Elizabeth Taylor: Chapter Two

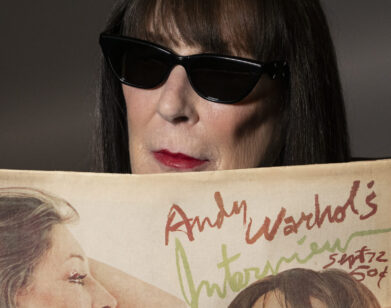

Elizabeth Taylor was among the last of the great American golden-age film legends, and the news today of her passing has brought great sadness upon the entertainment industry. On the occasion of the February 2007 issue of Interview devoted entirely to Elizabeth Taylor, then-editor Ingrid Sischy executed an extensive interview with the actress and icon—and today, to honor Taylor, we’re republishing that interview in installments, of which this is the second. To read the first, click here.

INGRID SISCHY: So where does your spirit, your clear belief in the importance of freedom come from?

ELIZABETH TAYLOR: Rebellion, I think. I was so strictly brought up that the only time I could get away would be on my own pony. I could ride wherever I wanted on my godfather’s estate in Kent, which was 3,000 acres. It was all walled in and there were no dangers. I wasn’t brought up to be afraid of anything.

IS: Is that where the fearlessness comes from?

ET: I think so. I’d be thrown from my pony and climb back up, and we’d go off again—the faster the better. She was a Newfoundland pony, a wild thing—a real wildcat.

IS: Is that where you learned your wildness?

ET: I think so. Being on her back and going like the wind wherever I wanted to. It was the only time I could do exactly what I wanted. And that was what I wanted—to be on my horse and be part of her, Betty.

IS: Betty?

ET: Betty was a wild girl. I think she came with the name. My godfather gave her to me.

IS: So he must have known that a pony would be a great thing for you.

ET: Yes. I used to dance for him, and he’d have people over to watch me dance. I would totally lose myself in the music and be a gypsy. I would go wherever I wanted to in my head—wherever the music took me. My body followed.

ET: I was just an old little girl, a different kind of child.

IS: Weren’t you only nine when you made Lassie, Come Home, your first movie?

ET: Yes. But actually, before that I did a terrible little film at Universal called There’s One Born Every Minute [1942]. That was with Hugh Herbert and I played an American brat. I hated it, so I had my parents make a deal with Universal that we had a two-way contract—they could fire me if they wanted, and I could leave the movie if it didn’t suit my psyche.

IS: You knew to do that? That’s sharp, considering you hadn’t dealt with movie studios that much yet. What was it like in Hollywood in the late 40’s and early 50’s?

ET: People were afraid of seeing submarines in Beverly Hills, and everybody had a bomb shelter. It was the thing. People in Beverly Hills would have bomb-shelter parties. Once in a while the kids were allowed to go down and play house in there—it was a totally Hollywood, unrealistic attitude toward the war.

IS: When you were young and working in Hollywood, did you feel like the whole family was counting on you?

ET: No.

IS: You were the one doing the big earning, weren’t you?

ET: Oh, I paid the bills.

IS: From what age?

ET: The minute I started working. Just because people weren’t buying art. It was hard on my father.

IS: When did you leave home?

ET: I left home as soon as I could, when I was 18. I thought I was in love and got married—the press called it Prince Charming and Cinderella. He was a Hilton so I was the poor little Cinderella. And when I got a divorce nine months later I never told the court why, but he was cruel. When he drank it all came out, and I hadn’t seen that before because he was on the wagon the eight months we were engaged. I didn’t have a clue. But I thought, This isn’t why God put me on Earth. We were married in a Catholic church. I had studied Catholicism for almost a year. But when I had to swear in front of the archbishop to be a good wife and all that stuff, I had my fingers crossed behind my back because I didn’t know if I could be a good wife; I knew I was still a child.

IS: Do you feel that you chose to be an actor? Or was it chosen for you?

ET: No, I loved it. Sure, my father hated it—he had made my mother quit the stage when she was 29 and she lived her life vicariously and very strongly through me. And, of course, my dad resented that. It was the end of the idyllic, happy little family that Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal wrote about: beautiful mom, sweet little daughter, brought up in England, and idyllic life. I was no longer a refugee, I was a little girl from England.

IS: When would you say the end of the idyllic life was? A few years after you landed in Hollywood?

ET: When I started making more money than my father, and my mother erupted—that’s when it fell apart.

IS: In the early days would the studio just give you projects? With National Velvet [1944], for example—did you choose to be in that or did they simply tell you, “You’re in this”?

ET: No, I longed to be in it because it was me. That was me. And I chose the horse. He was a wild, thoroughbred racehorse that nobody else could ride and, of course, that thrilled me to the core and made me his and he mine.

IS: Would he go home with you at night?

ET: [laughs] We lived in Beverly Hills. But I went to him. I would ride every morning before I went to the studio. I learned to jump before National Velvet because I just loved the feeling of flying. I could jump six feet bareback and it was the closest thing to being Pegasus and flying next to God. It’s the most liberating freedom-making feeling in the world.

IS: Did you ride all your life?

ET: Since I was 3.

IS: And all the way through your decades of making movies?

ET: Not after my back started giving me trouble. I was born with scoliosis. I have a double curvature of the spine, and it’s forced me to use a wheelchair because the disease has really taken hold. It really saddens me that I can’t ride.

IS: But you can ride in your head.

ET: Oh, yes. And I get away. I get away in my head. I can dream. I can still daydream.

IS: I know you love to travel. Is that part of why it’s great to do a movie—you get to see the world?

ET: Oh, yes. Being able to go on location and see the world was the greatest perk of all.

IS: And you also get to have an instant family.

ET: Every set that I worked on since I was a baby, the grips, the electricians, were my families. When I was a little girl, the grips used to pick me up and throw me around like a bag of potatoes. They’d buy me comic books and candy bars, all the forbiddens. It was wonderful.

IS: Where did they shoot A Place in the Sun [1951]?

ET: Lake Tahoe.

IS: That’s supposed to be beautiful.

ET: And the Paramount lot.

IS: That’s less exciting, but Lake Tahoe…

ET: Oh, it was beautiful and freezing and it snowed and I had to get in the water. They melted the snow. They had burners out all night for days before we could use the water. And talk about cold!

IS: Why didn’t they shoot it in the summer?

ET: We’re talking about Hollywood, dear! [laughs]

IS: They weren’t worried you’d get a cold?

ET: They don’t think about things like that. They save the dangerous things until the end. Just in case you get pneumonia or die. I’ve always noticed how they do their scheduling. The dangerous bits are always the last days of shooting.

IS: Don’t you water ski in the film?

ET: Yeah. And in one scene Monty [Clift] and I are in a raft in the middle of the water. And he has to pick me up and throw me in the water. I had my period and terrible cramps and I said, ” Oh, Monty, don’t, don’t, don’t, oh, please don’t!” He thought I was acting so he goes ahead with a big laugh and throws me in the water. I tried to throw myself back and I scraped myself. It’s amazing the gymnastics you can do when you don’t want to do something. How you can force yourself against all the forces of nature. I threw myself backward.

IS: You landed back in the boat?

ET: Well, I didn’t. But I was back on the raft so quickly. I don’t think my mother noticed, the crew gave me a little tote of brandy.

IS: It’s said that the crews always loved you.

ET: I always loved them. They were my family.

IS: If you had a director and you thought they did not really know what they were doing, how would you deal with that?

ET: [laughs] Well I had such a director. He was a method director. And I’m just an instinctive actress, I’ve never had a lesson in my life. So I didn’t understand all this relate to this, and all that BS. I mean, it works great for some people but it didn’t work for me. I hate to try to be that person in my own skin, in my own way, in my own head, not through exercises or anything else, just by, I guess, belief, concentration.

IS: Imagination.

ET: Yeah, imagination. By making myself that person. So on the film where I didn’t get along with the director, I just decided to not speak to him.

IS: Are you kidding?

ET: No. We didn’t speak during the whole film. The camera crew and I worked out shots and that’s how I got through the film.

IS: Was it a long shoot?

ET: Yes. I hated that film. But the funny thing is, I ended up winning an Oscar for Butterfield 8 [1960]. It tickles me.

IS: When I came to your house once with Bruce Weber to photograph your sweet dog Sugar for a story in Interview, I loved where you kept the Oscars.

ET: In the television room?

IS: Yes. I like that there was respect for them but they weren’t the first thing you saw when you walked in the house.

ET: Oh god, no. I’ve given a couple of them away. Mike’s Oscar, I gave to my grandson who’s so like Mike. He’s studying theater and movies. He is like Mike Todd to the last little hair. His mannerisms, the way he talks on the phone, the way he uses the phone and kind of stalks when he’s talking on it—he’s Mike. And he has the energy and the genius. So I had to give it [that Oscar] to him when he won his first prize from school.

IS: It must mean so much to him.

ET: And I gave a very dear friend of mine my humanitarian award. Because you don’t need an award to be, or not be, a humanitarian.

ET: Next time you and Elton go to Africa could I go with you?

IS: Do you know how much we’d love that?

ET: I’ve talked to Nelson Mandela a lot and he wants me to come. I would love to. I saw the most extraordinary things I’ve ever seen in my life [in Africa], like a baby elephant being born on the edge of the Chobe River. We were in a canoe and we floated over next to them and [our guide] Brian—oh, if I could only find him again—was saying, “This is wrong, Elizabeth.” I said, “It’s all right if we stay still, it’s all right. They’re looking at us and I can see it in their eyes, they’re so gentle; they’re accepting us.” And we got so close I could see the stuff coming out with the baby. And then I said, “Back us away a little bit,” because we were practically in them. Here I am telling Brian what to do. It was one of the most beautiful moments of my life. And [on another occasion] we were following a black-maned lion. We found its tracks, at six in the morning, and we went in the jeep, which has no grating on the roof or anything, We came upon the lion and he was lying down in the dirt path with his head away from us. And he swiveled his head very slowly and looked at us and Brian said, “Don’t look in his eyes.” I said, “I can’t help it, I already am.” And the lion and I looked into each other’s souls and we stared at each other for about five minutes. Nobody moved. Finally the lion stood up and it seemed like he grew, and grew, and grew into this huge creature with his massive black mane that took over half his body, and he turned and looked again at me and let out a roar that shook the Earth and then he very gently padded away. There were poachers on the perimeter of the reserve where they’re protected waiting to catch this magnificent beast. And yet, he trusted me, talked to me, and accepted me.

IS: We’re going to run the pictures Bruce [Weber] took of you with the great big bear. There’s no fear in your eyes in those pictures, yet the bear is humongous.

ET: Oh, I felt no fear. And there was no fear in the bear. At one point the bear put his hand on my hand and then I put my hand over his. [laughs] You should’ve seen his claws. They probably show in some of the photos. He’s never had a manicure. [Sischy laughs] I thought of taking out an emery board but thought better of it.