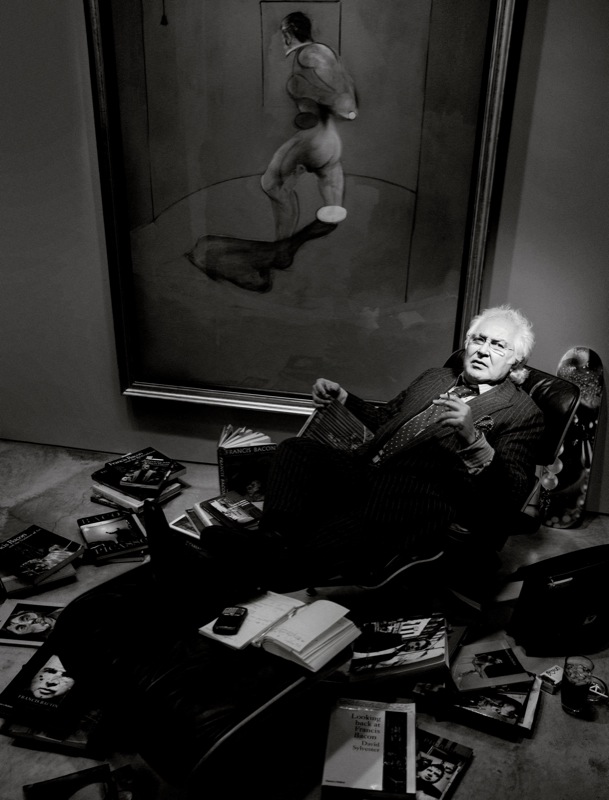

Tony Shafrazi

Tony Shafrazi is one of the world’s best-known art dealers. He doesn’t sell the most art; he isn’t the most social dealer or the richest; but he may be the most artistic. He’s the closest thing we have to a legendary dealer today-so much so that artist Urs Fischer and art dealer Gavin Brown mounted an extraordinary exhibition at Tony Shafrazi Gallery this past summer that served as a visual and intellectual biography of a man who has lived a life that is literally fabulous. The Iranian-born Shafrazi began his career as an artist, and, even in his life as an art dealer, he maintains a practice of reading, learning, thinking, and discussing that demonstrates that with art there can be transformative creativity even in the marketplace. Anyone who knows Shafrazi knows that he is a real character, one of the great talkers. He talked to his good friend Owen Wilson for hours and hours-and here are some of the highlights.

OWEN WILSON: You once said to me that if it weren’t for art then you’d probably have become a bank robber.

TONY SHAFRAZI: Yeah, or something close to that. The image of the bank robber I had in mind was more in the European tradition where you’d rob banks and give to the poor, like Robin Hood. It was that mythology. But very early on, my whole preoccupation was with art-studying it, examining every piece of work. At 7 or 8 years old, a couple of friends and I sort of created a little art thing. We bought some paints and canvases and started making work. By the time I was 11 or 12, I was already making paintings in the styles of Dalí and Van Gogh. And then, when I was 13, my father and stepmother took me to England and left me to study there. I first went to a vicarage in Bilston and lived with a priest and his wife for a year and a half. Then to boarding school for two and a half years and then Hammersmith College of Art & Building for four years. And then I went to the Royal College of Art from 1963 to 1967. It was a long education.

OW: It seems to be part of the Shafrazi luck, being in the right place at the right time, because there you are, right in the middle of the swinging ’60s in London.

TS: Well, actually, I felt a little cheated because all I wanted to do since I was 6 years old was go to New York, but my father wanted me to have an English education. So England was sort of a far cry from the romance of America that I had in mind-especially going to a vicarage and going through those miserable, shivering, damp winters. But, luckily, by the late ’50s, something was happening in England, and it got to be quite exciting. The music world then started to explode with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. It was an incredible time with this mixture of independence in art, fashion, and the explosion of the pop sensibility. London was certainly at the center of it all for a few years. And as far as art is concerned, I think that sensibility of what was later called Pop art started in England even before America. So I was lucky to be there. But I was dying to come to America.

OW: When did you first come to New York?

TS: In the summer of ’65. I got a visa to come over to the States to visit my mom, who was living in Hollywood. She’s still there. In those days, there was a thing called British Caledonian Airlines, and you could fly across the Atlantic inexpensively. They even put you up in a hotel the night you arrived. Then I looked up the Greyhound bus, and you could travel all across America on this thing called 99 Days for 99 Dollars. And that was all great since I had to go to Hollywood anyway. So I decided to fly to New York City, where I stayed in the hotel the first night, and then I was advised to go stay at a YMCA.

OW: Was that a nice place to stay back then?

TS: Yeah. Back then it was all-American, and New York City was a whole different world. Anyhow, my room at the Y was on the fourth floor, and I remember putting down my suitcase and looking out the window and seeing some people on the fire escape across the street. I realized that it was Andy Warhol’s Factory. So I went up to the Factory, and I remember Andy coming to the elevator and seeing me dressed up in this little mod, shiny, mohair suit . . .

OW: Wait! How did we get from looking out your window at the Y to riding up the elevator in a mod suit to go to the Factory? Did you already know people at the Factory? Or did you just go up there cold?

TS: No, I didn’t know anybody there. I just knew that it was the Factory. I think that year it had just been painted silver, so I had seen pictures of it in the papers. Andy Warhol was like my god already. So I went downstairs and across the street. The building that the Factory was in had one of those manual elevators, right? And there were four or five other people inside when I got on. Gerard Malanga allowed me to come up, and when the doors opened I saw Andy coming toward me. He said, “Gee, who’s this?” So I introduced myself and he said, “Gee, where are you staying?” I pointed to the window across the street. “Oh gee, where are you from?” I said, “London.” And he said, “Oh, great. Would you like to have a sandwich?” And he got me a Coke and a sandwich and showed me around. I remember there were these tall, leaning pictures of Elvis from the movie Love Me Tender [1956].

OW: So it’s your first day ever in New York City, and you meet Andy Warhol.

TS: Exactly.

OW: At this point, you were an artist yourself. Was this a visit, or were you planning to move to New York?

TS: To visit. I went to New York first, and then I spent a few weeks on the bus going to L.A. Along the way, I got off at Chicago and checked out the art school there [the Art Institute of Chicago]. I stopped in places like Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Knoxville, Tennessee-places I’d heard about in songs. I would just arrive in a town and walk around. If I liked the place, I’d stay the night. If not, I’d get on a bus and go to the next place. I made many stops along the way until I came to Las Vegas, where I stayed two or three days and lost all my money gambling. Then I arrived in L.A., and my mom came to pick me up in her new green Cadillac at the bus station.

OW: So you were a horrible gambler even then?

TS: Yeah, well, in London we were already gambling in cool gambling clubs by the age of 17 or 18.

OW: The problem with you and gambling is that you have this gift of having such hope, and unfortunately it’s the cynical people who make good gamblers. You’re always hoping for that impossible card.

TS: Most of the time I gamble just for the fun of it, for the romance of it. It was always cool, especially in London, with characters like Christine Keeler, Raymond Nash, Peter Rachman, and Mandy Rice-Davies and a few movie stars around.

OW: So what happened with Andy?

TS: Anyway, that day when I went up to the Factory, Andy kind of warmed to me when he found out I was an artist, so I stayed there for two or three hours. He said, “So what are you going to do this afternoon?” and I said, “I have nothing.” And I walked over to where he was working. He was trying to fill these silver pillows with helium so that they’d float as part of an installation. He was trying to attach the part that stops the gas from coming out of the pillow-I think it’s called the nipple. I’d been making these sculptures in England using plastic and a heat-seal gun, and I could do it really well, so I said, “Let me show you.” And I showed him how to attach it with the heat gun, very cleanly. I wound up staying all afternoon. Then at one point I said, “Can I use the phone?” And he said, “Sure.” There was a pay phone in one corner all sprayed silver. It took a nickel to make a call.

OW: There was a pay phone in the Factory?

TS: Yeah, a pay phone. So I had a number-I don’t know how I got this number-but on my first day in New York, at the Factory, as I dropped a coin in the pay phone and began to dial the number, I saw Andy coming closer so he could eavesdrop. I was calling my other hero, Roy Lichtenstein. So Roy answered the phone, and I introduced myself-

OW: How did you have Roy Lichtenstein’s number?

TS: I don’t know how I got it. I have no idea. I remember that I had it on a small piece of paper.

OW: So you’re on the phone with Roy Lichtenstein . . .

TS: And I mumbled a few words about being a young artist from London and how I loved his work. And he said, “Well, what are you doing for lunch tomorrow?” And, of course, I was doing nothing. He said, “Why don’t you come by my studio.” And he gave me the address. So the next day I went by Roy’s studio and saw these wonderful paintings he was working on of large cartoon brush strokes with Benday dots. And then, around mid-afternoon, somebody brought over a project that Roy was working on with these cups and saucers that were glued together. Roy said, “Are you free this afternoon?” And I said, “Yeah, of course I’m free!” And I helped him carry some of these things out of his studio. We took a taxi uptown-I didn’t know where we were going-and we got off somewhere and then went upstairs. It turned out to be the Castelli Gallery. As we were walking in, this skinny, smallish, but beautifully dressed gentleman walked out all bright-eyed and with open arms, excited to see Roy. It was Leo Castelli. Roy, carrying these things, turned and introduced me and said, “This is a young artist from London, Tony Shafrazi.” And Leo said with this great accent, “Well, any friend of Roy’s is a friend of mine. Welcome to my gallery.”

OW: And this is all in one day that you’ve gone from Andy Warhol to Roy Lichtenstein to Leo Castelli.

TS: Almost 24 hours exactly.

OW: Tell me about Leo Castelli. He was sort of a mentor to you.

TS: Absolutely. He was like a father figure to me.

OW: He helped you make the transition from being an artist to becoming an art dealer.

TS: He probably had to do with it. I admired, loved, worshipped Castelli. He helped me-and I helped him-a great deal. I put a number of his artists in museums at a time when, economically, they were in dire need. He was a role model. What happened was that when I finally moved to America in ’68 or ’69, the social climate had changed dramatically since my first visit. With the Vietnam War, the whole business of art-making had begun to shift from making interesting paintings or objects to investigating different modes of being in the world, from the kind of monolithic pathways of the older era, which came out of the European tradition to pounding the pavement to find the American voices in art and exploring what later got to be called the postmodern era. And I felt at a certain point that my contribution could be to open up the parameters of what art was. I felt like it was important to acknowledge this new variety of voices, and that’s when the idea of opening a gallery started to evolve. So I didn’t start the gallery with the idea of being a dealer to make money. In the mid-’70s, I volunteered and spent four years as an advisor to the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in Iran and to architect Kamran Diba, so I was going back and forth building this collection of contemporary art. The idea was to put Tehran and the beautiful country and people on the map. And, you know, working with a museum, one is forced to deal with the bigger names, but I also felt that there were younger voices and energies that represented the undercurrent of youth and needed to be heard. I opened my first gallery in Tehran with tanks in the streets and martial law, and I lost everything. And, in early ’79, I opened a gallery in New York, and soon after, I was able to bring my father and stepmother out of Iran. Then I introduced my dad to Leo Castelli. Within a year or two, I had some of the better artists of our time: Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Donald Baechler, Kenny Scharf, James Brown, Ronnie Cutrone, and a number of others who started to become quite well-known. My idea was to create an arena so that new voices and new talent could come along and question the old ways of seeing.

OW: How did you find people like Haring and Basquiat, because they could not have been bigger outsiders? Although they were both in New York . . .

TS: Well, a lot of people gravitated toward New York at the time, but they were both developing original voices. I showed many different people like that-I can’t list everybody.

OW: Do you think being from Iran and an outsider yourself sharpened your eye as an art dealer?

TS: Yes. This is why, today, I think the true definition of so-called postmodernism is the acceptance that we cannot go by old models any longer. The old models were based upon a single narrative of development that happened along a singular path. In the 20th century, you have electricity, you have transportation by plane, you have the telephone and all the various media that developed, you have a multiplicity of places, a multiplicity of events and voices and creativities that are happening all around the world-and that multiplicity escalated after the war. It certainly escalated by the mid-’50s, with rock ‘n’ roll and the arrival of the new generation of filmmakers and artists and actors. There was a new voice, a new energy that evolved, and within that there were individual voices that came from the underground. For me, being Christian Armenian, born into the Islamic culture in Iran and then, at the age of 13, being sent to England and embracing the English culture and becoming part of so-called swinging London and the era of euphoria and celebration that the ’60s represented is very critical. It was a moment when, for the first time, the business of internationalism was being effectively represented-in music, art, cinema, design. Before that, everything was directed toward these monolithic forces, toward the old industry, the old school, the old regime, the old format, and there was no room for varieties to evolve. So the breakdown of the modern movement led to what later became known as postmodern-whatever the hell that means-referring to the mixture of people and backgrounds that became a common thing among artists in America. Many of the great artists in America, for example, came from Jewish families and backgrounds that fled all the way from Russia. It’s remarkable, the great masters of American art and cinema who were coming from old roots in little villages there. And then Hollywood, and the haunting, hypnotic impact that American Cinema had throughout the world . . .

OW: If you were in the U.S. Senate, do you think one of your strengths would be filibustering? [Shafrazi laughs] You’re unbelievable! I can’t even remember what question you’re answering! All of a sudden we’re talking about little hamlets in Russia, and I don’t know how we got there! Do you remember what my question was?

TS: Yeah, you were talking about whether the multicultural background that I come from has had any impact on my identity.

OW: Whether you think it has sharpened your eye.

TS: Yeah, it has sharpened my eye. Absolutely.

OW: Okay. [both laugh] You know, you and I have known each other for 10 years, but we’ve never really talked about the day that you spray-painted Guernica.

TS: Oh, yes, another part of the rich and varied history that I seem to be living.

OW: Talk about that.

TS: Boy, that’s going to take another three hours.

OW: Well, give the short version then. When you spray-painted Guernica, the idea was that you were protesting what was going on with Vietnam, right?

TS: Well, there were a number of other things involved, but the Vietnam War was undoubtedly the background and the reality. You have to understand that it was something that no one today could possibly imagine-the constant, perpetual destruction of the war-and, of course, seeing it daily on color television and the implosive effect that it had. It really fractured any of the old ’50s assumptions of what institutions were about and the faith that one put into them. Up until the mid-’60s, there were still lynchings going on in the South. When I was in Los Angeles, I watched the Watts Riots. There were the assassinations, one after another. We also had Watergate, so even the government and the roots of democracy were being questioned and undermined. Every artist, every artwork that was attempting to do something new was addressing those issues. In my case, I felt that if Guernica could speak, then it would scream, and my own interests were moving away from objects and paintings to activities and art actions. I was interested in the idea of how one could enhance something by adding to it or altering it-which was not really a new idea since artists like [Marcel] Duchamp and [Robert] Rauschenberg and various others had done things like that. But some crazy notion came to me that here we have the greatest painting that the greatest artist of our time, Pablo Picasso, ever painted, Guernica-which is an absolute masterpiece, the greatest depiction of the horrors of war, questioning the stance of the government in Spain in dealing with the bombings that had taken place in a village in Basque country-and it was assumed to have been digested and to have had its effect and to no longer have any impact. And yet the horrors of war at that time were exaggerated on such a massive scale that art had no effect whatsoever. But art does have a central place in life-it’s a tool, a weapon-and it was being treated as if it was irrelevant, ineffective, nothing. So I felt that by doing something, by writing across the painting, I was giving it a voice-and by giving it a voice, I was waking it up to scream across the front page of the world.

OW: What did you spray-paint on the painting?

TS: The words Kill Lies All. The idea had come in response to James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake-the phrase “Lies. All lies.” taken from that book and altered with the word kill. I was doing a lot of reading of philosophy and literature at the time. I wasn’t the only one-many people were doing things like that with language, putting common words or phrases in the context of art as a way to communicate.

OW: When you run up against people who maybe don’t have the sensitivity for that explanation of why you did what you did, and who just consider it somebody defacing one of the most important pieces of art of the 20th century, are you sympathetic to that?

TS: No, not at all. Firstly, my thing wasn’t about defacing it at all. For me, it was a matter of doing something and naïvely thinking-idealistically and in a way that was very rhetorical and language-

orientated-that the purpose was for the good of art, to enhance it and bring it to the world’s attention. My intention was to put that painting on the front page of The New York Times and of every other newspaper in the world-and that did happen. So it wasn’t a hit-and-run, cowardly prank. The critical factor is to realize that the burning, the rage, the inhumanity, and the hatred that is rampant in American culture was really coming to the surface. In a climate like that, nobody pays attention to pretty paintings. The role of art was, I felt, very important and being neglected. So that’s what led to that point.

OW: You know, I’ve always admired the sculptures you did as an artist back in London in the ’60s, but you’ve always seemed kind of shy about them. Do you see yourself more as an artist or as an art dealer?

TS: I think professionally what I do is run a gallery and represent some of the art of our time.

OW: But do you think of yourself as an artist who happens to run a gallery?

TS: I don’t know what to say. I was asked in 1969 by Lucy Lippard to define art. I think at the time I said that art was a matter of life and death, meaning just the breathing and living and thinking experience-that’s what art is. I like what Rauschenberg told me late in life: “Do you think I chose to be me?”

OW: But do you ever feel guilty that you haven’t spent more time pursuing your own art? Or do you feel that your mission is to represent other artists?

TS: It’s not that I feel guilty-I don’t. I just think that the whole experience of living, breathing, thinking, and being lost in wonderment is, for me, that of being an artist. And the idea of identifying as someone who is just living and existing and making objects or paintings-somehow I moved away from that years and years ago.

OW: William Faulkner once said that “the writer’s only responsibility is to his art.” Do you think that applies to art and artists?

TS: Well, I don’t think there’s one responsibility that’s an umbrella and applies to every artist. I think, firstly, an artist’s responsibility is to realize-

OW: Hold on. Just let me get this down . . . disagrees with William Faulkner. Okay, got it. Go ahead.

TS: What? [laughs] I don’t disagree with Faulkner at all, no. I think that the first responsibility of an artist is to follow truth, and the innate original forces and energies that are within them. At the same time, I also think, collectively, that there has to be a place for artists to reflect and deal with the society they’re living in. I think that great art inevitably reflects some of the drama and trauma and conflicts that exist in the outer world.

OW: What do you think your responsibility is as a gallery owner?

TS: To fulfill whatever it is that I started many years ago, the discoveries that I’ve made. And then also to make significant, meaningful exhibitions. It’s really about getting through the day with some meaningful advancement, as well as maybe making some business happen, of course.

OW: Where do you think art is right now?

TS: Well, all in all, I’m happy that the evolution of art in the past 25 years, and the place of art in global culture-and even finance-has gotten to be so important. One thing I’m really proud of is the fact that now anybody can do anything. The work can be small or large, painting or sculpture, whatever it might be-it’s all viable, and it can come from any part of the world. So the idea of democracy has really taken hold. Right now, as an investment, art has become a huge phenomenon, and prices have risen to astronomical levels. The volume of art produced has also grown to be so great, and all of that comes as a reflection of a much broader interest. I just wish that with the increase in prices and in the amount of art that’s made, there would also come an increased interest in the questions that art asks and in the perpetual state of questioning that should be within it. This is, in a way, a continuation of the spirit that was involved in my spray-painting of Guernica. It’s not at all about destruction. It’s about the preservation of the truth and the place of honor, respect, and dignity that is all wrapped up in the singular act of appreciation.