimately to be made by a committee. You’re trying to satisfy an audience that is perhaps a kind of animal that nobody can predict. It’s really a judgment call. All you can do is hope and rely on the support of the people who hire you. If you’ve created the project and then taken it through realization, that gives you an important kind of leverage. Someone like Ed Pressman has a history of making films with people who have carried the project inception to realization. He’s been outspoken about trying to protect that concept. But it’s always tenuous, because are at the service of an audience, which is fickle, and you’re also in an industry very competitive.

HAMBURG: What are you doing next?

BIGELOW: New Rose Hotel, I hope, by William Gibson.

HAMBURG: What attracted you to that story?

BIGELOW: Probably its noir aspects. All of Gibson’s material has incredible landscapes. To be honest, it was very hard to choose a story to do. He was particularly fond of the piece, so that also affected my judgement It’s about a character who is on a spiral from which he can’t retrieve no matter what he does. The more tries to relieve himself, the more stuck he is. It’s a wonderful ride.

HAMBURG: There’s also an interesting relationship between a man and a woman in that story.

BIGELOW: Wonderful. In the short story, she’s classic femme fatale, but as she is the script, she has incredible strength. And he benefits from that. So even though ultimately it’s not a wise move when throws his lot in with her for emotional reasons, it’s completely understandable. You don’t lose patience with the character for doing it, as you sometimes can with a femme fatale—you know, when you see it coming three miles away. It’s also a character piece; it looks inside of a character who is without country, without a home. The whole story takes place in Tokyo.

HAMBURG: It’s difficult and expensive to shoot Tokyo.

BIGELOW: I’ve heard stories, but I’m optimistic. Shooting is never easy.

HAMBURG: Will this be the first time that work with a script you didn’t write?

BIGELOW: Yes. I’m thrilled. I really love Gibson’s world, and I love to be simply the translator and not necessarily put my stamp on it, whatever that stamp might be. I like to be just a conduit. That would be the ultimate objective on my part.

HAMBURG: I can’t wait to see it.

BIGELOW: I can’t wait to start it.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1989 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.