The Respectful Medium: Ken Loach’s Kes

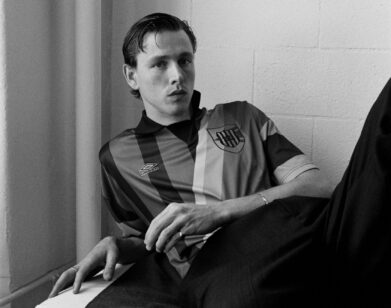

DAVID BRADLEY IN KES.

Where society fails, filmmakers step in. This is one way to view Kes, Ken Loach’s landmark film from 1970 about a working-class boy in northern England and the bird that gives him wings.

Billy Casper (David Bradley) lives in a fatherless household with his nasty brother (Freddie Fletcher) and inattentive mother (Lynne Perrie); at school, he is berated by teachers and picked on by his peers. It’s not that people are inherently mean; particularly in its school scenes, Kes inculpates a system that is callously indifferent to the drives and desires of boys like Billy. His gym teacher, not fully evolved himself, calls him an “ape,” and a teacher snarls that Billy has “just come out from under a stone.”

Nowhere is there any evidence, however, that the community to which these authority figures belong expects him to be anything but a primitive who will soon be joining his brother in the local coalmines. The only difference between school and the job he imagines he’ll eventually ends up taking, Billy explains to an uncomprehending employment officer, is that “I’ll get paid for not liking it.” One of Billy’s teachers (Colin Welland) sees something more in him, and goes out of his way to watch Billy fly the kestrel that the boy, armed with nothing more than a stolen book on falconry, has remarkably trained himself. Otherwise, the people showing Billy any compassion are Loach and his collaborators.

In the 45-minute “making-of” documentary that accompanies Criterion’s new Blu-Ray reissue of Kes, Loach explains how “observation” is the governing concept behind his filmmaking. He doesn’t meddle with or force a story, and says he treats his blue-collar film subjects with the respect he would accord them in real life—no bright lights or intrusive close-ups. Loach makes the interesting point that there’s something inherently critical in contrast lighting. In order to let the characters come alive, Loach posits, “You just give them space to be who they are.” To be sure, the long and long-medium shots of Billy swinging a lure for his swooping bird tug at your heart in a way that a well-lit close-up never could.

Even by the hands-off standards of documentary filmmaking, Loach and his collaborators—his producing partner, Tony Garnett, and the primarily non-fiction cinematographer Chris Menges—have a gentle touch. (Compare the loose, episodic style of verité storytelling on display here to the taut narratives of Belgium’s celebrated Dardenne brothers.) And it’s nice that Barry Hines, who wrote both the screenplay and the novel it’s based on, didn’t take the easy route and imagine his young hero as a crowd-pleasing artist, à la Billy Elliot. (“Wrong kind of bird,” Garnett recalls being told by the countless U.K. movie companies that turned down Kes before United Artists backed it.)

Loach learned some of his techniques from Jean-Luc Godard, and had surely seen Francois Truffaut’s less sentimental (but also very successful) tale of a disaffected boy, The 400 Blows. His and Garnett’s most direct source of cinematic inspiration, though, was the roughly contemporaneous Czech school of Jiri Menzel and Milos Forman, which they found more authentic than the “angry young man” British dramas of the sixties. Those films often featured stage-trained London actors trying on rough accents. But apart from Welland, no one in the Kes cast was a full-time actor—certainly not Bradley, whose tenderness and uncertainty have less to do with his lack of acting experience than with his character, a young survivor who has “begged, borrowed, skived, and scrounged,” in the words of a disgusted teacher, and has taken no pleasure in any of it.

A keystone of the film, and of its politics, is the idea that there is human potential everywhere—and that society is set up, for the benefit of a privileged minority, to keep large veins of it untapped. Appropriate, then, that the casting process of Kes gave a group of Yorkshire folk accustomed to fewer options in life a larger sense of their talents.

KES IS OUT ON CRITERION BLU-RAY AND DVD TUESDAY, APRIL 19.