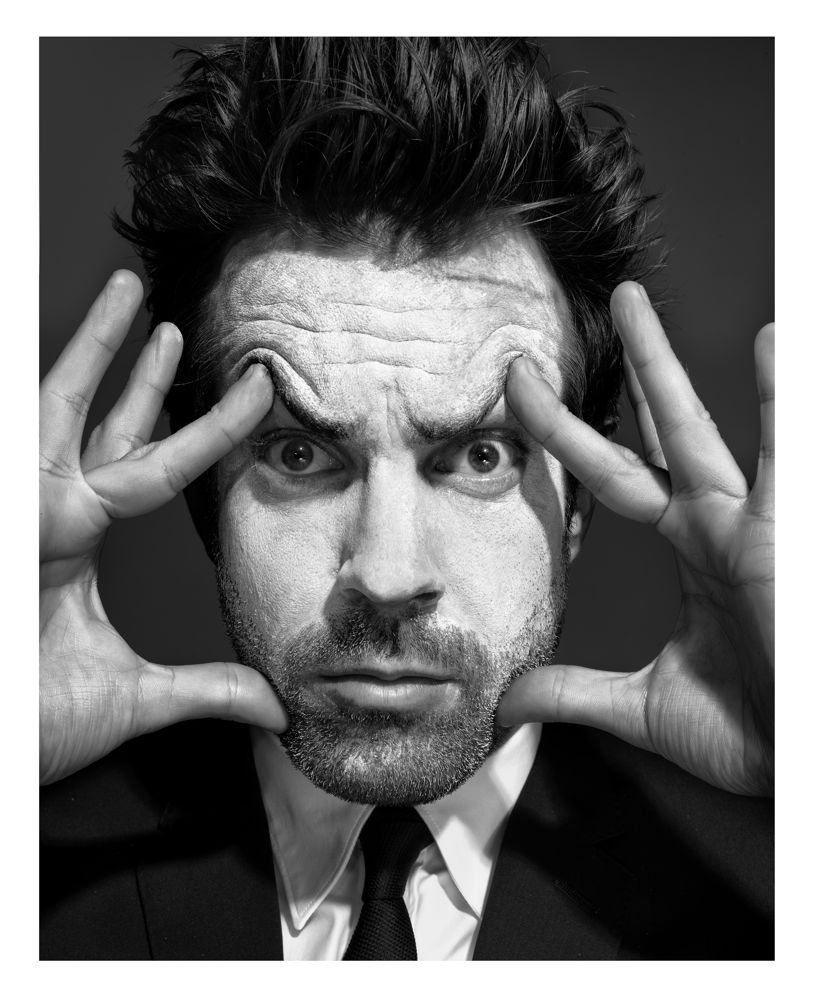

Jason Sudeikis

I was a straight man long before I knew what it was called. I was just the boring one. Jason Sudeikis

Based upon his eight seasons of deft-handed work on Saturday Night Live and in films like Hall Pass (2011), Horrible Bosses (2011), and The Campaign (2012), it was probably somewhat inevitable that Jason Sudeikis would eventually play a pot dealer or star in a big summer comedy. Thankfully, he gets to do both in Rawson Marshall Thurber’s new film We’re the Millers. In the movie, which hits theaters this month, Sudeikis stars as David Burke, a small-time weed merchant who assembles a fake family comprised of a stripper (Jennifer Aniston), a homeless teen (Emma Roberts), and a hapless neighborhood kid (Will Poulter) to help him smuggle a “smidge” of marijuana into the U.S. from Mexico at the behest of an eccentric kingpin (Ed Helms). (The determination of precisely what exactly constitutes a “smidge” is destined to become a hot topic during the doggier days of August.)

For his part, Sudeikis says that his approach to comedy is to not play it like its comedy—to tap into the internal logic of the character and the material, from whence, he says, the funny springs. We’re the Millers represents his first starring role in a major movie and an opportunity for the Second City alum to flex his SNL-toned muscles in a more substantial, wide-screen way. But it’s Sudeikis’s ability to infuse characters that abide by their own, at times, warped internal logic with a kind of endearing charm that remains one of his greatest assets (see Biden, J.; A-Holes, Two).

We’re the Millers is funny—like, genuinely funny—and a lot of the responsibility for that rests on the appeal of Sudeikis’s manifest dudeness, which is considerable.

Actor Michael Keaton recently spoke with the 37-year-old Sudeikis in New York.

MICHAEL KEATON: So George Wendt is your uncle?

JASON SUDEIKIS: Yeah!

KEATON: Are you tight with him?

SUDEIKIS: Very. Speaking of which, I actually have a Gung Ho [1986] movie poster. It’s framed. [Keaton laughs] And then George’s wife, my Aunt Bernadette, is an actress, too, and she was in Mr. Mom [1983]. She was in the grocery store—you hand your child to her.

KEATON: Yeah. They’re both such nice people. I could regale you with some Gung Ho stories about George, most of which usually started in the makeup chair. George would get to the makeup chair first thing in the morning, and he would review what our dinner was the night before and then ask what was for lunch and then start making plans about what we were going to eat that night. We were shooting in Argentina, so it was like, “Okay, boys. Looks like steak again tonight … “

SUDEIKIS: He wants to know what he gets after a day’s worth of work. He wants to know the reward on the other side of this crazy job he has to do for 8-to-12 hours.

KEATON: Obviously, George is not a small fellow, but he’s shockingly athletic and agile. We would play basketball a lot while we were down there.

SUDEIKIS: Real quick hands. But he was a huge deal—what a major influence it was on me, coming from Kansas to go visit Uncle George, who was joking around on the Cheers set and doing all these great movies, like Gung Ho and Fletch [1985]. I also loved that he knocked down the building of the house next to him and built a basketball hoop and a pool. I was like, “Well, that’s the job I’ve got to get.” I mean, he had a full-on three-point line and a glass backboard. It was everything the 10-to-15-year-old me dreamed of … The 37-year-old me still dreams of it.

KEATON: That’s what you call living large.

SUDEIKIS: He also had, like, this awesome BMW that he would drive like a maniac up and down Laurel Canyon. I remember sliding around in the backseat while my dad was sitting up front with George just jamming Bruce Springsteen, and George making my dad really nervous as he took these corners that he knew like the back of his hand.

KEATON: So you grew up in Kansas, right?

SUDEIKIS: Right.

KEATON: There’s something about guys from the Midwest who are funny.

SUDEIKIS: Yeah, Bill Murray and all those Second City people. But yeah, I’m about as Midwestern as they come.

KEATON: I read that you did Second City in Chicago, but also were a founding member of the Second City Las Vegas. I did Second City workshops out here for a while, and we thought it was odd when it was in a strip mall in Pasadena. But I can’t imagine the Second City in Las Vegas.

SUDEIKIS: It was at the Flamingo. I mean, we could hear the slot machines going. The first month you’re there, you hear every little extraneous noise because you’re like, “I’m in Las Vegas.” The people at the Flamingo were like, “We can’t turn down those slot machines. That’s why people are here.” And just a piece of glass separated us from all this noise. So we tried to make jokes about that, about the crazy lines, about the quality of the food in the buffet, basically trying to do what Second City is known for, which is social and political satire. But they were like, “You know, I saved my money for the last year, and this is my vacation, and now you’re making fun of it.” So we learned to embrace the craziness of it. I think the show got a lot better after we all had lived there for a couple of months and sort of got used to these tropes and archetypes of people that you’d see there. It was a good lesson to have learned—and oddly, a very helpful one to have learned when I eventually got to SNL.

KEATON: It’s what you have to do. I did stand-up for a while and you have no idea how wrong you can be.

SUDEIKIS: Well, you glance at the audience, and you don’t know who there has just lost $10,000 at a craps table, and they’re like, “We’re sorry about that. Here’s a free steak and go watch a skit-comedy show.” So they’re sitting in the front row with their arms crossed next to some young blond lady who I can only assume is their daughter, and they just don’t want to laugh at shit. They’d be like, “Who the hell are you? We wanted tickets to Gladys Knight, but she was sold out, and now we’re going to sit here and watch you jerk-offs.” It really is the craziest town. I thought I was going to be there six months and ended up staying almost three years. It was so interesting because it was a rotating cast, so we had people coming in and out all the time and I got used to doing it with tons of different people. It forces you to learn how to manufacture quick chemistry with people. They eventually all became friends, but it was the most transient town. Everybody had a get-rich scheme. I once had a conversation with a guy, who I eventually saw getting a blowjob in a hot tub from my balcony, but he had a new invention.

KEATON: You weren’t having a conversation with him then?

SUDEIKIS: No, I was not. My mouth was full. [Keaton laughs] This was when I first met him. He thought he came up with a brilliant idea for a new handle for a slot machine. He was like, “What if the handle pulled down like a cord, instead of pulling forward?” He had this whole theory about how it was better for the rotator cuffs for older people— [Phone disconnects. Sudeikis and Keaton are both called back and conferenced together again.]

KEATON: Sorry, we got disconnected. That was, like, the worst place to get disconnected, too-right in the middle of a blowjob joke.

SUDEIKIS: When you don’t get to hear the laugh on the other side, you’re just like, “Oh, I offended him.”

KEATON: So this guy thought he invented what?

SUDEIKIS: His scheme was to come up with a new handle for a slot machine, so that it was more like a cord than an arm. He was gone within two weeks.

KEATON: People get caught there.

SUDEIKIS: I did. I mean, I think I went crazy there a little bit, really trying superhard to get into Blue Man Group. I developed a mild case of alopecia where I started getting bald spots on my beard. It was crazy.

KEATON: Were you funny when you were a kid? Was your family funny? Were your friends funny?

SUDEIKIS: Well, my dad is very funny and he introduced me to a lot of stuff. The people he liked, I ended up really liking—except for basketball, because I love Magic and he loved [Larry] Bird. But with everything else, we were right down the line. I also had funny friends. I’ve got videos from, like, sixth grade, and it’s my buddies Ryan Landry, Terry Maher, Matt Bail—I’ve just been stealing from them for years now. I was a straight man long before I knew what it was called. I was just the boring one. But they were so clever—and those are my friends who didn’t even choose to go into a life that we call “the arts.” And then I have all the friends that I made in Chicago or in Las Vegas who are funny for a living and could also still blow me away.

KEATON: How did your family feel about you getting into this?

SUDEIKIS: My dad took me to see Beverly Hills Cop in the theater in 1984. If I didn’t want to be you or Chevy Chase or Harry Anderson, I wanted to be Eddie Murphy because my dad had taken me to go see that stuff. So he was totally supportive. Luckily, I also happened to have an uncle on Cheers doing quite well, so that definitely helped. My mom certainly supported me as well.

KEATON: I was watching Horrible Bosses, and one thing I noticed is the way that you play those “in-between” moments in a scene and this total commitment that you have to the truth of the character, sometimes even at the expense of maybe getting a laugh for yourself.

SUDEIKIS: I’m always a fan of those smaller moments. In my head, I sort of go about performing a comedy show like it’s not a comedy show. I made the choice to move to Chicago to try Second City because of guys like Scott Adsit, who was on 30 Rock, and Kevin Dorff, who did Conan for years. Those are my heroes, and they were great actors, but they didn’t push, in the sense of, “Oh, I get either three little laughs here or I just sort of save it all and I get one big laugh …” Those guys played it real and that’s what I liked.

KEATON: I think the general theme of Second City is basically that, too. In the workshops, I was always pretty unhinged. I would just go for anything I could that would make me laugh and make other people laugh until I started to realize that that was really going against the basic ethic of it.

SUDEIKIS: Oh, I came in that way, too—all loud and busy. But I slowly picked up on what I responded to. I think for a lot of people, when they hear the word improvise these days, they have a tendency to think that the camera just rolls, because now we have a little more leeway with everything being digital, so you’re not spending as much money as you were when you were shooting film. But a lot of improvisation ends up being about just thinking outside of the box in the scene. It’s not improvisation as much as it is quickness or making it real. I went to see Batman in 1989 at Glenwood Theaters in Kansas, and I always think about that moment when you’re going to see Vicki Vale [played by Kim Basinger], where you mouth silently, “I’m Batman, I’m Batman.” [laughs] I’ve probably stolen versions of that so many times in so many different ways. But it’s those tiny moments where you get to capture someone letting their guard down that I like—especially in that genre.

KEATON: You know, I just worked with Alejandro González Iñárritu, who is kind of mind-blowingly good, and he said that we were to always be asking the question “What’s the truth in the scene? What’s the absolute truth here?” Obviously, there are always things that you’ll do in a film or in a show that are just there to be funny, and they’re just vague and silly and crazy, and you can cut loose and do whatever you want. But then there is something that I used to do a lot when I improvised, which was more about having freedom in the moment, where you say, “This is the truth coming out of this guy’s mouth. As outrageous as it seems, what he’s saying is within the character.” I worked this past year with [Bill] Hader, and I was telling him how incredible I think these last two casts on SNL have been. First of all, Hader is a monster.

SUDEIKIS: Oh, yeah. People have no idea—he’s given them already a hundred faces, but he’s got 900 more. You take him out of the live show element and give him takes … He’s remarkable. Him, Fred [Armisen], Kristen [Wiig], Andy [Samberg], Will Forte—people haven’t really even seen what they can do because the work is so specific in terms of what’s asked of you on SNL.

KEATON: I love this guy Taran [Killam]. I don’t know how you kept a straight face during the Bieber sketch with him this past season.

SUDEIKIS: Oh, the one with Bieber where Taran’s character is the brother. The “glice” thing.

KEATON: Yeah. I just thought, There’s no way I could stay in that character without laughing.

SUDEIKIS: I mean, my joke about barely ever breaking on SNL is, “Well, I don’t find the show funny. That’s why I don’t break.” [Keaton laughs] But the truth is that whenever I do break, I just break in character as if what’s happening is ridiculous instead of hilarious. So you laugh that way and try to cover it. You bite your cheek, you bite your tongue … But during improv shows, I lose it all the time.

KEATON: Well, you’ve been in good company with that crew on SNL. It’s interesting, though, because from where I’m standing, this generation of comedic performers that you’re a part of seems so much healthier, both psychologically and emotionally, than my whole world. I came up with a lot of really fucking funny people—and good and nice people who are friends. But, by and large, you guys seem much more generous with each other and much less angsty and crazy and competitive … At least it looks like that to me. I could be wrong.

SUDEIKIS: You know, one of the great things about SNL is that it’s been around for almost 38 years, which is basically as long as anyone on the show has been alive. So you have people who have been there forever. And then when you hear about something or read one of those books, like Live From New York [an oral history of SNL by Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller (2002)] or the one by Jay Mohr [Gasping for Airtime: Two Years in the Trenches of Saturday Night Live (2005)], where they talk about it being competitive or dark and SNL as a microcosm for show business … The reality seems so much kinder than the versions of generations gone by.

KEATON: Why do you think that is?

SUDEIKIS: I don’t know. I did a panel for The New Yorker with most of the other seniors on the cast—Andy, Kristen, Kenan [Thompson], Seth [Meyers]—and this older woman brought up the writing staff of [1950s TV variety show] Your Show of Shows. She was talking about the animosity that existed there in reaction to how all of us on stage were finishing each other’s stories and laughing with one another and complimenting one another. She was like, “Don’t you think that the agitation and aggravation that the famous writing staff of Your Show of Shows experienced actually helped make these iconic careers that many of them had?” And we were all like, “I don’t know if it does help.”

KEATON: I always used to say that one of the reasons I was never a big hanger-outer is that I never wanted to catch that particular disease. I want to enjoy what I do and be a happy person and be a generous person, and it seemed like once you got too far into the fat, you were kind of cooked, and I just didn’t think that it was worth it. I had lunch with Alan Arkin once and he told me, “I want a big life and a nice career”—as opposed to a huge career and an okay life. I also think that, in terms of your generation, the parents changed. I mean, I had really nice, healthy parents, but I was embarrassed when I realized I was going to be an actor. It was probably like a feeling of coming out of the closet when I admitted that maybe I wanted to do this …

SUDEIKIS: I think you’re right. I don’t know if the idea of a career in show business or in the arts in general was looked down upon as much as by baby boomers as it was by their parents. I love that Alan Arkin quote, though. It makes total sense to me. John Wooden has a great quote that’s like, “Don’t let making a living prevent you from making a life.” Similar idea.

KEATON: You know, I was doing somebody else’s movie recently—I just had a small role—and they asked me, “What are you working on? What are you doing?” And I said, “Here’s what I do: I wake up in the morning, I grab my coffee and my New York Times, and I read that, and then I go to a place where I start laughing at about 8:30 in the morning, and I laugh till about 8 o’clock at night, and then I go home to a nice hotel, and I go to sleep, and I wake up and do it again the next day.” That’s how good this job is.

SUDEIKIS: Yeah, and a lot of times, there are tremendous salad options, too.

KEATON: That’s the real truth.

SUDEIKIS: Let’s be honest. The most beautiful cherry tomatoes you’ve ever seen.

KEATON: Well, I’m glad we did this.

SUDEIKIS: Me, too. I didn’t know that there was a little chunk of change coming your way, though. I assumed I was going out-of-pocket for this …

KEATON: Like $47,000.

SUDEIKIS: Gee, man. That’s a lot.

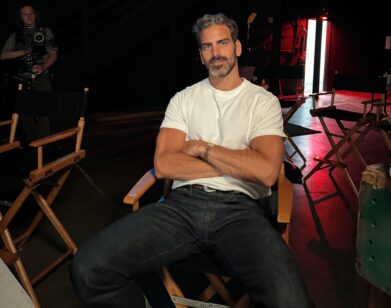

MICHAEL KEATON HAS APPEARED IN FILMS SUCH AS BEETLEJUICE (1988), BATMAN (1989), AND MR. MOM (1983). THIS MONTH, HE APPEARS IN CLEAR HISTORY ON HBO, AND WILL STAR IN THE FILMS ROBOCOP AND BIRDMAN, BOTH DUE OUT IN 2014.