in (dreadful) conversation

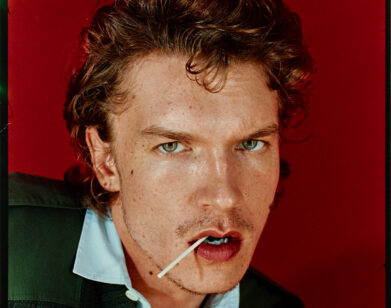

Hugh Grant and Donald Sutherland Enjoy a Perfectly Dreadful Conversation

If there is a downside to achieving mega movie-stardom by appearing in one of the most beloved romantic comedies of all time, it’s being typecast. One imagines the career crossroads that Hugh Grant found himself facing after he starred opposite Andie MacDowell in Four Weddings and a Funeral, the 1994 romantic comedy that showcased all the reasons to fall in love with the then–little-known male lead: There was the floppy hair, the charming caddishness, the handsome prep-school demeanor, the posh British accent, and the winking, biting humor that suggested he could help your grandmother with her groceries while laughing at a dirty joke. Audiences immediately wanted more cinematic dates with Grant, and the threat of rom-com purgatory loomed.

By the time Four Weddings and a Funeral “introduced” Grant to the world, he had already distinguished himself as a serious actor in films such as the 1987 Merchant Ivory production of Maurice and in Roman Polanski’s 1992 drama Bitter Moon. He’d also already mastered his comic technique by founding a small sketch-comedy group in London. And yet, even for those of us barely conscious in the 1990s, it was impossible to escape tabloid coverage of Hugh Grant, the Heartthrob (and his then-girlfriend Elizabeth Hurley). The actor went on to make blockbuster romantic comedies with requisite blockbuster romantic co-stars, notably Julia Roberts in 1999’s Notting Hill, Renée Zellweger in 2001’s Bridget Jones’s Diary, and Sandra Bullock in 2002’s Two Weeks Notice. By the time he turned 40, Grant had become the ultimate fantasy for most women in the film-going universe. Thankfully, he did not get devoured.

In recent years, the actor, now 60, has shown a dramatically different side to his acting prowess, building a fascinating and rigorous resume by taking on a range of difficult, complicated, morally compromised characters who you might prefer to see stepping out in front of a bus rather than riding off into the sunset. In 2018, he played the closeted, murderous parliamentarian Jeremy Thorpe in the 1960s and ’70s period miniseries A Very English Scandal (for which Grant was nominated for an Emmy and a Golden Globe). Earlier this year, he chewed the scenery—and then spit it out—as a dubious private eye in Guy Ritchie’s heist ensemble, The Gentlemen. This fall, he tackles the role of the dashing, possibly homicidal oncologist husband to Nicole Kidman’s Upper East Side therapist in the HBO murder-mystery series The Undoing. Amid the lacquered backdrop of New York City, Grant juggles charisma and chilliness with dexterity, making him the perfect suspect in a thriller that runs on the unreliability of pretty appearances.

In real life, Grant has been outspoken in an industry that prefers its players to be subdued, if not silent; he has recently taken on the British tabloid press, Brexit, and the Conservative government that currently presides over the U.K. He’s even toyed with the idea of going into politics. But after getting on the phone this past August with the great Donald Sutherland, his costar in The Undoing, for a lively conversation involving “fannies” and “berks,” that might no longer be possible.—CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

DONALD SUTHERLAND: You are absolutely wonderful in The Undoing.

HUGH GRANT: You are the one who’s wonderful, Donald.

SUTHERLAND: I can’t address that. I didn’t see it. HBO told me that it would be best if I started off the interview by saying something nice.

GRANT: Oh, I see. Well, it was a very good opening. I have seen it, and you are brilliant. I’m just fat.

SUTHERLAND: I’m so fucking nervous doing this. You prick! I hate interviews, but you do, too. Anyway, have you got a piece of paper?

GRANT: Do I need one?

SUTHERLAND: And a pen, yes. I want you to write something down.

GRANT: Oh, Christ, hang on. I have one.

SUTHERLAND: Okay. Write down, “True wit is nature to advantage dressed, what oft was thought but ne’er so well expressed.” I think those words perfectly represent you.

GRANT: [Laughs] Well, that’s absurd.

SUTHERLAND: Alexander Pope wrote that at the beginning of the 18th century. I think you’re a wonderful actor, but I read that you don’t like acting. Is that true?

GRANT: Well, I’ve liked it a bit more recently. In the last six years, I’ve almost enjoyed my job, and I’ve always enjoyed the bit afterwards. If you happen to make something that works, and people are entertained and say nice things to you, then that’s just heaven. That’s what we’re in it for.

SUTHERLAND: But you were an actor in rep, at Nottingham Playhouse. To do rep, you have to love acting.

GRANT: There’s a part of me that’s always liked it, but I didn’t really mean to do rep. When I left university, I got cast in a film, The Bounty with Mel Gibson, and I was very excited. I thought, “Hooray, this is lots of money, it’s Tahiti, it’s glamour.” And then just as we were about to get on the plane to go to Tahiti, they said, “By the way, is it true you haven’t got an Equity card?” And I said, “I didn’t know about that.” And they said, “Well, then you can’t come.” I was so disappointed that I set about getting one, and the way to do it then was to go into repertory theater and act in lots of little parts in one season.

SUTHERLAND: That’s what happened to Kiefer [Sutherland, Donald’s son].

GRANT: Is that right?

SUTHERLAND: He was rejected for a nonspeaking role in a film that I was in, where he had to play my son, by the director, who was a piece of shit.

GRANT: Name that director.

SUTHERLAND: I can’t remember his name.

GRANT: Bollocks.

SUTHERLAND: No, seriously. The movie was Max Dugan Returns, whoever that director was. He’s dead now. You acted in college?

GRANT: A bit, but then I got sidetracked by high society.

SUTHERLAND: You were in an all-boys school, yes?

GRANT: Yes, and I played almost exclusively lady parts, if you’ll excuse the expression.

SUTHERLAND: Now, would those have been the labia minora, or majora, or the clitoral hood?

GRANT: No, no, no, Donald. You can’t make those jokes, shush. My best part was Brigitta von Trapp, who I believe is the third oldest daughter in the von Trapp family in The Sound of Music.

SUTHERLAND: She had a line, what was it?

GRANT: She said, “I’m Brigitta, I’m 14, and all I want is a good time.” It got a laugh.

SUTHERLAND: I would think it would.

GRANT: And then I went to university and did some serious Shakespeare plays. In particular, I did Hamlet dressed in Star Trek costumes, which we took to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and played to audiences of between two and four people.

SUTHERLAND: You were Hamlet? Lovely.

GRANT: I thought I was rather good at the time, but no one had told me you have to mean it. So I just recited the poetry rather nicely, but I don’t think I moved anyone. Have you played Hamlet?

SUTHERLAND: You’ve got to be joking. I played Fortinbras.

GRANT: It’s never too late.

SUTHERLAND: Everything is too late for me. You’re quoted as saying you’re a terrible actor. That’s bullshit. You know you’re brilliant.

GRANT: I’ve gotten better, but I have perpetrated some real abominations in the early part of my career.

SUTHERLAND: Have you ever done a Noël Coward play?

GRANT: I don’t think I have.

SUTHERLAND: You would have been wonderful in Private Lives. “Dancing’s a greater dread than having your teeth extracted.”

GRANT: That’s true. I’ve had to express myself through movement in films, and I don’t know about you, but I’ve had to be extremely drunk to do that. When I’ve had to do it at seven in the morning in front of a bored film crew, I’ve dreaded it. I remember attending a dance rehearsal for a film called Music and Lyrics, and they got me Britney Spears’s choreographer to rehearse with. We went to this big rehearsal room, and he said, “Here’s what’s going to happen. I’m going to put some music on, and you’re going to express yourself.” He put the music on, and I just stood there, stock-still, for half an hour. I had no self to express. I don’t think he’d ever tried to teach a middle-aged Englishman to dance. It was a very difficult experience.

SUTHERLAND: What about dancing on Rupert Murdoch?

GRANT: Well, yes. That came about nine years ago. I’ve been moaning about the power of the tabloid press in Britain, and their abuse of power, for years—the fact that they were effectively running the country and choosing our government. Everyone thought I was mad or drinking too much, or a conspiracy theorist. And then it all started to emerge after this terrible Milly Dowler episode, when one of Murdoch’s papers hacked the phone of a little girl who had been abducted, which gave her parents false hope. And suddenly the whole of Britain was scandalized, and it became quite a thing. I was very involved with all that, and still am, because we still haven’t won the war, although we’ve won battles along the way.

SUTHERLAND: You want to talk about film acting?

GRANT: Yes, I want to drone on about it.

SUTHERLAND: Okay. Talk about the difference between acting when the camera is not on, and when it is. GRANT: My torture all these years has been that you go in at the beginning of the day and say, “Let’s just do a mumble through. Let’s do a lineup.” And I’m marvelous in the lineup. There’s no camera. And then you start to shoot it. You shoot the wide shot, and I’m still pretty damn good at that. Loose, relaxed, maybe even amusing. I’m not bad in the two-shot, and superb in your close- up, when I’m off camera. And then toward the end of the day, they say, “Hugh, we’re turning around on you now for your close-up.” And you know it’s going to be the shot they use most in the edit. And the pressure builds as they put the lights up, and an hour later, you’re shoved in front of the camera. Time’s running out, we’re losing the light, someone comes in and adjusts your makeup, which is extremely irritating, or yanks up your trousers, splitting your cluster and making you yelp. And suddenly it’s, “Action,” and you find that under the gun, you have none of the looseness, the colors, the textures, the humor that you had all day. That has been a torment all my film life. Do you feel that?

SUTHERLAND: No. But I did a film with Vanessa Redgrave, and finally I had to say to the director, “Listen, shoot me last,”because I would do my close-up, and then she would do hers, and her close-up had nothing to do with anything that she’d done before. It was so precise and specific. I’m nervous all the time. For me, the camera’s either a voyeur or a lover. If it’s your lover, it shares your soul, you give it your virginity over and over again, and it’ll embrace your heart. If it’s a voyeur, it’s a fucking paparazzi.

GRANT: I know that Anthony Hopkins goes and strokes the camera every morning and says “Good morning” to it.

SUTHERLAND: I kiss the lens.

GRANT: The process of filming has gotten easier now that there’s usually more than one camera around. And very often, you can persuade directors to shoot two close-ups at the same time, which means you can’t get your Vanessa Redgrave problem.

SUTHERLAND: [Laughs] But then you get badly lit. That was Audrey Hepburn’s problem.

GRANT: You’re so vain.

SUTHERLAND: It’s true. In Robin and Marian, Richard Lester shot with two or three cameras, with Sean [Connery] and Audrey Hepburn, and she was used to being lit to make her look beautiful, which you can’t do with two or three cameras.

GRANT: I’m not sure we need that beauty lighting anymore.

SUTHERLAND: I need all the help I can get. You’re quoted as saying, “Comedy is probably a way of dealing with anxiety, sometimes a way of dealing with pain.”

GRANT: I don’t know all the bullshit I’ve said. God knows what I say in interviews.

SUTHERLAND: Bullshit? You said it!

GRANT: But I’ve said all kinds of crap just to get through the half-hour. But I definitely do think that the best comedy deals with pain, that it deals with something nasty and alleviates it. That’s the comedy that hits home. I think that’s the most full-throated laugh you can get.

SUTHERLAND: Yeah.

GRANT: I’ll try to think of an example. You know all those films I did with Richard Curtis, like Notting Hill and Love, Actually and Four Weddings and a Funeral? They’re comedies, but I have a feeling that they worked because they were dealing with a quite painful love. And it was real, because Richard Curtis, although he’s a very funny guy, has suffered more than most people I know, on the horns of terrible, unrequited love affairs. So for him, those scripts were a way of dealing with pain.

SUTHERLAND: Four Weddings and a Funeral made $363 million, and it’s reputed that you have 10 percent of that.

GRANT: No, I wish I had.

SUTHERLAND: I just made that up, Hugh.

GRANT: Oh, well, it would have been so lovely. I had what are called net points, which are known in the business as “not” points, because you never see them.

SUTHERLAND: Do you suffer from stage fright?

GRANT: About once a movie.

SUTHERLAND: Care to elaborate?

GRANT: Out of the blue, when I’m doing a scene that’s not very challenging, I’ll be overcome with shocking nerves. I start shvitzing from my armpits, and the makeup people can’t bring sponges fast enough to get rid of the sweat from my face. I can’t breathe, I can’t remember my lines, and it’s extremely embarrassing. I went to see a shrink, and he told me that the answer is to go away and do a lot of press-ups, so that’s what I do. I manage it better now than I did. But you really cheered me up by telling me that you’re so nervous before day one of a shoot that you actually throw up. Is that true?

SUTHERLAND: The night before, I always throw up. I very nearly threw up before this interview.

GRANT: [Laughs] How fascinating.

SUTHERLAND: What about language? How do you deal with the cultural contrast between the American lexicon and the English one? What I mean is, if you finger someone in the United States, it means that you surreptitiously point out a criminal to the police. Does fingering someone mean the same thing in the U.K.?

GRANT: [Laughs] I do remember having dinner with Demi Moore once, and she was complaining about the chair she was sitting in. She said she had a really sore “fanny,” and I was very surprised she would say such a thing. The first time I ever went to Los Angeles, I was checking into the Mondrian hotel, and they said, “How are you going to take care of your room?” And I said, “As well as I possibly can. I’ll try and keep it tidy and everything.” It’s harder than one thinks.

SUTHERLAND: In America, when a man’s behaving badly, they call him an asshole. In the U.K., he’s called a “berk,” right?

GRANT: Yes. Or an asshole.

SUTHERLAND: Berk is Cockney rhyming slang for that much cherished Middle English word “cunt.” Right?

GRANT: That’s news to me.

SUTHERLAND: Oh, really? Berk applies to men. A “Berkeley Hunt” cunt is a man. A “Granny Grunt” cunt, sometimes called a “fanny” or a “jack and dandy,” is a woman. It’s spoken with affection, and it pertains specifically to that exquisite opening that leads into a woman’s reproductive organs. It’s an old English lesson.

GRANT: [Laughs]

SUTHERLAND: Do you care about being first up or second up in an over-the-shoulder shot?

GRANT: I think first up is better. There are people who just don’t give you off-camera what they’re going to give on-camera, at all. I won’t name names, because I can’t be bothered with the stress afterward, but it’s a surprising number who just don’t really care about doing it when they’re not on camera, and it does screw you up.

SUTHERLAND: You’ve talked about real life and synthetic life. Can you elaborate?

GRANT: I feel like I’ve had too much synthetic life. I used to say that when people asked why I’d done all this political stuff with Murdoch, and then more recently when I made a huge effort to try to prevent this latest British government becoming the government, because I thought they were lethal, really, and I think I’ve been proven right about that. People ask me, “Why bother to do that?” And I say, “Although it’s stressful, it’s a lovely relief, after decades of creating synthetic life, to be dealing with real life.” It’s got some texture. You get your teeth into it, and people are not nice to you. In our world, too many people are lovely to us. And I have found that in the world of politics or campaigning, it’s brutal out there, and it feels quite bracing.

SUTHERLAND: How did playing Jeremy Thorpe [in A Very English Scandal] affect that?

GRANT: Well, I certainly recognized in Thorpe what I had found in many, many politicians that I’ve dealt with, which is that the propelling motive for them getting into politics was vanity, and that whoever said politics is show business for the ugly was, in fact, correct. These were people behaving exactly like spoiled Hollywood actors, just without the acting. That is the compelling motive behind Trump and behind Boris Johnson. Pure vanity.

SUTHERLAND: Did you read Mary Trump’s book [Too Much and Never Enough]?

GRANT: Funnily enough, it’s sitting right next to me. My mother-in-law just gave it to me.

SUTHERLAND: It’s a terrific book. What about character? Does your character ever take you over?

GRANT: Only one. When I was at school, I would do a very good impression of our chemistry teacher, Mr. Hammond. He spoke with a slight Halifax accent. It was very popular. And I have found that ever since, in the decades that followed, whenever I’m stuck in a role and haven’t quite found how to play him yet, Mr. Hammond pops out. So yeah, he has haunted me.

SUTHERLAND: Every once in a while, my characters take off in the middle of the film. They don’t say what they’re supposed to say, they lead me around by the nose.

GRANT: [Laughs] I’ve heard that about you.

SUTHERLAND: Yeah, fuck you.

GRANT: Susanne Bier told me about various times you did that on The Undoing, and they made me laugh and laugh and laugh.

SUTHERLAND: Do you ever want to change the script? Like, for your character. I change the text on every film. I write it down in Final Draft, send a copy of it to the writer, they approve it, and then we send it to the director. I don’t interfere with anybody else’s lines, but I try to make the lines that I’ve been given fit my mouth.

GRANT: I basically agree with you, but it’s a thorny business, because if you’re good at it, it’s fine, but some actors are not good at it. Or they’re selfish, and suddenly the new scene arrives for the other actors, and it’s got pages of dialogue for the person who’s rewritten it.

SUTHERLAND: I don’t change the intent of the scene, just the words in my mouth.

GRANT: It depends on the film, and there are films where I’ve added a helluva lot. And there are films where I haven’t. But there’s a weird thing where if one forces oneself to say the line as written, even though it doesn’t feel entirely comfortable, it can actually come out better. The older I get, the more I realize that.

SUTHERLAND: I’m not talking about improvising, you understand. I’m just talking about taking exactly the same words that the writer used, but making them fit my mouth.

GRANT: Listen, I’m really sorry, but I’m going to have to wrap this up, because I’m being dragged out to dinner.

SUTHERLAND: Hugh, this has been a dreadful interview.

GRANT: I agree, it’s been a nightmare. We must never, ever do this again.

This article appears in the Fall 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Grooming: Petra Sellge at The Wall Group

Fashion Assistant: Letizia Maria Allodi

Special Thanks: Chiltren Firehouse