Joachim Trier’s Family Dynamics

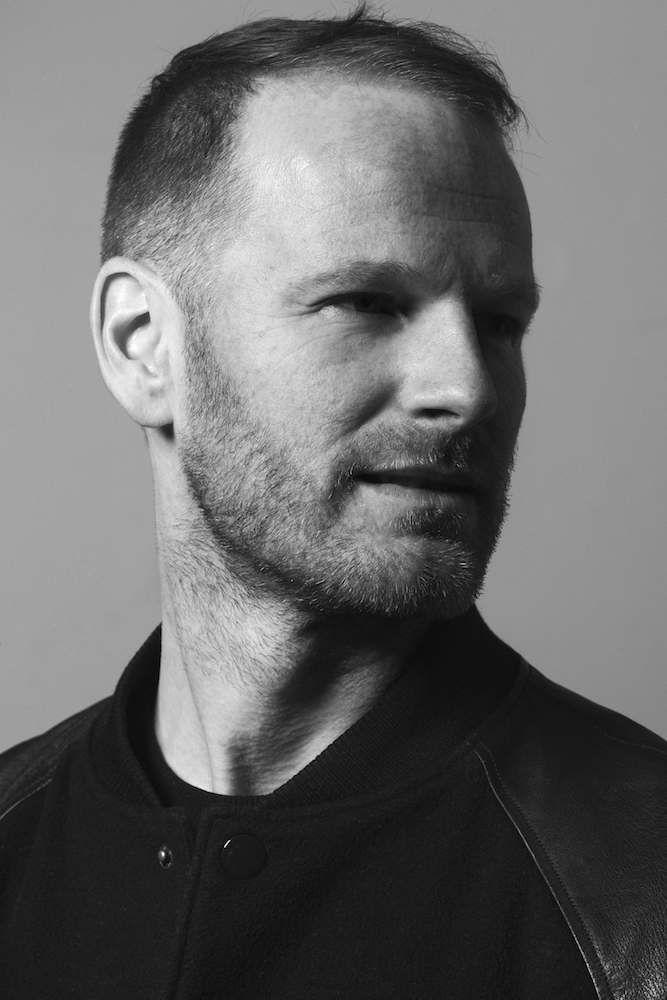

ABOVE: JOACHIM TRIER. PHOTO: COURTESY OF RASMUS WENG KARLSEN/THE ORCHARD.

In Joachim Trier’s first two films, the moving coming-of-age portrait Reprise (2006) and the elegiac Oslo, August 31st (2012), the Norwegian writer-director painstakingly renders full-bodied, nuanced accounts of the malaise of young men. The two films are companion pieces of sorts, Reprise chronicling the exploits of two best friends with literary ambitions; Oslo gut-wrenchingly narrowing in on 24 hours in the life of a 30-something hipster grappling with heroin addiction. But with his third feature (and first in English), Louder Than Bombs, out this week, Trier attempts something more ambitious, widening out to probe the dramatic potential of a family in mourning.

Years after Isabelle (Isabelle Huppert), a well-esteemed war photographer, commits suicide by crashing her car, her widow (Gabriel Byrne) and adult and teenage sons (Jesse Eisenberg and Devin Druid, respectively) are reunited in the family house in Nyack, New York, in advance of an upcoming retrospective of her work. The slippery layers of memory and the relativism of truth become the fulcrum of the film as the three generations of men grapple with grief and their recollections of their wife and mother. According to Trier, classic American ensemble films like Robert Redford’s Ordinary People (1980) and nonlinear works such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975) and Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) were major influences on forming the film’s fragmented, patchwork flashback structure. Interview spoke to Trier last week in New York about modern masculinity, suburbia, and Hollywood.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Something that I found so compelling about your first two films were that they were very intimate portraits, of a friendship, or of an individual. What was the decision behind widening out to an ensemble family dynamic?

JOACHIM TRIER: It had to do with exactly what you’re asking, actually. We felt that we had explored a very intimate type of storytelling, almost tactile, just in getting close to the skin, the sense to being close to someone who was alien from the space and the world that he was actually living in. So, what would happen if we put characters up against each other and see how the drama comes out of their perception?

As an example, [with] Gabriel Byrne and Conrad, the son played by Devin Druid, we loop back and see the individual perspectives on the same situation sometimes. Stuff like that was kind of the driving force. We were curious about that. I mean, I don’t know anyone that doesn’t have an ongoing process of relating to their family, whether it’s in the absence of someone, or too much presence of a parent, or a child that’s trying to become autonomous. This is a central drama that we all have to deal with. Since I was working in English again, I thought that’s more of a shared, human thing I could talk about, even in a culture that’s not 100 percent my own.

KELSEY: The central event that happens is Isabelle’s character’s death; we understand the truth of it, but everyone represents it differently.

TRIER: When you lose someone close to you, you’re forced to carry the memories that you shared with them alone, and that’s sort of the burden that they are dealing with. The two brothers don’t have a shared narrative of who they are as a family, and that is very tricky. The father is more mature, but I feel like there is an ongoing debate between Jesse and Gabriel’s characters about who has the right to define what happened to their mother.

KELSEY: Let’s talk about the film as a study of masculinity across generations. Was that something you were interested in?

TRIER: It occurred to me later. It’s embarrassing, I wish I could be one of those people with a clear plan and then I do it and bring it to life. I worked with Eskil Vogt, my co-writer, and the team, the actors and everyone, really much more spontaneous. We would go through these phases of intention and spontaneity and intention and spontaneity and just doing what you think is interesting at the time. It turned out that we ended up after a while in the script stage going, “Wow, I guess we are telling a story of men trying to deal with new women in their lives in three generations,” a 15-year-old having just gone through puberty, his first erotic fascination for someone in his class; a young father who is unable to connect to his child perhaps because he’s got an unresolved relationship with his own parents; and a grown man who has to play the role of both the father and mother.

Masculinity was your question and it’s such an interesting thing. I think of them as humans and afterwards comes, “Oh, it also deals with gender.” I work more instinctively when it comes to my characters but what I figured out with this story is we’re talking about a more modern father portrait, than the classical patriarch. It’s the opposite. He’s more present. He’s almost smothering them with this attention and they don’t want it. So, I’m trying to do something new here with that type of male character, I guess.

I used to love Death of Salesman. Willy Loman tried to be the patriarch in a very democratic America. He’s trying to create this family that has importance, but he’s been away from them so much and you see the two sons struggling with their male identity because the father failed. But here, we try to talk about the mother who’s out of the house and is an admired mother. I thought that was an interesting take on a family as well. I must add that I hear myself saying that, it sounds like you can only admire people for their work, which is obviously not the case. But that distant type of idealization, that I think particularly Jesse Eisenberg’s character is doing with the mother, makes it hard for him to grieve.

KELSEY: Coming from Scandinavia, how was it filming in the American suburbs?

TRIER: [laughs] I actually liked it. It was weird. I’ve constantly been asked about this, “Oh, did you feel present and at home in an environment you didn’t grow up in?” We filmed in a house upstate New York with my Swedish DP and a wonderful American production designer, Molly Hughes. She looks over at us as we’re looking at some pine trees through the window and she says, “This is like Scandinavia, isn’t it?” We’re laughing and we’re like, “Yeah!” in terms of the feeling of space, light, and nature, and this urbana up against nature and those borders of the city. They remind me more of home weirdly enough.

KELSEY: Once we get a little bit further into Conrad’s life and his day-to-day, the film takes on a taste of the very prototypical high school tableau, the way that high school is reflected on film, and whether it’s an ’80s movie or…

TRIER: The relationship between the mythology of high school and the reality of high school, it’s a very relevant question. I’m inspired a lot by John Hughes and Paul Brickman’s wonderful Risky Business, that sense of being at that incredibly open moment in life that high school can be, yet within those restrictions of the hierarchy. But then to do justice to the American audience—and also to film—we went to high schools, and I hung out a bit and talked to a lot of kids. It turned out that a lot of that stuff is still relevant, but what is very different from the ’80s—from when I grew up—was that the gamer kid, the nerd introverts, found another output where they’re connected with each other away from the social arena of the playground. There’s a different playground which is a virtual one, which has become tremendous. It’s kind of a weird subculture that’s emerging that I’m fascinated by, so we’re adding that to the mix. It’s not just admiring the cheerleaders, which is, by the way, treated as mythology. And it does exist. I mean, you’re aware, I’m sure, as an American. As Jesse says, “They still do this shit?” [laughs] I kind of find it beautiful. It’s really fascinating. As a European I thought, “Wow, that’s beautiful. They fly in the air. It’s beautiful.”

KELSEY: What is your writing dynamic like with Eskil?

TRIER: That’s a big question, huh? I think we start out always sitting in a room and talking for a long time, and then it’s almost sort of therapeutic. We talk about life and movies. We both are real movie buffs. I think we probably spend half of the first year on ideas and just talking about movies we see everyday. Really, we are procrastinating. Slowly, by the end of a period of a few months, we will have figured out what kind of what stuff is inspiring us. By that time we have also talked about stuff in our lives.

There’s tons of stuff, but it never starts with a story—it’s based around a situation or a character or just a formal thing that could be done with a movie. With Louder, it was quite special; we had so much material. We start structuring it into a story and we have to throw 90 percent of our stupid ideas on the floor and it changes to become very structured and disciplined. But, it should always be dealing with themes.

We’re inspired not necessarily by the stories of literature, but the spirit of the novel’s ability to do very freeform things. After we had written the script, and I was going into pre-production, someone suggested that I read Freedom by Jonathan Franzen, who’s a great writer, so I wanted to read it anyway. I did, and it just occurred to me that how easy it is in a book to do, when the writer’s good like Franzen, to let him be free. That’s kind of how we work too. We want to have a freeform in what we do.

KELSEY: Do you think it’s more difficult to achieve that through cinema?

TRIER: Yes, because of the tempo. Writing a book like Franzen, I would never be able to do that. I admire him tremendously, but what I think is difficult at the moment is that people have become very expecting of a certain type of dramaturgy, so movies are getting geared toward a specific type of dramaturgy at the moment. I think we need to challenge it. People immediately think that they will be bored. No, no, no. We don’t want to make general cinema. We want to really give people something to think about, have fun with, laugh at, cry at, but in a slightly different shape and form.

This is kind of an expensive film for an indie, and it’s important right now that us filmmakers wear our own jacket and not try to be, “Oh, the adults want us to do the proper thing.” Fuck that. I think ultimately, that’s what people are going to respond to, that you bring a personal attitude and temperament to the movies we make rather than to try to buy into some sort of notion of success that’s pre-imposed on us. Right now, it matters. Movies are at an exciting place, but also at a tough place right now, so this is important that we do our thing. That’s what we want for the audience.

KELSEY: Your earlier films have been quite successful, critically. Given that success, have you found that people have tried to corral you to do a movie that maybe you don’t want to do?

TRIER: Generously, people have offered me all kinds of things. Particularly after Reprise, I read tons of scripts from Hollywood. It’s interesting. I guess I’m also really geared to my own material for the moment. We’ll see. It could be a fun dialectic at some point maybe in my career where I try to… I want to keep experimenting with types of movies, but I wouldn’t want to work without doing something that really matters a lot to me personally. As long as I’m allowed to write and they pay for me to make a movie every once in a while I’m not complaining. I’m super happy. There are so, so few people who are allowed to do this. I’m really quite grateful to be one.

LOUDER THAN BOMBS IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE THIS FRIDAY.