André Singer and the Allies’ Long Lost Holocaust Documentary

ABOVE: A STILL FROM NIGHT WILL FALL. PHOTO COURTESY OF IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM/HBO

In 1945, the Allies commissioned a documentary of the Holocaust. Helmed by Sidney Bernstein and produced by the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, the film bore the unglamorous title German Concentration Camps Factual Survey. It featured graphic, gruesome footage shot by American and British soldiers at the liberation of the Nazi work camps Bergen-Belsen and Dachau, the discovery of warehouses full of human hair and human teeth, and decaying, naked bodies of men, women, and children left strewn across the ground or contorted into giant piles. By the time it was ready for release, however, the Cold War was just beginning, and Britain and the U.S. needed a healthy Germany as an ally against the Soviets. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was never released.

The Holocaust is slipping out of living memory—each year, the number of survivors who gather at the former death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau on Holocaust Memorial Day dwindles. Recently, however, the Imperial War Museum in London restored and digitized Bernstein’s original documentary and anthropologist André Singer was invited to turn it into a new film. Titled Night Will Fall and set to premiere Monday on HBO, Singer’s film brings the Holocaust back into a visceral reality. In addition to the footage from German Concentration Camps, Singer adds interviews with British soldiers and cameramen, the original film’s editors in London, and survivors of the camps themselves. “The people who tell the story in the film are those who were there and are still with us,” explains Singer. “This is a kind of last generation that is able to witness and tell us, and they’re part of us,” he continues. “That it’s not distant history… it’s very dangerous for us to think of it as something in the distant past and not relevant to today’s society.”

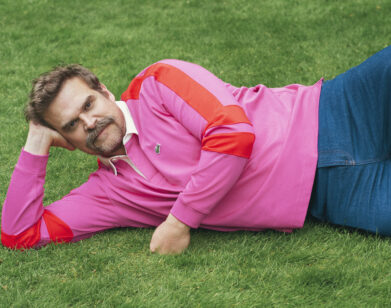

We spoke with Singer, who has previously produced documentaries such as The Act of Killing and Werner Herzog’s Into the Abyss, just before Night Will Fall had its first New York screening.

EMMA BROWN: When did you first hear about this footage and this film that was never finished?

ANDRÉ SINGER: It was a project brought to me by a producer who had been working at the Imperial War Museum, Sally Angel. She had been watching the curator and the historians are the Imperial War Museum put together the original footage from 1945. Because my company specializes in sort of bigger documentaries, she brought it to us to see if we could structure a film from it. I went and viewed the material and was dutifully shocked and appalled by it, but we jointly thought there was a very good film to be made here, a different film. A film about imagery and film telling the story of the Holocaust rather than a straightforward historical film.

[Some of the] footage in that [original] film has been shown in different contexts, at different times, because it’s material that was owned by the British and American governments, and the Soviets. That government material has been accessed by different filmmakers and documentary makers, so clips of it have been seen, but never as a proper film, and some of it is new to audiences as well. What makes it very different now, and what makes it more shocking, is that when you digitize the original [footage], what appeared to be very grainy, distant, historical footage, suddenly becomes very, very real. It is extraordinarily horrific material.

BROWN: When I watched the documentary, I knew it was going to be very upsetting, but I still didn’t feel prepared for how visceral and graphic some of the footage is. I felt sort of like someone should have warned me, but at the same time, obviously a film about the Holocaust is going to be awful.

SINGER: I think there’s a very major and sensitive issue about any atrocity footage, and it is a matter of debate as to whether people should even see footage like that. I am strongly, clearly, of the belief that it’s important because it’s visual evidence of things that we can only ever intellectualize or speculate about. People have to understand that this is real, and these are real people, and this is real barbarism that was happening in 1945. There’s a major debate going on with educationalists about how old you should be in order to see a film like this, but I am firmly of the belief that if you show and access footage like this—atrocity footage—out of context, which kids see by pressing two buttons on the internet, it becomes a kind of atrocity pornography. But if you put it in context, it has a hugely important role to play in teaching people about the reality of what mankind can do to fellow humans. That’s one of the most interesting and contentious things, not just about our film, but about using film and imagery like that in order to teach or to learn about the Holocaust itself.

BROWN: Do you think it can prevent something like that from happening again?

SINGER: I would love to be able to say yes to that question because that’s obviously the most important question of all: why are we doing it otherwise? At the end of the original film, which has a very lyrical script, was the quote by Richard Crossman: “If we don’t learn from these images then surely night will fall. By God’s grace, we who have survived will learn.” The whole moral of that film in 1945 was that you have to show people this material in order to shock them into stopping it ever happening again. And it’s what Bernstein, who created the film, said should be a lesson to all mankind. Of course we haven’t really learned, because there are something like 20 genocides, according to the United Nations, that have happened since then. So it’s a moot point as to whether that particular lesson has been learned or not. But I’m hoping that in this resurgence of anti-Semitism and intolerance and fundamentalism that we’re seeing now, that this material can at least help show how dangerous it is to allow it to slip. So, in a small way, perhaps it will help. Realistically, I suppose, we have to be slightly skeptical because this is what mankind is capable of doing to each other.

BROWN: One moment I found so interesting in Night Will Fall is when some of the Holocaust survivors you interviewed talked about re-enacting the moment of liberation so that the Russian army could film it.

SINGER: Oh yeah, that was extraordinary. The problem was that when the British and Americans went into the camps, they were there at the time and they filmed actuality. It was observational film, really. When the Russians went in to liberate Auschwitz, they didn’t have cameras with them. So they liberated the camps, realized how important it was, how extraordinary, and sent for the cameras, but the cameras only came about a week later. They didn’t want to miss doing something important, because they also realized they’d need these materials for war crimes and other things. So they asked the inmates to restage some of the things. It was a slightly different perspective you had from the Russian materials than you did from the Americans or the British. It wasn’t invented, but they asked people to put back on their pajama-type costumes, and walk here and walk there and do this and do that. It was a very different set of circumstances.

BROWN: That’s got to be a traumatizing thing to reenact, you think you’re free and then all the sudden you’re being ordered around.

SINGER: Oh, absolutely. Probably it’s even more traumatic looking back than it was at the time. Back then there was a certain level of euphoria: they’d just been liberated, and doing something for the Russians, who were their liberators, that was fine. Nobody complained about it to me.

BROWN: Do you still think of yourself as an anthropologist or a documentary film producer first?

SINGER: I have a double-track life. I’m not quite sure how else to explain it because I am president of the Royal Anthropological Institute in the U.K., so I do have an anthropology role, and I am also attached to the Department of Anthropology at USC in Los Angeles. I do keep going as an anthropologist but I think my livelihood and my real passion lies in filmmaking.

I think part of the reason I find myself having this sort of grand title of ‘President’ is because anthropology itself is looking, and has been looking, for more social relevance, and how we behave and looking at prejudice and intolerance and so on, is anthropological. They are important for all of us. So I’m finding rather encouragingly that there is a merging between those two worlds, and anthropology has a huge part to play, I would hope, in the progress of society. It’s not an anomaly anymore; it’s actually rather an important subject in today’s age. You look at what’s happening around the world—somehow we have to understand it all and I think anthropologists have a major role to play in that.

BROWN: How do you want Night Will Fall to be used in the future?

SINGER: I would like to feel that this is not just a one-showing on television, but that it has a life going forward. I think it’s the sort of subject that needs to have a life going forward—not just the film itself, but the material in the film, the interviews of the people in the film, should be used in different contexts as education.

NIGHT WILL FALL WILL AIR ON HBO MONDAY, JANUARY 26, THE DAY BEFORE HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL DAY.