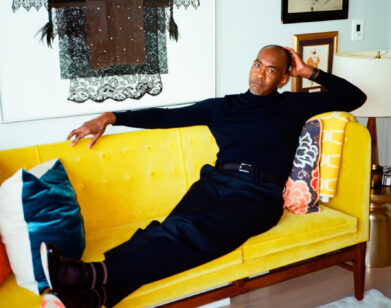

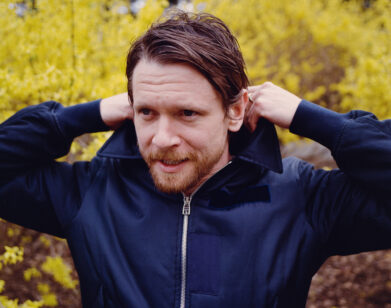

David Armstrong Interviews James Oakley

For over six years, director James Oakley’s first feature film lingered in limbo. Written by Alex Michaelides, Devil You Know is an aesthetic mystery; a tale in which familial loyalty and rivalry are indistinguishable. Lena Olin plays Kathryn Vale, a former screen legend who retired following the very suspicious death of her wealthy husband. Vale is surrounded by an inner circle of dependants: her beautiful daughter Zoe (played by Rosamund Pike and, in a flashback scene, by Jennifer Lawrence), an aspiring actress longing for her mother’s career, her sleazy, younger husband, and very attentive her personal assistant. Everyone has a villainous, seductive, mendacious side, and it is difficult to tell who, if anyone, is the victim.

Following an arduous editing process—and a few early hiccups on set—the film was never released. Now, however, it is getting a second life and Oakley can finally rest easy.

In the wake of the film’s release, photographer David Armstrong spoke with his friend Oakley via phone.

DAVID ARMSTRONG: First of all, James, can you just talk a little bit about how this film grew?

JAMES OAKLEY: Yeah. I went to AFI [the American Film Institute] to the directing program and found it very restrictive. Although in hindsight, I probably should not have found it that way. I met my whole team there—the DP [director of photography], the writer, the producer, the set designers—and we wanted to make a feature quickly out of the program. The writer had an idea that seemed interesting. So, we started putting it together.

ARMSTRONG: What was your feeling of urgency about making the film right then?

OAKLEY: Well, you want to work, right? It might have behooved me to wait a while but I was inexperienced.

ARMSTRONG: What were your initial reactions to the script when you read it?

OAKLEY: Well, the initial idea came out of Mildred Pierce and a real love for that movie and wanting to revisit that film in a way. That was the impulse. Lofty ambitions, for sure.

AEMSTRONG: Well, Todd Haynes tried it.

OAKLEY: Whether he succeeded or not I guess is a matter of opinion.

ARMSTRONG: I think it failed miserably, actually. Can you talk a little bit about the initial person who played Lena Olin’s part?

OAKLEY: The film came about because Rosamund Pike, who was getting to be a known actress, wanted to play one of the lead female roles—the daughter. She was a friend of ours, so she came on board. Then we went through this real process of wanting the woman to play her mother to be a really great actress. We went after people that weren’t really gettable. We stumbled into this situation with this actress named Lesley Anne Warren, who had been a star of some sort. We got her. Speaking nicely, it just wasn’t a good fit; the behaviors and the attitudes didn’t match with us. So, we made the decision to let her go after one day of shooting. I didn’t know that that’s a real dangerous thing to do because, when you shut down a production, you’re hemorrhaging money that has already been spent. But I didn’t have that experience. I think it was clear that we weren’t going to get anything shot with her that first day.

We went back to the drawing board and through great fortune found our way to Lena Olin whom I always really was obsessed with. Romeo is Bleeding is an epic performance by an actress, I think. And I just worshipped her.

ARMSTRONG: She was also great in the last scene of The Reader. Some of the times I was on set she was just so gung ho.

OAKLEY: She was so kind and amazing to be around. There’s no way for me to describe a better person to work with than her. We were plagued with production difficulties beyond belief and she rolled with it like you wouldn’t believe! There was maybe a different make-up artist every single day. Some days she would come out looking ridiculous and we would have to sack the make-up artist right then and she not once batted an eye. There was no ego about it at all. She started out working as a kid in a Bergman film in Sweden—her first movie. She’s worked with amazing directors so it was kind of like, “Woah, what am I doing?”

The male lead was this guy Dean Winters who had been on a show called Oz and a couple other things. The other great female was this woman Molly Price, who was unbelievably fun and up for it. And then Jennifer Lawrence.

ARMSTRONG: I remember thinking she was great, but how did that happen? She was just a kid then.

OAKLEY: Yeah, she was a kid. I think it was her first feature. I saw maybe 50 actresses for the role and it wasn’t even a question. She really had it. She’s not really in the movie much, but she was super fun—directorially fun. She was up for anything you asked at a moment’s notice and made it work. It was not a surprise to me at all when she got to be a big actress.

ARMSTRONG: Can you talk a little bit about the whole editing process—how what you initially conceived of changed during that?

OAKLEY: There was an interest in playing the way the narrative was told. Alex [Michaelides] wrote it from two points of view and you kind of switched—the whole movie switched POV in the middle and then followed the Lena character and kind of retraced the whole steps of the film. That was something that I had never seen really done—or done well—and there’s a reason for it. I found that out in the editing room with this film–it really didn’t work that way. I went to London to edit for maybe a year, trying to make it work [but] it just didn’t really come together from that point of view. Then I went to L.A. to re-edit with this woman named Anne Goursaud who had edited for Francis Ford Coppola. The editing process stretched on and on and it became clear to me it didn’t really come together at all that way.

ARMSTRONG: It is really rare, but All About Eve is a little bit like that because the only way you understand it is by voice-overs. People try to do it and it can be incredibly confusing.

OAKLEY: The tension kept dropping. At the end of it, tension is the most important thing in a film. It’s everything. And there was no tension.

ARMSTRONG: Looking back on the whole experience, what are the pluses and minuses you see now?

OAKLEY: It was like a really long film school. It’s a great way to learn how to make a movie but it’s a super painful, expensive one.

ARMSTRONG: You really only learn to do something by doing it.

OAKLEY: If you’re a photographer or writer, you can do that in a cheaper way. But a moviemaker, the amount of people involved. I guess that’s changed a lot with technology, but it’s super expensive and you don’t get that many chances.

ARMSTRONG: But still, I think you do learn more from the things you do that don’t actually work. When Chris was interviewing Robert Altman and I was doing the photos, they asked him which of his films was his favorite. He asked me if I had any children and I said “no” and he said, “If you did, you’d probably be drawn to the most difficult one.” Obviously one of the failures was the one he liked the best.

OAKLEY: Yeah, totally. I think that perspective that Altman has is probably gained through a lifetime of filmmaking. It’s hard to look back on a trouble film experience. Maybe time will make it easier to appreciate it. [laughs] I’m only talking about the experiences making it I’m not really talking about the outcome of the film. That’s not really up to me to think about at this point.

ARMSTRONG: At what time was it did you realize you wanted to make films?

OAKLEY: My grandfather was a commercial and television producer. He made a bunch of TV shows. When I was a kid, I was always on the set. It wasn’t a conscious aspiration, it just was. There wasn’t another option in my mind. And I started watching movies—like, two a night—since as early as I can remember. I was always watching movies with my grandparents. I kind of lived with them when I was kid.

ARMSTRONG: And you went through a period later of the New Wave French cinema and what was going on in Italy in the ’60s and ’50s?

OAKLEY: Yeah—that kind of wanting to educate oneself about film history. Then I went to NYU cinema studies for film school, so that was four years of intensive theory and studying everything like a year of Goddard—all that sort of stuff. Which maybe isn’t so good for a filmmaker. It makes it a more of intellectual approach. Maybe a true genius can approach film that way and make it great, but I think it makes a harder for just a novice like me.

ARMSTRONG: I know that you like a certain kind of melodrama—Douglas Sirk, [Rainer Werner] Fassbender—the level to which they can take that, which is very different than the New Wave. Who were your primary influences? Who did you love the most?

OAKLEY: They’re always the same and they still have not changed. Fassbender, obviously, is one of the greatest, genius storytellers of movies of all time along with Robert Altman. I still highly regard Brian De Palma as a visual storyteller. David Lynch also was a huge aspiration for me. But I think that my love of those filmmakers also was, in some ways, super detrimental; if you’re so influenced and so loving of something then how do you find your own way to make something? Unless you’re super formed it’s a long road to find out. That kind thing about killing your idols is important.

ARMSTRONG: Do you get inspiration from other art forms as well as film?

OAKLEY: What’s so interesting about a movie is the all-encompassing nature of it—it includes all the arts. You have to be thinking about music, soundtrack, paintings for your compositions and theater, novels, storytelling—all of it.

ARMSTRONG: What do you think about people who do a production without ever having read the book?

OAKLEY: [laughs] I wouldn’t approach it that way. I tend to think you should know as much as you can about something you’re doing.

ARMSTRONG: [On the other hand] it seems like Todd Haynes sat on Deconstructing Mildred Pierce until there was nothing that even had any wit left in it and that’s almost worse. It’s like having a dramateur work on a play until it’s dead.

OAKLEY: There has to be a lot of room for the other to enter. Because it’s so collaborative—really surrounding yourself with the best people and best material. It’s managerial

ARMSTRONG: I think maybe I just don’t like to collaborate. Talk about your new script and what that film is going to be and how you’ve gotten into the idea of a romantic comedy.

OAKLEY: I’m going into production this fall on a script I’ve been writing for the past two years with Alex. It’s not a romantic comedy it’s really a full on slapstick comedy. It’s probably the best experience I’ve had creatively so far. Through making Devil You Know, it was like “Okay, I’m not this. I’m not this type of filmmaker. What kind of stories interest me to tell beyond anything else?” We wrote this thing that was super right, super fun—kind of like a dessert. A great movie to watch on an airplane. I don’t think I would have been able to write that without everything else that has happened, for sure. Again, it’s going back to your influences and also what you actually like to watch. You could be super into Fassbender—and I’m obsessed and influenced by [him]—but it’s not really what you’re going to sit down [and watch]. I know you like to sit down on a Saturday night and watch that.

ARMSTRONG: A good suicide film? [laughs]

OAKLEY: You could sit down and watch a good suicide movie all weekend! [laughs] But I’m drawn to a lighter sort of film.

ARMSTRONG: How do you see the current state of filmmaking? Do you even think it has changed? What is influencing how films are made?

OAKLEY: I think it’s such a massive transition time for movies. I think television has supplanted movies with its storytelling. TV’s become novelistic; the seasons are involved in this epic storytelling that movies can’t go. You have two hours, max. Television becomes such a part of your psyche and your life. Movies are not so interesting anymore, to me—the blockbusters. [The] three-act structure of movies is just super limiting. I’m not so interested in independent cinema nowadays; there’s not many things that I’m dying to see.

ARMSTRONG: But I think that’s because there isn’t really independent cinema. Like everything, it’s been co-opted and that started with American Beauty—a commercial film that was made to look like an independent.

OAKLEY: It’s also this deep, humanistic filmmaking—no matter what genre, there’s [a] humanistic redemption that you have to have in there that I think is really boring.

ARMSTRONG: I agree, but I think the films like Blue Valentine—there is no redemption. That’s what life is like, that’s it. No one is redeemed. Everyone just ends up hurting. But they’re few and far between.

DEVIL YOU KNOW IS NOW AVAILABLE ON iTUNES.