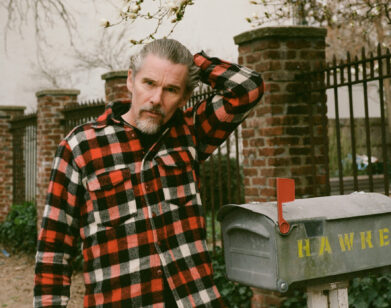

director

Ken Burns and Isabel Wilkerson on Finding Hope in History

By the time this story publishes, one of the most tumultuous chapters in American history will have come to an inglorious end. Its lasting effect can’t yet be fully grasped, and how future generations will process it remains to be seen. But even Ken Burns, who has devoted his life to excavating and examining the story of America, was shaken by how close it came to the brink. At the age of 67, the Brooklyn-born filmmaker has cataloged this country’s triumphant moments and wrenching defeats, its significant accomplishments and dangerous impulses. He has shone a light on its forgotten heroes and resurrected its archvillains. Take, for instance, his first film, 1981’s Oscar-nominated Brooklyn Bridge, a story about unparalleled ingenuity and collaborative spirit that announced Burns as a major filmmaker. Or his nine-part saga The Civil War, a sweeping yet meticulous look at America’s capacity to devour itself, which established him as a singular one. Or 2019’s Country Music, a 16-hour odyssey into the soul of America, which grapples with the genre’s complicated racial legacy while also lionizing its heroes. His filmography reads like a syllabus of the American experiment: The Congress, Baseball, Thomas Jefferson, Jazz, The War, Prohibition, The Central Park Five, Jackie Robinson, The Vietnam War. No one but Burns, with the help of his trusted and frequent collaborators, like the writer Geoffrey Ward and his co-director and producer Lynn Novick, could have made them.

Burns has said he wakes the dead, a reference to a conversation he once had with his father-in-law about the death of his mother when he was a child. “Look what you do for a living,” his father-in-law told him. “You make Abraham Lincoln and Jackie Robinson and other people come alive. Who do you think you’re really trying to wake up?” His latest film does just that. Hemingway, which was co-directed with Novick, is a three-part, six-hour portrait of the American literary titan that uses all of Burns’s trademark techniques—the narration from Peter Coyote, the starry cast of voice actors (Jeff Daniels plays Ernest Hemingway, and Meryl Streep, Keri Russell, Mary-Louise Parker, and Patricia Clarkson his four wives), and what has become known as The Ken Burns Effect—his ability to enliven still images by slowly panning across and zooming into photos—to bring its subject to life. Shortly after the presidential election, Burns got on the phone with another chronicler of American life, the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author of last year’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Isabel Wilkerson, to try to figure out the strange impulse to move forward by looking back. – BEN BARNA

———

KEN BURNS: I should say at the top, it’s a funny upside-down world, because in many ways, I should be interviewing you. The Warmth of Other Suns is one of, if not the most important nonfiction book of this century so far. And you’ve just written Caste, which has totally recast how we think about so many things.

ISABEL WILKERSON: I really appreciate that. I’m someone who goes deep in the work as you do. And I’m speaking to you from the perspective of someone who feels as if I’m on a parallel journey of trying to understand and train a light on aspects of our country that not enough of us see. I wanted to ask you about your balancing effort, between the time it takes to produce your masterpieces against the urgency of your mission. How do you manage that inherent tension?

BURNS: There is an incredible urgency. And yet, there’s also another governor on my engine, which is to get it right. In a funny way, that tension is the engine of the work itself, and you can’t abandon any aspect of the process in order for it to have the depth, to not just be something that floats on the surface. There’s got to be dimension and echo and contradiction and dissonance. Not because you’ve intentionally put it there, but because the world is like that.

WILKERSON: There’s a kind of melancholy that I feel in your work, a quality of what might have been, and of what we can learn from what has happened, and how we can do better. Is that fair?

BURNS: I think that almost all of the stories you and I tell are informed by the imperfect human beings who have an all-too-short passage on this earth. We spend most of our lives avoiding the reality that none of us get out of here alive, and do all sorts of distracting things, good and bad, to just not deal with it. And so I think that when you have been—as I have been—beset by loss early on, you know that’s the end of every story. So I do think that my work is diffused with a sense of loss.

WILKERSON: With all that you have done in your work, thinking deeply about our country and its origins and what we’ve survived and what we have yet to do, how are you looking at this moment, now that we’re on the other side of the election?

BURNS: I haven’t been able to process it very well, because I’ve been so fearful. Even in my studies of the Civil War, I have never felt the fragility of who we are and the potential mortality of this experiment, flawed as it is, like I do now. Nonetheless, I’m invested in, as President Obama says, the notion that we’re always moving toward a more perfect union. We have what I call the three viruses. Obviously the scientific one, which has kept us locked down and changed our habits and rearranged our society so drastically. There’s also the 401-year-old virus that has beset our country, and that continually plays out in every film that I’ve done. And then there’s the virus of this new age, where we have found that the very agents of our deliverance of information have come back to conspire against us in a way that certain things don’t matter. That we found that facts aren’t important, that we are tolerant of the counterfactual, that we revel in it. That we understand that if my enemy is disturbed by it, then I need to say it even more. And that has threatened our institutions. It has threatened our daily life. It has threatened the comity that has normally connected us at a basic level, and, on a larger scale, our national identity.

WILKERSON: When you approach the work with a sense of comprehensiveness and mission, you’re hoping to open minds and hearts, and you’re hoping that somehow you can be that bridge. I think about how your first film [the 1981 documentary Brooklyn Bridge] was about a bridge. I wondered what your thoughts are now that these ruptures are so visible to us, now that 73 million people voted toward a divisiveness that has been so damaging to our country. I think about all of the work that you’ve done, and the work that I have done, in seeking to build those bridges. I happen to be the daughter of a literal builder of bridges. My father was a civil engineer, so I know of no other way. The goal of the work is to be able to allow us to see how much more we have in common than we’ve been led to believe. We all are inhabitants of this old house, and we didn’t build it, but we are its current occupants. So I wonder, when you spend as much time as you have in telling this story and hoping that it will open minds and hearts, how do you look upon the current era where so many people seem not to see it? And how does that affect your work going forward?

BURNS: It’s sort of like being in a game and you’re down some points. I don’t have any other gear except this gear. I live in rural New Hampshire, and there are people all around me who cast a different vote than me, and I have tried to keep an open mind about their humanity, and I’m in close contact with their humanity. If I’m in a ditch, they’ll pull me out. So I am encouraged by the fact that if you just keep your head down and do what you’re supposed to do—and what you’ve been told, in my case, that you’re pretty good at—then there’s only one gear you can have and that’s forward.

WILKERSON: At a time like this, how does one measure one’s efficacy in reaching people? How do you measure it?

BURNS: Well, it’s interesting. I still get actual letters from people who have to find out where I live, write on a piece of paper, put it in an envelope with a stamp, and drop it in the mail. And I get hundreds of letters. They want to talk about a relative who played minor league baseball, or an older brother who was killed in Vietnam, or a great-great-grandfather who fought in the Civil War. And there’s a kind of passion for the very thing we’re so worried that we’re losing, which is the connection to one another. I’m always drawn to this statement that the novelist Richard Powers said: “The best arguments in the world won’t change a single person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” So I can argue until I’m blue in the face, but the only thing I really have at my disposal is a lifetime of trying to synthesize these complex American stories and reflecting them back to us. And that has to do with the kind of emotional archeology that I’m interested in pursuing that isn’t sentimental or nostalgic, but is interested in tapping into, as you do so well, the higher emotions that get released by art, by freedom, by the liberation of the human spirit. That’s all it’s about for me. The dates and facts and events mean absolutely nothing. They are shards of some piece of pottery, but it’s the emotion that reforms that pot, that carries the people who serve food in that pot across the room. It recreates the houses that they lived in and the villages or the cities or the empires that they were a part of. And that’s why I don’t just merely retreat to the safety of a rational world, where one plus one is always two, but instead look for those moments which our faith and art and reason and literature and love can direct us to. And in that case, one plus one equals three. I’m interested in that improbable calculus, full stop.

WILKERSON: When people ask me the theme of my work, I say that it’s love. Even though people might see melancholia, some see sadness, some see tragedy, I see love. What do you see in what you’re doing?

BURNS: It’s the only equation in the universe that makes any sense. After the election, I pulled out my lawn sign and I replaced it with one that says “Love Multiplies.” That’s the only thing I have.

WILKERSON: Which brings us to your latest film, Hemingway. His story is so layered and adventurous and tragic, but how is it that you chose to focus on him?

BURNS: We’ve been talking about him for a long time, myself, Geoff Ward, and Lynn Novick. You mull it over, you begin to explore, you begin to read, and you begin to understand what the contours might be. But once we say yes, it’s a yes without fully knowing. And then it’s a process of discovery. Somebody once told me that all history is failure. All biography, particularly, is failure. How could it not be? How could you possibly pretend to go back a century and understand a person? It’s an impossible task, but as human beings, we’re kind of obligated to do it. Whatever preconceptions I had have now been obliterated. Whatever sense I’d had of being able to easily grasp this human being has been completely blown apart. His first wife Hadley [Richardson] said that he had so many sides to him, so many facets, that he defied geometry. And that makes it a seemingly impossible task for biographers. But if you give it enough time, something can accrue.

WILKERSON: What are some of the things that you discovered?

BURNS: We came to find out that he did something impossible in the middle of modernism that was a priori complicated: He made it incredibly simple. Miles Davis didn’t have the chops to play like Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie, but, boy, whatever he did play was perfect. One of our consultants, Stephen Cushman, says on camera that the simplicity that Hemingway dared to have had was really as complex as Faulkner or Joyce. He wanted it to be accessible to everyone.

WILKERSON: How long did this film take to create from start to finish?

BURNS: It’s been several years. For the last two years or so, we’ve been in the editing room trying to make sense of all of it. At first, it was going to be a one-off. And then we instantly knew it would be a two-part thing. And very early on in editing, we realized, “Oh my goodness, it’s three.” A lot of our work is just structurally rearranging the goalposts and the arcs of the individual episodes so that they can merge as one long continuous narrative. And that is hugely complex to try to master.

WILKERSON: What was your first exposure to Hemingway as a reader?

BURNS: I’m really a prodigal child here. I began as a teenager, aspiring to be a writer or a poet, and the first short story I read was The Killers. And then I read a couple of other short stories. Then I moved on to novels, and I found that at the foot of my bed was a volume of the collected short stories that would, of course, include the five or six masterpieces, which anybody can read in just a few minutes at any time: The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber, Up in Michigan, Indian Camp, The Killers, Hills Like White Elephants, and most of all, The Snows of Kilimanjaro. I find myself in different periods of my life saying, “My favorite is The Sun Also Rises. No, it’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. No, it’s The Old Man and the Sea.” And then I finally just go back to the perfection of those short stories, with this impossibly young man having decoded something essential about how to communicate with words.

WILKERSON: I’ve found that there are so many things that were astonishing about him. He was someone who created his own mythology, and then the tragedy was the stress of having to live up to it. I hadn’t realized he’d had nine concussions, that it felt like there was almost an inevitability of tragedy. How did you manage what we already know versus what you were discovering, and what you wanted us to know?

BURNS: That’s a hard thing to do. For years, Geoff and I talked about this as a film that begins with a gunshot and ends with a gunshot. His father’s suicide and, I don’t think I’m ruining it for people, Ernest Hemingway’s suicide. But his father’s death takes place a third of the way into our film. And that meant that we had to acquire a whole new set of understandings about Hemingway’s life. I think that’s the simplest answer to that question.

WILKERSON: When I approach something, I almost have to feel a personal connection to the subject, or I can’t get inside their mind and heart to truly understand them. I wondered if that is the same for you. What connection did you feel to him or to his life story?

BURNS: There are some horrible aspects to him, and yet there’s something very compelling about him. I didn’t realize until deep into [the 1998 documentary] Frank Lloyd Wright that I really didn’t like Frank Lloyd Wright at all, but his genius overwhelmed everything. You just had to suck it up and say, “Okay, he’s impossible, he’s egomaniacal, but here it is.” Hemingway doesn’t have a lot of those barriers. He does some pretty horrific things, but he has an honesty about who he is that predicts and foretells all of these things. I guess I would have to say that I don’t have to like them or love them. We’re all in pursuit of happiness, all looking for a more perfect union. It’s about the process, it isn’t about the destination. Nobody arrives there, ever.

WILKERSON: Are there particular challenges to telling the story of, say, an epic phenomenon like the Civil War or jazz or baseball or country music, as opposed to a singular life? How do you approach the work when you’re choosing one massive phenomenon versus an individual?

BURNS: I wish that I could give you some perfect kind of formed idea about how we choose them. The simplest and glibbest answer is that they choose me. I’m just looking for a good story, and you don’t think about it in terms of scale. You think about the daily work. To me, it’s all hard. I’m sure there were 10 million problems in making The Vietnam War. And there were at least a million in Hemingway, all to be overcome. It’s overwhelming, but you get up and you go day by day.

WILKERSON: I think of them as thousands of decisions that have to be made. If you think of it as one big thing, then you would never even begin it.

BURNS: If we dwelled on our mortality, we could be reasonably forgiven for lying in a fetal position sucking our thumbs, but we don’t. We get going and get started with whatever time we’re given and try to do our best. As I’m sure you do, I feel like I’ve got the best job in the country. It is incredibly hard, it’s seven days a week, it’s hugely demanding, and I’ve been doing it for more than 30 years, and would have it no other way.

WILKERSON: I was wondering if the existential crisis the country has been experiencing has affected your thinking about the priorities that you set for the projects that are yet to come. Have you thought about moving some things up or putting a little bit more emphasis on something?

BURNS: What’s been going on with this pandemic of 401 years of racism in the United States hasn’t changed. It’s just been made more manifest this year. So there is a sense of adding more projects just to accelerate the ability to communicate both the singularity of these moments and also their place in a continuum. George Floyd was not the first Black person to be murdered by the police, and he’s not the last.

WILKERSON: Not at all.

BURNS: This stuff has been going on for a long time. Back in 1992, when Rodney King’s beating was filmed, people were talking about it as if it was the first time this had ever happened. I went and got out my books on lynching and I said, “This happened in 1888. This happened in 1914. This happened in 1990.” I’ve got a project on the Civil War that I’m hoping to accelerate, but not in an artificial way.

WILKERSON: Not in a reactive way. Don’t you think that with the work that we do, you’re reaching for a higher truth that prevails regardless of the time or the moment we happen to be in? I don’t like to think in terms of moments. I like to think about the enduring truth of history. I often say that history is only news if you haven’t known it before. So I’m wondering what your thoughts are on the universality and timelessness of the work that we do.

BURNS: That’s exactly right. Lets just remember that time itself is an artificial, human construct. We spend a lot of time talking about history repeating itself. History has never repeated itself. You’re not condemned to repeat what you don’t remember. Mark Twain is supposed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” If he did in fact say that, if anyone said that, that gets closer to what it is. Ecclesiastes says that there’s nothing new under the sun. The implication is that human nature doesn’t change, and it is present in the random sequence of events. We can foresee the themes, we can perceive the motifs, we can perceive recurrences of certain behaviors, but there’s no repeating. So there is nothing new under the sun, and yet, as you said, the only thing that’s really new is the history you don’t know, because that history, and being aware of those patterns, being aware of that rhyme, knowing those epic verses, prepares you for a present. And if you’ve got one as challenging as this present, for all the melancholy, for all the sadness and loss that may permeate the story, it can make you hopeful.

———

Photography Assistant: Kenyon Anderson