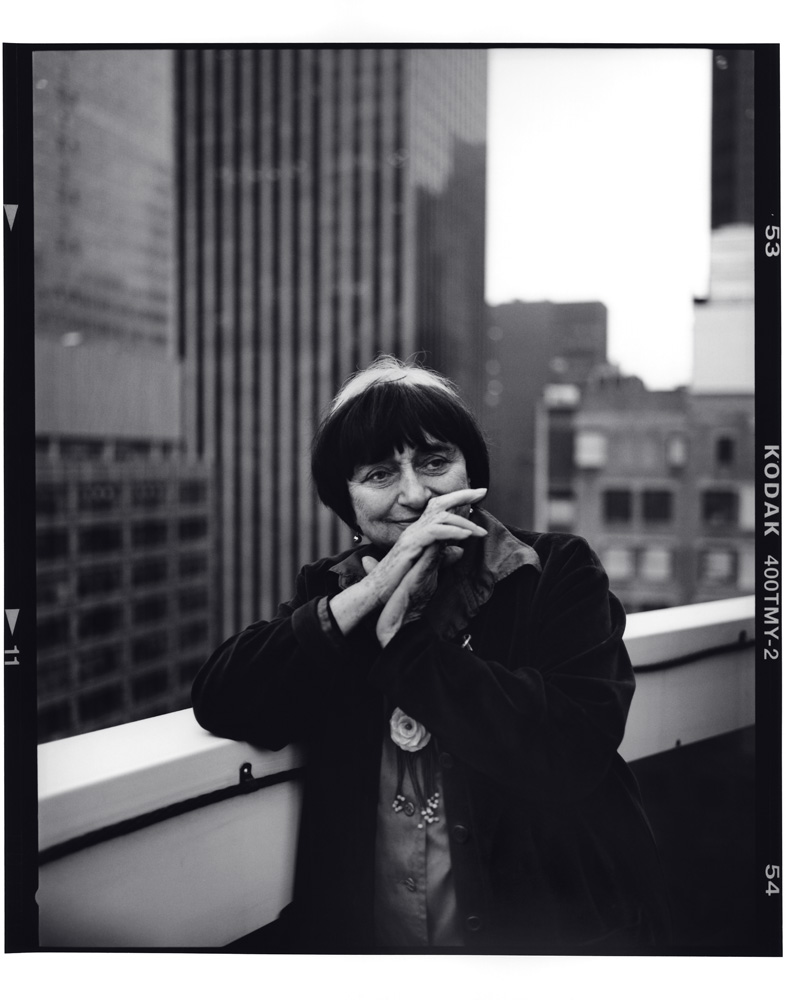

Agnès Varda

Never mind the ravages of time. Filmmakers seem to be exempt. In her winsome, haunting self-portrait, The Beaches of Agnès, which is released theatrically on July 1, French director Agnès Varda has retained all the vitality, humor, and sheer cinematic inventiveness that has marked her films since 1954’s seminal La Pointe Courte, which she made on a shoestring budget at the age of 25. She’d always wanted to sail to Paris-well, in Beaches, she does. We see her coolly navigating a small dinghy under the Pont Neuf along the Seine. She treats the film as an opportunity for playful wish fulfillment as well as for analysing her life experiences, her filmic hits . . . and the odd miss.Hailed as a precursor to the Nouvelle Vague, La Pointe Courte, her black-and-white debut feature, was a neorealist love story with parallel subplots set in a Mediterranean fishing village. She revisits that location in the new film, providing a moving tribute to the locals who, in acting out their life stories, had helped launch her career. The appreciation is mutual. In Sète, they’ve named a street after her.

Spanning half a century, Varda’s career includes the landmark real-time drama Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), about a pop singer awaiting the results of a cancer test (a priceless cameo shows a diffident Jean-Luc Godard removing his sunglasses); Le Bonheur (1965), a stylized melodrama concerning the unintended fallout from adultery; Vagabond (1985), starring the 18-year-old Sandrine Bonnaire as a homeless free spirit, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival; and two documentaries devoted to her late husband, director Jacques Demy: Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and The World of Jacques Demy (1995).

Walking backward (literally) into her past without a misstep, and using the beach as a springboard for her memories and reveries, Varda deftly intercuts photographs and archival footage with clips from her films and reenactments. Revealing a life inextricably mixed with art, through an ingenious juxtaposition of images and wordplay, Beaches is a fascinating demonstration of imagination at work, of fact morphing into fiction. Full of self-deprecating wit, wisdom and whimsy, the film shows her transition from photographer to filmmaker; her stark early working conditions; her travels to Cuba and China as a photojournalist; and, later, to Los Angeles with Demy. Inviting a troupe of trapeze artists to Sete beach, she’s not afraid to show her taste for the populist circus as much as her love for ancient art, which she studied at Ecole du Louvre.

After the international success of The Gleaners and I (2000), a personal documentary essay about people who live on others’ leftovers, Varda reinvented herself as a video-installation artist. The Beaches of Agnès won the French Union of Film Critics’ prize for best film in 2008 and the César for best documentary this year. Despite her demanding travel schedule, in person Varda is no less sharp-eyed, vivacious, or considerate than in her film.

[March 9, 2009. An office on the fifth floor of the French Embassy, New York, after a lunch in honor of the filmmakers participating in Rendez-Vous with French Cinema 2009, where The Beaches of Agnès is being shown. Varda is seated behind a desk facing the interviewer. She and Liza Béar talk between phone calls.]

AGNèS VARDA: [hanging up the phone] I’m having an exhibition in Boston.

LIZA BEAR: Formidable! Where?

VARDA: At the Carpenter Visual Arts Center.

BEAR: I noticed you did Patatutopia at the Venice Biennale in 2003 with 700 kilos of potatoes.

VARDA: Yes. Listen, is it okay if we talk in French? Speaking French is more restful.

BEAR; Oui. Vous voulez de l’eau? [From now on, the dialogue is in French.]

VARDA: You know, the boundaries between contemporary art and cinema are so rigid. It’s unbelievable. The film critics don’t know my artwork and the art world doesn’t know my films. I had a very big show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris with seven or eight video installations. At Harvard, I’m showing just one, The Widows of Noirmoutier. It’s 15 screens about the collective and individual experience of mourning. Installations-my new life. I’m very happy that MoMA bought one of them. [looking across the desktop] Ah, I see you have a little package there. Looks like note cards.

BEAR: Well, a literary agency on Bond Street went bust and threw their stationery out on the curb. That’s how I got these cards.

VARDA: You are a gleaner. By the way, buying stuff cheap at a flea market is not gleaning. Gleaning is reclaiming what others have discarded.

BEAR: It was fascinating to watch your films again. I first saw Cléo from 5 to 7 in the ’60s, but to see it now, after seeing Beaches . . .

VARDA: See how everything crisscrosses?

BEAR: I watched it with my son.

VARDA: How old is he?

BEAR: Twenty-eight.

VARDA: Then he had to see it.

BEAR: The opening sequence of Cléo is a scene with a nécromancienne . . .

VARDA: A cartomancienne [fortune-teller]. She has tarot cards. I see. You wanted to make question cards. Very good. [Béar laughs] So lay out your cards! This is very amusing. Don’t put out too many. Four up, four down. Allez, hop! Here goes: [reading from a card] “At 18 years old, I bought a train ticket to Marseille and a boat ticket to Corsica without telling anyone.” It’s a quote from the film, not a question!

BEAR: I know. I’m off questions. It’s a prompt.

VARDA: My response is that my son wouldn’t believe I did that.

BEAR: When World War II broke out, your parents and four siblings joined the exodus from your native Belgium and took refuge on your father’s sailboat at Sète, a small port on the Mediterranean. And as a teenager you hung out with the fishermen and learned how to mend fishing nets.

VARDA: That skill came in handy when I ran away to Corsica, much more than my high school diploma. It helped me to get a job. While making Beaches, I got lucky, because in Sète I found a 16mm home movie about the old man who had taught me how to mend nets. It was logical to put that scene in my film.

BEAR: We see you rowing a small dinghy.

VARDA: The original boat was much bigger-it held four guys. The job I got in Corsica was ferrying fishermen out to sea. But at 18, I could row much farther than I can now at 80. Here I wasn’t doing an exact reenactment, it was more like evoking the past.

BEAR: Another beach that you filmed on was Noirmoutier.

VARDA: That’s an island facing Nantes on the west coast of France where my husband, the director Jacques Demy, grew up. He wanted us to settle there. We converted an old windmill for living and working. We spent a lot of time there. When Jacques died, I made a movie about him, Jacquot de Nantes-as a widow, it was my way of structuring or finding a form for my grief. A lot of sailors and fishermen from those islands die at sea. So some years later I started to talk to and film other widows mourning their husbands. Longtime widows and recent ones. Talking to them was very moving.

BEAR: Your mother bought you your first serious camera, a used Rolleiflex, in Sète.

VARDA: Yes. But in the film I also mention that my mother was losing her memory. I’m losing mine now, more or less. Everyone does. At least what’s in the film won’t be forgotten. And I’m paying homage to two women: One is the 94-year-old widow of Jean Vilar, the theater director I worked for as a photographer. She can’t remember where she is or if she’s eaten, but she can recite beautiful poetry by Valéry and Racine. The other is my mother. She would make mistakes, but I would say, “Let her be. She’s free.” Because forgetting is a form of freedom. Loss of memory is a subtext throughout Beaches. Oh, the cards! [reading another card] “Nausicaa, Gérard Depardieu, beatnik . . .” Well, that film has disappeared. It was shot in 1970, when Depardieu was very young. Handsome, isn’t he? Already a great actor. He used to visit our house in Paris a lot and once or twice he babysat my daughter Rosalie.

BEAR: Were some moments of your life hard to revisit in the film?

VARDA: Yes. As I walk backward on the Santa Monica pier I say, “Memories are like flies swarming around me and I’m not sure I want to remember.” I had accompanied Jacques to Los Angeles when he was making a Hollywood film, and there were some rough times. Later we made up and decided to grow old together-a great project that was cut short.

BEAR: But in fact you got to make several films in Los Angeles: Lions Love [1969], Black Panthers [1968], and Mur, Murs [1981]. Would you like another card?

VARDA: Yes, one more. I like the cards. I like your game. [Béar puts down more cards.] Don’t look at them!

BEAR: I’m not! [Varda chooses. She doesn’t recognize the lyrics on the card from a French song about a camel but instead sings a song from her new film about a nightingale.]

VARDA: It’s funny asking a nightingale to teach you the language of love, don’t you think?

BEAR: Well, it’s the most beautiful of bird songs. But now other birds are singing at night because there’s too much traffic in the daytime.

VARDA: In my courtyard in Montparnasse they are singing a lot less than they used to.

BEAR: In 1951 you found this wonderful abandoned building with a courtyard between a former grocery and a frame shop.

VARDA: Yes, and I still live there. But now it has flowering shrubs. It’s a bit House & Garden. When I moved in, it was a wreck. No heat, no bathtub or shower. Just a basic Turkish-style toilet.

BEAR: A hole in the ground.

VARDA: I lived there for four or five years without paying rent. For Beaches, an artist, Franckie Diago, reconstructed the courtyard in its original dilapidated state. She had been my set decorator for One Sings, the Other Doesn’t in 1977, a story about abortion rights.

BEAR: How did you get Alain Resnais to edit your very first film, La Pointe Courte? It was before he made Hiroshima, Mon Amour [1959] and Night and Fog [1955].

VARDA: He had already made two documentaries, one with Chris Marker about African art called Statues Also Die [1953], and another about van Gogh, at a time when everyone worked in black-and-white. Resnais was an editor. I had to persuade him to work without pay, like the others. We had a production co-op, which wasn’t standard at the time.

BEAR: How did that work?

VARDA: There are two kinds of capital: money and work. I had a small inheritance and my mother added a little more. Then I gave a value to the sweat equity. If we raised 100 francs, 50 percent went to reimburse the financing, and 50 percent went to the cast and crew. No commission, no contingency. I would have loved for La Pointe Courte to be a success.

BEAR: But it was a critical success.

VARDA: Well, for selected audiences. It was immediately shown in cinematheques everywhere, but, regretfully, it made no money whatsoever.

BEAR: In Beaches you found really touching ways to introduce us to some of the local people in your films who had worked with you and to show your appreciation onscreen . . .

VARDA: Exactly.

BEAR: There’s another scene in Sete where you find Dédé, now an adult man, who played the little boy who ran from the dining table. His mother said, “Dédé, eat your grapes.”

VARDA: What a memory! That’s what we call him now, Dédé-take-your-grapes!

BEAR: How did you persuade those fishermen’s families to be in La Pointe Courte?

VARDA: I must have spent about 15 summers in Sète, so I got to know the locals. Every evening I would write down bits of conversation I had heard-I had no tape recorder. I didn’t take notes on the spot because I didn’t want to look like a journalist. I wanted to be friendly. Then, later, back in Paris, I wrote a script based on my notes. I wanted to recount my memories and to honor those who made me who I am. I’m not Madame Agnès with her loves and her children. It’s my life story as a filmmaker, seen through the eyes of a filmmaker.

BEAR: Makes sense.

VARDA: As I see it, to use a cinematic approach or framework means finding a form for each idea you have. The best example is from La Pointe Courte. I had done a screen test with two friends, Pierre and Suzanne Fournier. Pierre died. Later, the real scene was acted by Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort. But the Fourniers’ two sons had never seen the test scene of their father onscreen.

BEAR: So Beaches enabled them to do that.

VARDA: Yes. I rigged up a 16mm projector and screen on a wooden cart and projected the test footage of their father while the boys pushed the cart through the streets. It was like a funeral procession, a phantom carriage-a film within a film.

BEAR: All these little scenes have a special character. I thought you worked wonders of merging the chronological sequence . . .

VARDA: And breaking it.

BEAR: . . .breaking it thematically. I mean, there are natural segues from topic to topic, and then, bam! all of a sudden there’s a historical date, so that we get our bearings.

VARDA: So you understand. The chronology’s there, but an emotion will throw it off. Here’s another example: I had been a photographer for Jean Vilar, director of the Theatre National Populaire. At the time I was making Beaches, they offered me a big exhibition in Avignon of photos I had shot there from 1950. The prints were 5 meters high-everyone was complimenting me. But all I could think of was that these marvelous actors, Gerard Philipe, Jean Vilar, Philippe Noiret were dead. . .Suddenly I felt a pang of emotion which led me back to the death of Jacques.

So there’s an emotional fluidity to the film, several points of access . . .

BEAR: You have many strings to your bow.

VARDA: In another sense, the film is about one little person’s creative life across half a century that saw the Cuban Revolution, the Chinese Revolution, the Black Panthers, the evolution of birth control-major social changes.

BEAR: Many of which you worked into your films.

VARDA: And also the growth of popular theater and of the nouvelle vague. It’s my trajectory through public events, either by chance, by affection, by political conviction . . .

BEAR: Or imagination. What was the Manifesto of the 343 Bitches?

VARDA: Well, a right-wing magazine came up with that title, not us. Around 1970 I signed the Manifesto with other women because of a specific instance of class injustice. In France at the time, working-class women who had abortions went to jail, while the bourgeois ladies who had money went to Switzerland. Not fair. The Manifesto stated, “We’ve had abortions: Judge us.” In Beaches you see the women protesters shouting that. So we thought, if well-known people signed, like Simone de Beauvoir, Delphine Seyrig, Marguerite Duras, Françoise Sagan, then when we went to trial it would embarrass the judges. This petition affected the outcome of a famous French trial and led to the passing of an abortion rights law in 1975..

BEAR: How did you meet Shirley Clarke, who plays the documentary filmmaker in

Lions’ Love (and Lies)?

VARDA: Oh, I met all the experimental filmmakers in the 60s, Michael Snow, Robert Breer, Ed Emshwiller, and Brakhage, who filmed his wife giving birth. And I loved Andy’s films, Nude Restaurant and Lonesome Cowboy. Andy, who admired Cléo so much, invited me to the Factory and introduced me to Viva. Andy was impressed by the Nouvelle Vague. So were Coppola and Scorsese. Because we started experimenting before them.

BEAR: According to you, how did the Nouvelle Vague get started?

VARDA: What’s not widely known is that the cine-clubs played a very important role in establishing the concept of an auteur. Until the 50s, you went to the movies in France to see a film with Jean Gabin, Martine Carol, Simone Simon, actors of the period. But the cine-clubs showed films by Renoir and Murnau and emphasized the director’s sensibility. So when the Nouvelle Vague arrived, everyone accepted they were watching a film by Godard or Varda, not a Jean Seberg film. And of course, Cahiers du Cinema subsequently developed this notion, la politique des auteurs.

BEAR: What’s this business about right-bank and left-bank filmmakers?

VARDA: Left-bank is a term invented by Richard Roud. In fact, Chris Marker, Resnais, and I, who had our hearts on the left politically, lived on the real Left Bank in Paris. But since that time, I like to branch out. I don’t like to repeat myself. [phone rings] Hello? Radio Canada? Can you give me 10 minutes? [covering mouthpiece] My film is opening in Canada on the 13th. No? I’ll stay on the line then . . . The tool of every self-portrait is the mirror. You see yourself in it. Turn it the other way, and you see the world . . .(reading a note from Béar) My friend here reminds me that Sartre said, “Hell is other people.” Well, I don’t agree with Sartre. I like others. My film could use Gertrude Stein’s title, Everybody’s Autobiography.

Liza Béar is a New York-based filmmaker and the author of Beyond the Frame: Dialogues with World Filmmakers.