director

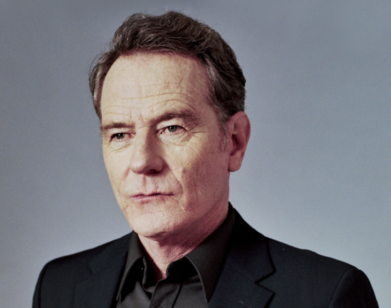

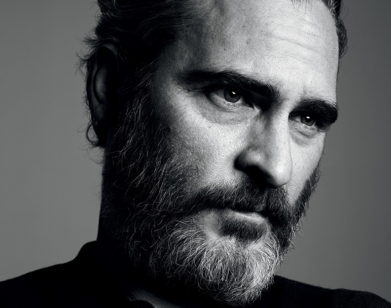

M. Night Shyamalan and Bryan Cranston Probably Won’t Read This

There isn’t much to say about the new M. Night Shyamalan movie on account of it being, well, a new M. Night Shyamalan movie. But if you happened to catch the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it teaser that aired during this year’s Super Bowl, then you know that the famously secretive director’s latest thriller, Old, has something to do with a group of people stranded on a tropical island that causes them to age at warp speed. (The“why” of it all will likely be uncovered in one of his trademark twist endings.) The movie, which was shot in the Dominican Republic during the opening months of the pandemic and features an ensemble cast that includes Gael García Bernal, Vicky Krieps, and Thomasin McKenzie, marked a rare departure from the 50-year-old filmmaker’s beloved hometown of Philadelphia, where his films are typically set, and where he established Blinding Edge Pictures—mission control for Shyamalan’s creative empire. It was from there that the director, in between putting the finishing touches on Old and filming the third season of his Apple TV+ series Servant, caught up with his friend, Bryan Cranston. —BEN BARNA

———

BRYAN CRANSTON: Hey, man. How are you?

NIGHT SHYAMALAN: I’m good, buddy. A little crazed. I’ve been thinking about how in almost any career, but mostly artistic ones, they go up and down, up and down. And the things you’re willing to do when you’re at the bottom are the things you let go of the second you’re at the top, because the trappings of success are the opposite of the things that got you there, and you stop doing those things, and then the descent starts again. I’ve been wanting to watch La Strada for six weeks now. But my life is such that I can’t go and watch a Fellini movie. I’m too busy making things. That’s a long-winded answer to your question.

CRANSTON: Let’s talk about that. You’re very prolific. You seem to come out with a movie every other year. You’re working continuously.

SHYAMALAN: And because the movies are, to a great extent, sold on my name, I’m doing what you do. I go and promote the movie in every country around the world, and then I go back and become a writer by myself for six months, which is much needed at that point.

CRANSTON: Do you have a list of story ideas that you pull out and say, “Okay, here’s the next one that I’ll start as soon as I’m out of post-production on the other one”?

SHYAMALAN: The answer is yes, but that’s not always been the case. I’m three ideas back, so in theory, I know my next three movies.

CRANSTON: Something I’ve been feeling is that when you’re blessed with great fortune and good opportunities, you work like crazy. For the last 20 years, I’ve had a mega amount of opportunities, and I’m deeply grateful for that. At the same time, and I’m sensing the same from you, if you’re so busy working, is your life basically on hold? You can’t watch La Strada. I can’t read a book if it doesn’t have anything to do with the next film I’m doing. I haven’t read a book for pure joy in so long. When’s the last time you traveled just for the sake of the experience, not connected to promoting a film or scouting locations?

SHYAMALAN: I want to put some nuance into what I said earlier. I read a book a week that has nothing to do with the movies that are being offered to me. I can’t be a writer if I’m not doing that. With travel, as you know, I just make everything here. I’m shooting Servant 25 minutes away from where I’m sitting, and we’re editing Old upstairs. I literally go up the stairs and I’m making movies. I’ve made my life so that I’m at dinner with the kids.

CRANSTON: Your choice to stay in and around Philadelphia has to do with familial responsibilities. When your kids are grown and out of the house, will you stay close to Philadelphia or stretch out and try some different locations?

SHYAMALAN: Old was the first time that I didn’t start a script with “Exterior, Philadelphia.” When I started the script, it was, “Exterior, Beach, Unknown Island.” That’s because the kids are older, and I told them two years in advance, “In two years, I’m going to go shoot a movie where I can’t be in Philadelphia, so you guys are going to need to go there with me, and our lives are going to get disrupted. Is that okay?” And we went, and it was a beautiful experience.

CRANSTON: Without giving it away too much, what is the main theme of Old?

SHYAMALAN: It’s about our relationship to time and what you would do if you realized you were going to spend your whole life in one day on a beach. What would you say? What would that feel like? You’d be terrified at first, but what’s important, given that context?

CRANSTON: I was struck by finding out that you’re now 50. The wunderkind is now a senior citizen. Has your perspective adjusted somewhat now that your kids are growing and you’ve been on this planet for a while?

SHYAMALAN: Certainly. If I could go back and do things over, I don’t know if I would undo my mistakes, but I would want to undo my weighting of those mistakes. If I could go back, I’d talk to the 29-year-old who did Unbreakable, and who was lying down on the sofa, depressed, on Thanksgiving weekend, because How the Grinch Stole Christmas beat us. I had made something that was so representative of my cinematic tastes, and I felt rejected. I would tell him, like I tell my daughters now, “The singularity of your voice is the thing you have to offer the world. It mayor may not be accepted at that moment.” We can tell when an artist compromises to fit the mores or the values of the time, and it dissipates and reduces their power. In the case of Unbreakable, well, you and I, walking down the street, would definitely run into someone who would say it’s their favorite movie. But I’m still terrified. We don’t get to skip that part, even after success.

CRANSTON: Really?

SHYAMALAN: Yeah, dude. I made The Visit, which was a comedy horror and very odd in tone. I kept wondering, “What are people going to think?” Luckily, that movie found its audience. Same thing with Split. I was like, “Is anyone even going to understand this?” There are so many foreboding things in that movie. Girls getting abducted, girls getting eaten, flashbacks to a molestation. I was like, “What am I thinking?” I feel that every timeout, but I try to remember the 29-year-old kid on the sofa who made Unbreakable and felt like he had done something wrong.

CRANSTON: You’re a guy who has received Oscar nominations and Razzies. Talk about the ups and downs of life. Does it affect you? Does it put a chink in your armor when you get a bad review? I don’t read reviews of my own work for that very reason. The good reviews are kind of blowing smoke, and the bad ones are the ones that can get into your soul and start corrupting you.

SHYAMALAN: I’m exactly the same way, Bryan. I don’t read anything about me in any way. I get the general gist of what’s going on, if it was well-received or not, but we want our relationship to our material, to our characters, to be the thing that we obsess about. If we start to think about reviews, we’ll start to calculate and be safer. I want to have the courage and strength to do what I’m saying to you. I have, at times, been good at it. I so desperately want to be accepted by everyone. I want to be liked, I want to be admired, but it has to be me. I want you to like me, Bryan. I really do want you to like me.

CRANSTON: I’m sorry. I just don’t think that’s going to happen.

SHYAMALAN: [Laughs] But it has to be all the weirdness of me that you like.

CRANSTON: Have we seen all the weirdness of M. Night Shyamalan in your films?

SHYAMALAN: You haven’t. My instinct is to be provocative and weird, and I think I’ve mitigated that, but the sweet spot of the audience has shifted in a way that’s more in alignment with me, ironically. If I have another movie that opens number one in this decade, this will be the fourth decade that a movie of mine has opened in the top spot. I believe that’s because the tastes are actually more in alignment with my weirdness.

CRANSTON: You mentioned Servant. You’ve only been in the feature film business, and now you’ve gone into the serialized storytelling business. How is it different for you?

SHYAMALAN: It’s a format that I have a problem with, and the reason is, with the exception of a handful of shows, and Breaking Bad is one of them, you can’t maintain the quality level from beginning to end. That is not an indictment on the artist. The ratio of resources and time, to the amount of material you have to deliver, is untenable. The Breaking Bad’s are so rare because that equation is so hard to do, so I was terrified of it. To make it easier on me, I waited until material came that made me go, “Oh, I see how I can do this.” Servant is told in half-hour episodes, and it’s essentially a play. It’s all in one location. We built the house 25 minutes from here. We go and we shoot there. I can work with all the writers myself and talk them through everything. And then I said to Apple, “I think I can do this for another year after this.” And during the pandemic I wrote it out and I said, “I think it’s 40 episodes.” For that story, I feel comfortable being able to do it for that amount of time. Normally, as you know, you don’t even know if you’re getting renewed. You don’t even know if you’re going to get a chance to finish the story.

CRANSTON: When you have a story and you write it out, you also storyboard it. Is it true that you storyboard your movies shot by shot?

SHYAMALAN: Yeah. Even if you watch Servant, at least the episodes I’ve directed, I can show you every single shot frame-by-frame. It’s something I’ve trained in since I was young, which is super unusual, and it seems crazy and restrictive. However, I think of it as a slightly different art form. I’m imagining it so specifically—why we’re moving the camera, who we’re not showing, why it’s over your shoulder and coming around and waiting for your decision to be made. I can tell you why I thought of all of those things in that moment that your character makes that decision, to enhance the characters’ emotions and to give a consistent vocabulary, a visual nomenclature, for the audience to master. It gives each movie a specificity. In Old, you’ll see a lot of angular dollies on the beach, creating geometric movements in an ambiguous space, and I could go on about why I did that, but I’m not going to be able to spontaneously think about that at 100 miles per hour on set.

CRANSTON: You used to make Super 8 movies. Steven Spielberg, who also did the same thing as a child, is now doing a movie about a young boy who picked up a camera and started telling stories. Would you ever write something that has more of an autobiographical sense to it?

SHYAMALAN: It sounds strange, but that’s what I’ve been doing. Because I write my movies, they naturally are about my life. The children in my movies reflect the ages of my actual children. A movie called Old is about my relationship to my children becoming adults, and parents becoming very, very old. I go over to my dad’s house, and I’m not sure he’s aware anymore that I’m famous or successful. I don’t think it registers for him. He sees me come through the door and he sees his son again. But he still senses my weight. He’s like, “You seem upset. What are you upset about?” And then I’ll say, “I’m making a movie, and I’m just thinking about it.” And he’s like, “It’ll be okay,” and we have that moment. This movie is about how fast this all happens. My dad was taking care of me, and now I’m taking care of him.

CRANSTON: It’s the circle of life. Speaking to that, you were born in India. How old were you when you came to the United States?

SHYAMALAN: Essentially, my parents were here, went back to India, and had me there to be with family. I was only there for a few months.

CRANSTON: How do you feel about your country there and your country here? Do you feel a natural gravitation toward India and the relatives you have there? And I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the terrible pandemic that’s happening in that country now. Can you shed any light about your perspective on it?

SHYAMALAN: Being an immigrant filmmaker, the amazing thing is that I’m now thinking about it because the culture is thinking about it. As a kid, I ran from it. And then, as a young adult becoming known in the world and in the United States, I was confused about my place in all of it. I always felt like a fish out of water. I’d be at an event with directors, and every single one was not my color. I’m telling American stories, but tinged with Eastern influences and thoughts and spiritualism that I’ve fitted into genre. One of my great joys was when I went to the White House and President Obama introduced me to the prime minister of India and said, “This is one of our favorite sons who’s actually Indian.” Obviously, it’s a place I feel very connected to.

CRANSTON: Have you ever directed something that you did not write?

SHYAMALAN: In Servant, there were episodes, but my genetics were there to begin with. I haven’t yet. Normally, people come and ask me to write and direct an idea. I’m certainly open to it. I’ll tell you what, though. Because I didn’t write those Servant episodes, I was a very different director. I was able to have that little bit of detachment that allowed me to see things clearer than in my movies, because I can’t separate my movies from myself.

CRANSTON: Let me ask you one last question. When you write and direct your own films, do you feel that you are insulated, and that you may be missing a perspective that, if you had just directed, you would gain?

SHYAMALAN: Wow. That’s a big last question. The thing I find so tortuous is that I’m simultaneously trying to make my own movie and make a movie where I say “I see you” to the audience: “You came and you need this, and this is a contract of entertainment. And I love that and respect that and I see you and I want to be in your hearts and connect with you and have you have this experience.” I’m trying to do those two things together, so they see me, and I see them. It’s a very tricky balance, but it’s one I believe in. I believe that we can see each other when we tell stories.

———

Grooming: Kumi Craig