Jehane Noujaim and Karim Amer Take the Square

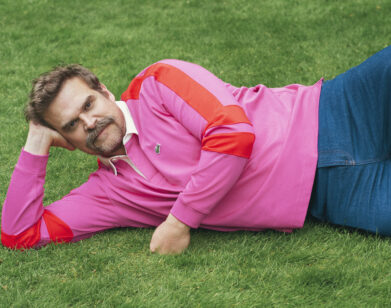

ABOVE: EGYPTIAN ACTIVIST AHMED HASSAN IN JEHANE NOUJAIM’S DOCUMENTARY THE SQUARE. COURTESY NOUJAIM FILMS.

When Jehane Noujaim’s The Square screened earlier this year as a work-in-progress at the Sundance Film Festival, it captured enough attention to win the festival’s Audience Award, and the same happened when the documentary was shown months later in Toronto. Filmed on the ground from first rumblings of protest in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in early 2011 through the removal of Hosni Mubarak and Egypt’s tumultuous transitional period of military rule, and the ousting of president Mohamed Morsi this summer, The Square is an intimate, viscerally immersive account of a revolution in progress and the young activists who are fighting for a new Egypt.

Noujaim, an Egyptian-American filmmaker and director of Control Room and Startup.com, connected with her producer, Karim Amer, and a group of activists from disparate backgrounds, beliefs, and affiliations in Tahrir Square. Together, they have co-opted the authorship of the revolution’s narrative to be one written by the Egyptian people, independent of versions told by the Egyptian and international media.

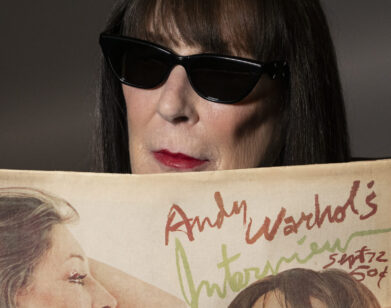

Interview recently sat down with Noujaim and Amer shortly after The Square screened at the New York Film Festival.

COLLEEN KELSEY: In regards to the events at Tahrir Square, were you engaged initially as a citizen or as a filmmaker? What first brought you there to document it?

JEHANE NOUJAIM: I make films because I’m curious about a story, not because I know the answers to it. This was an example of something I was very curious about, and I knew I wanted to make a film about Egypt if it exploded. However, if I was not a filmmaker, I would have been there as a protestor, so it’s really both. I had made a film in 2007 about three women that were fighting for change in Egypt by filming all of the corruption that was happening at the various election points and then sending that footage and testimony in. And at the time we were filming, things were heightening in terms of the anger towards the government, but it never quite reached the level that it did in 2011.

KELSEY: How did you and Karim first connect? I know you met in the square.

NOUJAIM: He was doing a couple interesting things. I was there with my camera. Karim was setting up, with his cousin, the third stage in the square. There were two stages already set up, one by the [Muslim] Brotherhood and one by the sort of, lefties, and Karim wanted to set up a stage with his cousin that was for anybody that wanted to speak regardless of political background. I thought, “This is a fascinating character to follow,” somebody who the West can relate to because he grew up in Miami, and somebody who is very connected. So I followed him for about a week or two, when he said, “I don’t know if I should be a character in this movie, but you definitely need a producer to figure stuff out.” So he then became the producer of the film and this is how the entire team came together, which was quite an awesome process. I’ve never been a part of that before, where you literally meet in a square, the RDP comes and tells us how to use the camera and we ask him to be our DP. Ahmed, who became our character in the film and then learned how to use the camera, ended up shooting a quarter of the film because he was the person brave enough to be on the front line. He films some of the most intense battle footage.

KELSEY: Had you produced a film before?

KARIM AMER: I’ve produced other films but not like this. I’ve been interested in it, but just to take it on full throttle like this as a complete independent… We weren’t able to raise really much from people, because the funding source needed to be independent for us to get the access we did. We couldn’t get backed by any of the major television networks because none of them would have lasted this long. For most people the story was already over when ours was just starting. For all of us on the team, it wasn’t really just a film, it was a lot more than that. We felt an obligation to history, we felt an obligation to our country, and we felt an obligation to the people in that square to make sure their story would get out there. No matter what, what we were unwilling to give up is the idea that the narrative could be written by whatever the Egyptian media was going to say, or the narrative could be written by the international media.

NOUJAIM: And that’s very important for a country that has been colonized by every major power that exists.

AMER: Since Cleopatra, basically.

NOUJAIM: I think that claiming the narrative and having Egyptians tell the story of the Egyptian Revolution is incredibly important for the legacy of this historical moment.

KELSEY: How did you select Ahmed as the main character? Collectivity is incredibly important in the revolution, but everyone has a singular opinion or POV. Why his perspective in particular?

NOUJAIM: Well, it was love at first sight, and I think for everybody on the team. I met him probably two days after I landed in Egypt. A friend of mine was doing a news story on him, and I met him in the square. You have to fall in love with your characters to want to spend three or four years with them. You never know with these films, but you have to be following people that you feel are inspiring you, surprising you, making you laugh, people that you want to be their friends because if you don’t want to be their friend, then you won’t be able to have an audience want to be their friend. With Ahmed, he was somebody who you could see that he was really the heart and soul of this revolution. He was able to have discussions with people where he would bring up an issue with people who had massively different opinions from him, and he would be talking to three people and in 10 minutes there would be 30 people, 40 people surrounding him and he was able to sort of moderate this intense conversation between people. People were talking about politics for the very first time. So to be able to capture that, and have him be our leader through which we could capture that, was very important. He’s also incredibly poetic.

KELSEY: One of things I really liked about the film were the sequences of people having discourse and just sharing their opinions.

AMER: I think what happened to Egyptians was this sense of opportunity. There was a dedicated few unwilling to compromise on that dream, they were unwilling to relinquish that right. And that’s what tied all those people together, whether it’s our main characters, who come from completely different walks of life, yet all stick to their principles, or if it’s people who are the other familiar faces you see in the film who are also part of that. So it is kind of like a band of brothers, a communal thing, which often times could only agree on what it didn’t want, and so there was always a unity in “We do not want this, and we do not want that.”

KELSEY: I know you drastically edited the film based on what was shown at Sundance, to consider recent events. How did you narrow down the scope of what was going to be included? The situation of the revolution is constantly changing.

NOUJAIM: Well, I think that there are two storylines you’re following. You’re following the story of the revolution and the square, and then you’re following the storyline of the characters and their interaction with that. The connection points when you are editing are: what are the most crucial moments for our public audience outside Egypt to understand this process of change and the revolution, and what are the most crucial moments as a human emotional story to really understand the arc these characters have been on? You marry the two, and that’s really how we ended up with the film. We had to really move from being attached to events, to focusing much more on the characters’ emotional arc.

AMER: That was a major shift we had to make in attitude because when you’re in the midst of an event, you really want people to understand everything that happens. People need to understand what happened on this day. Yet, there’s no truth validity really in the ability to describe everything that happened in an event because these events are so complicated. So what we felt is the only thing we could really provide is sense of what it was like to be there, to really take you there as an audience and let you experience it on a firsthand account, connect to someone on an emotional level, go on a journey with them, and come to your own conclusions.

KELSEY: Jehane, I know you were arrested and the police confiscated your cameras. I’m sure that hindered production on some level, but how did it affect your process on the film?

NOUJAIM: I think your tenacity increases when you see a massive injustice happening. The first time I really felt that was less when I was arrested than when I first saw Ramy, who was the singer of the revolution, being arrested and tortured. Here was this guy that was heralded as a hero of the revolution, turning the chants of the revolution into the songs of the revolution, and on every television screen internationally. Three weeks later he is pulled out of the square and badly beaten and tortured to the point where he couldn’t move for two months and nobody talked about it. There was a whole media blackout on it because it was the military and people at that point were afraid about talking about the military. I posted pictures of him on my Facebook and I had good friends of mine who are intelligent, knowledgeable people saying, “There’s no way that this is true, the military would never do this to one of their own, absolutely no way!” At that point you become like, “There’s another narrative going on here that is not being talked about. This is what needs to be shared to the world.” When I was arrested—

AMER: [interrupting] Which time?

NOUJAIM: Which time? [laughs]

AMER: It’s not easy making a film when the director keeps getting arrested and doesn’t learn from her mistakes and keeps going to the front lines.

NOUJAIM: So the first time was a massive moment of confusion. The second time, we were all together. There was a ceasefire between the protestors and the police, and so we went to the front lines to film the ceasefire, and then, maybe 10 minutes after we were there, we filmed this beautiful prayer that happened of protesters. Then a tear gas canister flies and all hell breaks loose and Dino, one of our producers, and Karim, runs toward the protestors’ side and I run towards the enemy side partly because there was tear gas going the other way, and partly because I really wanted to get the military perspective. How does it feel to be shooting on your on people? Everybody is drafted, so everybody in the military is like cousins with the people that are on the other side of the line. I really wanted to understand, is there a brainwash happening here? What are you thinking? So, I found a media guy and it was actually quite a funny scene that I filmed. They still have the footage. One day I will get it back.

AMER: I think that is part of what drives her as a director.

NOUJAIM: Boy, let me tell you, he was wearing this massive gas mask, he looked like an astronaut or a space monster or something, and all of them were decked out in American gear, yelling through this massive gas mask and he’s like, “These kids are attacking us, they are attacking us with everything they have!” We had just come from the other side where it’s like 17-year-old, 19-year-old kids in plainclothes with rocks as they’re being shot at and tear-gassed. So, I filmed this 15-minute interview with him and then I was arrested. I put myself in a situation where it was not a safe situation. If you go to Egypt you’re not just gonna get arrested, I got arrested because I was in a place where we shouldn’t have been.

AMER: And then the charges that she got accused of—

NOUJAIM: The charges are another story—

AMER: Burning cars, throwing Molotov cocktails, destroying public property…

NOUJAIM: That was the scary part, and it was scary being driven around in these huge big blue police trucks, and they disappeared us for eight hours.

KELSEY: How long were you detained for?

NOUJAIM: It was like 36 hours.

AMER: There was no space for women in two of the prisons we went to.

NOUJAIM: So in the end, I just sat in the police station.

KELSEY: Is there anything you are going to continue working on, or any other stories you want to tell outside of this film? I can image you have an enormous amount of footage.

AMER: We have a few stories to tell. This is kind of a big moment in history. There are things that we’ve filmed that we don’t even understand yet. We have a plethora of footage, over 1,600 hours. It’s quite an incredible archive. We feel that there is going to be more stuff to come.

THE SQUARE OPENS AT THIS FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25 AT FILM FORUM, AND WILL OPEN IN LOS ANGELES NOVEMBER 1.