Asghar Farhadiâ??s Character Study

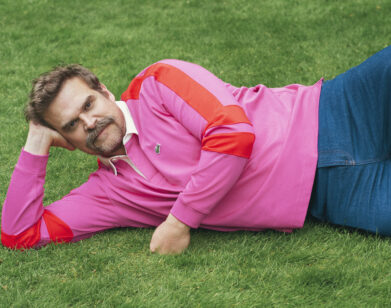

ASGHAR FARHADI IN NEW YORK, NOVEMBER 2016. PHOTO: DEAN PODMORE.

Close to the start of Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s latest film, The Salesman, a married actor couple evacuates their apartment in Tehran. Massive cracks appear in the walls, and window glass splinters, as a neighboring construction site threatens the building’s collapse. “Being fragile is something that is very close to the theme of these movies,” Farhadi concedes, speaking through a translator, about his body of work. The frailty—of human relationships, of cultural mores—is a construct that Farhadi deftly dissects with an eye attuned to the macro and micro of sociopolitical codes in contemporary Iran, most successfully in his Oscar-winning divorce drama A Separation (2011) and About Elly (2009), in which the disappearance of a single woman brings out the true character of a group of bourgeois, seemingly progressive young professionals.

The Salesman takes it name from Arthur Miller’s 1949 play Death of a Salesman, a production of which the couple in question Emad (Shahab Hosseini) and Rana (Taraneh Alidoosti) are in the midst of performing with their theater group. After Rana is sexually assaulted while alone in their new apartment, the placid nature of their relationship turns harrowing and Farhadi’s focus turns to the psychological, as Emad attempts to avenge her attack and zeros in on tracking down her assailant. Interview spoke to Farhadi in New York in November, shortly before it was announced that the film was short-listed for the Best Foreign Language category at the Oscars. On Tuesday, the nomination was made official.

COLLEEN KELSEY: I want to begin by talking about the two images that open and close the film, of the isolated stage sets, and their potency and role in the larger story of the film.

ASGHAR FARHADI: Both the first shot and the last shot of the film are related to theater. In the beginning we see the production of the house, that there are lights coming off, and at the end we see the people who are getting their makeup to go on stage. It’s a paradox. When their job is acting, it means that they have the ability to put themselves in the shoes of other people. And when they face this crisis, you ask yourself, “Are they able to put themselves in the shoes of the other characters?” They can or not. This is [where the] paradox, the idea of them being an actor and going to a theater, is coming from.

KELSEY: Developing the story for this film, what came first, the plot device of the attack, or the construction of the characters as actors?

FARHADI: The theater part came later. When I understood that the job is being an actor, then the theater came. I had a story of this couple that moved into their new house and the previous tenants would make problems for them, that somebody comes in the middle of night and really messes up their lives. I had this story in my head for years. But I was constantly thinking, “It’s not complete, it missing something,” till I had an epiphany at some point, “Oh, these people can be actors! This gives my story another layer.” Something that was very interesting for me in this project, the challenge, was that the relationship between real life and theater comes out correctly. I would love for the audience to start to doubt and ask themselves a question—”Are we watching theater right now, or is it real life?” Sometimes we feel like life is like theater, really.

KELSEY: The play Death of a Salesman—at what stage did it came into the story, and how you do you see the parallels between what these characters are acting out in relation to the narrative of their lives that we see in the film?

FARHADI: When I wrote the story of these characters, I asked myself, “What play are they doing?” I read a lot of plays until I got to Death of a Salesman, and it got me very excited, because I found so many links between my story and Death of a Salesman. Thematically, the theme of humiliation was similar in both of them. It was very interesting to me that Emad, the main character, was acting as Willy Loman, who’s the salesman in the play, and he confronts an Iranian version of Willy Loman in his life. This paradox that he couldn’t understand, or have empathy towards, that Iranian salesman was very interesting.

KELSEY: What’s your approach to psychologically creating a character who moves from normalcy or complacency to a quest for vengeance or violence?

FARHADI: Not just in this film, in any film, the character changes when you put them in a crisis situation. In normal life people look like each other. When a crisis happens, then the differences come out, and we see the different sides of those characters. Just imagine if they told you that this door is locked right now and you can’t go out for two days. Then we are not the same people that we are sitting here right now—we show our real characters. That’s what I tried to do in the character romance. They reflect or react to the crisis that they’re in the middle [of].

KELSEY: For you cinematically, what are the tools to bring together elements of realism and suspense, as we can see in this film?

FARHADI: These are things that you see, if you write it on paper or in theory, seem like they can’t get together. We always have the movies that are more toward real life, but they don’t have that much drama or suspense, or we have the full of drama or suspense, but they’re far away from real life. Always when I was watching a film, films with good drama, I was thinking, “I wish they were more close to real life.” But when I was watching real life films I was thinking, “Well I wish it had more drama.” I’ve tried, in the movies that I worked so far, to get these two things closer and closer to each other.

KELSEY: I also wanted to talk about the tension between the push for modernity and its relationship with tradition, which comes out in the relationship of the characters, but also even in the literal architecture of where they are living.

FARHADI: I always thought that in the countries that the modernity kicks in later, it seems that everything changes on the surface, the physical things change, but inside, things haven’t changed, really. This is always the challenge of this kind of community, to make a harmony between the cultural traditions and the modernity of modern life. Whether we like it or not, the modernity is something that comes from Western countries, and when the modernity comes to the Eastern countries, although they feel like they really need it, at the same time it shakes the very fundament of the culture—there is always this challenge between the two.

THE SALESMAN IS OUT TODAY IN LIMITED RELEASE.