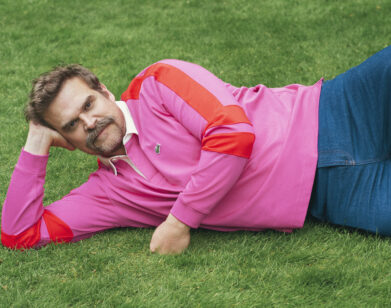

Mickey Rourke

In Bob Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles, Volume One, he recalls a trip to the movies he took in 1988 while recording his album Oh Mercy, when he went to see Mickey Rourke in Homeboy, a film about a small-time boxer whose passion and petulance prove self-destructive. Dylan offers this account of Rourke’s performance in the film, which the actor, a former boxer himself, also had a hand in writing: “He could break your heart with a look. The movie traveled to the moon every time he came onto the screen. Nobody could hold a candle to him. He was just there, didn’t have to say hello or goodbye.”

While Dylan might not be as revered a film critic as he is a songwriter, he is certainly onto something here. A lot of actors talk about being influenced by Marlon Brando, but Rourke is really the only one who practices a comparable brand of voodoo. Cool and combustible in Rumble Fish (1983). Indelible in Body Heat (1981). Magnetic in The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984). Dangerous in 9½ Weeks (1986). A Dylanesque antihero in Homeboy. Rourke seems to have a genetic predilection to stick his finger in the socket-sometimes in life as much as on the screen. Mickey Rourke: motorcycle loner; professional fighter; squanderer of talent; creature of cheap motels and ill-lit bars; a hundred miles of bad road. Mickey Rourke turns down Beverly Hills Cop (1984). Mickey Rourke says no to Pulp Fiction (1994). Mickey Rourke and Carré Otis in Wild Orchid (1990). Mickey Rourke gets arrested. Mickey Rourke gets back in the ring. Whether it was hubris or humility that drove Rourke to walk away from acting 17 years ago and resume the boxing career he began as a teenage welterweight out of Miami, only to return a decade and several concussions later with his hat in hand and little goodwill on his side, the fact remains that the film industry, despite its lack of anything resembling conventional wisdom, can sometimes show flashes of unwitting intelligence and allow a second act. Because actors like Mickey Rourke don’t come along once in a generation, let alone twice. So here’s round two, or is it 10, with the championship contender humbled, through the ringer, looking for one more chance, asking for another shot. And because it’s cheaper to buy low than to buy high. And because sequels are good business. And because everybody loves a good redemption story.

In Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler (2008), Rourke plays a onetime titan of the tights who now lives in a trailer park and, with a weakened heart and a body ravaged by years of flying elbows and steroid use, is out for some redemption of his own. Watching Rourke onscreen now—older, odder, beefier, his features more rugged from years of fighting and surgery-is actually strangely comforting, like some great wrong has been righted, even if the wrong in question was in part his own doing. He looks more physically imposing, but gentler in a way. He also seems somehow to have more power, some of it magic and some of it tragic, doing the kind of work he was meant to do, the kind of work people wanted him to do, the kind of work other people can’t do-at 56 years and numerous lives old, doing the best work of his career.

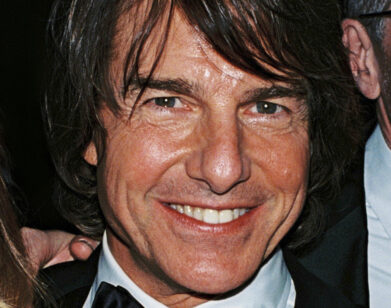

Christopher Walken, who has known Rourke since their days at the Actors Studio in the mid-’70s, recently caught up with him in New York.

CHRISTOPHER WALKEN: I wanted to ask you about growing up in Miami, because when I was a kid in the ’50s my father used to take us there. South Beach was where the inexpensive hotels were. Is that where you were? Collins Avenue near Wolfie’s coffee shop and everything?

MICKEY ROURKE: Yeah, yeah. It’s funny that you mention that, because when I was a kid and I was doing amateur boxing, Wolfie’s was right on the corner. So on nights that I’d be up really late and go to Wolfie’s, I’d see all of Angelo Dundee’s —fighters—like Muhammad Ali and Jimmy Ellis and Jerry Quarry, and all these guys would be there eating after they ran. They used to run on the golf course down there, and then they’d go to Wolfie’s and have eggs and shit.

CW: South Beach was where the cheap hotels were, right?

MR: Yeah, absolutely. They used to call it the Elephant’s Graveyard.

CW: In the ’50s, you could take your car on a boat and go to Havana . . . Anyhow, I’ve been reading some stuff about you that I didn’t know. I didn’t know you were originally from Schenectady.

MR: Upstate New York, yeah.

CW: And then you moved to Florida. And then you had your first career kind of in sports. And then you got into acting. Well, I never knew you were on the stage. What was it, a Jean Genet play?

MR: Yeah, I probably did a dozen plays, like Off-Off-Broadway stuff. And the Genet play was the first one I did. What the fuck was it? [pauses] Deathwatch.

CW: A lady got you into that? A teacher?

MR: You know what it was? It was actually a kid from my football team in high school who was going to the University of Miami. He was directing a play, and he didn’t like the leading man—or the leading man quit, or he fired him—and I was sitting on the beach one day, and he said, “Hey, man, I’m doing this play at the university.” I said, “Well, I’m not going to the university.” He said, “Yeah, but nobody will know it.” So he put me in the fucking play. And I liked it. I really liked it a lot. I had gotten injured during the boxing, and I was supposed to take several months off because I’d had a couple of concussions, and so I sort of just left the boxing and got into the acting by accident after I did that play.

CW: How much later was it that I met you at the Actors Studio?

MR: I would say maybe four years later. I think the first year and a half that I was in New York I was having trouble just living somewhere. Back in them days the city was a lot different than it is now.

CW: You know, I have to say that I recently saw The Wrestler, and you are great in it. It’s very difficult nowadays to get independent movies done . . . Oh, by the way, how’s your dog?

MR: She’s barking because I’m not paying no attention to her.

CW: Well, give her a pet or something. I had that on my list of questions. I was going to say, “How’s your dog?”

MR: Yeah, Loki’s still around. She’s 16½. I didn’t know you saw The Wrestler.

CW: I did. It is very powerful, and obviously they didn’t have a lot of money to spend.

MR: Well, it was really hard, because in the beginning, Darren [Aronofsky, the director] really wanted me to do it. I had done some research on him, and all the information I got I really liked. I asked some people who had worked with him whose opinions I valued, and everybody said, “He’s his own man.” But the thing with the budget was tough, because it was, like, a $6-million shoot. And then I was actually going to be replaced in the movie before we even started because they wanted a bigger name—Darren didn’t know if he could make the movie for so little money. So a couple of weeks later, after I got replaced, I got a phone call going, “You’re back in.” And after meeting Darren, I wasn’t jumping up and down excited, because I knew he’d want me to do, like, six months of weight lifting and put on an extra 34 pounds and then do three and a half months of wrestling training . . . And you know, it was one of them movies where you didn’t get paid. So I think my agent was more excited about the piece than I was. [laughs]

CW: Is the character based on somebody?

You know what it is? You get desensitized to getting hit. That’s where the damage comes in. It’s not the fights that fuck you up. It’s the decade or so that you spend sparring.Mickey Rourke

MR: It’s really based on all of the wrestlers from the ’80s, who pretty much went through that whole catharsis of transformation with moving from time to time and getting older and having to take performance-enhancing drugs to get bigger. And, at the end of the day, a lot of them walked away with no health care, no compensation for anything. They’re kind of like old shipwrecks by the end of their careers, in their early 40s, or late 30s even.

CW: I did a play once in Calgary, which is a wrestling capital, you know.

MR: Oh, I didn’t know that.

CW: And I stayed in this funky hotel where the bar was a wrestlers’ hangout. There were these huge guys—they were very nice. They were, you know, wearing jackets with fringe on them.

MR: Yeah, yeah. They’re a wild bunch. I didn’t realize the camaraderie that they have among them. It’s so unlike boxers, who are very isolated—or isolated within their own camps.

CW: You have a lot of experience with boxers behind the scenes. Is there a comparative thing between boxing and wrestling?

MR: You know, the two sports are as different as Ping-Pong and rugby. In boxing, you don’t know what’s going to happen. In wrestling, it’s already prearranged. But the thing I didn’t know about wrestling is that you really get hurt. Because, you know, you’re wrestling in front of a live audience, and you end up doing things like jumps or slams, and 40 percent of the time you don’t land right.

CW: And there’s an accidental elbow in the face or something like that.

MR: Exactly. So these guys are all pretty busted-up by the ends of their careers. Since I knew it was all choreographed, I thought, Oh, they don’t get hurt at all. But I walked away with a renewed respect for the sport. Because I was very ignorant before—I knew nothing about it.

CW: You know, there are maybe a couple of people in my life who I wouldn’t mind hitting with a folding chair.

MR: Exactly.

CW: Is that fun?

MR: Well, yeah, but sometimes you don’t get hit with the flat part of the chair. You get hit with the blunt part. And you get hurt.

CW: People make mistakes.

MR: Yeah. I mean, by the end of the shoot, my trainer was pushing me up three flights of stairs to my house and holding my arm like I was an old cripple. I had three MRIs in the first two months of working on the film. I felt like it really was over by the time we started shooting the movie.

CW: The actors love you. You know that. And you must be feeling that right now.

MR: Well, you know, look at it this way: I was pretty much out of work for 13 or 14 years, and toward the tail end of my sort of exile . . . I mean, I took the five and a half years off to go back and do the boxing, and then it was still seven or eight years before I started to work a little bit. [Steve] Buscemi gave me something to do in Animal Factory [2000] and then [Sylvester] Stallone gave me something in Get Carter [2000] . . .

CW: You were amazing in Sean Penn’s film The Pledge [2001].

MR: When I did Sean Penn’s movie, I think I was living in, like, a $500-a-month room, and someone called me up or bumped into me and asked me if I’d come up to work for a day. That sort of got me going a little bit. But it wasn’t until Sin City [2005] that I kind of got back into the game.

CW: When you were boxing, did you have real bouts with pros?

MR: Yeah. I had 12 fights—10 wins, two draws.

CW: Where?

MR: In Germany, Japan, Argentina, Oklahoma, St. Louis, Miami . . .

CW: The people who were watching you must have known you were an actor.

MR: Exactly. I tried to change my name for the fights, but the only way they could pay me money was if I used my own name. I wanted to change my name to, like, Romeo something-or-other, and they said, “No, we can’t do that. We’ve got to use Mickey Rourke.” Because they paid me a lot of money to go over to Europe and Asia to fight. I wanted to change my name to Romeo Florentino. But they didn’t go for that. Romeo Florentino—that’s a good fighter’s name.

CW: But they’re paying for Mickey Rourke—they want Mickey Rourke.

MR: Exactly. Not Romeo Florentino.

CW: So what was that like? The thing is that if somebody hit me—even lightly—I’d fall on the floor. That would be it.

MR: Well, you know what it is? You get desensitized to getting hit. That’s where the damage comes in. It’s not the fights that fuck you up. It’s the decade or so that you spend sparring.

CW: That’s how they say Ali got hurt.

MR: Yeah, it’s all that. Because I would spar an average of probably close to 30 rounds a week.

CW: You wore headgear, right?

MR: I wore it most of the time, but lots of times I didn’t. Then, I think it was around my 11th fight, I started having some memory-loss issues. I took a neurological exam, and they said, “Well, you should stop fighting now.” And I kept begging them for one more fight, one more fight, and the doctor said to me, “How much are they going to pay you?” I was supposed to fight three more times, and one would have been for a cruiser belt. So I said, “I just need to fight three more times.” He said, “Listen, you can’t even get hit in the head one more time, your neuro is so bad.”

CW: Well, I hope that’s over with.

MR: It’s been over with for 10 years now. I took a picture in Freddie Roach’s gym of me sitting in a rocking chair.

CW: There’s this story that Julian Schnabel painted a picture of you.

MR: Yeah. He painted a picture that he dedicated to my character in Rumble Fish. It was called The Motorcycle Boy. I remember when he brought it over to me at the Mayflower Hotel [in New York] years ago. This is when you and I knew each other.

CW: The Mayflower Hotel was the actors’ haven.

MR: It was the actors’ hangout. And I remember that he brought it over there one day, and I looked at it, and I couldn’t . . . I looked at it sideways, I looked at it upside-down, I kept looking for the motorcycle, and I couldn’t find one. It was some sort of abstract painting. But Julian and I have been friends for 20-some years now.

CW: Julian says that he has Marlon Brando’s boxing gloves.

MR: That’s right.

CW: But nobody’s ever seen them.

MR: He keeps wanting to give them to me, and I keep telling him to keep them.

CW: Well, you should take them.

MR: Yeah, but I have so many boxing gloves around my house that I would get them confused with other gloves.

CW: I was someplace doing a play, and I went to this auction where Muhammad Ali’s boxing trunks were up for bid. They were signed and everything. It was 1972, after the Vietnam thing had put him out of the business—you know, him not going into the Army. Nobody wanted these trunks. I got them for $40. Did I ever show them to you?

MR: No, I don’t think so. But I think we had a conversation about this once, because when I was like 12 or 13, Ali gave me a pair of his trunks that were white satin with gold stripes. They were full of blood, and my mother threw them away. I think it’s the first time I ever cursed at my mother.

CW: These ones I bought are Everlast. They’re black and white, and it says “The Real Champ: 1972” on them. And nobody wanted them because Ali was sort of off the radar. But come over to my house. I want to show them to you.

MR: I’ve got to tell you a funny story about Ali. I think it was around my seventh or eighth fight, and I got really nervous because I was fighting a pretty tough cookie from the Bahamas with a really good record. I couldn’t sleep at night—my hands were sweating, my feet were sweating—and I’d get up, and I’d start shadowboxing. I was a nervous, shaking wreck. So I called up this photographer I knew named Howard Bingham, who’d done books on Ali. I said, “Howard, can you do me a favor? Man, I’ve got this fight, and I’m a nervous fuckin’ wreck. Do you think I can talk to Muhammad Ali? I think he could calm me down a little.” This is, like, 10 or 12 years ago.

CW: Where were you?

When I did Sean Penn’s movie, I think I was living in, like, a $500-a-month room, and someone called me up or bumped into me and asked me if I’d come up to work for a day. That sort of got me going a little bit.Mickey Rourke

MR: I was in a hotel room in Miami. The next night I get a call, and it’s Howard Bingham, and he’s got the champ on the line. Ali didn’t remember me from being a kid, but he was going, “Yeah, you’re in bed, and you want your mama with you . . .” It really helped so much. He spent 15 or 20 minutes on the phone with me. That’s a memory that I’ll always cherish.

CW: I met Ali once, and you could feel that about him. He’s a very, very big spirit.

MR: I remember back in the day they called him the Louisville Whip. You’d hear him all through the gym, just running his mouth all day long. He’d yell at anybody who came into the gym.

CW: You wrote Homeboy, right?

MR: Yeah, I wrote Homeboy.

CW: Are you still writing?

MR: Well, I’ve been working on a script called Wild Horses for about 18 years now.

CW: I’ve heard about that. What’s it about?

MR: It’s about two brothers who haven’t seen each other for years, and they reunite for one last motorcycle ride.

CW: Actors like to direct sometimes. You ever think about that?

MR: No, I couldn’t direct traffic. [laughs]

CW: Exactly. People ask me about that all the time. They say, “Did you ever think of directing?” And I say, “It’s completely out of the question.”

MR: I’m on your side with that. It’s hard enough just acting.

CW: If I were directing and anybody asked me, “What do you think we should do?” I’d say, “Do whatever you want.” That’s not a good thing for a director.

MR: No, no, no. By the way, I saw an old mutual favorite director of ours recently. You know who I’m talking about, don’t you? It was great seeing him.

CW: I see him sometimes, too, and I miss him.

MR: I miss him working. Aronofsky reminds me a lot of Michael Cimino.

CW: It’s actually a mystery to me why he’s not making movies.

MR: I don’t know. Because, man, I’m telling you, on the floor he’s like a general. He brings the best out of you.

CW: Obviously, it’s his decision, because he’s perfectly capable of directing a film anytime he wants. Which brings me to Heaven’s Gate [1980]. That’s something we did together.

MR: I was so nervous working with you. I think you had already won your Academy Award for The Deer Hunter [1978].

CW: Just, like, a month before we started shooting. I was probably really obnoxious at the time.

MR: Well, you were actors’ royalty, brother. I mean, you were someone we all looked up to.

CW: No, I was probably a pain in the ass.

MR: Well, you were always, like, this strange being from another place.

CW: You know, we did that movie, Heaven’s Gate, and at the time nobody knew it was going to become this problem. Everybody was just having a terrific time. You and I have a scene in the movie. It’s at night. We go from the stable to Isabelle Huppert’s character’s house. We’re walking in the dark, and we pass some strange antiques stores. And I remember during the take, you said to me, “What’s that?” And I said, “It’s a flying saucer.” If you see the movie, and you listen very carefully, they forgot to take that out.

MR: There was something about outer space with you. You and I had dinner one night at the Outlaw Inn in Kalispell, Montana, and you said to me, “What do you think happened to all the dinosaurs?” I said, “I don’t know.” And you said, “I think they grew wings and flew away to another planet.” I always remind you of that, and you never fess up to it-that that’s the conversation we had.

CW: But you did remind me of it. There is a scene like that in Homeboy.

MR: That’s why I wrote it. Because I thought, Wow, here I’m having this one chance to have dinner with one of my favorite actors in the world, and he’s talking about dinosaurs in outer space.

CW: There was this story that I heard, something about me teaching you to put on makeup. It rings a bell, but . . .

MR: When I was really young and I got into the Actors Studio, I used to see [Robert] De Niro and [Al] Pacino and [Harvey] Keitel and you, and you were the one who was most available, believe it or not. You spent a lot of time with the other actors. I think you really liked it there. So I remember you and I had a conversation one time, and you said to me at the theater that you always did your own eyes. So after you told me that I went out and bought some fucking makeup kit, and I did my eyes. Then, five years later, I finally got a job-I think I went out on 78 auditions before I ever got a fucking job. I think the job was Diner [1982], actually. And I insisted on doing my own eyes. The DP actually pulled me aside one day and said, “Listen, we’re not doing Dracula.”

CW: That’s because I grew up in Broadway musicals, in the chorus, and in that world we did a lot of our own eyes. I carried that into movies, and it was a huge mistake. It took me decades to get over it.

MR: Yes, I often looked at your eyes in movies. You have very heavy-lidded eyes anyway.

CW: The eye advice was not good.

MR: Yeah. If you look closely at some scenes in Diner, my eyes look like Dracula’s. But the DP got me to stop that, and I was a little pissed off because I’m thinking, My God, if Christopher Walken tells you to do your own eyes, then you’d better fucking do your own eyes.

CW: This was my mistake. I’m sorry. So you’re living back in New York now?

MR: I lived in London and in Paris for a while. In London, I’ve been staying at the same hotel for, you know, 20 years. In the same room.

CW: I’m always looking the wrong way there when I cross the street. But you like it back in New York?

MR: I love it. This is where you and I met. This is where it all started. It kind of all started for me in the West Village, and it’s probably where it will all end for me.

CW: I spent so much time there that I like being out of it.

MR: Are you living out in Connecticut still?

CW: Yeah. If you’re ever taking a drive, come see me.

MR: I remember many, many years ago, I was at your house. We were with that guy, Lenny, and he was looking for a bottle of wine or something, and he looked in your cabinet, and he found your Academy Award mixed in with the booze.

CW: Well, I’ve got this little room now where I keep all sorts of those things. But I remember, yes, I had just had all this gravel put down, and we were -standing outside, and you said to me, “Good gravel.”

MR: You did have an awful lot of gravel in the front yard. Have you been back to the Actors Studio at all?

CW: Hardly. Though about a week or two ago I was in the neighborhood, and I just dropped in. It’s good, because it’s sort of the same, except it’s got fresh paint on it. It was on an off day, and there was nobody there. The place was clean and painted. But it still looks the same.

MR: We had some characters there back in the day.

CW: We did. It was funkier.

MR: It was like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

CW: A little bit. Remember the director sessions, where they used to attack each other?

MR: Yes. It depended on who was moderating. When Shelley Winters moderated, I usually went out and smoked a cigarette. She had that screechy, kind of nails-on-the-chalkboard voice.

CW: Listen, it was a great place to meet girls.

MR: Yeah, well, I never saw you with any.

CW: Well, I used to follow them out.

MR: I just used to follow Al Pacino and you out. And Harvey Keitel. I didn’t give a fuck about the girls. I just wanted to see which way you guys were going.

CW: So you’re going to be busy for the next while.

MR: Yeah. You went through this, right?

CW: Well, it’s a wonderful thing. You made something really beautiful, and maybe that’s even more important than awards. Thirty years later, you’re one of the top actors doing important work, and that’s very powerful. You know, there’s an old saying: “Nothing happens ’til it must.” I like that.

MR: Let me ask you one question.

CW: Yeah.

MR: Where did the dinosaurs go?

CW: They’re sitting in the tree outside.