designer

The Patient Persistence, and the Payoff, of Being Peter Do

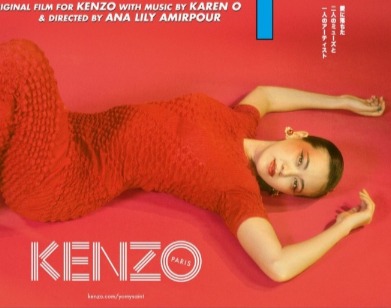

Just three years ago Kenzo became the first fashion house to present at Paris Fashion Week without a single white model. The label’s Spring/ Summer 2018 runway show, which boasted a staggering 83 models from across the Asian diaspora, was the brainchild of Humberto Leon and Carol Lim, the dynamic creative directors who resuscitated the waning brand after their storied tenure as founders of the disruptive downtown favorite Opening Ceremony. Watching the presentation was a young Peter Do, who at the time was working as a junior designer at Celine. While at the iconic atelier, Do, who grew up on a small farm in Vietnam before moving to Philadelphia as a teenager, often wandered past Kenzo’s double doors a few steps down the Rue Vivienne, hoping to catch a glimpse of Leon and Lim. In an industry marked by racial homogeneity, the pair had forged a path for irreverent, exuberant Asian creatives hoping to reshape fashion from its very epicenter. As he watched the duo greet the applauding crowd after the show, Do knew it was time for him to join their ranks.

The following year, Do was back at Paris Fashion Week, this time as the founder of his eponymous label. With no business acumen or sales plan, the 29-year-old designer presented his Spring/Summer 2019 collection, a line of exquisitely tailored, airy dresses and trench coats, out of the apartment of a distant acquaintance. From this improvised chaos emerged recognition: Over four collections characterized by innovative minimalism, the designer and his team have captured the imagination of an industry hungry for authenticity. Do’s conviction that clothes should be made to last reflects a childhood spent breathing new life, year after year, into a modest wardrobe of five garments. And though his designs are a testament to traditions of uncompromising workmanship and expertise, as he tells Lim and Leon, sometimes the best way forward is having no clue what comes next. —MARA VEITCH

———

PETER DO: It’s a huge honor to be talking to you both. I remember your summer 2018 show vividly, watching one Asian model after the next come out. I was like, “Okay, when’s this going to stop?” But it was the whole show. I didn’t think that was possible at the time, and I felt very represented and proud.

HUMBERTO LEON: That was a really important show for us, too. When we started at Kenzo in 2011, the industry was very different. We got a lot of criticism early on for staging those elaborate shows with all-encompassing casting, but Carol and I always kept in mind that Kenzo was really the first to do a lot of things. There weren’t many other gay Asians in Paris fashion, or fashion in general, when he started out. Aside from the clothing and the visuals, I’m proud that we never wasted an opportunity to celebrate our Asianness at Kenzo, and it was oddly a really big deal to people. When we got to Paris, every interviewer was like, “You’re the first Asians to take over a brand.” We felt the pressure to really deliver. I, too, had never seen a show with an all-Asian cast before ours, at least not in the West. Believe it or not, it was very difficult to put together. We had 83 models, which is a huge cast for a show regardless of ethnicity. Before everyone even came on stage, Carol and I and all the models were crying backstage. That feeling of acceptance, of non-objectification, was special for us.

CAROL LIM: One of the other things about Kenzo was that he managed to achieve longevity in Paris, one of the most difficult cities to gain a foothold in. He was not just seen as Asian—he created a global brand and it just so happened that he was Asian. In a way, that’s even more powerful, because he showed that we’re not just regional designers.

DO: Exactly. I grew up on a small farm in Vietnam, and I never dreamed that this is what I would grow up to do. It’s beyond what I could even imagine. We get DMs every day on Instagram from kids with similar backgrounds who want to know what my story is and how I managed to get here. I want them to know that it was not a fairy tale; it’s grounded in many realities and hardships—but they can do it, too.

LEON: I think you should translate this conversation into Vietnamese and post it on your social media so that the young version of you in Vietnam, who might not read English, can see it.

DO: I love that. Maybe I’ll ask my brother to do it; he’s a better translator than I am. I’m definitely going to call my mom when it comes out and read it to her.

LEON: Can she understand English?

DO: Yeah, she works at a nail salon, so she knows enough to have a conversation.

LEON: What was your family life like in Vietnam? What got you into fashion?

DO: I had a very humble, but happy childhood. I grew up in nature. I lived with my grandmother and younger brother outside the city, and spent my days playing and feeding the chickens. In Vietnam, you don’t go shopping. I owned a maximum of five pieces of clothing as a child. I had my uniform: a white shirt and black pants, one pair of overalls, shorts, and a t-shirt. When you’ve worn your clothes to death, you patch them up or you get your cousin’s hand-me-downs. That mentality always stayed with me, even when I moved to the U.S. at 14. The first time I went shopping was at a mall in Philadelphia, and after that I watched a lot of YouTube videos about fashion and dreamed about creating garments. But I didn’t really understand fashion with a capital “F” until I left college and got a job working under Phoebe [Philo, the former creative director at Celine].

LEON: How long did you live apart from your parents?

DO: We were apart ten years. They left Vietnam to support us, and I moved to the U.S. to be with them.

LEON: Was there ever a moment growing up when you realized, “I’m fascinated by that piece of clothing?”

DO: No, honestly. There wasn’t a moment where I thought about clothing beyond its functionality. My grandma taught me how to patch holes and re-sew buttons, because nothing was replaced. It wasn’t until I came to America that I felt like my clothes could be used to express who I am.

LIM: So, at 14, you arrived in a new country and also kind of met your parents for the first time. What were your coping mechanisms?

DO: It was very lonely not speaking the language, and I was bullied a lot. The first time I was bullied because of what I was wearing left a really strong impression on me. I realized instantly that I was an outsider, which was a new feeling, because in Vietnam everyone was similar. Bullying was a part of that first interaction with diversity and different cultures. I remember thinking, “I need to buy new clothes.” I knew that I had to do something to start this new chapter.

LEON: Can you describe what your look was before, and what that transformation was like?

DO: At the time in Vietnam, we were wearing a lot of tight graphic shirts, flared jeans, and flip-flops. It was very ’70s. A week after I arrived, I was wearing Abercrombie & Fitch and Hollister. All I wanted was to be cool and make friends. I remember sneaking to the mall in high school to buy black, ripped skinny jeans at Hot Topic. I never ended up wearing them out of the house—I just hid them underneath my other clothes and wore them around my room at night. They were an escape from my shell of, like, A-plus Asian student.

LEON: Who were the first people you felt at home with when you got to the U.S.?

DO: My first friend was Andrew, who was from Albania. Neither of us really spoke English, so we ate lunch together in silence. We were just happy not to feel so alone. I still have nightmares about lunch in high school, eating in the bathroom by myself. There were so many nuances in English that my textbooks hadn’t taught me. People would say, “’Sup,” and I was like, “Does that mean ‘How are you?’”

LEON: What aspects of American fashion stood out to you? How did you realize you wanted to study design?

DO: I was in charge of an arts club in my high school, and during my senior year we decided to host a fashion show for our yearly fundraiser. At that time, Project Runway was all the rage in the suburbs, and so was sustainability. My mom bought me a sewing machine from Kmart for $20, and we sat at the kitchen table all night learning how to thread it. We really bonded over that. I made ten looks over the next three months from trash bags full of donated clothes. After the show, I realized I needed to switch my intended major from architecture to fashion design. I didn’t tell my mom that I’d done it until she dropped me off on campus in Brooklyn that summer.

LIM: When you came to New York, did you have a plan? How did you get started?

DO: I never had a plan. I was always very naive. I spent a lot of time in my apartment, just making things and documenting my process on Tumblr. It was a very personal journey in a way, because I didn’t know anything about the industry. I just wanted to create. I interned a lot, and I learned about the Garment District by running around picking up zippers and swatches. I wasn’t as interested in the business side of fashion until after I started a brand.

LEON: I think it’s important to be naive about some things, because it gives you room to do things your own way. When you’re taught too much, you start to follow these rhythms of how things should be done. When Carol and I first started Opening Ceremony, we’d never had a store. We’d never made clothes. We never did wholesale. Every time somebody wanted to buy our clothes, Carol and I were like, “How do we do this?”

DO: How did you guys feel when you started? What did you think that Opening Ceremony could offer people?

LEON: Carol and I were massive shoppers. That was basically our pastime. We had our go-to spots, but there weren’t places in New York that were perfect for us. There was a lot of cool and there was a lot of fancy, but there was nothing attainable and weird. Then we went to visit friends in Hong Kong, and there were no preconceived ideas about high and low fashion. The fashion landscape was just pure. We wanted Opening Ceremony to be a place where you could shop without worrying about judgment or price point. In our first month, everything in the store sold out. We called all of our friends and forced them to work a shift so that we could go buying in Hong Kong for a week. Later on, we started making the clothes that we felt were missing. That’s when places like Barneys started coming around.

DO: I’ve heard enough stories to be wary of growing too much too fast. That’s why I’m just enjoying every accomplishment as it comes, and I try not to let things go unnoticed. I don’t want to look back years from now and be like, “That five-year blur, that was the journey.” I want to remember every step. In the beginning, we had no money and no idea where to start. My designer and I knocked on every single factory door in New York and literally begged people to work with us. We started with one sewing machine and now we have four. We’ve gone from 5 members to 12, but we still have the same iron that we started with.

LEON: Hearing you say that makes me want to ask about your mom. You mentioned that you were afraid to tell her you were studying fashion. Was there a moment when she finally came around?

DO: With every milestone, she accepts my career a little bit more. When I called her and said, “Oh my god, I won the LVMH Graduates Prize,” she was like, “Does that come with money?” When I told her I was going to Celine, she asked, “You mean Chanel?” But even though she didn’t approve, she was there every step of the way. I made no money when I worked at Celine, and I remember calling her crying when I couldn’t pay rent. It was hard for her to go through that with me for so long. But I was at Derek Lam around the time that people in Vietnam had begun noticing homegrown talent. Then my mom started saying, “Oh my god, they know about you in Vietnam.” I think it’s kind of hit her now that I’m doing something that’s relevant.

LEON: Does she own any Peter Do?

DO: She does. Every season I send her a selection of what I think she would like. She calls and says, “I love this skirt. I can wear it to church.”

LEON: I want to see her in a Peter Do lookbook.

DO: I should ask her. I know she would do it, but she’s very shy. That reminds me, I want to talk about being Asian in Paris. When I moved there to work at Celine, I knew right away that I was an outsider. Every Asian is an intern or a cutter, and the senior people are all very old-fashioned and French. I remember thinking about you guys next door, the heads of a top French house, so far beyond this wall that I was facing. It gave me a lot of hope.

LEON: We felt a big responsibility from the beginning about what we needed to bring to our role as Asians working for an Asian-founded house. I mean, we’re also New Yorkers and we tried to bring a bit of what we knew from that world, too—throwing monthly parties and massive karaoke nights. I think most Asians who work or travel in Europe realize the subtle racism that happens there. It’s not all ill-intentioned, but a lot of it is ill-informed. That motivated us to recruit one of the most inclusive groups of people in fashion at that time at Kenzo.

LIM: We hired the best people, but we weren’t afraid to say, “Well, we want some people from New York, and some from Asia.” We know exactly the joy of where you are right now with your brand, because you do everything—you touch every single piece and you know every single team member. When we got to Kenzo, we did that. We were like, “We’re going to do this differently. Everyone’s going to sit together, and we’re all going to have breakfast together.” Everyone was like, “What is going on? We don’t eat this way.” But that’s just who we were. We brought our culture, our life, our approach, and our family from Opening Ceremony to Kenzo, because we could.

DO: At so many companies, you go through this hazing. I always told myself that if I had the chance to run my own company, I would never allow some of the things I’ve seen happen before. I believe that if you let that culture happen, it trickles down. I’m very proud that everyone at Peter Do treats each other with such kindness. It radiates outward from the way we handle our factories to our interactions with buyers.

LEON: Yeah, the hierarchy just feels so old. I hate to say it, but young people have more interesting ideas. If you work somewhere for 10 or 15 years, it can be hard to come up with something new. In order for me and Carol to feel like we’re moving forward, we always have to feel slightly uncomfortable about the situation we’re in. Can you relate to that?

DO: Yeah. We start every collection with a list of things that we hate. I hate lace so much, so we started one collection by looking at lace. I hate the color purple. Now we’re doing purple this season. Taste is relative, right?

LEON: [Laughs] Right.

DO: It’s uncomfortable to admit, but a lot of the time I don’t have all the answers, and I’ve had to tell my team that, too. I don’t always know what direction we’re headed, but that’s okay. We can watch a movie together, we can look for inspiration together, we can share a meal together. We can figure it out.

———

Model: Anh Duong at IMG.

Hair: Eric Williams at Streeters using Bumble and Bumble

Makeup: Jamal Scott at The Teknique Group

Casting: By Margeaux

Prop Stylist: Jacob Burstein

Manicure: Aja Walton at See Management using Essie

Photography Assistants: James Bee and Kristina Dittmar

Fashion Assistant: Caroline Gillen

Post-Production: Ink

Special Thanks: Picturehouse/ The Small Darkroom