Brian Cox

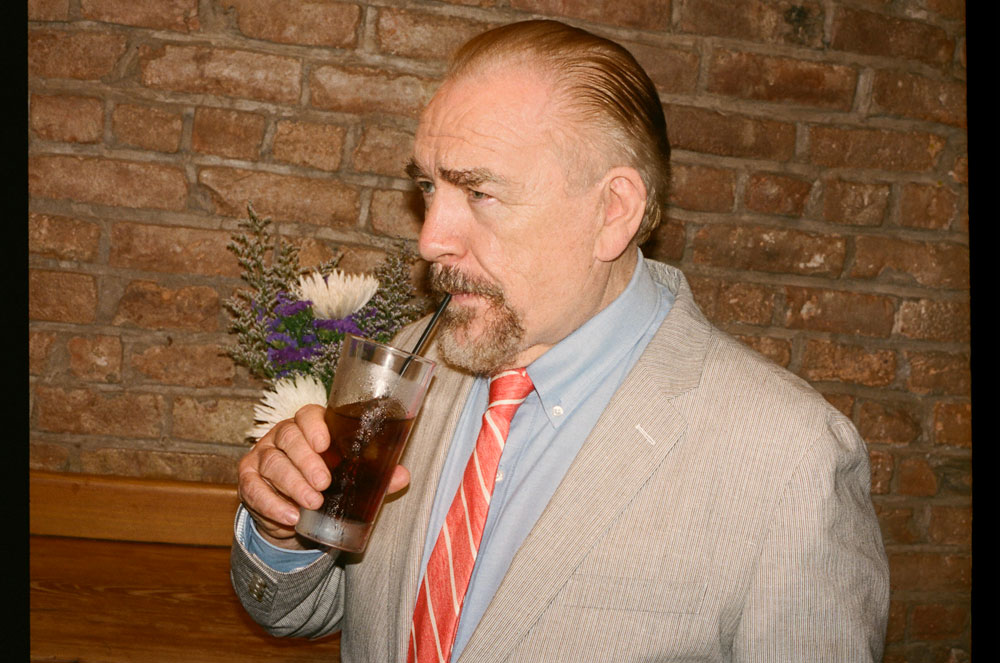

BRIAN COX AT MOTHER’S RUIN IN NEW YORK CITY, MAY 2017. PHOTOS: ROBERT NETHERY. STYLING: MARINA MUÑOZ/LALALAND ARTISTS. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ FOR HONEY ARTISTS USING TOUCHÉ ECLAT.

Brian Cox is a hardworking man. For the last two and half decades, the Dundee, Scotland native has acted in multiple films every year: from Oscar winners (Braveheart, Adaptation, Her) to big-budget blockbusters (The Bourne Identity, The Bourne Supremacy, Troy, X-Men 2) to cult favorites (Rushmore, Supertroopers). After training at LAMDA in the 1960s, he began his career in the theater. By the time he began focusing on film and television, he’d acted opposite Laurence Olivier in King Lear at the National Theatre in London and won an Olivier Award for his starring turn in Titus Andronicus with the Royal Shakespeare Company. Among the directors he’s worked with are Woody Allen, Noel Clarke, Wes Craven, David Fincher, Spike Jonze, Spike Lee, Ken Loach, and Michael Mann. The real-life figures he’s played include Trotsky, Marlon Brando, and, in his latest film, Churchill, out tomorrow, Britain’s most famous Prime Minister. It is a career-crowning role for the 71-year-old.

Here, Cox talks to his good friend, and another former director, Hampton Fancher. After a career as a dancer and actor, Fancher famously wrote the screenplay for Blade Runner in 1982, and will return this autumn after an 18-year hiatus with Blade Runner 2049. He is the subject of Michael Almereyda’s soon-to-be-released documentary Escapes, and his colorful questions for Cox were in part inspired by Max Frisch’s posthumous questionnaire, which Almereyda once shared with him.

HAMPTON FANCHER: This is going to be a tennis game, a ping-pong game. When did you stop believing you could become wiser, or do you still believe it?

BRIAN COX: I still believe it.

FANCHER: [laughs] Are you convinced by your own self-criticism?

COX: Yes.

FANCHER: That’s so sweet. Can you recall being proud of yourself for a specific action?

COX: Yes. Some of things I stood up for. My stand on Scottish independence.

FANCHER: Do you think authenticity is always in flux?

COX: Yes, to a certain extent. There are some people who maintain it. You maintain your authenticity.

FANCHER: What do you have most in common with Churchill?

COX: I’m child-like. The qualities of a child. Loneliness. Exasperation. Frustration.

FANCHER: What was the most challenging, or the hardest part, of the stretch you had to make to play Churchill?

COX: Tying the ends together—tying the public self and private self together. That was the big challenge of the role.

FANCHER: You did that really well. When I woke up this morning and thought about what I’d seen you do [in Churchill], I realized—and it’s a silly analogy and it’s made a lot, but it really made sense to me—”Fuck, Brian’s basically a lion. He’s an old, scruffy lion.” That could be applied to Churchill as well. Would you like to be free of secrets?

COX: Oh, yeah. I am pretty free of secrets. I can’t keep a secret; I’m hopeless.

FANCHER: Can you remember, precisely, being a coward?

COX: I can remember precisely being a coward. This is a bit of a long story…

FANCHER: You’ve got to make it fast, man. We’ve got a lot of ground to cover.

COX: Somebody rang me up once about if I could help them with their green card—if I could write a letter for them. It was somebody that I was not particularly enamored by. I said, “Oh sure.” I wanted to be okay, Mr. Nice Guy, which was actually an act of cowardice on my part. And my girlfriend at the time said, “You bloody hypocrite. After all you’ve said about that person, how can you be nice? I can’t believe you!” I didn’t want to offend them—I was a bit afraid to offend them. [But] I rang the person back and said, “I’m sorry, I can’t back you up in your green card.”

FANCHER: Well, you came through.

COX: I did, but I did have a moment of cowardice.

FANCHER: What’s your own favorite death?

COX: I suppose in my sleep.

FANCHER: What traits do your former lovers have in common?

COX: Tremendous sexuality.

FANCHER: They’re passionate people.

COX: Very passionate. And innate wisdom.

FANCHER: In a farting contest, who’d you put your money on: Timothy Hutton, Brad Pitt, or Clark Gable?

COX: I think Clark Gable.

FANCHER: What’s the best thing about you?

COX: Loyalty.

FANCHER: Do you feel sorry for Anthony Weiner?

COX: Can you remind me who Anthony Weiner is again?

FANCHER: He’s the politician who’s been caught in serial events of texting girls sexually who are underage. He’s been in the front page lately a lot for just doing it again. He can’t stop.

COX: Well, he needs help. Of course I feel sorry for him.

FANCHER: What’s the hardest part of doing what you love to do?

COX: The cost to family.

FANCHER: Does a box of fat, dead wire intrigue you?

COX: No.

FANCHER: In 1959, a Muscovite tasted Pepsi for the first time. How does that make you feel?

COX: I don’t feel anything.

FANCHER: “They both married smart, cute, little Jewish guys with high voices.” Does that sound mean or sweet?

COX: Misguided.

FANCHER: What painter paints like you think or closest to it?

COX: Modigliani.

FANCHER: Interesting. Sexual again. Would you, if you could, want to hear what your friends say about you when you’re not there?

COX: I’m intrigued.

FANCHER: Do you have a particular grief that can always be counted on to show up again?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: Have you truly tried to rid yourself of it, or has it become an old friend?

COX: It’s just there. It hovers over me.

FANCHER: A familiar. Would you be less lonely without it?

COX: I’d be a lot less lonely without it.

FANCHER: Do you think adult loneliness is a form of narcissism?

COX: No.

FANCHER: Which best suits your soul: facedown, nose in the grass, or on your back looking at the sky?

COX: Looking at the sky.

FANCHER: What do you find more fulfilling: vicarious revenge or the real thing?

COX: Vicarious revenge.

FANCHER: Do you think yourself successful in staying clear of things you can’t accept?

COX: Not wholly.

FANCHER: What must you learn?

COX: Truth!

FANCHER: Did you have an abiding fantasy as a child?

COX: To be in movies.

FANCHER: Wow, beautiful. What is it that makes you sure someone is your good friend?

COX: Persistence in their own life or persistence in our friendship. I admire people who don’t give up, because I can be a little flaky. And they’re stronger than me.

FANCHER: Would you change your name—I’ve got to think in your case, because you have some money—for a billion dollars?

COX: Probably.

FANCHER: Would you change your name to Gordon Cockwater?

COX: No. Forget it. I wouldn’t change my name if it was Gordon Cockwater.

FANCHER: Not for a billion?

COX: Not for a billion, no. When I’m faced with that proposition, no.

FANCHER: Dead, unfound in the desert, would you prefer to be eaten by coyotes or vultures?

COX: Vultures.

FANCHER: When was the last time you hid in the bushes?

COX: Whenever I have a party. Whenever I’m entertaining a big group of people, I sometimes go and hide in the bushes.

FANCHER: Ten minutes of Glenn Gould improvising with Thelonious Monk, or Mark Twain talking with Oscar Wilde?

COX: That’s a hard one.

FANCHER: Think about it for a moment. You can’t lose.

COX: I’d have to go for Mark Twain talking to Oscar Wilde.

FANCHER: What do Hitler, Kafka, and Miles Davis have in common?

COX: No idea.

FANCHER: They’re all vegetarians. Would you rather have dinner with Whitman or Poe?

COX: Whitman.

FANCHER: Who’s the most irritating writer that you love?

COX: Charles Dickens.

FANCHER: Wonderful. Fuck me. Would you rather make a fool of yourself for money or love?

COX: Money.

FANCHER: [laughs] What’s the assumption if a sailor’s coat is found in a dingo’s den?

COX: This poor sailor wandered way off course and ended up eaten by this dingo. He went into the den to get some protection, and there was the dingo and it ate him.

FANCHER: He was looking for shelter and he got destroyed. Why do you hide your pain, if you do?

COX: Because it’s too much sometimes. And it’s a bit selfish, my pain.

FANCHER: Have you lied to a friend for personal gain?

COX: Never.

FANCHER: Is extinction inevitable?

COX: I think so.

FANCHER: Do you believe extinction is replaced by improvement?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: What three creatures would you like most not to be?

COX: I don’t think I’d like to be a mosquito. I don’t think I’d like to be a worm. I don’t think I’d like to be a jellyfish.

FANCHER: What’s one of the most important things you’ve failed to do?

COX: Reconcile myself with elements of my past.

FANCHER: Have you ever thought of having sex with a little person?

COX: Never.

FANCHER: What’s the opposite of invention?

COX: Subvention. Money for nothing.

FANCHER: Can you disprove Hegel’s idea that history is the story of liberty becoming conscious of itself?

COX: No, I would go along with Hegel.

FANCHER: If you were a woman, would you rather make love with Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster, or Robert Mitchum?

COX: Robert Mitchum.

FANCHER: What about Robert Mitchum or Gary Cooper?

COX: Possibly Gary Cooper, but I think still Robert Mitchum.

FANCHER: Okay. As it is: Louise Brooks in her day, Kate Winslet, or Barbara Stanwyck?

COX: Stanwyck. I’m tempted by Louise Brooks, but I think ultimately Stanwyck. Certainly not Kate Winslet. No way.

FANCHER: What if we throw Cate Blanchett in there?

COX: Oh, no, no. Definitely not. That makes my choice even easier.

FANCHER: Do you believe mustard is smarter than ketchup?

COX: Yup.

FANCHER: Why?

COX: Because it has more zing to it.

FANCHER: If a head of cabbage is dumb, how come sauerkraut is not? Or is it?

COX: No, it’s not. It’s good. It’s done by the Germans. It’s a very hard thing to do unless it’s a real Kraut. Only Krauts eat ‘kraut.

FANCHER: Shall good tell bad what not to say?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: You’re a man of the rules. Does the attainment of political liberty necessitate governing personal freedom?

COX: I’m afraid so.

FANCHER: Mmm-hmm. Scotsman.

COX: I think it’s inevitable. I don’t think there’s anyway you can avoid that. We have too much personal freedom as it is.

FANCHER: Do you think that sometimes you unwittingly cooperate with the forces that defeat you?

COX: All the fucking time. [laughs]

FANCHER: Do you think those forces reside within you as opposed to outside of you?

COX: They’re within me.

FANCHER: Which of the seven deadly sins might apply: pride, envy, wrath, sloth, covetousness, gluttony, lust?

COX: Sloth with a hint of covetousness.

FANCHER: Do you believe in big picture progress or think that worse is neck-in-neck with better?

COX: I believe in progress, but I don’t think it happens. I’m an optimist.

FANCHER: You’re in good faith, generally. Can seeing ourselves as ridiculous teach us out of complaint?

COX: Yes. Absolutely.

FANCHER: Do you pretend to be valiant?

COX: Yes.

FANCHER: When you feel divided, destabilized, are you afraid to make known your instability?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: When you tie your shoe, do you sometimes see your cremated leg burning like a log?

COX: Never. But I will from now on. [both laugh]

FANCHER: Have you spoken to a corpse?

COX: No, I haven’t.

FANCHER: After the toilet paper is gone, is there a little piece of you tempted to save the cylinder?

COX: Yes, there is.

FANCHER: What would you rather have, a Hans Holbein or an Albrecht Dürer?

COX: A Dürer.

FANCHER: Do you want to be seen as you see yourself?

COX: I would occasionally like that.

FANCHER: Did you ever come close to ruining anyone’s life?

COX: Yes, I have. It was a young woman with too much expectation and I didn’t honor her.

FANCHER: Can you usually improve in what you don’t approve of?

COX: Yes.

FANCHER: What would you name Frankenstein’s yacht? As in the monster, not doctor.

COX: My going places vehicle.

FANCHER: What are the consequences of no room for exception?

COX: A narrow life.

FANCHER: Do you find it fun to decipher, unscramble, make the unintelligible intelligible?

COX: Yes, I love it. My favorite pastime.

FANCHER: Are you satisfied with your accomplishments?

COX: On the whole, yes.

FANCHER: What do you think about a dildo in a bedpan?

COX: They both have uses and one mustn’t be fearful of them.

FANCHER: Either two hours in the summer of 1601 at dusk in Venice shopping along the Rialto, or safe and sound having dinner in one of the better restaurants in New York, 100 years from now, including a 15 minute walk around the block?

COX: No, no. Venice, 1601.

FANCHER: Do you think sometimes Putin might know he’s a thug?

COX: I think Putin does know he’s a thug, but he doesn’t give a fuck.

FANCHER: What do you think Bugs Bunny smells like?

COX: Fresh. Carrot-y.

FANCHER: Does tomorrow feel closer than yesterday?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: Is it easier to put it on or take it off?

COX: It’s easier to put it on.

FANCHER: What, if anything, have you acquired in distant regions?

COX: Enormous knowledge. A sense of that which is not complacent.

FANCHER: You’re a real philosopher. Is hell the devil’s utopia or is he a prisoner?

COX: He’s definitely a prisoner.

FANCHER: If your soul had a voice, what would it sound like?

COX: Sweet. Melodious.

FANCHER: Do you have any idea what it might say?

COX: It would just say, “la-la-la-la-la, la-la.”

FANCHER: As a child, did you have a relationship to either your mother or your father’s clothes?

COX: Yes. My mother’s stockings and my father’s wardrobe after he died—all his new clothes, his new trousers stay with me. Whenever I buy new clothes I still remember my mother saying, “What will we do with all your father’s clothes we just bought?”

FANCHER: Do you believe there is a mind?

COX: That’s questionable.

FANCHER: If there is a mind, what does it do?

COX: Confuses you.

FANCHER: So you don’t think that you are your mind?

COX: No, I think I’m only an element of that. Your mind has many mansions to it: there’s the mind that sells you a false bill of goods, there’s the mind that gets distracted, and there’s a little bit of the mind which is the “I am” element. Sometimes they’re all fighting one another.

FANCHER: We use the word “soul” to mean something, do you believe in the meaning of it?

COX: I believe in the meaning of it.

FANCHER: Do you know what it does?

COX: I equate soul with consciousness.

FANCHER: With your heart of hearts, would you rather be acknowledged for being good, as in goodness, or great, as in renowned?

COX: No, good as in goodness.

FANCHER: What is the heuristic significance, if any, of a fashion magazine in a butcher’s shop?

COX: There’s more to the butcher than meets the eye.

FANCHER: Occasionally Wagner had breakfast on purpose near his chickens. Is that true or false?

COX: Wagner, probably true.

FANCHER: Are you willing to open the new one before the old one is empty?

COX: I have to stop myself from doing that, but I have an instinct to open the new one.

FANCHER: Do you sometimes feel disappointed that a better class of people are not your best friends?

COX: Yes.

FANCHER: [laughs] Have you been in love with a poor loser?

COX: Yes.

FANCHER: Do you believe you know more truth than you have the ability to express?

COX: Yes. It’s probably arrogant, but yes.

FANCHER: Do you think life is less absurd because it is absurd?

COX: It’s absurd. It would be absurd to think it wasn’t absurd.

FANCHER: Are there things you don’t want to know?

COX: There were. I’m not sure that applies anymore.

FANCHER: In the pocket of a bald man’s coat, what sounds best, a hairpin or a comb?

COX: A comb.

FANCHER: Why is it that we love the past so much—our own as well as the rest?

COX: It’s history, and we love history because history is the one means of making sense of our lives as of now, that can contribute to making sense of our lives.

FANCHER: Did you receive any physical punishment from your parents as a child?

COX: Never.

FANCHER: Which would you rather have: a symphoniously pastoral Gainsborough, or a harmoniously tropical Gaughin?

COX: Probably the Gaughin.

FANCHER: There’s your sex again. Do you think Primo Levi committed suicide or was it an accident on those stairs?

COX: It’s such a strange way to kill yourself. Hanging yourself is one thing. I think it might’ve been an accident.

FANCHER: Who is it that knows your fear and your courage?

COX: I think my wife does.

FANCHER: What do Dave Brubeck and Arthur Miller have in common?

COX: I don’t know, but they’re both great jazz players. Or Miller’s a jazz writer, and Brubeck’s a great jazz player. What did they have in common?

FANCHER: They look so much alike. Do you take your toilet for granted? Are you ever concerned it might not flush?

COX: Oh yes, always.

FANCHER: Do people like you?

COX: Some people like me and some people don’t.

FANCHER: Why do you think good, descriptive prose can sometimes give such a jolt of joy you almost weep?

COX: Because of the capacity of the human to embrace words in such a way—it gives you hope for humanity.

FANCHER: Are satyrs—the goat-footed sex-maniacs—carnivorous or herbivorous?

COX: I think they’re herbivores.

FANCHER: Do you ever catch yourself desiring to be envied?

COX: Yes, I would say that that could be a sin of mine.

FANCHER: Do you think there’s no absolute truth as an absolute?

COX: I would’ve said so.

FANCHER: What, if anything, gives you a touch of pride about the circumstances of your upbringing?

COX: The longevity of my sisters.

FANCHER: Was there a political influence conveyed to you as a child by family members?

COX: Yes, absolutely.

FANCHER: Who was the largest ethical guide in your life as a child?

COX: My father.

FANCHER: Do you find the thought that you might never have been born disturbing?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: When you think of somebody now dead, would you like them to speak to you, or would you rather say something more to him or her?

COX: I’d like them to speak to me.

FANCHER: Do you love anybody?

COX: Oh yeah.

FANCHER: How do you know?

COX: I just know by the feeling.

FANCHER: What do you need in order to be happy?

COX: I need contentment. I need to feel that my world is safe. I need to feel safe.

FANCHER: How do you define masculine?

COX: Masculine is one part of a balancing act, and if you get it right, it’s good, but a lot of people don’t get it right. A lot of people fall into traps. It’s a very evocative word, and it’s not necessarily a word that gives you the right idea.

FANCHER: Would you care to be your own wife?

COX: Yeah! No, what am I saying? I’d hate it.

FANCHER: [laughs] Can hate breed hope?

COX: On occasion.

FANCHER: What fills you with hope: nature, art, science, or the history of mankind?

COX: Nature.

FANCHER: Do you hope for an afterlife?

COX: Yeah, part of me does, but I’m running out of that bit. I used to hope a lot more than I do.

FANCHER: Have you enemies with whom you would secretly like to make friends so you can admire them with less difficulty?

COX: Absolutely.

FANCHER: Are you friends with yourself?

COX: Yes, I am, actually. I am friendly with myself.

FANCHER: Do you like fenced enclosures?

COX: It depends on the freedom of the space around.

FANCHER: Would you like to know what it feels like to die?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: Do you ever think, “Serve you right if I died!”?

COX: Yeah.

FANCHER: Do you know where you’d like to be buried?

COX: I don’t, and it’s a great question for me. I’ve been considering it. I don’t even know if I want to be cremated. I think that’s not my problem—that’s somebody else’s problem.

CHURCHILL COMES OUT IN SELECT THEATERS TOMORROW, JUNE 2, 2017. HAMPTON FANCHER IS A NEW YORK-BASED WRITER AND FILMMAKER. HIS PAST WORK INCLUDES THE SHORT STORY COLLECTION THE SHAPE OF THE FINAL DOG AND OTHER STORIES (BLUERIDER, 2012); THE 1999 FILM THE MINUS MAN, WHICH HE WROTE AND DIRECTED; AND THE SCREENPLAYS FOR BLADE RUNNER (1982) AND THE MIGHTY QUINN (1989). HE IS THE SUBJECT OF THE DOCUMENTARY ESCAPES, OUT NEXT MONTH, AND HIS NEXT FILM AS A SCREENWRITER, BLADE RUNNER 2049, IS DUE OUT IN OCTOBER.