François Ozon’s Object of Desire

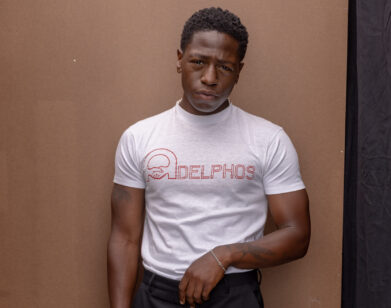

ABOVE: MARINE VACTH AND FRANÇOIS OZON, COURTESY IFC FILMS

Over the course of nearly 20 years, French director François Ozon has produced just as many films, charging his prolific oeuvre with not just the provocative, but also the unexpected. The Cannes regular has served up a high-camp musical like 2002’s 8 Women (with Catherine Deneuve and Isabelle Huppert headlining) as easily as a slow-burning murder mystery set in the south of France (2003’s Swimming Pool, starring Charlotte Rampling, naturally), an austere domestic drama (Ricky, 2009), and last year’s In the House, a tense look at the relationship between a troubled high school student and teacher.

His latest film, Young and Beautiful, which opens today, is a meditation on nascent female sexuality, told through the 17th year in life of Isabelle (startlingly beautiful newcomer Marine Vacth). A bourgeois Parisian teen, Isabelle struggles to establish her burgeoning identity, not through socializing, parties, drugs, or her studies, but through sex. Structured in four parts, one for each season, and each set to a Françoise Hardy song, the film begins with Isabelle, voyeuristically spied through the lenses of binoculars, sunning topless on a beach. The narrative quickly unfolds to the loss of her virginity and entrée into high-end prostitution.

Ozon maintains he knows as little about Isabelle as we the viewer do—her motivations remain opaque, even as she makes her transformation from well-heeled, well-cared for ingénue to a walking, talking object of desire with wads of euros piling in her closet. The pull of the film is Isabelle’s uncertainty, and her search for whatever she seems to be looking for.

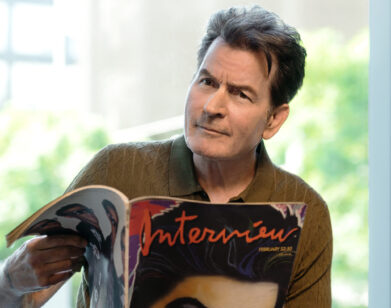

Interview spoke with Ozon last month at the Mercer Hotel.

COLLEEN KELSEY: You received a certain amount of press on how a lot of people have considered this film to be an extreme depiction of female teenagers, but I don’t really see it that way.

FRANÇOIS OZON: It’s a special story. It’s funny how people want to sometimes think that it’s a film about all adolescents, but it’s just the case of one girl. It doesn’t mean all the adolescents are like that, of course.

KELSEY: Why did you choose a young woman as the protagonist for this film?

OZON: The first idea was to have a young boy and to explore the sexuality of boys. But, I realized, with a boy doing prostitution, of course it has to deal with homosexuality. And I had a feeling it was too much for the film, you know, sexuality, prostitution, adolescence … there were too many films for one film. I didn’t want to make a very dramatic movie. In a certain way, I wanted to do a girly film. I wanted to make something sweet, pink. With a boy it was too dramatic and too heavy. I had a lot of pleasure with the boys in In the House, I said, “This time I will do [a film] with girls.” Sometimes it’s easier for me to do films about, and with, women, because I have more distance, I’m more lucid. When I met Marine, I was sure it was a good idea because she was amazing; she was beautiful, she was profound, and she was mysterious. I didn’t have the answers. I had many questions, and the film was about questions. I thought she would be perfect to express all those questions.

KELSEY: You’ve worked with a lot of teenager narratives before—is that a period of life that you’re interested in exploring, the turbulence of that time?

OZON: Marine’s supposed to be 16 in the film—now she’s 21. You’re so much more mature. You have learned; you are someone else. The fact to have this small distance with your adolescence is very good because she knows it’s not herself. I’m not stealing your things, you know? I’m not a pervert, you know, taking a youth. This small distance is very important, especially for such a part, which is very heavy to carry.

KELSEY: A lot of teenagers get into drugs or alcohol to test themselves. How did prostitution come up as Isabelle’s—not her vice, but the way that she tests her limits?

OZON: It’s easy today. It was not easy when I was a teenager. But today, with the new technology, with the Internet, everybody can do prostitution with two clicks. During the period of Belle du Jour, it was a very strong decision to go into the profession, but now, if you need a little bit money, you go on a website and you say, “Can I have 50 dollars?” It’s easy! I wanted to show these facilities.

KELSEY: Isabelle’s motivations are not so clear. There’s a sense of mystery there.

OZON: Yes. I think there are many motivations, but she’s not able to express them, because she doesn’t know herself .

KELSEY: Do you think in her case, it’s not the best thing to be young and beautiful? That, perhaps at a young age, you cannot be totally aware of the power that you hold over other people’s desires?

OZON: I think young people are aware, more than when I was young. There is such an obsession in the media of young people, about their beauty. The magazines and the fashion, all these kinds of things. They know that, and they use this power. I think in certain ways Isabelle knows that. But she carries her beauty like something heavy. Speaking with a shrink, he said to me, there is a kind of syndrome of girls who want to dirty themselves. They have the power. They control everything.

KELSEY: Do you think there’s a moment in the film where she becomes aware of the power that her beauty holds to elicit desire in other people, and harnesses it? In the beginning, it’s not so clear. She goes out with Felix, the guy at the beach, she knows that she’s beautiful, but she’s not completely in control of herself and what she wants.

OZON: I think what interests me with the scene with Felix is the fact that speaking with many young people, they act like their virginity is something you have to turn the page very quickly on. “It’s done.” I think it’s a little bit what Isabelle does. She chooses this German guy, he’s cute, he’s nice… she’s not in love with him, but she wants to do it. And he’s not a good lover. [laughs] She’s not able to have a good experience. Actually, for everybody, the first time is never a good time. It’s always a disaster.

KELSEY: What was your approach to filming the sex scenes, especially when Isabelle’s with clients? Illustrating sex on film can be tricky. How did you want to frame those scenes, not only for your actors’ comfort, but for the mise-en-scène?

OZON: It was important to show that the sex scenes were not important for her. The sexual act doesn’t interest her. Except with the old man, because something else happens between the two. There is an exchange between the two; there is tenderness. He is able to watch her differently than the other men. She’s not just an object of desire. Her own desire can exist. He tried to give her some pleasure, which is not the case, I think, when you are the prostitute… you don’t want to be coming. [laughs] This man is doing things differently. He’s able to watch her differently. With him it’s different. But in a way, I think she’s looking for her own desire in a very naïve way. She thinks, “Being in the desire of others, maybe I will discover my own desire.” But she’s totally wrong, I think.

KELSEY: I found the relationship between Isabelle and her mother very interesting, especially since her mother is progressive; she seems sexually fulfilled. But prostitution is still taboo to her.

OZON: Of course. Everybody would be shocked. Isabelle is in a kind of perfect family. They have money, they are progressive, they are clever. She’s in a great high school. She’s beautiful. Everything seems perfect. But actually something is missing. I had in mind a case close to my family, friends of my parents, who seemed to be the perfect bourgeois family, and a young boy, who when he was 17, committed suicide. It was such a shock. The parents didn’t understand. Nobody understood why he did that. Everybody was exploring his life, trying to understand what the problem was. Everybody had a feeling that this guy had the perfect life: he was beautiful, he was clever… but he did that. I had that in mind, about Isabelle, for the parents to see adolescents like aliens.

KELSEY: But I think she finds a bit of relief at the end of the film when she meets Charlotte Rampling’s character, the wife of one of her clients.

OZON: Of course. For me, there is a resolution. When I spoke with psychoanalysts, they confirmed to me that the most neurotic relationship is always between mother and daughter. The cliché is to think it’s because of the father, the absence of the father. I had this intuition that I had to end the film with another woman, but not the mother, because the dialogue is not possible at this period of their lives. But a neutral woman, someone who’s outside… she’s not totally out of the story because she’s the wife. But she’s someone who has a distance and who is able to say some words which are helpful for her own evolution and exploration in sexuality and identity.

KELSEY: Something about the pairing of them, I felt that it was very easy to see Marine mirrored in Charlotte. Something about their freckles. They have a similar look. Was that important in casting her?

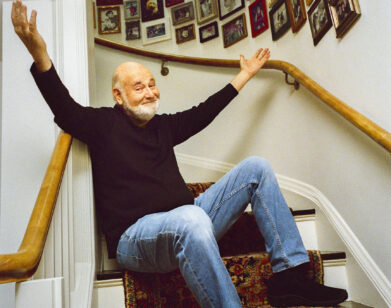

OZON: They are very similar. When I met Marine and when I decided to cast her for the part, it was obvious that Charlotte would be the woman at the end. It could have been Catherine Deneuve, but it would have been too funny, the old Belle du Jour coming back. [laughs] It would have been too much. But Charlotte and Marine are exactly the same kind of actress. Very mysterious, very wild, un peu sauvage.

YOUNG AND BEAUTIFUL IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TODAY.