A Girl and Her Super Pig

If anything is going to make you think twice about eating bacon, it is writer-director Bong Joon-ho’s latest film, Okja. Out today via Netflix, Okja revolves around the strong familial bond between a young Korean teenager named Mija and her unusual pet: the large, docile Okja. Loaned to Mija’s grandfather by an unscrupulous American agriculture company, the Mirando Corporation, Okja is described as a “super pig,” but looks more like a hippopotamus with the gentle face of a manatee. She is fiercely loyal to Mija, for whom she is pet, companion, and family. “Okja was always female,” explains director Bong via a translator. “I wanted to play with the sister-like relationship between Okja and Mija, two little girls.”

Bong first envisioned Okja seven years ago while writing the script for his last film, and his first English language project, Snowpiercer (2013). “I was driving in the city of Seoul, and I imagined this big animal in the streets. It was so big in size, but had such a sad face,” he tells us. “This gave rise to a bunch of questions, which expanded the story: Why does she have such a sad face? Who is her family? That let to the creation of the protagonist, Mija. The question of Okja’s size led to the inception of this big food industry that was behind the creation of this animal.”

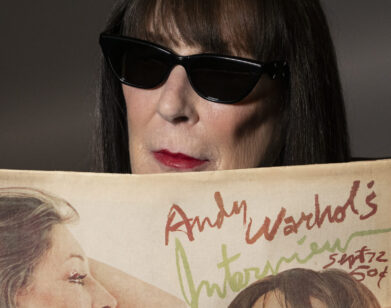

Though Mija is played by a relative newcomer, Ahn Seo-Hyun, there are plenty of familiar faces in Okja. Tilda Swinton, who also starred in Snowpiercer and is one of Okja‘s producers, serves as two of the film’s main antagonists: the slightly pathetic current CEO of the Mirando Company, Lucy Mirando, and her former CEO sister, Nancy. “Tilda contributed a lot creatively to the film,” says Bong. “I had such a great time working with her on Snowpiercer, based on that experience, I trusted Tilda to do the same for Okja.”

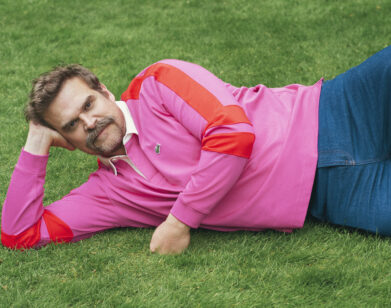

Alongside Swinton on team Mirando are Jake Gyllenhaal, as a shrill, washed-up television vet, and Giancarlo Esposito as Lucy’s right-hand man. Paul Dano, Lily Collins, and The Walking Dead‘s Steven Yeun co-star as members of the real-life animal rights organization ALF, determined to save Okja from Mirando, and call public attention to the conditions in Mirando’s slaughterhouses.

“My purpose was never to make a propaganda film,” Bong emphasizes. “I never wanted to convert the audience to veganism, or scold them for not becoming vegans after watching the film,” he continues. “In the grand scheme of nature, I believe that it is very natural that animals eat animals, and that humans eat animals. It is only in the last couple of decades that meat-processing factories have come to rise, and I believe we should take time to reflect on that reality.”

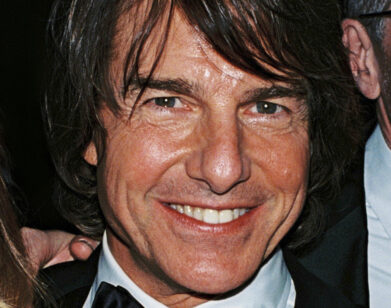

For the English dialogue in the film, director Bong collaborated with screenwriter (Frank, 2014; The Men Who Stare at Goats, 2009) and journalist Jon Ronson. “I watched Frank and was really impressed with it,” Bong remarks. “I loved the humor, and there was a certain sadness to the humor as well.”

EMMA BROWN: How did you first get involved in the film? I know that, with some of the other cast members, director Bong first approached people with an image of Okja. Is that what happened to you?

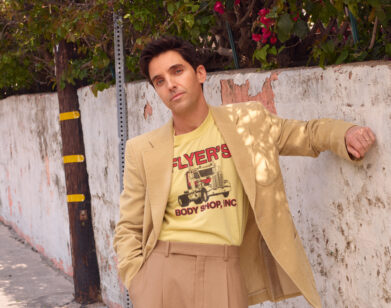

STEVEN YEUN: I actually got to meet director Bong two years prior to the film in Korea just by some happenstance. We had a coffee and chatted, and I told him how much of a fan I was. I’m thankful that he didn’t find me super strange. But then I got an email about a year later and he said, “Hey, I’m writing this role with you in mind.” I freaked out. To me, director Bong is one of the greatest directors, so it was just an honor and a privilege. I would have gladly said yes to anything and everything that he wanted me to be in.

BROWN: Did you know you’d definitely be able to commit to the film? I know that The Walking Dead monopolized most of your time.

YEUN: I was going to try my hardest, regardless of anything, to do it. We actually ran into some potentially rough scheduling issues, but what was really cool was that director Bong has a pretty solid vision of what he wants. He doesn’t ask an actor to play a character just because they can do the lines; he really has a keen eye to cast specifically for a role based on what he feels like the actor might exude. They very much advocated for me to be a part of the film and we got to work out a lot of the bumps so I could be a part of this film, which I am so grateful for.

BROWN: I was watching some of your interviews from Cannes, and you were talking about how your character K is both the bridge between two cultures—Korean and Western—and also his own island.

YEUN: I think director Bong knows the unique specifics of what it might be like to be an immigrant Asian-American, and to that end, what it’s like to be Korean-American and come to Korea. We didn’t talk specifically about it. Director Bong is a native Korean; some of the issues that happen to be normal for Asian-Americans aren’t the same things that he goes through. The brilliance that he has is the ability to absolve himself of knowing that nuance and instead get someone specifically to fulfill that. As I was doing it, it just reaffirmed, even in the way that he wrote it, the same thoughts that I have all the time. K is his own island; the country that he truly identifies with doesn’t think that he is part of it, and the country that he is supposed to be a part of doesn’t understand who he is. That was a really surreal experience.

BROWN: K translates between Mijo and ALF during the film, and when I first saw it, I wasn’t sure if he was just being lazy in his translations, or if he lacked the language ability to translate what Paul Dano was saying.

YEUN: Yes, that is quintessentially the position that K finds himself in. If his Korean were spectacular, if it was completely perfect, then he would have a place to identify with and people would understand him. But truthfully, the more common experience is to not have that ability; there are certain cultural differences that won’t allow you to know the nuance of a language the way that you think you should. It’s going to be different for a Korean audience. A Korean audience is going to know that, every single time, what K is translating is actually a really shitty version of what Paul has said. But those are the interesting things about this film—you can watch it from any vantage point, and it’s going to be very different for whoever sees it.

BROWN: How much did director Bong tell you about K’s backstory and how much did you invent?

YEUN: The process was very collaborative. I would throw him some ideas here and there, and he might jump on one and then expound on it, or he might say “What if it was like this?” He would regularly come and drop little nuggets of gold on me, like, “K probably sneaks burgers and he justifies it as a means of keeping his strength up for the mission.” For me, the gaps that I filled in were more motivations: Why does he continue on this mission? Why does he try to redeem himself? Why does he get that stupid tattoo? You realize that K really wants to belong to something and people won’t let him.

BROWN: I suppose because Okja is a fictional creature, I wasn’t expecting to be so affected by what she goes through and how that relates to the production of the meat we consume.

YEUN: I think that’s the beauty of this film: It looks like it’s going to be this fantastic adventure movie with this little girl and her giant pig best friend, but as director Bong weaves you through this adventure, you realize that it’s not that surreal, or crazy, or fantastical. It’s actually very real. He doesn’t try to give you some sort of an agenda and tell you whether you should or shouldn’t eat meat; he just shows you the reality of the situation. He didn’t embellish the slaughterhouse—he went to a physical slaughterhouse to research the film. If anything, the way that you feel is a direct indicator of how far we’ve come from our symbiotic relationship with nature. In that way, when someone hangs a mirror to every single blemish that’s on us, it makes you really reassess what your morals are.

OKJA COMES OUT TODAY, JUNE 28, 2017, VIA NETFLIX.