The Disappearing Act of Benedetta Barzini

Courtesy of Kino Lorber.

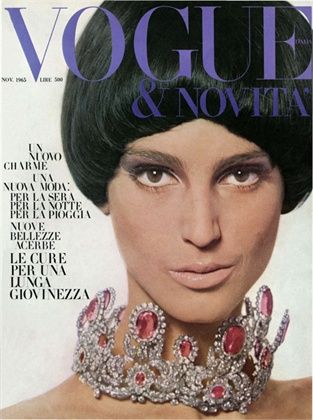

Benedetta Barzini—Marxist feminist, the first Italian model to land a cover of American Vogue, and a friend and muse of the likes of Salvador Dalí and Richard Avedon—is now 76 years old. With time, she has come to fiercely disavow the fashion industry and despise images. The Disappearance of My Mother, which, after a run in New York and LA is currently playing in select cities and streaming soon, is an attempt by Barzini’s son, the filmmaker Beniamino Barrese, to pin down his mother’s many multitudes. The film begins as an ode to an icon and becomes a confrontation, a search, a searing struggle between mother and son to clarify how they see each other and the world around them. Barzini spoke with Interview—however bluntly—about truth, gender, and the difficulty of disappearing.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: I know that the process of creating this film with your son was certainly a complicated one for you. How do you feel about the film as a completed thing?

BENEDETTA BARZINI: I can’t be objective about the film or give a judgement on Ben’s work. I can say that one of the reasons why I dislike—hate—images is that they are the least interesting thing about what they try to illustrate. When I see sequences, I see Ben hovering around with all his equipment, trying to find where to place the camera and the energy he put into his work…the objects in my small environment were pushed around, and this made me feel invaded. Having been obliged to say yes has made me feel again and again how often women say ‘yes’ when they want to say ’no’ and how this has occurred for centuries. In the end, all the successes that Ben has had makes me very proud of him and hopeful for his future. So, if I could give him a hand to express his idea, so much the better…

WILLIAMS: Ben gets right up on your wrinkles, your grey hairs, those things you’ve said the fashion magazines would rather ignore. Why do you think society is so afraid of making age visible?

BARZINI: Men’s age can be visible. The older they get, the more their prestige grows. Old men are considered wise. Old women are simply ugly old ladies. Gods don’t get old. Zeus was born old, same as the god of the one-god-cultures. Apollo stays young forever. Venus too. Fighting age is part of the struggle to control nature. For women, getting old means losing their looks, and since they have little to nothing to say, it means they lose their seductiveness (read: the possibility to be “loved”). Fashion magazines simply follow the conservative idea that women’s main activity is to turn themselves into pretty geishas for the pleasure of men. This, in the evening, after having perhaps been some sort of CEO somewhere. It will take a long, long time for women in the world to have the necessary awareness so as to get rid of the idea of being the second sex born out of a man’s rib. But people love fairy tales, and fashion magazines only depict unreal-looking people.

WILLIAMS: When you were in New York, you spent some time with Warhol. Do you have any memories of him?

BARZINI: I never spent time with Andy, I spent time with the people that were spending time with Andy. I remember Max’s Kansas City … chickpeas and beer. I remember watching them get drunk but also getting drugged. I never participated in the becoming a part of Andy’s surroundings. I was like somebody on the windowsill watching what was happening below. I thought Andy was ferocious. And very vindictive. He despised all these sons and daughters of very wealthy New York people that were buying his things. And he enjoyed seeing them grasp—and have nothing to do in life, and have no idea who they were. Edie Sedgwick is just one example. He loved that. He thought it was fantastic to see them, like cockroaches, just crawling around with nothing to do except trying to please him. It was interesting. Very interesting.

WILLIAMS: I read this conversation that you had with your niece about a year ago where you were talking about New York and you kind of described being disillusioned with the city. Has that gotten worse?

BARZINI: Well, I don’t like New York at all. When I got there recently, because of the film, the only thing I could do was stay in bed all day because I was very sick and just trying to pull myself together for the Q&As. I cannot stand that city. I just despise it. It’s something that has to do with the tremendous effort that I made to be a model—running around New York with my book, and people are looking at you like you’re a piece of machinery, saying “Let me see your profile!” Things like that. In those days, I never really thought about it. I had to do it and I did it. But now I resent the city, I resent the skyscrapers…6th Avenue has nothing to do with what I remember. You can keep your New York, I don’t want it.

Benedetta on the cover of a 1963 edition of Vogue Italia.

WILLIAMS: Well, it does seem like the buildings are getting taller and taller, and shinier and shinier…

BARZINI: Just awful. You can keep it.

WILLIAMS: I’m curious about your thoughts about the push toward making clothing more gender-neutral or universally accessible.

BARZINI: That’s a bit of a big question, but I’ll give you a partial answer. My feeling is, I don’t understand why women have a hundred thousand ways of dressing and men only one. Okay. So that’s where I go. They’re just like, oh, I don’t know, clay. You can put anything you want on them, and they’ll follow suit. And if you tell them it’s fashionable, that’s fine, they’ll wear it. So by the way women behave, in terms of consumption, my feeling is they have a long way to go. And on the opposite end, no designer could take a jacket off a man, and say from now on, they’re going to wear a robe. Whereas any designer can tell women what to do, no designer can tell men what to do. Do you see what I mean? I think it should be reconsidered.

WILLIAMS: Do you think any ethical fashion industry can exist in the future?

BARZINI: No. I think it’ll take something like two hundred years. Well, we won’t see it. It takes time to change things. What the hell, it’s not something that’ll happen in a few generations. Sooner or later, women will stop being considered the aim of all marketing.

WILLIAMS: What do you think the aim would be?

BARZINI: If you’re aware, you know what to do with yourself, and what to wear, and how to have fun, and how to have humor in the way you do things. It’s just a question of being aware. And it’ll take women ages to be aware. Really aware, and not scared and obeying.

Photo courtesy Kino Lorber.

WILLIAMS: Something that you say in the film is that, in this world, “everything is delegated to photography, and that nothing is left to one’s own memory.” Part of me empathizes with Ben, because for me, at least, the impulse to document a person or a place comes foremost from love, and people like to think that there’s truth in love. But love is also subjective, and I think even—or especially—in a documentary, emotion and memory inject their own subjectivity. Would you agree with that?

BARZINI: Sort of. I think love is hard work. It’s not something that comes from nowhere and stays there. It’s something you have to work on. Even maternal love is something complicated that you have to work on. I don’t like images because they cut out reality. It’s just like a little piece of something, and it talks about the talent of who shot that little something, and I don’t like egos and I’m not into anything that has to do with self-gratification. And that goes for cinema, too. A lot of films could also have not been shot.

WILLIAMS: You say that “the real me is not photographable.”

BARZINI: Yes. But I did show my real me to Ben. At least, the real me of that day.

WILLIAMS: There’s that old idea that when someone is photographed, a part of their soul is stolen. Is it something like that, for you? That something is taken from you?

BARZINI: No. It’s not about the soul. It’s not your soul. It’s just you. Why should you be publicized? When I said that sentence, I was thirty years younger, and it had to do with the fact that when you dress up for Vogue or some sort of editorial of some kind, you’re not you. You’re acting a part. So that makes it easy to say “nobody can photograph me” because I wasn’t photographed as me, I was photographed as the model wearing I don’t know what.

WILLIAMS: There’s that one scene where Ben has the younger models, these sorts of alternate versions of you—they’re reading your writing, and for a moment it’s almost like a Straub-Huillet film, you know, the Marxist filmmakers. He builds this montage with your journals and the archival footage. How do you feel about that technique of him recreating you through other people?

BARZINI: I feel it’s got to do with what he needed to do. It’s none of my business what he needed to do. He needed to do that so he did it. I don’t have any objections or reflections on it. It’s his thing, not mine.

WILLIAMS: Why do you think he needed to do it?

BARZINI: Well, I never asked him, but he needed to go to New York, that’s for sure. And probably he needed to show some aspect of being a photographer, not caring about people, but caring about the photos.

WILLIAMS: The film is called The Disappearance of My Mother. You talk in the film about how you don’t want to appear, and that you want to disappear, but the sentiment, towards the end, moves toward something less like an ideology and more about life itself. A way to depart from life. I was just wondering what makes you feel visible. What propels you from disappearing and gives you strength to appear?

BARZINI: Disappearing isn’t easy. It’s really very difficult. Appearing is easy. The reason why I profoundly want to disappear is that I’m sick and tired of living in this society, I dislike the value of money, and I just don’t want to see the hypocritical side of this whole ethnic group made of white men that destroy the world. I just want to not see this ever again. So I just want to disappear, and that’s it. It has to do with death because I’m old and sooner or later, I’ll die. But it also has to do with another way of considering death: without funerals, and tombs, and people crying and all this shit. Say goodbye to the people you love, and go. Great. My problem is I’m not sure where to go yet.

WILLIAMS: Well, I think the film…did you feel like it helped orient you in maybe finding that place?

BARZINI: Well, I won’t tell anybody where that place is. But I think there’s one quality of the film that I can see, and that is it’s authentic. There’s no crap. No retaking of scenes. The scenes that you see were shot like that and that’s it. So it’s very authentic in the good and the bad, and there’s no tricks. I don’t mind that. I think that’s a quality that Ben has. Making this film, it’s his life, I don’t know what he’ll be doing next. Here, it’s real.