James Toback Is Ready

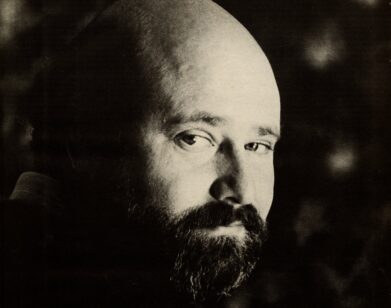

ABOVE: ALEC BALDWIN (LEFT) AND JAMES TOBACK (RIGHT) IN SEDUCED AND ABANDONED.

No one, it seems, is ready to die. Not Bernardo Bertolucci, Jessica Chastain, Martin Scorsese, Diane Kruger, James Caan, Ryan Gosling, or the plethora of film financiers that James Toback gleefully asks in his new HBO documentary, Seduced and Abandoned.

Ostensibly, Seduced and Abandoned is about the hoops a filmmaker must jump through to get funding for a project. Director Toback (Fingers, Love & Money, The Pick-Up Artist, Tyson) and actor Alec Baldwin want to remake Last Tango in Paris as Last Tango in Tikrit and set it in Iran in the early 2000s. Baldwin will star in a version of Marlon Brando’s role and Neve Campbell (or if not Campbell, whichever young actress can get the film made) will play his lover. Toback and Baldwin want 15 to 20 million dollars. The billionaires milling around Cannes are willing to give them four—possibly five—million dollars. Negotiations reach a stalemate.

When the film premiered at Cannes in May, the pair maintained Last Tango in Tikrit was a genuine project. When we meet Toback in New York some months later, however, he makes no mention of it. Instead, he insists that Seduced and Abandoned is really about the ephemeral nature of human life. “As soon as you end what you have to say and you haven’t acknowledged mortality, to me it’s a lie,” he philosophizes.

JAMES TOBACK: So, what do you want to do with the rest of your life?

EMMA BROWN: I’m quite happy at Interview for the moment.

TOBACK: You are? I still love the magazine—I love doing interviews. I’m actually writing a long first-person piece on the conception and making of Seduced and Abandoned for Vanity Fair. But I started as a journalist. I used to write for Esquire and other publications. I think of film as a form of journalism in the way that I think Godard does and this film, in a way, is a kind of film essay. It’s almost a double first-person narrative: these two guys writing and thinking and acting their way through and adventure, which is, among other things, going to explore the whole film universe today against the backdrop of Cannes and something about the mystery of death. Without which, I don’t think anything is reliable or real. It’s implying that that’s not right around the corner at any given moment. I feel it’s your artistic responsibility to remind people in as entertaining and interesting a way as possible that they could be dead in five seconds.

BROWN: You talked about mortality when Hooman Majd interviewed you for us a few years ago—you were discussing William Holden and how, in spite of his fame, no one realized he was dead for several days. When did you first start to think about mortality?

TOBACK: When I was about three. I remember my grandfather had this huge apartment on 77th and Park. There was a terrace that went around the entire building and I was fascinated by the view of Central Park, but I was also fascinated to look down from the height. Now, I couldn’t do it. I would be afraid that I would jump. But somehow, when I was three or four, I thought nothing of climbing over the fence and walking on the outside of the fence around looking down. And I would do it whenever I knew that no one was looking. I knew I wasn’t supposed to do it, so I would wait until I could sneak off. I don’t know how many times I did it. But I knew, even though I didn’t know quite what death was, that if I did it and I fell, I would be dead. I must have asked someone, What would happen if you fell? And that idea, and my aunt had died—my mother’s sister had died when I was three and she was dead and that was looming over the whole family. So there was this idea of death and I knew that I could die just by going over. My father saw me once and he came running and lifted me up and then they put up a big fence so I couldn’t get over. Then I found myself leading a life from the time I was 11 or 12 which, if you looked at with any clinical attachment, was clearly a provocation of death. Do you like to defy death or provoke it?

BROWN: No, not particularly.

TOBACK: No. So if you realized your life was in danger, your response is to retreat, protect, or in some way resist it? Every time I’ve been almost there—in three cases [when] I knew I was going to be there, my response has been, “Wow,” Almost excitement. Not, “Oh no, I can’t believe this or how can I prevent this?” but “Finally.” I won’t say it’s a death wish, because if you really wanted it, it’s not that difficult to do it, but certainly an ambivalence about it.

BROWN: Do you believe in an afterlife?

TOBACK: No, I don’t, I believe that the mind—have you ever done LSD?

BROWN: No, I haven’t.

TOBACK: Have you ever done any brain altering drugs?

BROWN: Yes.

TOBACK: So you know that there is a fundamental question when you get into that of What is the self? What is the I? When you say I, what are you talking about? And if you say that there is something other than you, then you make a case that you’re going to live after you’re dead. Because whatever that is, since it’s not just you as a physical being, that thing you’re talking about may or may not continue on in some form after you. On the other hand, if you say that the “I” is simply located in the three-and-a-half-pound lump of gray matter encased in your skull, then as soon as you’re dead, you’re dead. You don’t exist. Nothing. I can’t believe that that’s not the case. I can’t believe that there’s any consciousness outside the brain. I don’t believe that there’s any in my arm or in my knee or even in my dick, which I often think has a brain and it speaks to me, but I still don’t believe that it speaks to me the way my brain speaks to my dick. It’s funny, the dick is the only other organ that even gives me a hint that there is consciousness anywhere else. Certainly not in my hands. Although I wonder, I used to play the piano—I was very serious about the piano, I just wasn’t good enough to be a concert pianist—but I wonder if really great pianists wouldn’t say that their fingers have a consciousness just as much our brain. But probably we all exist in our brain. If that’s the case, then there’s nothing after. That’s my assumption. I’m surely not worried about going to hell. I have no fears that my behavior is going to be paid back. I think that’s just the way of powerful people keeping unpowerful people in line and rich people keeping poor people poor. I do feel that that’s the key subject of my films: consciousness. What does it mean to lose the self? What does it mean to push yourself to the limit? What do you do, do you break? If you do, can you reconstruct yourself? We’re searching for the ability to create a work of art so we can have something larger than ourselves—so we can have the illusion that before we die, there’s something worth doing that’s larger than our death even though we known it’s ultimately doomed.

And that’s why I read that poem of Updike’s, which is probably my favorite poem about death ever. Have you read Updike at all? Great novelist and a very good poet. He was getting out of favor when he was in his ’70s—got lung cancer. Didn’t whine, didn’t complain. I saw him interviewed by Chip McGrath about four months before he died, [and] his worst-reviewed novel of his life [was] coming out. He didn’t give you a hint that he knew he had lung cancer—that he knew he was going to be dead in a few months—but he wrote that poem in that period of time. And I just think it’s a magnificent poem, and my favorite moment in the movie is that moment with the two of us on the terrace and the thunder is coming down and the lightning and the way Alec says, “I love you.” I wasn’t going to put that in because I thought it was kind of self-serving, but everybody liked it. I just felt that I couldn’t be objective about it. It felt an odd thing to be putting in a movie to have your actor telling you he loves you. Even with the qualification that it wasn’t quite a gay statement. But that moment, the weather, everything conspired to make, all of a sudden, that whole question of the fleeting nature of beauty, the evanescence of things that are transcendent. Then asking people that weren’t expecting it, “Are you ready to die?” Nobody says yes. I mean, I’d say, “Absolutely, I’m eager.” There’s not a single person that just says yes unqualified. Even Roman [Polanski] says, “Well, I’ve never been afraid, and I don’t really want to.” Coppola comes a little closer and he says “No, I’m not going to think about it, it’s just going to come and interrupt whatever I’m doing.” But Bérénice Bejo looked like it the first time in her life that she realized she was going to die was when I asked her. Bertolucci: “Thanks, it’s 11:45.” He hasn’t worked it out religiously yet. Are you ready to die?

BROWN: I don’t think it matters because I’ll be dead.

TOBACK: That’s a good attitude. But if you found out today—how old are you?

BROWN: Twenty-four.

TOBACK: Okay, if you found out today, you’re going to be dead by 10 o’clock tonight. Obviously you’re not happy about it, you have a lot of plans. But what would your deepest response to that be? Would it be one of acceptance? Or what?

BROWN: The idea of knowing that you are about to die terrifies me.

TOBACK: Right, and you’ve never had that happen? You’ve never had a moment where you knew you would be dead in 30 seconds?

BROWN: No.

TOBACK: I have had that with these, rolling off a cliff, drowning and then a guy shooting me in the street from 10 feet away.

BROWN: You’ve been shot?

TOBACK: Yeah, shot at. He missed. But I was sure he would hit me. He was this close and he pulled out a .38.

BROWN: A random person?

TOBACK: No, it was something I had done with a girlfriend of his. It was actually my first line when I saw him waiting in front of the building was, “I don’t blame you, I would do the same thing if I were you.” And then he shot and missed and then I ran and then he continued telling people all over the city that he was going to kill me—shoot me in the back, run me over. Finally, I thought it had gone far enough, so I called him and I said, “If I’m dead, you’re dead. You had your shot. I gave you a shot, and you missed. So unfortunately, as far as I’m concerned, you’re going to kill yourself if you can’t kill me.” Then I never heard from him again, and then he killed himself two years later. Are you happy with your life?

BROWN: Yes.

TOBACK: Do you want to make movies?

BROWN: I don’t think so, no.

TOBACK: You don’t want to write them?

BROWN: No, I would like to write other things. When did you first make the connection between film and mortality? When did you discover the Norman Mailer quote that appears in the film—”Film is a phenomenon whose resemblance to death has been ignored for too long”?

TOBACK: Well, Norman was my mentor. Norman and Dostoevsky were my two literary mentors. One dead, the other alive. And I became very close to Norman. When I read it, which was when it was first written, it was actually an essay that was part of the intro to the script of Maidstone (1970), a movie he made. Another part of the introduction was my Esquire article, which had documented it. So I was joined at the hip with that article and that quote. It was one of those things that Norman would say or write, particularly write, that once I would hear or read, I would realize, that’s what I’ve always felt. But I didn’t actually register it until I read it. That, to me, is when you have a really great writer of influence in your sphere—when you are not just agreeing, but when you actually are feeling he was reading my mind and he articulated what I was thinking in a way that was better than my fuzzy non-articulation of it. For days afterward I was dazzled, almost embarrassed that I hadn’t thought of it because it became so obvious to me. It affected the way I watched film. It also affected the way I made movies, because The Gambler, Fingers, Exposed—most of my movies have scenes, if not the very essence, that illustrate that point. And I wonder how much of that was the result of the lingering effect of that thought in my mind.

BROWN: You don’t find it alarming to have someone read your mind in that way?

TOBACK: If it were more than one person, I would. If it were someone who I wouldn’t consciously admire tremendously and if it were not someone who was much older than I was. There are all these qualifications. And if were someone who I didn’t like and didn’t admire me. I almost felt, for me to be okay with my feelings about Norman, he had to write some really flattering things about movies I made when I started making movies. And he did. In fact, I insisted with my first three films that the movie company use quotes that Norman provided me with, which they didn’t want to do because they were like, “Who the fuck cares who Norman Mailer thinks? We’d rather have a schmuck from the Associated Press who has a normal film review to write. Norman’s not a film critic.” I said, “I don’t give a fuck, you must use Norman Mailer’s quote!” It’s a kind of poetic cycle that has to be finished.

It was as if we had almost shifted roles—one night he called me up and said, “I really need to see you right now, can you meet me for dinner?” And I said yeah, and I had my own similarly wild life. Probably wilder than Norman’s, and Norman’s was pretty wild. He used to like hearing stories about my life, but he was rather cautious about what he would say in his own life. Even though people thought they knew him, he didn’t talk about personal stuff. I met him for dinner and he confessed that his wife had left him because she caught him in a lengthy affair that he had. The first thing she did was immediately fuck somebody else in retaliation and then left him anyway, and he was utterly devastated and disoriented by it. This was his seventh wife or sixth wife, and he clearly was not ready to start another world with another woman. As I sat there, I realized he’s trying to get from me some way of dealing with the pain he’s in. And I thought, this has been, tonight, a complete role reversal. Not that I ever went to him for that purpose, but he was here coming to me to find out how to deal emotionally with a devastating experience. I actually helped a great deal. I told him stuff that, later on, he told me helped him to survive in some equilibrium for the six months before she in fact did come back and they had a reunion, which lasted until he died. But that made it all okay. To have that kind of reverence for someone who isn’t giving you something back, then you’re in a fucking fan club mode and then I’d rather blow my brains out. If your mission on earth is to be the part of someone else’s fan club, I don’t want to be around. That’s a truly embarrassing state of existence. Or even worse, someone who doesn’t like your work.

SEDUCED AND ABANDONED PREMIERES TONIGHT, OCTOBER 28, ON HBO.