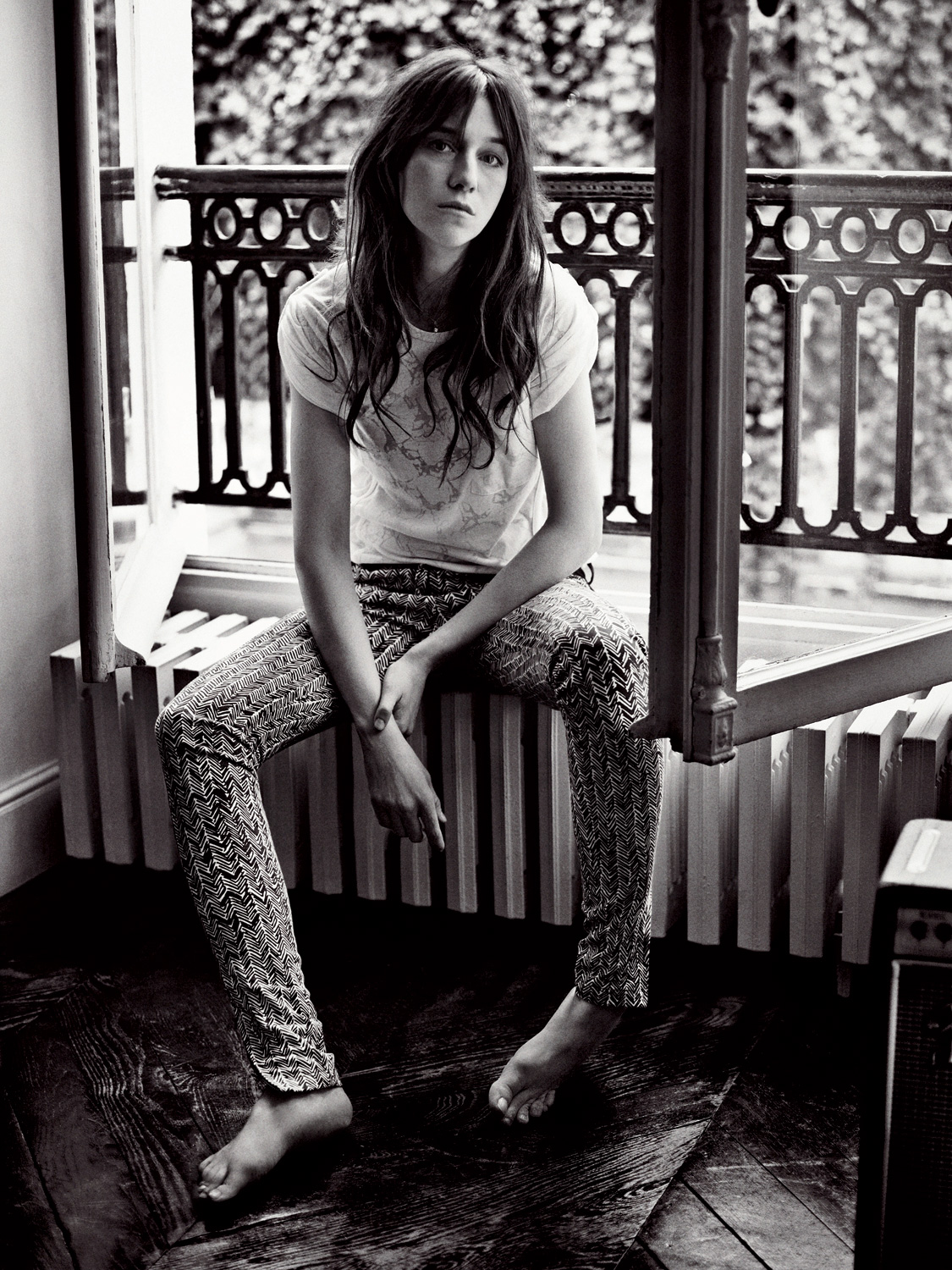

Charlotte Gainsbourg

Charlotte Gainsbourg probably isn’t the kind of person who’d have a résumé. But if she did, it would be impossibly cool. Raised in Paris by überhip pop-star dad Serge Gainsbourg and his muse, the English actress and singer Jane Birkin, Gainsbourg made her musical debut at the age of 13. Her first song, a duet with her father, was called “Lemon Incest,” which, not unexpectedly, caused considerable controversy in France. Gainsbourg completed her debut album at 15, and since then her list of musical collaborators has included Air, Beck, Jarvis Cocker, and Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich. Her new album, Stage Whisper (Elektra), is a double CD, one disc featuring live performances and the other previously unreleased material. It showcases a voice that at times seems to almost hide, never drawing too much attention to itself, but inviting listeners to explore the music’s charming, oddball melodies, which draw on jazz, new wave, cabaret, and electronica. Her songs have a quality of relaxed elegance and unerring good taste.

Likewise, in Gainsbourg’s other career as an actress, she has managed to avoid all of the ego-trappings of movie stardom, instead working with a seriousness and purity that seem to belong to a different era. Onscreen, she can radiate emotions like a filament about to erupt, with a tenderness and honesty that give her work its gravitational pull. Her critically acclaimed films include Michel Gondry’s The Science of Sleep (2006), Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), and Todd Haynes’s Bob Dylan biopic, I’m Not There (2007). In the apocalyptic drama Melancholia, her latest project and second collaboration with Von Trier, Gainsbourg costars with Kirsten Dunst (along with Kiefer Sutherland, Charlotte Rampling, John Hurt, and Alexander Skarsgård) as a highly controlling woman who must confront her helplessness in the face of cataclysmic events. Though she is a master of understatement, as always, her precision, intelligence, and sense of humanity come through loud and clear. Gainsbourg recently spoke with us by phone from France.

DIMITRI EHRLICH: Where are you?

CHARLOTTE GAINSBOURG: Île de Bréhat, an island in Brittany. Can you hear me okay?

EHRLICH: Yes, surprisingly well. I’m in New York City. So let’s talk a little bit about your new film, Melancholia, which I watched yesterday and . . . Wow. First of all, what drew you to this project? It’s not exactly light fare.

GAINSBOURG: Well, Lars von Trier called me last Christmas, and I was so thrilled that he would even ask me because it rarely happens that I get to work again with the same director. I had such a wonderful time on Antichrist that I was going to do whatever he proposed me to do. When he sent me the script, I just loved it. I think I love anything he writes.

EHRLICH: We’ve all heard that Lars von Trier can be . . . How do I put this nicely? Um, difficult. He has been accused of driving his actors to the brink of mental breakdowns. You may be the only person in history to return for a second time as a leading lady in one of his films. Are you a glutton for punishment?

GAINSBOURG: Yes, people thought I was crazy! I think it’s a legend that he’s such a tough person to work with. I really didn’t experience any of that. Of course, he’s difficult in the sense that what he asks for is difficult. For my part in Antichrist, I suffered a bit. But it was the part—it wasn’t him. He wasn’t cruel. On the contrary, he was very kind. You know what you’re up for when you read the pitch.

EHRLICH: I don’t want to give the ending of Melancholia away, but one thought I had watching the film was, What would I do if I could see the end coming? In Buddhism, we have this idea that we should live every moment with awareness: “Think as though at any moment you might be stuck forever with whatever state of mind you indulge yourself in”—the idea being, of course, not to allow hatred and obsession to have too much screen time. Have you thought about that?

GAINSBOURG: I hope I’d have the courage to open my eyes and not close them as my character does.

I’m quite tough—I don’t feel that much pain, and I don’t feel scared about death.Charlotte Gainsbourg

EHRLICH: The movie was inspired by Von Trier’s therapist’s insight that depressives often remain calm in violent situations. Do you relate to that?

GAINSBOURG: Yeah, because they have nothing to lose. When you’re in such a bad state, you’re wishing for the end of the world. So once it comes, there’s no panic. I understand that when you have everything to lose—when you have children—then you go into a panic and it’s unbearable.

EHRLICH: Speaking of family and children, you play a woman who is unable to protect her child. As a mother in real life, what kind of anxieties or bad dreams did that bring you, if any?

GAINSBOURG: This was one of the rare characters I’ve played who I wasn’t proud of, her being such a bourgeois in this house with a husband she doesn’t need to care for. I really couldn’t see any true binding between them. I was ashamed of her reactions—being such a control freak at the beginning and then panicking, being the opposite of a hero, towards the end. But I think I would have done exactly the same. [laughs]

EHRLICH: Do you actually forget who you are when you get into a character? And if so, does that affect who you are when you get home from shooting? Do you have to avoid certain kinds of roles?

GAINSBOURG: It does affect me. I think I am the character when it’s shooting, but then when the day’s over, I don’t think I slip out of that skin. I think you live with that character for the two months of shooting. People around me don’t see another person, but it’s part of my dreams. During 21 Grams (2003), I had terrible nightmares, and I remember on Antichrist, I had terrible nightmares that really had to do with what was going on in the film. So of course you’re bathed in an atmosphere and a character.

EHRLICH: Is your relationship with a director—to Lars or anyone else—like submitting to a cult leader or spiritual master, or do you ever just say, “No, buddy, I disagree with your vision. I’m not doing that”?

GAINSBOURG: Well, I did that with Lars on Antichrist. He asked me if I would be okay taking turns in a sex scene with two shots—in one, instead of Willem Dafoe it was with a porn actor. Lars asked me if it would be okay to be in the same shot with him, and I didn’t see why it would be a problem, so I said okay. And then it went on, and it was just becoming a porn film for me because Willem wasn’t there anymore. I was in a different film, and it was strange. Then he asked me to do another shot, and that’s when I said, “No, I can’t do it.” And he understood very well. He wasn’t pushing me; it was just easier for him to have it all in one shot.

EHRLICH: In your career as an actress, what is the most frightening thing you’ve had to do?

GAINSBOURG: There’s always one moment where you’re scared because you have to dive in—but it can be anything. In Melancholia, the last scene was one of the most difficult things I had to do. We shot it the first time with three actors: Kirsten Dunst, the little boy [Cameron Spurr], and myself. We did the scene, and Lars put on the Wagner music, and it was all going very well, and we did a few takes, and in the end he came to me and said, “I’d like to do another close-up on you tomorrow morning and maybe the next day, just to have different reactions. I don’t know what I want, but you can put yourself in whatever state you need.” And then it was horrible. It’s a bit like filming an animal documentary—you know, when you’re waiting for the moment. I didn’t know what he wanted, what kind of pain he wanted. That was terribly difficult and terrifying because I didn’t know when it was going to stop. I didn’t know when he was going to push me. So we did it two more days in a row, and, yeah, that was a nightmare.

EHRLICH: You’ve worked with some amazing directors: Lars, Michel Gondry, Todd Haynes. What can a director do to pull the best performance out of you?

GAINSBOURG: I think it’s getting me more vulnerable, but it depends on the film. Sometimes you need a bit of confidence. But I think as an actor you’re always vulnerable. You put yourself into somebody’s hands.

EHRLICH: You’ve been acting since you were 13. Your husband [Yvan Attal] is an actor, and your mom is an actor. Great actors are people who can make other people believe they are someone else. On a personal level, how can you really trust a good actor?

GAINSBOURG: [laughs] Because we’re not only liars. Of course we lie very well, but we’re very truthful. Even in a film when I pretend to have an emotion, the emotion is real. Even if I pretend the end of the world is coming, I do believe it when I’m doing it. So it doesn’t mean that there’s a perversion of pretending and that we can’t be trustful.

EHRLICH: I was sitting once with an actress I was involved with and she said, “Watch this,” and she made herself cry. It was so real that it actually made my heart hurt. She just turned on the tears like that.

GAINSBOURG: Sure, but I need sadness to make the tears come. That’s the only way. I can’t laugh if I don’t feel like laughing or cry if I don’t feel like crying.

EHRLICH: You have a new double album, Stage Whisper, which is partly live and partly unreleased material, some of which you created with Beck. Whose voice is it on the song “Got to Let Go”? It sounds like Lou Reed.

GAINSBOURG: No . . . that’s [laughs] . . . Maybe it’s the wind in Brittany that makes me forget everyone’s name. Oh! It’s Charlie Fink [of Noah & the Whale].

EHRLICH: The title of your last studio album, IRM, is French for MRI, and you chose that title because, a few years ago, in 2007, you suffered a brain hemorrhage that could have killed you. Did that brush with mortality affect your outlook on life?

GAINSBOURG: It did affect me very much—in an accidental way. I didn’t have the time to be scared before going into surgery. It happened very quickly, but then when I recovered and I was better and nothing was wrong with me anymore—that’s when I started to be scared and panicked. I just kept thinking about myself all the time. I’m quite tough—I don’t feel that much pain, and I don’t feel scared about death. And suddenly I was becoming this fragile little thing that was scared every minute of dying, of getting a new hemorrhage in my head. That panic continued until Antichrist. It was such a release to be able to work and put my head into something that was stronger than my own little fears and problems. That film was very helpful. I just needed to push everything aside. Thinking about it again for the album was sort of a good memory because I got used to the sound of MRIs, and I wanted to make something with it.

EHRLICH: You also appeared on Madonna’s album Music (2000), which was a great record—and also, I presume, the most commercially successful album you’ve been involved with.

GAINSBOURG: It’s wonderful to be able to do both—to be commercial and have the other side, too. I don’t like being underground or snobbish about commercial projects. I was so proud of being on that album, and I love that song [“What It Feels Like for a Girl”]. It was really surreal when she called me because I couldn’t believe it was really Madonna. I didn’t do anything. She just took my voice from a film [The Cement Garden, 1993] and put it into a song, so I didn’t even meet her. I was very proud. I remember when my father wasn’t having much success, but then when he was writing songs for lovely women, his songs were great hits. He was always longing for success, so I’m not snobbish about commercial things.

EHRLICH: You recorded your first album, Charlotte For Ever (1986), at the age of 15, with your father. What do you remember most about that experience?

GAINSBOURG: What I remember most is the experience before that—my first experience. It was on one of my father’s albums called Love on the Beat (1984), and I was doing a song with him called “Lemon Incest.” I was very innocent, but I knew what the song was talking about. He just asked me to sing, and it was very obvious that I wanted to try, and it seemed to happen in a very natural way. We recorded first in New Jersey. I was 12.

EHRLICH: “Lemon Incest” was a provocative song to sing for a girl who was still just a child—and the daughter of a man with a very public reputation as sexually voracious. Why was that song chosen for you, and what did it mean to you at the time?

GAINSBOURG: My father just wrote it. The meaning is really very explicit in the words, and my father explained it to me. It was a very pure song about the love of a father toward his daughter and a daughter toward her father. The title was provocative, but the actual words that we sang are something very, very innocent. So I understood it that way. I love my father very, very much, and he loves me, and we just said so in the song. I didn’t even notice that there was a scandal afterward because I was in a boarding school in Switzerland, so nobody was aware of that. I mean, it didn’t harm me. And now when I listen to it, I do love the song because I can hear my voice being so young and his voice. It’s very special. When I did my own album—when he wrote more songs for me—it was different. I was happy to do that with him because he was like a conductor when you sang with him—like a director. He wanted things very specific. He liked mistakes; he didn’t want you to sing too well. He wanted the . . . how do you say it?

EHRLICH: Fragility?

GAINSBOURG: Yeah. He didn’t want tough voices. I just remember that pleasure of seeing him happy. But it was very much his words, his ideas, his music. Then when I was able to do my own album without him, I realized I had things to say. Even if I didn’t write the lyrics, I had subjects that were my own. And then when I wanted to do live shows, I went back to see if I could sing any of those songs I sang with my dad again. But it’s impossible because the words are really the words of a father. It’s not a portrait of myself, so I couldn’t sing any of those, even if I do like them.

EHRLICH: Why did you wait 20 years before you made a second album? That’s a long time between records.

GAINSBOURG: It’s a very long time. I lost my father when I was 19, and it took me a very, very long time to . . . Not overcome his death, because I’ll never overcome it, but I thought I would only be able to work with him—next to him, with his words. That’s what I liked. So I thought I would have no pleasure doing it on my own, or even with somebody else. I think the fact that Madonna used my voice on one of her songs changed that a little bit because it was as if I was becoming independent from my father, just a little bit. Then Étienne Daho asked me to do a duet with him, which I did, and, again, I was being a little more independent. And then I met Air, and things became possible after a year of discussion. I was really scared to push myself, and after a while they said, “Look, we can’t just discuss an album. We have to get into the studio and try things out, and if you don’t like it, we can stop. But we can’t just talk about it.” So they pushed me, and it was a good thing.

EHRLICH: Growing up in Paris with celebrity parents must have created some problems for you—and obviously opened up a lot of doors.

GAINSBOURG: To me, they were really just my parents. We had a lovely life. We went to private school. But they had quite an eccentric life, going into nightclubs and coming back when we got up to go to school. That was kind of weird. But apart from that, we had a very normal life. They had simple tastes. Their idea was to always keep your feet on the ground, so that’s what we did. I was able to go on the street, and it was normal when people came up to them and asked for autographs. It was just part of everyday life. I just learned through their way of living—through all of that fame to always be happy when someone comes up to ask for an autograph. People really loved them in a very honest way. It wasn’t until very late that I understood what my father was writing about. I had lived with his songs all my life, but I never really understood the lyrics, or what went into them. Of course, it is special because now I know that my father was a genius. But he lived in a very casual way.

EHRLICH: Last question: You strike me as a little bit shy. If that’s true, why do you spend your life in public, making movies and music?

GAINSBOURG: I think that’s the real contradiction of being an actress. A lot of actors are shy. With music, I had to push myself to do live shows because it was really the opposite of who I was. Still, I got such a kick out of it. I think that’s what I love the most: when I have the impression that I have a limit and that I’m pushing myself a little bit. Not in a dramatic way—I don’t think of myself as being a rock star. I did a show in the U.K. at a festival, and then a day later I was in Sweden to shoot Melancholia, and the difference was so huge—to have a crowd of people screaming your name to then being completely quiet. You have to push your ego down. It was very funny to have those feelings so close to one another.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a writer, producer, and songwriter.