The Real Underground Music of Give and Take

ABOVE: A STILL FROM GIVE AND TAKE, COURTESY OF THE FILMMAKERS

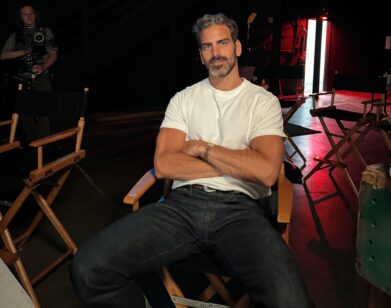

Descending into New York’s underground, independent filmmakers and college buddies Carl Kriss and Chris Viemeister found inspiration in the unbridled passion of subway musicians. Their debut documentary, Give and Take, is a raw glimpse into these subterranean performers’ lives, and most recently won the Audience Award at the SENE Film Festival.

While incorporating a myriad of stories, the film centers on a handful of distinctive characters, including “Saw Lady” Natalia, PhD professor Renard, tragic-yet-talented Douglas, Carnegie Hall musician Ed, and blind seranader Paolo. After meeting Chris by chance on the street, we spoke with both boys about guerilla filmmaking and discovering the unexpected.

MICHELLE ONG: How did you guys meet each other?

CHRIS VIEMEISTER: Carl and I started as production assistants on an independent film set. We really hit it off, in some ways because we both aren’t part of the New York film-school network.

CARL KRISS: Chris likes to say I tricked him into making a movie.

ONG: Why a documentary about street musicians?

KRISS: As a PA, you’re there to follow orders. No one gives you the chance for creative input.

VIEMEISTER: When we were working 14-hour days and taking the subway at weird hours, these musicians were kind of comforting. They broke us out of the mundane and into the present, so we’d stop worrying about what we needed to do next.

ONG: Why do you think street music is important?

KRISS: I think it’s one of the most American art forms. It’s about innovation, improvisation, and pursuing what you love. I hope one thing that came across in the film is that these aren’t just people we should just pass by. Especially in the kind of world we’re living in, they can be admired as examples of courage.

VIEMEISTER: Five million people ride the subway every day and are exposed to this raw art. I feel like for every one person who keeps walking and goes to their job, there are two that stop and say, hey, I want to do what I love. It’s very inspiring.

ONG: How did you choose which people to focus on?

VIEMEISTER: We literally went up to everybody, it didn’t matter if we thought they were good or not. We took out a camera, and if they gave us a nod we’d start to film. It was a prime example of how you never know where a story is going to lead you.

KRISS: We improvised a lot, but gradually got more selective as we saw themes start to emerge.

ONG: What kinds of themes?

VIEMEISTER: I take the subway all the time, and would assume “You just want my money. You’re probably some homeless person.” Filming this, I had to ask myself, “Why am I judging these people who I don’t know?”

KRISS: I wanted to make sure we shot this from their perspective, instead of our preconceived ideas of who they were.

ONG: What was it like to go into the Park Slope apartment of jazz musician Ed, who plays in public parks, and see photos of him with people like Benny Goodman and Roy Eldridge?

KRISS: He was really modest, bringing it up casually, like, “Yeah, I played for five different presidents.”

VIEMEISTER: It was still absolutely surreal to see photographic proof of what he’d been telling us.

ONG: What happened to Douglas, the alcoholic who reminds me of Bob Dylan?

KRISS: I talk to him every other day on GChat! He definitely has addictions that cause him to be reckless and somewhat selfish. He disappeared and apparently got arrested and went to jail for a year. He never told me what for. The first thing he did when he got out was to put an ad on Craigslist for a free guitar, so he’s still out on the streets playing his music.

ONG: Why did you feature so heavily the Music Under New York program?

KRISS: It’s like American Idol for street musicians. It’s so competitive—they get hundreds of applicants and only pick 25. MUNY provided us with a narrative arc: all the drama behind who would get the acceptance letter.

ONG: Do you think the program’s structure is beneficial, or dampens the grassroots spirit of the scene?

KRISS: MUNY gives these musicians a sense of community, which is what they’re looking for by playing in public. If you don’t have a regulatory system, it’ll inevitably lead to fights. But MUNY does support more established musicians who have their acts together. Someone like Douglas is never going to audition.

VIEMEISTER: Without the structure, you’d get a horrible cacophony of sounds, like a steel band in one corner competing with a violinist on the other—which is bad for business.

ONG: What were some of the obstacles you faced while shooting?

VIEMEISTER: Coordination. These musicians would just disappear. The best strategy would be to show up and hang out. Paolo, the blind singer, would have a different phone every other day, so we’d have to leave messages everywhere.

KRISS: Dealing with all these different personalities. We had to adjust ourselves to match the way each musician worked. Also, making your first movie is like raising a child. Figuring out our roles and creative ownership was a very painful process. I’m sure Chris would agree.

VIEMEISTER: No, actually, it wasn’t that painful. I thought we worked it out well!

ONG: How do you think street musicians capture the so-called “spirit of New York”?

VIEMEISTER: Oh man, New York would be a terrible place without them. All these different flavors of people from around the world, who share a mutual love for music. They provide a much-needed outlet and sense of connection to other people.

KRISS: New York is a place where you can get completely lost in, and subsequently found. People like Saw Lady, who was hit by a taxi, or Paolo, who became blind, lost things that mattered a lot to them—but found something they loved even more.

VIEMEISTER: It’s like how Douglas said, “We’re all addicted, man. We’re stuck here. But we love it.”

TO KEEP UP WITH UPCOMING SCREENINGS OF GIVE AND TAKE AT FESTIVALS AND ELSEWHERE, VISIT ITS FACEBOOK PAGE.