Explore fashion from the 2000s as you’ve never seen it before

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

In a new exhibition titled The Overworked Body: An Anthology of 2000s Dress, Australia-born and New York-based fashion curator Matthew Linde refuses to take received wisdom for granted. He’s very clear to explain, as we step through the two mannequin-stuffed gallery spaces in Chinatown (Ludlow 38 and Mathew Gallery) that he’s using for this sprawling look at fashion from the previous decade, that the show is not meant to be “a survey or an overview.” At least, not in the rigid sense that a historian might use those terms. Rather, he points out, “It’s an anthology, meaning a selection by choice.” The show expresses Linde’s point of view about the hidden forces bubbling beneath the sartorial surface. “This approach has really been lifted from Cecil Beaton’s 1971 exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, titled Fashion: An Anthology,” he explains, adding that this was the “first instance in which fashionable modern dress received a museological moment … previously these exhibitions were done under the auspice of a dress historian, but how then can a dress historian approach the idea of fashionable modern dress?”

Linde remarks that his exhibition “hijacks this anthological approach, but to the point of ad nauseam … This exhibition presents a period of fashion that is overloaded and overworked.” His vision sweeps across a wide range of designers, from major figures like Helmut Lang and Walter Van Beirendonck, to obscurities like KEUPR/van BENTM and Hideki Seo. While a more pedantic exhibit might have skipped unknown figures in favor of designers whose clothes people actually wore, Linde uses small names to illustrate big ideas. “I’m bringing up unsung voices from the period to present that fashion history has always been slippery and complicated,” he says, with a mischievous smile. “So someone in 2050 doing an anthology of 2000s dress would do something wildly different to this. This is more of an attempt to unnerve or complicate this idea that fashion periods are cement.”

So what did the period add up to, exactly? “Prior to the 2000s you really had to be an insider to know what was going on in designer fashion,” Linde notes. “When digitization occurred, which people describe as the democratization of fashion, suddenly these wider markets were available. But at the same time you had the proliferation of fast fashion—Zara, TOPSHOP, H&M, Target. So suddenly things became a lot more ugly,” he adds, laughing. “There was so much trash in the 2000s.” Linde’s vision of the decade captures an itchy, imbalanced energy, sparked by disruptive forces like 9/11 and the rise of social media. He showcases designers who blowtorch sequins, turn prom dresses into necklaces, and fill transparent post-apocalyptic survival outfits with trash. They mock couture silhouettes and use religious garb as a punchline. Nothing was sacred. Or perhaps, everything was.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38

MATTHEW LINDE: This is KEUPR/van BENTM; there’s two of them and they met in ArtEZ, which is the fashion school in Arnhem in the Netherlands. They only operated for a few years, but for me it was incredibly important that their voice is made present within the ’00s. They only showed in couture week, as a refusal of the dominant design ethos of the late ’90s and early ’00s, which was this kind of minimalistic chic, Helmut Lang approach. They wanted to hijack the couture atelier to produce slapstick couture. So they were famously dubbed by Vogue as “Cartoon Couture,” and I think it’s evident in the flattening of the lapels up here and the carnivalesque nature.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38

LINDE: This is Hideki Seo, a 2005 graduate collection from the Antwerp Academy. So fantastic. While he didn’t go off and create his own label, it’s nice as a moment in time in fashion. Walter van Beirendonck was the fashion coordinator at the school; you see Walter’s voice being re-processed through new designers in the 2000s. Like, what would happen if Walter started designing in the 2000s?

INTERVIEW: Did Seo have a major commercial impact?

LINDE: No, I think he’s the design assistant now for Alaia. For artists, their practice often develops as their career develops and gains refinement. Fashion designers are the antithesis of this; their best work is usually their graduate work and as they become more and more accessible to the market they become more and more diffused.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38

LINDE: There’s Walter Van Beirendonck himself. Fall/Winter 2008-2009 I believe, menswear. Looking at the spectacle, carnivalesque side of fashion as it always is with Walter, it’s a kind of continual study of menswear and masculinity. He’s always trying to fuck with masculinity. Of course this is a kind of political collection, featuring burqas.

Photo by Yair Oelbaum, courtesy of MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38

MATTHEW LINDE: This is Issey Miyake from 2000. During this period, they were really looking at fabric techniques and how to produce fabrics, and this egg carton suit is a good example of that, like, “How can we continuously fuck with synthetics.” I think this is a very good example of being disrespectful somehow to the 2000s or being ahistorical, if you will. When you look at this from a kind of quick-reference hegemonic understanding, you would much easier place this in the 80s. You know what I mean? So this is actually a very good example of designers subverting the 2000s style. So a lot of people have come in here and said, “Wow this looks like the ’80s!” And it’s like, well, they were all made in the 2000s, so. [laughs]

INTERVIEW: People often say the 2000s was when so-called “retromania” blew up.

MATTHEW LINDE: Yeah a lot of subculture styles were really re-hashing each other. And if you read Wikipedia or something, they really use this idea to frame the 2000s. However, interestingly enough, [German philosopher] Walter Benjamin was talking about that same thing with regards to 1920s fashion, how it was rehashing styles. So I think this is a permanent condition of fashion, that it’s actually not linear. That one could see the present only through moments of the past returning.

Photo by Yair Oelbaum, courtesy of MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38

MATTHEW LINDE: This look is by Wendy & Jim, European designers who were working with functionality. In this piece from their 2002 collection, they made these architectural prom dresses, but they never made an opening, so it always just functioned as a necklace. So you can only wear it as a necklace, it’s one big long necklace.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

MATTHEW LINDE: This is by Kostas Murkudis, who famously worked for Helmut Lang throughout the ’90s and started his own label in late ’98. This vest is like a link to the Lang-ian past that he had. Both in terms of the very minimalist approach, but also playing this line between sexy d’amour and like, horny. [laughs] And obviously using a transparent fabric as well.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

MATTHEW LINDE: This is a look by Shelley Fox, who is a British designer. This is from her signature 2000 collection in which she blowtorched sequins as a material motif. She was poached by Parsons, here in New York, in 2011 to start the MA fashion program, which she is still the director of. So she is part of the few scholarly designers in this exhibit, that mostly operate in the academy context.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

LINDE: This is by Ben Cho, who died earlier this year. He was part of an early New York downtown group with designers like As Four and Imitation of Christ that were very mediated by sociability. So they’d go out, they would party together. Cho also DJed, and was good friends with Chloë Sevigny. His collections almost never had a continual binding theme, as they were more like material exhibitions. He was very famous for making this kind of D-link bondage system as a bodice, which famously Versace apparently stole. [laughs]

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

MATTHEW LINDE: This outfit is by Narciso Rodriguez, which was from his 2001 collection that was set to debut on the afternoon of 9/11, so of course it never went to show. So this is fantastic that we have it here because it’s kind of a lost collection.

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

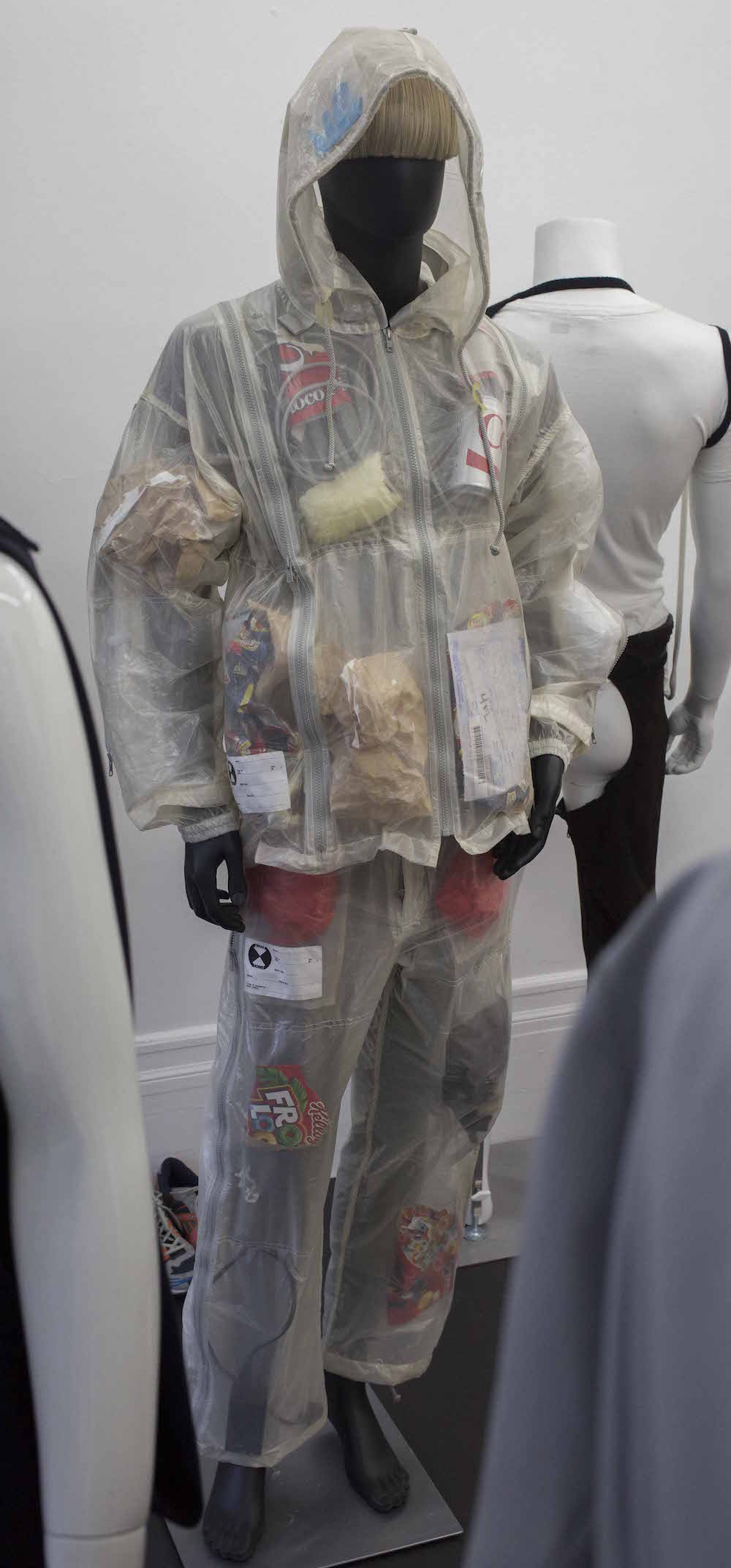

MATTHEW LINDE: This is by Japanese design house called FINAL HOME, who make this kind of post-apocalyptic wear, where you just stuff things in, in all these compartments.

INTERVIEW: Did it come with these things inside?

LINDE: No, he was like, “Just stuff your own stuff!” We were literally stuffing this as the exhibition was opening so we had no time, we were like, “Whatever’s here, just put it in!” [laughs]

Photo by Dillon Sachs, courtesy of Mathew Gallery

MATTHEW LINDE: These are all by Ann-Sofie Back, these sunglasses and this corporate blouse with this disgusting disco material. You can wear it different ways; look at this deflated boob action. The most disgusting place you could put a box pleat, that’s where she placed it. Likewise, a little mountaineering belt on these corporate slacks where the side seams are rotating 360 degrees. Here, note the biennial corporate jacket but with two extra sets of sleeves.

THE OVERWORKED BODY CONCLUDES TONIGHT WITH A RUNWAY PERFORMANCE OF PIECES FROM THE EXHIBITION; FIND OUT MORE HERE.