Polly Mellen

In a career that spanned more than half a century, Polly Mellen helped create some of the most indelible imagery in the history of fashion. Her work as a stylist and editor, first under the legendary Diana Vreeland at Harper’s Bazaar, and later under both Vreeland and Grace Mirabella at Vogue, helped define a new, more modern ethos about clothes and how women wore them. With an almost playful daring, it brimmed with a kind of strong, smart, unabashedly celebratory feminine independence—as well as an artful element of provocation and extravagance—that Mellen herself embodied and drew upon in her collaborations with photographers such as Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Irving Penn, and later Steven Meisel (who took the pictures that accompany this story), Mario Testino, Patrick Demarchelier, and Steven Klein. In Avedon, in particular, she found a lifelong fashion-world partner-in-crime. When the late photographer was first introduced to her, he didn’t want to work with her because he thought she was “too noisy.” But the spectacular and wide-ranging body of images they ended up producing together—including iconic pictures of up-and-coming models such as Penelope Tree, Patti Hansen, and Lauren Hutton, and their now-famous 1981 nude of actress Nastassja Kinski wearing nothing save an ivory Patricia von Musulin bracelet and elegantly wrapped by a boa constrictor—is not only a testament to the kind of creative chemistry they had, but also to their ability to visually and innovatively capture something singular about fashion, people, politics, history, and the white-lightning essence of a moment in their work.

Born Polly Allen in West Hartford, Connecticut, Mellen attended Miss Porter’s School for girls and later worked as a nurse’s aid during the end of the Second World War, before following her older sister, Nancy, to New York City, where Mellen got a job as a salesgirl at the department store Lord & Taylor. In 1950, Mellen was hired as a fashion editor at Mademoiselle. Soon after, a friend from Mellen’s Lord & Taylor days arranged a meeting with Vreeland, the fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar, which, under the stewardship of longtime editor Carmel Snow and art director Alexey Brodovich, had become the magazine on the creative cutting edge of fashion in America. Vreeland hired Mellen, introduced her to Avedon, and later brought both of them with her to Vogue, where Vreeland served as editor in chief for six years before giving way to Mirabella—and where Mellen blossomed, and her almost gleeful passion and enthusiasm for ferreting out new designers, discovering new talent, and creating new images helped fuel the magazine’s fashion coverage for more than three decades.

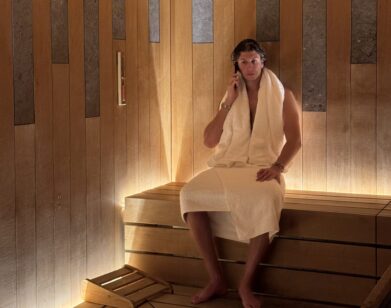

After leaving Vogue in the early ’90s, Mellen served as creative director at Allure for eight years before retiring in 2001 to her country home in South Kent, Connecticut, with her husband of 45 years, Henry Mellen. Now 86, she spends much of her time reveling in the role of mother to her four grown children and grandmother to her five grandchildren—though her life is also filled with a robust physical regimen that includes a steady diet of golf, Pilates, skiing (she prefers downhill), swimming, and gardening. And, of course, she still follows fashion, and can occasionally be spotted at certain very select New York shows—such as the Fall/Winter 2010 runway presentation put on last February by her former assistant, Vera Wang—applauding in her signature style, with her hands thrust high in the air above her head.

Balenciaga designer Nicolas Ghesquière, of whose work Mellen was an early champion—and who recalls first encountering Mellen in the early ’90s while he was an intern for Jean Paul Gaultier—recently reconnected with her from Paris.

THE SNAKE WOUND UP HER LITTLE NAKED BODY AND PUT ITS TONGUE IN HER EAR AND THE PICTURE WAS DONE. I COULDN’T BELIEVE WHAT I WAS SEEING. I LOVED IT. I HELD IT. HAVE YOU EVER HELD A SNAKE? IT IS SO EROTIC.Polly Mellen

NICOLAS GHESQUIÈRE: I wanted to start by asking you something very simple: You are often referred to as one of the chicest women in the world. So what are you wearing right now, Polly?

POLLY MELLEN: Well, I’m wearing my black pants that have three white stripes down the side. I got them at an athletic store. And then I have a white T-shirt, and over that I have a black-and-white striped long-sleeved cardigan. And then I have bare feet. The pants that I’m wearing are Adidas, if that matters.

GHESQUIÈRE: [laughs] That sounds perfect. Where are you?

MELLEN: At our house in Connecticut. It used to be an apple barn. It had dirt floors and everything else, so we restored it. It took us almost two years. We live very high up at the foot of the hills. And we have a lovely garden—mostly a perennial garden that is all shades of green. We don’t have as many annuals because I love things that keep coming up year after year. I love bushes and trees and things of that sort. We have a lovely lawn—a big lawn—and a very delicious swimming pool, which is a free-form pool.

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s great. I’m happy to be able to visualize the situation.

MELLEN: Our house is a very simple house. It’s in a town called South Kent, Connecticut. We had this house for a while, but when the time came for us to move out of New York City, when we made that decision, we decided to add on to it and live here permanently. We just love it.

GHESQUIÈRE: This is where you’re from, Connecticut.

MELLEN: Yes. I’m from a town called West Hartford. I was born and raised there.

GHESQUIÈRE: Can I ask you to describe your upbringing a little bit for me? What was your family like? Your parents were not in fashion.

MELLEN: No, no, no. But they were enormously chic. My father was very chic. My mother was a heavy woman and she wore wonderful, bright colors, and pajamas, but when she was in town or in New York City or in Paris, she would wear navy blue or black. But there was a

flamboyance to both of them. I had four siblings—three sisters and a brother. My brother is no longer alive and my eldest sister is no longer alive, but my two other sisters are alive and we’re all very, very close. We were brought up beautifully, Nicolas—a very happy family.

GHESQUIÈRE: Well, that sets you up for the rest of your life.

MELLEN: Absolutely. It gives you a brick-by-brick foundation that you build on for the rest of your life. And then it teaches you so many things that are important in your life, like being a good sport, and not thinking negatively, and always having a good feeling for your fellow man. We went to wonderful schools. We just had a great life and I’m ever grateful for it.

GHESQUIÈRE: I think what you’re saying about having positive energy and the things you learned from your education—I think that’s what you gave to fashion for so many years. How did your interest in fashion begin? In French we have this word déclic. It’s when you have, suddenly, a light shining and you say, “This is what I want to do.” What was the click for you?

MELLEN: Well, when I was very young—I think I was about 4 . . .

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s very, very young . . . [laughs]

MELLEN: But I always took a great interest in my clothes. My sister, who was 13 months older, and I always dressed alike, but as I got a little bit older, I didn’t like that because I wanted to dress differently. So our mother would put Patty in blue and Polly in pink, or we would wear complementary colors, but the shapes we were wearing were always the same, and I was very interested in that. I also took great interest in my dolls and their clothes. My mother sewed different things for our dolls to wear. She was always so thrilled to see what we were putting on our dolls and how we were putting together the different combinations of clothes and the whole bit of it. I think that’s what started it.

GHESQUIÈRE: So you became interested in fashion really by the way you were dressed as a child and by playing with fabrics and colors, with your toys and your dolls, and being surrounded by inspiring things.

MELLEN: I think movies also played a part. I’ve also always been hooked on the movies. From my early teens on, I always had my favorite movie stars who I admired, like Carole Lombard and Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, and the men in my life who I loved, like Gary Cooper. I thought Fred Astaire was the most chic man. I loved the way he dressed. Never mind his dancing, which was beyond—he was just so elegant and had this freedom of body. I also had a huge crush on William Holden. I would go to see William Holden’s movies alone—I didn’t want to be with anybody. I just wanted to be with him.

I DO OCCASIONALLY FEEL A GREAT DISAPPOINTMENT IN SOME OF THE THINGS THAT I SEE FROM CERTAIN PEOPLE. BUT IT IS TODAY. YOU CANNOT SQUELCH WHAT’S HAPPENING AT THE MOMENT—YOU CANNOT PUT A LID ON IT AND SQUASH IT DOWN.Polly Mellen

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s very romantic.

MELLEN: It was so romantic. I also loved the masculine style of dressing of Katharine Hepburn, who came from the same town that I came from. I was fascinated by the way she wore trousers. So I think the romanticism of the movies also influenced my life and my interest in fashion greatly.

GHESQUIÈRE: So how did you then take steps to become part of this world of fashion?

MELLEN: When I graduated from school, World War II was still going on. At the time, my eldest sister, Nancy, was working in New York City at Lord & Taylor, and she had a great friend named Sally Kirkland who she worked with there and who later went to work as an editor at Vogue. I always told them, “I want to work in fashion like you do,” and finally, in the late ’40s, I got a job at Lord & Taylor, too. Eventually, Sally Kirkland left Lord & Taylor to go work at Vogue, and I got a job at Mademoiselle. So one day, Sally said to Diana Vreeland, who was the fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar at the time, “I have a young woman I want you to meet. She’s very young, but I think you should meet her.” When Sally Kirkland told me this, I said, “I can’t possibly do that! I’m going to throw up! That’s the scariest thing I’ve ever heard! I can’t do that, Sally. I’m not ready to do that!” But Sally said, “You let them make that decision.” So she set up an appointment for me with Mrs. Vreeland, and it all started from there.

GHESQUIÈRE: What was that like, your first meeting with Mrs. Vreeland? What was she like?

MELLEN: Well, I was in total awe of her. Because I was working at Mademoiselle I had seen her, but I was absolutely terrified. I went up to the floor where her office was, and I was sitting in a little chair waiting to be called and hoping I wasn’t going to be sick to my stomach with nerves. Eventually her secretary came out and said, “Polly Allen? Mrs. Vreeland is ready to see you.” And I walked into Mrs. Vreeland’s office and the girl closed the door and we were alone together for about 40 minutes. Mrs. Vreeland was wearing Mainbocher—a grey flannel skirt, a grey turtleneck sweater, and her hair was always—

GHESQUIÈRE: Pulled up in the back?

MELLEN: Lacquered, sort of. It was navy blue, her hair. And over that she wore a netting, and a black a bow that she’d tied. She had very dark red lips, and wonderful rouged cheeks, and around her neck, medallions of gold and chains. I have no idea what I had on. No idea. All I know is that she put me at ease instantly. She later told me that she did that because she wanted to erase any nerves in me so that she could really get to me, and hear what I was feeling in my heart—what my feelings were about fashion and why I wanted to come to work at Harper’s Bazaar. But because she erased that fear inside me, Nicolas, I was able to let go. And evidently, I really did let go.

GHESQUIÈRE: I think you must have. [both laugh]

MELLEN: I think she recognized the passion and the energy I had. I stayed at Harper’s Bazaar for two years, until I met my first husband and moved on to Philadelphia in 1952. But they were incredible years—wonderful, wonderful years. But, anyway, my career sort of took off from there. I was really blessed.

GHESQUIÈRE: But you were also talented.

MELLEN: Well, I was surrounded by talented people. I always remember Mrs. [Carmel] Snow [the editor of Harper’s Bazaar from 1934 to 1958] saying to me, “You know, Polly, if one person thinks they’re a big star, then we’re all stars. You just go out there and always do your best. And always have time to see any designer—no matter how big or how small, have time to see them. You don’t have to just see the big shots. You never know what’s coming around the corner and the talent that is going to be important. That is your job.”

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s the best advice.

MELLEN: It’s great advice—to open your eyes, have a little humility, and let go of ego. I think that instills in you a sense of responsibility. I also think you have to feel like you want to enrich your life, and you want to keep your eyes open, and you want to listen and be a good listener. And you have to want to dare, Nicolas. You have to dare or you don’t go that step further. You have to be willing to stretch—and to not only be willing to stretch, but to want to stretch.

GHESQUIÈRE: The want is important.

MELLEN: Yes. It’s the hunger.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you recall your first memorable shoot? Is there one early one that stands out from the others?

MELLEN: Well, when I got to Bazaar I wanted to work with Dick Avedon, but he didn’t want to work with me. He told Mrs. Vreeland that I was too noisy.

GHESQUIÈRE: [laughs] I know! I read that. This is insane!

MELLEN: But we did end up working together. My first shoot with him was with Audrey Hepburn. She wore a yellow, foiled, bouffant dress with white stripes. So I walked in and did the shoot with her and with Dick, and I never spoke—or if I spoke, I spoke in a very small way. But at the same time, Dick told me that when she would get into position, I should always run in and fix something—to make it more extravagant maybe. At first, though, I wouldn’t move, because I didn’t want to get in his way. But Dick said that he could sense my energy and my wanting to do something to make the picture better.

GHESQUIÈRE: Without saying a word.

MELLEN: Without saying a word. So it’s very funny that he became my best friend in the fashion world.

GHESQUIÈRE: What is a friend in fashion?

MELLEN: Somebody who believes in you and lets you take things further. I think that with any shoot that Dick and I ever did together, that was the case. After he went to Vogue and they called me and asked me to come over, too, our first shoot together involved a five-week trip to the Orient.

GHESQUIÈRE: Wow.

MELLEN: You cannot imagine what an influence that had on me. I mean, the culture, the absorption of the Japanese way of life, the Japanese way of thinking, the discipline . . . the gardens! Even the poorest people would wrap their little trees in gauze—it looked like gauze, but

of course it wasn’t. It was burlap or something.

GHESQUIÈRE: To cover them during winter. To protect them, right?

MELLEN: Yes. But the entire thing was an extraordinary experience. So these were more than memorable things to me. That’s why you have to keep your mind open—so that you can be given the privilege to have five weeks in Japan and take all of that in. I mean, that’s privilege to be able to do that. And you have to give that privilege back—it doesn’t belong to you. It belongs to the madding crowd.

YOU HAVE TO MOVE FORWARD. THEY’RE WONDERFUL, THE ACCOLADES, AND YOU APPRECIATE THEM. BUT THEN YOU GO ON TO THE NEXT MOMENT. YOU HAVE TO ALWAYS BE GOING OUT TO THE END OF THE DIVING BOARD AND DIVING OFF. Polly Mellen

GHESQUIÈRE: What was Mrs. Vreeland’s relationship like with Dick Avedon? She knew what she wanted, I’m sure, but what was the process when the three of you were working together on shoots?

MELLEN: Well, she would always come to the shoot in the beginning and she would start out by listening. She would make me talk to her about what we were going to do, because she wanted to hear where I was coming from. For example, let’s say Dick was going to photograph somebody—a beautiful girl like Suzy Parker. And say, if we were doing Suzy Parker, then we’d do some wonderful coats or dresses. Mrs. Vreeland would start by wanting me to speak to her about how I saw the shoot. And then I would go speak with Dick and explain it to him, and show him the clothes that Mrs. Vreeland and I had chosen together, and we would take it from there. I remember once I didn’t like a dress that we had to shoot—I’ll never forget this—and so I turned it inside out and put it on the model backward.

GHESQUIÈRE: Oh, my god! [laughs]

MELLEN: Then I took a man’s leather belt and cinched the waist as tiny as I could get it. I almost lost my job for doing that because the designer of the dress was an advertiser. Mrs. Snow called me in and said, “Don’t you ever do that again!” But I thought it looked great inside out. [laughs]

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes. It sounds like a Japanese deconstruction before that even existed!

MELLEN: But that was the beginning of the business, Nicolas.

GHESQUIÈRE: I think, in your work with Avedon, you invented a new kind of fashion picture.

MELLEN: Starting with Nastassja Kinski.

GHESQUIÈRE: Exactly.

MELLEN: No clothes. I wish I hadn’t even put that bracelet on her.

GHESQUIÈRE: [laughs] Now today you want to take off the bracelet? I love that! I think that image you made with Avedon was one of the most remarkable ever.

MELLEN: You couldn’t imagine being there. I mean, the snake kissed her! The snake wound up her little naked body and put its tongue in her ear, and the picture was done. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The snake had been defanged, so there was no worry on that stance.

GHESQUIÈRE: But it was a big snake! It was not small.

MELLEN: I loved it. I held it, which was a very erotic feeling. Have you ever held a snake? Well, let me tell you, it is so erotic.

GHESQUIÈRE: I know, very erotic and very provocative. I wanted to ask you: That sort of imagery used to be erotic, but also very elegant and chic. Today, though, it seems like that kind of imagery has turned into something more vulgar in fashion photography. What is your point of view on that?

MELLEN: I want to tell you that I personally do not think that I have ever done, in my working life, anything vulgar. I know I’ve done provocative things. But vulgar? No. Sometimes, though, I’ve seen some visual things that I do think are vulgar . . .

GHESQUIÈRE: Today.

MELLEN: Yes, today. And I think the reason for that is because of the freedom that there is now to do certain things, and a lack of sophistication on the part of some people who, in their work, like to give the impression of, “Has there been intercourse or not? Are they about to?” But they take it into a realm that has a vulgar touch to it. I can think of a lot of things right now as I’m sitting here, but I don’t feel like I should speak about them, because I think that wouldn’t be right. One day if we’re alone I’ll use names, because stories are always much more fun when you use names, but I can’t do that now, because I would get in trouble—and I have gotten into trouble. [laughs]

GHESQUIÈRE: What’s your feeling about fashion today in general? Let’s start with the images. What do you think of the fashion photography we are seeing now? I mean, you worked with Avedon, Irving Penn, Helmut Newton—so many of the greats.

MELLEN: Working with those photographers was wonderful. It was very hard work, but you wouldn’t even think about hard work because you were so entranced. I think there a lot of great photographers working right now. For example, I think that Steven Klein, who I’ve worked with, is incredibly talented. At the same time I do occasionally feel a great disappointment in some of the things that I see from certain people. But it is today, Nicolas.

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes, it is today.

MELLEN: You cannot squelch what’s happening at the moment—you cannot put a lid on it and squash it down.

GHESQUIÈRE: You’ve worked a lot with Steven Meisel, who is another incredible talent. What is that relationship like?

MELLEN: Wonderful—just terrific. Steven is completely consumed with what interests him. He does what he wants to do, and when something doesn’t interest him, he’s not afraid to say so. I think that’s why you don’t see his work all over the place as often as you might like to. Today he only photographs what he wants to photograph, what turns him on. He has an extraordinary eye, and his sophistication is limitless. This is a man who doesn’t miss a beat. So there are some very creative people out there who are like that, and that is why their work is so extraordinary.

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes, and these people are looking forward too—they always have a vision.

MELLEN: I mean, I will never get tired of looking at works by Picasso. I will never get tired of looking at work by Francis Bacon or Henry Moore or Francisco Goya. You cannot tire of the work these people have made because you can look it over and over again—the same thing—and always see something different.

GHESQUIÈRE: You rediscover it every time.

MELLEN: Absolutely. You can squint and see something else, or something will come forward in the paint. You’ll always see something else.

GHESQUIÈRE: What about in terms of designers? What do you think about what’s going on right now?

MELLEN: Well, I think that some people have wonderful spots right now. I think that Karl Lagerfeld has a wonderful spot designing for Chanel. They really just let him go. I think John Galliano is a huge talent. Marc Jacobs is also a huge talent—and a very interesting one to me. I think Alexander McQueen was very, very special. When I went to his first show, I couldn’t speak because I was so enthralled. I was saying to myself, “What am I looking at here? What’s going on here?” Because, Nicolas, I’m really a loner. I’ve been a loner for a long time, because I guess I prefer that. For me to get the best out of myself, I have to trust my judgment. And so while watching an Alexander McQueen collection, I would feel isolated. Even though I was surrounded, I would still feel isolated by what I was looking at, if that makes sense.

GHESQUIÈRE: Yeah, absolutely. It’s like what you are seeing is taking you to a place where no one can be with you. I think what we’re talking about is a sense of fashion as laboratory work. I mean, we are not scientific, of course, but we are looking for ideas all the time. I think creating the clothes is about creating historical images—and that’s about more than fashion. It is about the fashion, the photography, what you are doing in the moment. It’s what we call in French rechercher, or the search for that thing. So even though fashion is not scientific, I think being a designer is somewhat like being a scientist.

MELLEN: That’s why I never miss one of your collections, Nicolas. I look at your clothes and I see within them the interest in color, in fabric, in shape.

GHESQUIÈRE: Well, thank you. I am lucky also because Balenciaga is such an amazing inspiration.

MELLEN: Well, there is no question about that. But also, when you think about [Balenciaga muse and model] Charlotte Gainsbourg and Lou Doillon—I mean, you look at their mother [Jane Birkin], and what they have grown up to be . . . They aren’t invaded in fashion, and yet they love it.

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes, absolutely. And I love the fact that they never carry couture.

MELLEN: Totally. I mean, who is going to schlep these big skirts and trains and all these things? How wonderful it is to see the young in miniskirts!

GHESQUIÈRE: You know, there is something I think we share, which is, of course, an appreciation for Helmut Lang. I think at a certain point he really changed so many things in fashion. I’m a bit younger than Helmut, but from my point of view he provided a true entrance into this new way of thinking.

MELLEN: He is an amazing man—always striving, always moving forward. I have all my Helmut Lang.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you still wear your Helmut?

MELLEN: Oh, yes. I wear all my T-shirts with the holes in the elbows, which people always speak of. When my husband gets a hole in his sweater, at his elbow, he says, “It’s very Helmut Lang!” [both laugh]

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you think fashion is too nostalgic today?

MELLEN: Oh, Nicolas, not your fashion. [Ghesquière laughs] But I do think there is a lack of modernity at the moment—and I don’t even like that word, modernity, anymore. There aren’t enough designers today anyway—there are more stylists. And then there are certain people who hang onto nostalgia and I wish they wouldn’t. I wish the young beautiful actresses and other people—I wish they would not hark back to clothes that look more like they’ve dressed in their mother’s clothes. You know, I’m out of it, but I’m also in it, Nicolas, if you know what I mean.

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s interesting to me, too, now how closely the fashion editors work with the designers. I mean, you used to do that in a little bit of a different way. You were very supportive of people like Calvin Klein and Halston [Roy Halston Frowick] and Geoffrey Beene. But today it’s a big business, where all of these editors are consultants for brands. I don’t know if that’s new, but it has become very official over the past 25 or 30 years—and today it’s probably at its most extreme point, where sometimes collections look more like a stylist’s work than a designer’s signature.

MELLEN: That’s right. That bothers me when I see that. It tells me that the designer has lost sight of what he or she really wants to do, and that he or she is listening to the strength of a very strong stylist and being a little watered down—and by watered down, I mean, the strength of the designer’s vision. I’m not saying it’s easy, Nicolas.

GHESQUIÈRE: No, it’s not.

MELLEN: It’s not easy. But if you’ve taken the job to be the stylist for a collection, then I think it’s important for you to really listen to the designer and look at the board. Look at the wall, look at what the designer is interested in, and then move on to that. But the designer also must not lose sight of the reason for their point of view. Otherwise it won’t come across. I went to Vera Wang’s collection this year, her last one, and I loved it. It was all black—different shades of black—and, well, I love black.

GHESQUIÈRE: [laughs] We know that!

MELLEN: Yeah. But I love color too! In any case, because I know Vera so well, I know that she wouldn’t mind my saying this, but it was suggested to her at one point that she add more color to the collection and she didn’t do it. Now that takes guts—and I like people with guts. I want to feel in the clothes what the designer is really feeling when they’re alone with themselves and their fabrics and they’re drawings, and what happens when they let the creativity that they have been blessed with come forward. That’s why they are who they are.

GHESQUIÈRE: But fashion, in a way, has become like pop culture today. With all of the communications and the Internet and the designers doing lines with big brands, it’s more popular than it’s ever been, but everything is all mixed together. It’s become like television or music. Do you think there’s still room for innovation in all of that?

MELLEN: Well, that is a question with many parts, and I don’t know if this will answer any of them, Nicolas, but, you know, a lot of women say to me, “Polly, why aren’t there more clothes out there that we can wear?” And I don’t agree with them! There are clothes out there that they can wear—it’s just that they don’t dare to wear them.

GHESQUIÈRE: Exactly.

MELLEN: How many times have people said to me, “I think those pants are incredible, but I could never wear them.” Well, why not? What’s so different about these pants? I wear very classic things, but maybe with a little change here or there. But I think that there are people who go to the best stores, and they have money, so money is no object, but they can’t find a pretty dress—and I think that’s their problem because the dresses are out there somewhere. So I think the answers to these questions lie somewhere in there.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you look at images or watch shows online during the fashion weeks?

MELLEN: Oh, I do. I mean, I was fascinated looking at John Galliano’s couture. My goodness! Amazing!

GHESQUIÈRE: It was really extravagant.

MELLEN: Where are you going to wear those things? They’re just extraordinary extravaganzas and I love it. I love looking at it because it’s like going to a museum.

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s very radical.

MELLEN: Radical, but couture is back there a bit.

GHESQUIÈRE: Well, couture has a lot of issues today, as you know. Here in Paris there are oddly so few houses showing. And I’m not talking about the style. I’m talking about the sense of couture and these young actresses that you were talking about—they want long dresses that are not always the most innovative or the most interesting. So it’s a bit lost.

MELLEN: I don’t know if I should say this, but it’s not modern to me. When I hear an editor say to me, “Did you really like that?” I say, “I thought it was fascinating, yes. I liked it.” And they say, “But there was nothing pretty there.” And I say, “What does that mean?” And they say, “I like pretty!” It’s like, “Oh, dear . . .”

GHESQUIÈRE: [laughs] I don’t want to play the red-carpet game, because most of the actresses today, unfortunately, are not very well-surrounded in terms of the stylists and stuff, but what do you think about the fact that, these days, actresses are on the covers of magazines more than models?

MELLEN: I think when a time comes, a change comes, and you have to recognize the change but also believe in yourself. For instance, why isn’t Tilda Swinton on the covers of tons of magazines? Well, she’s not that. It isn’t her thing. But I don’t know. I think that suddenly a time came when models, after the Linda Evangelista crowd, and Naomi [Campbell] and Christy Turlington, when the models for me became a bit bland. But I think more than that, the culture changed. The movies, television, music, and all of those things—those people were more visual and therefore more interesting. I mean, you think about Lady Gaga—for me, now, she’s starting to wear off a little, but my granddaughter, who is 11, has her picture on her headboard. I think Rihanna is very interesting. But those people, the singers especially, know how to handle themselves because they’re in the limelight. That’s why it has grown into something where the model has stepped back—and I don’t know if it’s coming forward again. I think Gisele Bündchen is amazing. I think that young Russian girl, Natalia [Vodianova], is very beautiful. But I don’t know . . . I think it’s tough on editors who are doing shoots. But it is the job of the editors to find somebody. I’m sorry, but you have to get out there and find them.

GHESQUIÈRE: What were some of the most rewarding moments for you as a fashion editor? I know that’s not an easy question to answer because there were probably many.

MELLEN: I’ve had so many. When I got my [Lifetime Achievement] award from the CFDA [in 1993], it did not just belong to me—it belonged to the many young people I worked with over the years. But I’m the kind of person who, even after a shoot that I’ve loved, is always moving on. There is no gap. I mean, with what is asked of you, Nicolas, to do one collection after another, there’s hardly any time to rest your brain. To look deeply into the lawn and see six shades of green—there is hardly that respite for you.

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s true. I can tell you that, backstage, at the end of the show, I’m already thinking of the next show.

MELLEN: And that’s our job that we’re doing. And it’s even more demanding for someone like yourself, who is so extremely creative. But you have to move forward. You cannot just wallow or sit back and take in the accolades. They’re wonderful, the accolades, and you appreciate them. But then you go on to the next moment. You have to always be going out to the end of the diving board and diving off.

GHESQUIÈRE: What do you think was the most difficult decision you had to make in your career?

MELLEN: Oh, retirement. Well, first, at a certain point, Nicolas, I wanted to have my own magazine, but I never could. Why? Because I am not commercial enough. Again, I can’t use names, but it’s pretty obvious . . . The people who would have been able to give me my own magazine, they were not insulting me, but they would simply say, “It wouldn’t work for you.” And that was a big disappointment to me. And then, I think, the most difficult thing after that was when I knew, and faced the fact, that it was time to come up here and retire with my wonderful husband, and my children and my grandchildren, and make that change. I’m not good, Nicolas, at hanging on. When I make a decision to cut it off, I have to cut it off completely. I’m not good at, “Oh, I’ll stick around and consult a little bit.” I’m not good at that and I don’t want to do that. I don’t think you get anywhere doing that. I mean, I don’t, although other people might. But that’s not my personality. It’s not my id. I have to make the break and be a good sport and adjust to it.

GHESQUIÈRE: But you’re still curious about fashion and things.

MELLEN: Absolutely. I’m always curious. Every day. As we get on in life, we must be grateful, Nicolas. You are very young and you have a wonderful, creative, and interesting life ahead of you. Why? Because of your curiosity and certain demands that you put on yourself without your even knowing it. But what we’re talking about in a way is caring. I’ve always been fascinated by people’s capacity to care. Everyone has a different capacity for it. Some people can take on more and deal with more. Today, with the economy, I have such respect for the hard work that has to be done. But we’re on this planet and we have a responsibility to ourselves to care.

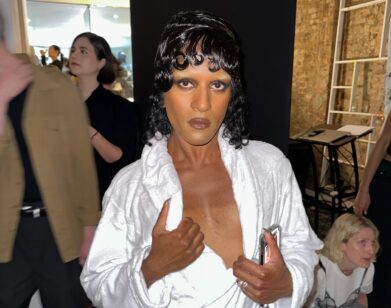

GHESQUIÈRE: Before we go, I have a little story that I wanted to tell you. You won’t remember this, but the first time we encountered each other was before I even started at Balenciaga. It was when I was an intern at Jean Paul Gaultier. I wasn’t even an assistant. I was an intern. You were walking in the show. Do you remember that?

MELLEN: Oh, the show with the wires! Yes, I do.

GHESQUIÈRE: I was there. I was in the middle of tons of people, so of course you wouldn’t remember, but I was there as an intern and I was so impressed just to see you—not even to meet you, but just to see you. So it’s a special thing for me to do this interview today.

MELLEN: I remember walking in that show! That was so much fun. I loved it. Isn’t Gaultier a wonderful man?

GHESQUIÈRE: Oh, wonderful. When I was working for him, I would watch him going everywhere and doing things, and think, Oh, my god, how is he going to mix that together and put that together? And then he was the only one to get the key to do those amazing silhouettes, so I have a lot of respect for him. He’s someone very, very special. You were great on the catwalk, Polly.

MELLEN: I was?

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes, you were. I’m really honored to have interviewed you. It’s been a real pleasure.

MELLEN: It’s been fun. Good luck with your collection. You are a genius, Nicolas.

GHESQUIÈRE: Thank you. From you, this means a lot to me. I was stressed before talking to you, like you were with Diana Vreeland.

MELLEN: [laughs] I understand that. I have a quality where I sort of scare people. But I am who I am, you know?

Nicolas Ghesquière is the creative director of Balenciaga. He was named womenswear designer of the year by the CFDA in June 2001.