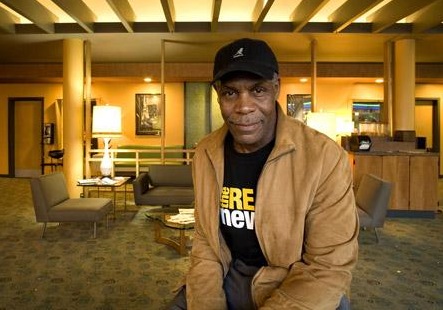

Danny Glover Talks Trouble

Danny Glover is the open-minded actor who has starring roles in The Color Purple and Michel Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind, but who’s also willing to take a bullet in the gut for Saw V. His latest roles have been off camera as executive producer; he’s currently working on a film about Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Trouble the Water, which was released last year and won the Grand Jury Prize for a documentary at Sundance, is up for an Oscar this weekend. The film follows husband and wife Scott and Kimberly Roberts, and includes 15 minutes of their home video, shot on a camera they bought the day before. Upon seeing the raw footage shot for the film, Glover got excited, and he’s still excited. We sat down to talk about the Ninth Ward, and award season.

JA’NELL NEQUEVA: People know you so well as an actor. How is being an Executive Producer different?

DANNY GLOVER: Those titles, Executive Producer or actor, are unimportant. I always try to approach my role as an artist. The first thing you want to do, that you attempt to do as an artist, is to have some sort of input into the material that you are working on. That is how my process begins; I say to myself: “I want to do this kind of work or I want to do that kind of work.”

JN: You also have a production company.

DG: Yes, in partnership with Josyln Barnes; it’s called Louverture Films, named for Toussaint L’Ouverture, who led the Haitian revolution against slavery. Although he’s famous in the Carribean, many people in America still don’t know who he is…

JN: Who brought you into Trouble the Water? How did you first become aware of it?

DG: The film’s two directors, Tia Lessin and Carl Deal, worked on Farenheit 9/11 and Bowling for Columbine. They are both good friends with my producing partner—Josyln Barnes. Tia and Carl gave us some footage from the film. The moment I saw it, I remember sitting in the office, just crying watching it and I said, “I have to get people to see this movie.”

JN: What specifically struck a chord?

DG: My interest is connected to the role I feel that cultural production and art can play in defining the way we look at the world. It’s about redefining images and redefining relationships—and ultimately how we see ourselves.

JN: How does that happen in Trouble the Water?

DG: We watch as the characters relate in their communities—and in a larger context, in the nation and in the world. So the question you ask with an event like Katrina is, “How do you begin to alter that? How we can imaginatively become better human beings?” It’s a kind of idealism essentially, but what would we do this stuff for if we weren’t idealists?

JN: The film primaily follows one couple from New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, before and after Hurricane Katrina. What lessons do you think we learn from this couple’s experience?

DG: The lesson that is important for us to acknowledge, is that what happened in Katrina is symbolic of a much deeper pathology that surrounds poverty with a kind of structural racism and structural disenfranchisement that happens in our cities and in every other city in this country—whether it be through gentrification or some other form of cutting people out or eliminating people as voices. But I don’t even know if lesson learned is even applicable to what we need to talk about.

JN: The film was nominated for an Oscar. Do nominations or awards have any importance for you?

DG: The final outcome of a film is to get people to see it. That’s the test right there. Whether it succeeds in accumulating awards is something that’s based on any number of factors and a lot of those factors you don’t have control over. But certainly the fact is that we got people to see the film and not just to see the film just to sit in an audience—but to see the film and respond in the same way that you did.

JN: The poster for Trouble the Water‘s reads “It’s not about a hurricane. It’s about America.”

DG: It is about America. The symptoms of Katrina are characteristic of a much deeper pathology. If we are only looking at the symptoms and not dealing with the root of that pathology, we miss the point of the film and miss the point of what we need to continue to do. It’s not just about going out there and raising more money for the cause but rather asking how we can effectively establish a place for all people to be a participant in a Democracy.

JN: Do you think that since the election of President Obama that people are in that place? Or most people are in that place?

DG: Well, I don’t know yet. The election was an event—not a movement. It was a huge event that took place over last year, but was the election really a movement? I would think not. Does it have the potential or the possibility to become a movement? Yes.

JN: Lastly, what upcoming projects are you most excited about?

DG: Nothing else.

JN: Nothing else? I don’t believe that!

DG: Believe it.