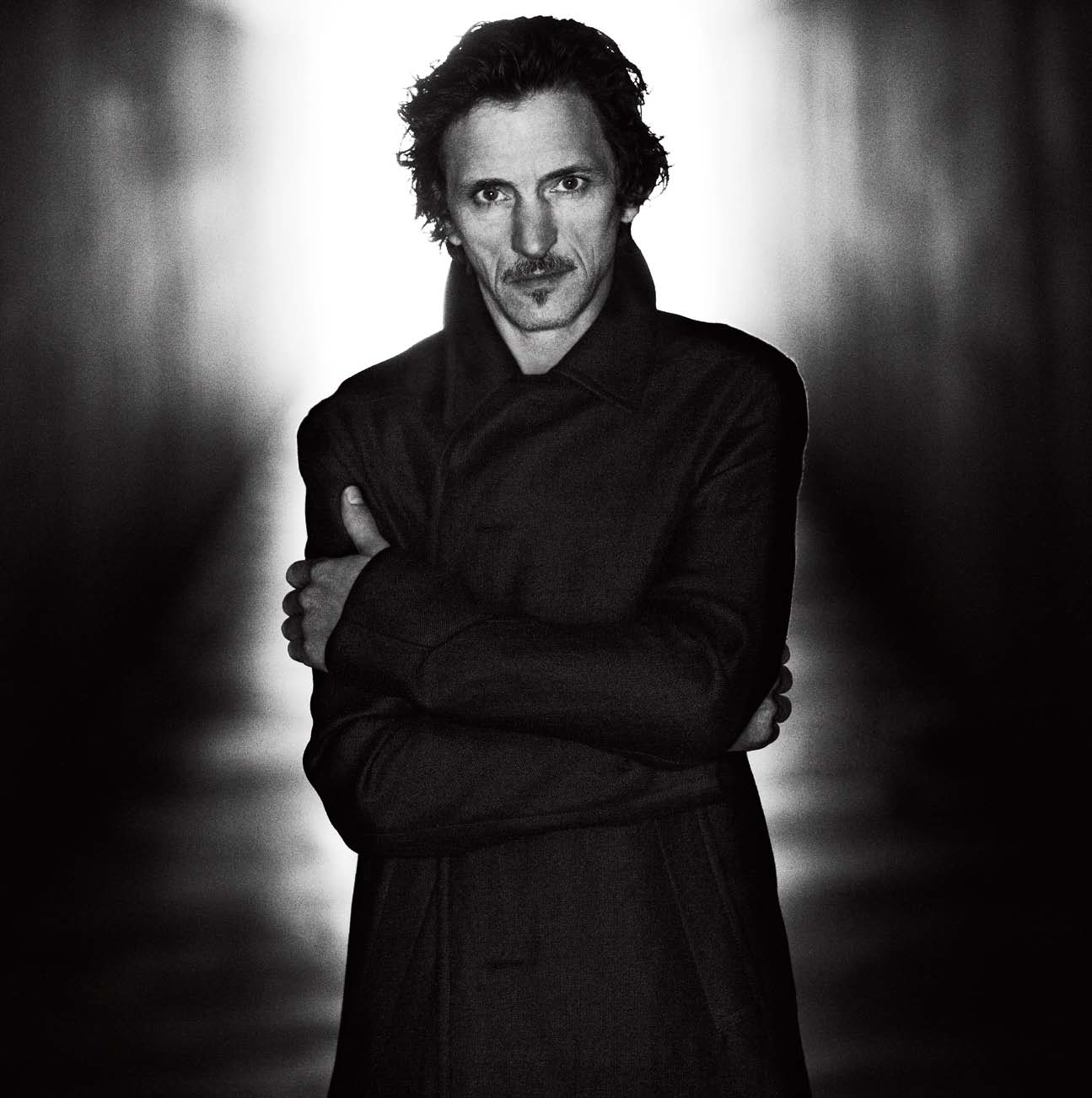

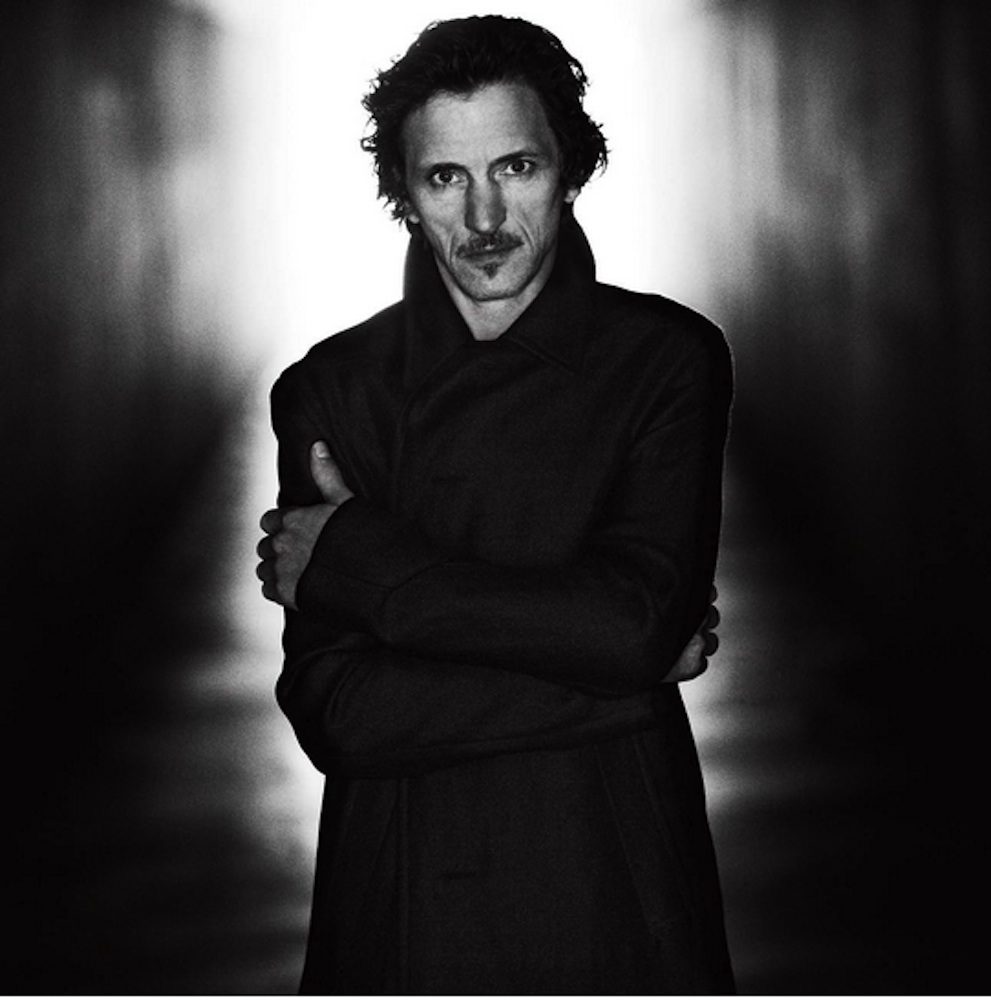

John Hawkes

“I remember the main mentor teacher sitting me down and very gravely telling me that I might possible have a shot at a career in dinner theater. I was just elated.” – John Hawkes

If John Hawkes has the kind of face that you feel like you’ve seen a thousand times, it’s because you probably have: His reÌsumeÌ of movie and TV work is long, full, and dates back nearly three decades. He has had small parts in a string of high-profile movies such as From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), Rush Hour (1998), I Still Know What You Did Last Summer (1998), The Perfect Storm (2000), Miami Vice (2006), and American Gangster (2007). He has appeared in a bevy of long-running shows such as Northern Exposure, Wings, ER, The X-Files, Touched by an Angel, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Nash Bridges, 24, and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. He has done a healthy spate of independent films such as Toni Kalem’s A Slipping-Down Life (1999), Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), and Vera Farmiga’s Higher Ground (2011). He has even cracked premium cable, with extended arcs on the HBO series Deadwood and Eastbound & Down.

For years, Hawkes worked steadily and ate regularly. But for whatever reason, he never quite managed to bite his way up the Hollywood food chain—that is, until his performance two years ago in the Debra Granik–directed indie Winter’s Bone (2010) as Teardrop Dolly, a tragically flawed meth addict who guides his niece, Ree (played by Jennifer Lawrence), through rural America’s brutal underworld in search of her father. Accolades and awards followed—including an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Hawkes followed up Winter’s Bone with a smaller role in Steven Soderbergh’s star-studded pandemic thriller Contagion, and a larger, critically acclaimed one as a perversely corrupt cult leader in Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene. Steven Spielberg also cast him in Lincoln, the director’s highly anticipated new biopic of Abraham Lincoln starring Daniel Day-Lewis as the 16th President of the United States, which is set for release later this fall.

Nevertheless, it’s Hawkes’s work in another new film, The Sessions, that might very well prove the real eye-opener. Directed by Ben Lewin and starring Hawkes in the lead role, The Sessions is based on the true story of Mark O’Brien, a poet and journalist whose body was left ravaged and contorted by a childhood bout with polio. Spending his days immersed in an iron lung, O’Brien longed to lose his virginity in the midst of middle age—an impossible dream until he met an irreverent sex surrogate (played in the film by Helen Hunt). Hawkes’s performance in The Sessions is a bravura turn marked by astonishing minimalism: Due to his character’s severe physical limitations, he can do little more than move his lips, but he still manages to convey worlds of emotion.

Dan Auerbach, singer-guitarist of the Black Keys, connected with Hawkes, 53, from a tour stop in Helsinki, Finland, to discuss The Sessions, the long road to recognition, and what happens when a vagabond outsider finally finds his way in.

DAN AUERBACH: Where are you?

JOHN HAWKES: At home in L.A. What about you?

AUERBACH: Just got off stage in Helsinki.

HAWKES: No shit? How was the show?

AUERBACH: It was great, actually. I woke up in Oslo, came to Helsinki, and I think we go to Copenhagen next. You’re working on a new movie now, right?

HAWKES: Kind of. It’s been a frustrating several months of almost being busy. I’ve lined up several independent films that have had real problems getting their money. There are indies with names much larger than mine attached that are having the same issues, so it’s been real stop-and-go.

AUERBACH: So how did you wind up doing The Sessions? You got the script, read it, liked it, and just did it? Is that how it worked?

HAWKES: Yeah, exactly. I’d had some luck around awards time with Winter’s Bone, so I got sent what was, for me, a pretty great little pile of scripts. The one I liked the most was The Sessions. It probably had the lowest budget, but to my mind, it was the most interesting role.

AUERBACH: Were you scared at all about taking a role where you could essentially only move your eyebrows?

HAWKES: The joke is that I was always on my mark. I never strayed off camera. [both laugh] But yeah, there was something challenging—and a little scary—about it. Before I met with Ben Lewin, he told me, “I’m the short, bald gimp with crutches and suspenders. That’s how you’ll know me.” Sure enough, he was as described. So we began to talk, and he had an amazing sense of humor. He’s Aussie and a polio survivor, and maybe because he hasn’t made a feature in almost 20 years, he very much seemed outside the Hollywood system—a person I could relate to.

AUERBACH: I didn’t know that he was a polio survivor.

HAWKES: He is. People got it in different strengths. Mark O’Brien ended up in an iron lung at about 6 years old. Ben got it when he was quite young. It was debilitating as far as not being able to really walk without crutches, but he’s mobile and able to live a normal life. He’s got a wife and three amazing kids and is one of the funniest people ever—right there with all of the oddballs.

AUERBACH: Was it weird playing a real person instead of a make-believe character?

HAWKES: I don’t know if it’s like covering a song by someone you admire, exactly, but it adds a certain weight of responsibility. You just try to do right by that person. You can never get it exactly perfect, but you try to get as close as you can to what the truth of that person was or is. Mark passed away 13 years ago, and I felt a responsibility to his memory and to the people who loved him. It’s a good responsibility. It adds an extra layer that makes you want to do your best.

AUERBACH: So what was the hardest part about playing the role?

HAWKES: It was physically taxing, but if something is in the script, then you have to honor that. So along with the friendly props people, I helped design a foam ball that I’d lay midway down the left side of my back to try to simulate the curve in Mark’s spine. It was uncomfortable, but a minute amount compared to what many people deal with. In the film, Mark says to his priest that he hasn’t seen his penis in 30 years. It was challenging, but there was also an ease about it, in a strange way.

AUERBACH: You said that The Sessions probably had the smallest budget of all the movies that you’d read scripts for, but I did recognize a lot of the other actors in the film.

HAWKES: Well, a lot of friends did favors. There are a couple of Deadwood people in the piece, and my friend Rusty Schwimmer came aboard. You’ve also got Bill Macy, Adam Arkin, and, obviously, Helen Hunt. As a musician, there are things that I’m sure you do that are more labors of love. This was one of those, for sure.

AUERBACH: Did you talk to the other actors before everyone committed?

HAWKES: No. I came right aboard as the first one in. I wasn’t sure I was exactly right, though. One of the very first things I asked was, “Have you considered disabled people for the role?” And Ben said, “Of course.” He’d reached out to various organiza- tions and did his due diligence trying to begin there. That would be ideal, obviously, if there was someone uniquely suited to play the part, but he never quite found who he wanted. He did put several really great disabled people in the film . . . But, yeah, that made me a little nervous—to kind of steal work from an underrepresented group.

AUERBACH: For what it’s worth, I think you did it justice. So, I wanted to ask you about something. I read somewhere that you hitchhiked across the U.S.?

HAWKES: I hitchhiked with a buddy from Austin, Texas, to Colorado trying to make it to Washington state, but I kept running out of money. Then I hitchhiked by myself from Colorado to Minnesota in the middle of winter. That was interesting. [laughs]

AUERBACH: Did you meet any—

HAWKES: Characters? I met a guy who said he’d just robbed a convenience store. That’s the fastest I’ve ever ridden in a car for a protracted amount of time, and he didn’t drop us where we wanted to be dropped . . . We weren’t really in a position to tell him to slow down. The guy was covered with tattoos before it was cool to be covered with tattoos—it definitely meant that he did time or was a white supremacist. Whatever his deal was, he showed us the weapon. He said he didn’t plan to go to Denver to rob a convenience store—he went there to get money that his sister owed him and she didn’t have it. So he picked us up to change the description: Rather than one man in a blue Mustang, it was now three men in a blue Mustang, which somehow he thought would be better. So we just shut up and let him drive. [both laugh] But I’ve hitchhiked as recently as two years ago. I was stuck in upstate New York working on a movie that Vera Farmiga was directing [Higher Ground]. It was pretty low-budget— they’d put us up in a bed-and-breakfast that was just bed. On my days off, there’d be no food, and I had no car, so it was either walk or hitchhike into town. I did a better job hitchhiking back with groceries in my hand because people put the story together quickly: “Oh, you’re someone who walked into town and bought groceries and live back down the road.”

AUERBACH: I would immediately think that you were carrying a shopping bag full of guns and ammunition. [Hawkes laughs] That guy who picked you up in Colorado sounds a little bit like Teardrop in Winter’s Bone.

HAWKES: There might be a little of that guy in Teardrop on some level. I remember a vibe that was coming off him strong.

AUERBACH: That silent intensity? That scariness?

HAWKES: For sure. That’s not my nature normally, so I needed to figure out how to get that for Teardrop. Often, observation is a good way to begin.

AUERBACH: Teardrop was kind of a game changer for you, though—like your hit single.

HAWKES: That was my Top 40 hit, man. [laughs] I’ll be a one-hit wonder. But Dan, it wasn’t adult contemporary or pop. It was number one on the indie charts. I mean, the lucky thing for an actor is that you generally get paid for what you do fairly quickly. For a musician, people are tough to chase down. They’re both difficult and kind of cutthroat businesses, but I just want to keep making good songs, whether they chart or not.

AUERBACH: Yeah, both of these businesses have long histories of completely screwing people and totally making them—and it’s usually one extreme or the other.

HAWKES: I always refer to acting as having chosen a life in the circus. When things get rough, I just have to remember that I love being with people who have chosen that path. Those are the folks for me.

AUERBACH: I feel the same way. When do you think you were first drawn into that world?

HAWKES: I think it was during a bus trip to the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis that I took for a drama class when I was a sophomore in high school. I was going to see Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, and I had the worst seat in the house, but I was still just blown away. I had never seen a real play—it felt like a different world. They took us on a tour backstage, showed us all the stuff, and the actors waved at us when they were leaving. I was interested in how those people had made me feel things that I wasn’t feeling before. I’d certainly been moved by films and television shows growing up, but after that, I wondered if I could somehow make people feel things, too. That experience changed my life. I took drama class only because my sister had taken it as a fluff course. I thought it would be a goof, but I ended up taking it kind of seriously. I didn’t know that I’d be an actor, or how to even become one. I’m from a little town in Minnesota, and there weren’t any references for professional actors or any kind of creative artists. But through that experience, I had an innate desire to somehow avoid the straight world. I went to one year of college, studied theater, and did some plays, but I felt like that wasn’t necessarily the place where I’d learn how to become an actor. I felt like I needed to learn about life in order to be able to portray it. I remember the main mentor teacher sitting me down and very gravely telling me that I might possibly have a shot at a career in dinner theater. I was just elated. [Auerbach laughs] My brother was moving to Austin, Texas, so I moved down there with him. I’d never even been to Texas, but I kind of retired there at the age of 19.

AUERBACH: Austin is an incredible city.

HAWKES: I owe a lot to that place. Austin during the ’80s was my college, just hanging out with people who were smarter than me and learning from them. It’s an abundantly creative place. I worked 20 hours a week, did plays, played in bands, made visual art, got roped into modern dance, all kinds of crazy shit.

AUERBACH: Do you think that growing up in a small town was an advantage for you?

HAWKES: I do. I got to study people closely and brush up to them in an intimate way. Weirdly, the big events—birth, death, marriage—feel magnified. I learned to wrestle because my buddy’s dad from down the road was a wrestling coach. That was my main passion for 10 years. But I also hung out alone a lot. I’d wander around the woods, field manual in hand, kicking over logs and identifying larvae. I was an odd kid, a real nerd. But just to be alone, to use your imagination, and to not have a lot of stimuli and culture, was kind of a great thing.

AUERBACH: I always felt coming from Akron [Ohio] was a total advantage. Coming from a smaller place always made things feel more personal, which is really what it’s all about.

HAWKES: Akron had a pretty rich creative scene. Your musical forbears from there are pretty amazing.

AUERBACH: Yeah, but that was in the ’70s, and then it went away. Devo and The Cramps didn’t get big until they went to New York City. Chrissie Hynde didn’t get big until she moved to London. When I was growing up, there wasn’t even a place to play— just one little bar. If we wanted to have a gig, then we had to drive 45 minutes up to Cleveland. When did you move to L.A.? When did things start for you?

HAWKES: I became known in Austin as a decent theater actor, so I got a local agent, and through that I’d get cast a lot in these one-liner Hollywood movie parts—you know, “They went thataway!” or “Anybody want a Coke?” I remember Dennis Quaid being real nice to me. But the question always was, “If you’re an actor, then why are you in Austin?” And I’d say, “I would never live in New York or L.A. Why would I leave here?” And they’d respond, “Well, you could maybe play better roles.” Eventually, I just decided to roll the dice. When I moved to L.A. [circa 1990], it was still difficult—I did some telemarketing at one point. But I was determined to stay and just kept trying to do a good job every time out. I’d pretty much whore myself out to anything that would pay in those days. I wasn’t good at doing commercials—I’m kind of glad for that. But if you’re a sculptor, you sculpt. If you’re a dancer, you dance. And if you’re an actor, you act. I heard someone say that all it takes is the first 50 good breaks and you’re on your way. Well, I’m in the mid-40s somewhere, so that’s good. [both laugh]

AUERBACH: So your character in The Sessions knows that three women who loved him will be at his funeral. How many are you going to have at yours?

HAWKES: [laughs] That’s an interesting question, Dan. I hope a few. The more the merrier.

PHOTO: DAN AUERBACH IS A SINGER AND GUITARIST IN THE GRAMMY-WINNING DUO THE BLACK KEYS. GROOMING PRODUCTS: CHANEL, INCLUDING HYDRA BEAUTY. STYLING: DAVID THOMAS/OPUS BEAUTY. GROOMING: FRANKIE PAYNE FOR CHANEL/OPUS BEAUTY. SPECIAL THANKS: PIER 59 STUDIOS WEST.