Meet the photographer behind Yohji Yamamoto’s stunning campaigns

Photographer Max Vadukul knows how to take a good picture. Born in Kenya, Vadukul, who is Indian, was transplanted with his family to England, where he spent his adolescence in a working-class town outside London. Refusing to accept the life that was seemingly destined for him, Vadukul climbed the fashion world’s hierarchies as he became known for his iconic black and white imagery.

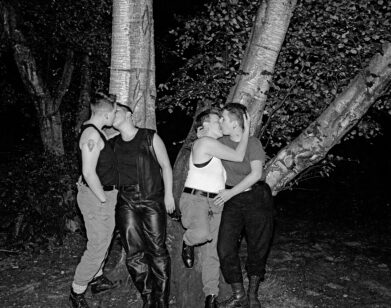

A self-described artistic autocrat, Vadukul has mastered the art of what it takes to create a lasting image—you know a Vadukul photo when you see one. In the 90s, many of his photos shook the fashion world with a style that rejected advertiser-driven narratives. Instead, Vadukul developed his signature guerrilla style of shooting in black and white, capturing the grit and emotion of New York City.

Throughout his 27-year relationship as a collaborator with Japanese designer Yohji Yamamoto, Vadukul traveled the world shooting Yamamoto’s timeless campaigns. From there, a linear trajectory can be drawn through his development as an auteur: he’s shot for Vogue Paris, served a five-year run as a staff photographer at the New Yorker, as well as contributing to Interview, W, and Rolling Stone.

Vadukul’s images are full of secrets that only the photographer and his subjects share—and the devil really is in the details, if only you pay close enough attention. “I belong to a generation that is brought up to think for themselves and the mentality that there is a recognizable signature,” he says. “We used to all look at each other’s [work] to make sure we didn’t look like anyone else’s. Today, it’s really difficult to tell who shot what. The work I’m really known for is Yohji [Yamamoto], French Vogue in the ’90s and the New Yorker with Tina Brown.”

The present generation’s fascination with the ’90s and a nostalgia for analog may have reframed Vadukul’s photography in a new light, but his pre-millennial training was that of ultimate dedication to the work. “For me, it was always about strength, character and the possibility to create a lasting picture,” Vadukul says. Speaking further to the generational differences, he says, “Did I ever complain about being marginalized? No, I never complained. Why? Because I’m good. I don’t care about anything or anyone, I simply care that my work is good.”

Here, Vadukul selects some of his greatest pictures, and walks us through how they happened.

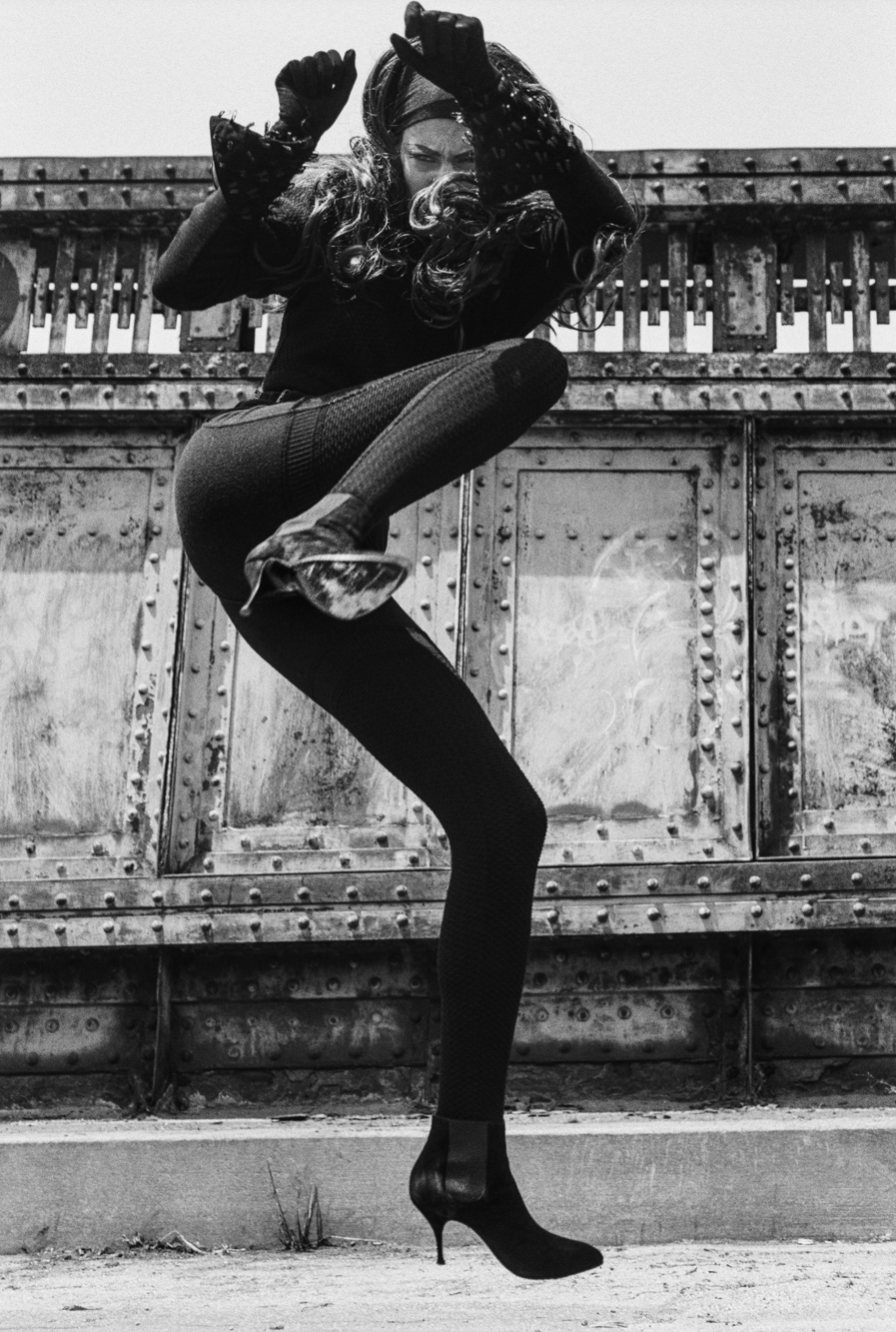

MAX VADUKUL: Today, you do shoots with a moodboard. The spontaneity isn’t there. Remove anything risky so we don’t get slammed by social media. Freedom of thought, freedom of speech, freedom of thinking is removed. What you’re looking at—the model on the horse and the girl floating behind the zombie man with the briefcase (above), that is the work of an auteur, that is a dictatorship. A certain kind of photographer is not democratic, it’s a dictatorial process.

Permission was given by Yohji to shoot this project the way I wanted to do it. I was given total carte blanche. Luckily for everybody, I don’t know how to do vulgar photography. For the life of me, I tried to do nudes, it’s near impossible—the “hot” picture.

The girl on the horse is shot in Luna Park in Rome, and the one with the man is shot in New York City. I love cities with a muscular personality. I’ve done pretty much every line of [Yohji’s] brand for 27 years. There isn’t one other photographer who’s done that. It’s a remarkable relationship with the brand in my own medium, black and white. They never asked me to do anything I don’t want to do.

We have to keep in mind that designers like Rei Kawakubo and Yohji are very unusual for the Western mind. They are deeply respectful of who they ask—you have to take a Samurai principle of nobility. They’re never going to ask you to do anything that would upset you. Once they commission you, it really is an honor and you do what you like.

These pictures were a shock to the fashion world. They have an elegant violence to them. They sent tremors down the industry. Back then, the photographer had the power. That’s the extraordinary thing about these pictures: They’re born out of chaos. I like to get order out of chaos. The shot in New York with the girl is not the result of being agreeable and definitely not the result of somebody who is into going with trends.

VADUKUL: I would dub the cat on the roof the most underestimated fashion photograph of all time. This should go alongside Avedon’s photo of Dovima and the elephants. It’s a phenomenal photo in my opinion. Firstly, it’s Versace’s first haute couture collection. Secondly, it’s shot on the rooftop of the old French Vogue on Palais Bourbon. The model is Leslie Navajo. The cat happened to be there—we cast a professional cat that came with a trainer. I was fascinated by roofs and I loved the idea of having cats in pictures. The cat and the girl are mirroring each other in their movements. It was an incredible partnership with my wife, Nicoletta Santoro. I like to put little secrets in pictures. There is a darkness, that’s why I call it an elegant violence, but it’s not dangerous. I feel a sense of strength in the pictures.

VADUKUL: That picture was featured on the front page of the New York Times Style section. The journalist had written that this photograph was taking fashion photography to fine art. It was part of a pret-a-porter story for French Vogue. The Indian photographer wanted to work with Linda … We never used to think in those terms before. It was my first 16-page story for French Vogue. It started to rain non-stop and I shot those 16 pages in one day. This was shot on the High Line. None of these pictures are retouched. When you see the girls in my pictures, they’ve never had an airbrush to them. I think today, if you started out, you’d have to be a playboy with a trust fund. I have the power to straddle two worlds—the past and the future. The picture I showed you is impossible to do now for a major mainstream magazine.

VADUKUL: The New Yorker is a very important part of my life because it was a five-year contract. It was at a time when Richard Avedon was the chief photographer, I was the staff photographer and Helmut Newton was working there too. I had to shoot 54 assignments a year. During that period, commercial work had to be sidelined. Tina Brown [the editor] wanted an intelligent photographer to work with—I was the happiest man there. I got to photograph 40 Nobel laureates in one picture in San Francisco, I got to photograph Mother Teresa in New Delhi, I’ve done all the writers of Modern India English for the India issue, I got to photograph the Indian Freedom Fighters from the British Independence Movement and they all came dressed in their uniforms from the ’40s. The leader was a lady [named Lakshmi], she’s amazing. The New Yorker was a fascinating departure from the glossy world of fashion.

VADUKUL: When I went to photograph [Mother Teresa], it was drummed into my mind that she was kind of a crook. I get there and it really wasn’t like that. She’s working to make other people’s lives better. She would do things that most people would be ashamed of doing. I’m sure in the past, she has scrubbed the floor.

VADUKUL: [Tom Hanks] was driving [on the Pacific Coast Highway]. I just needed to be alone with him and remove him from the publicist. I took him for a ride around Malibu and he was driving in this convertible and I think there’s a traffic jam and it was Halloween day. This car rolled up with a mask, but they didn’t know it was Tom Hanks. When I saw [the mask], I said, “Do Home Alone, Tom, quickly!” And that’s what happened. It was really fast. It’s funny, because I couldn’t have planned this.

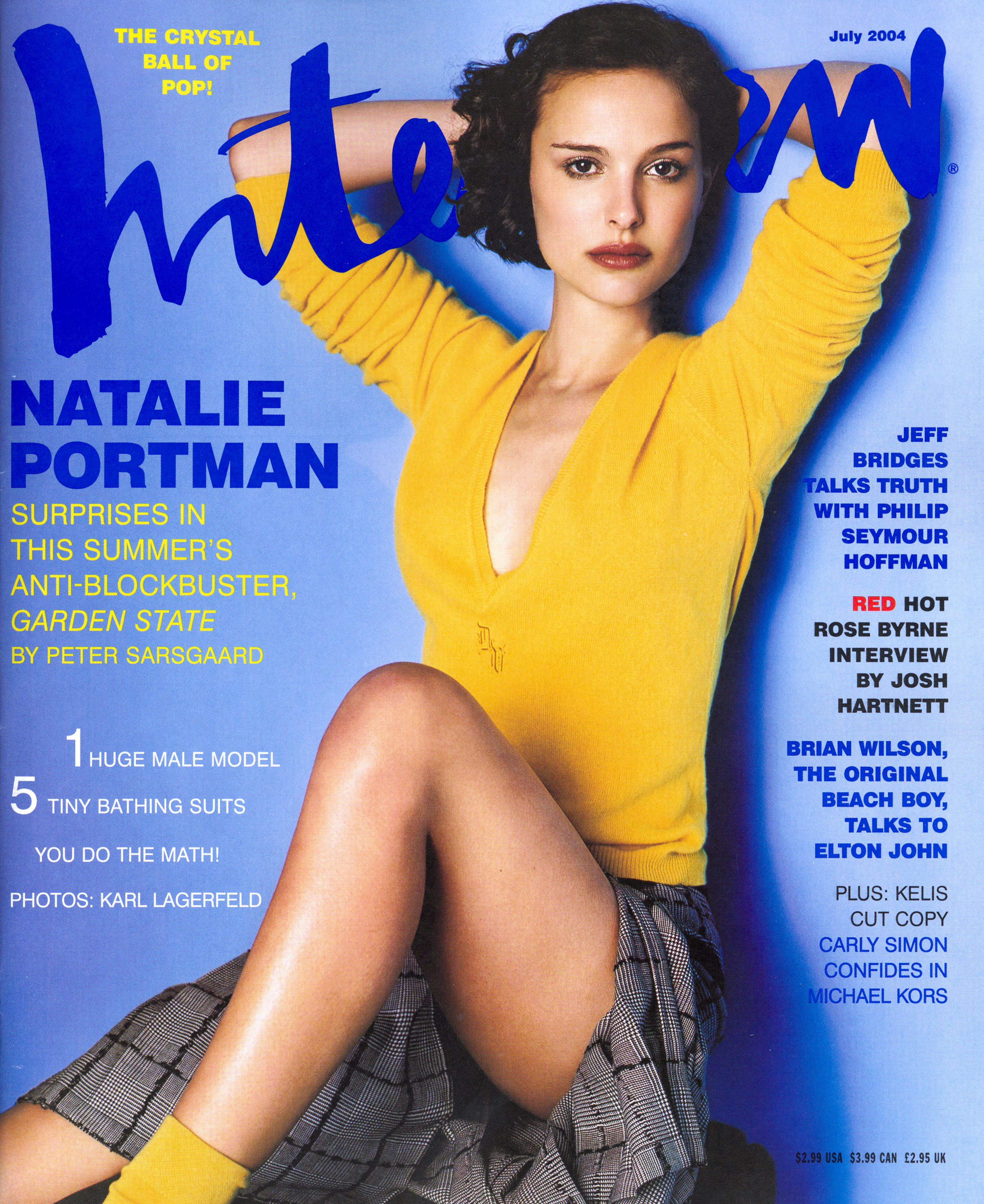

VADUKUL: Ingrid [Sischy] was possibly one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met. We used to talk about [photographer] Sebastião Salgado. She would say, what would you think about him? I said he was like the photographer of economics, because he was always shooting a lot of workers in Brazil. I always saw Interview as very celebrity-driven, but Ingrid was something else. Behind the façade of the celebrity world, she was really into serious photography. Doing the covers for her was fun because we would get on the phone. She was very good at giving me directions. Ingrid was great because I would go in to choose the pictures with her.

You’ve just done a picture of Natalie Portman, and it’s a little bit Balthus-inspired, but it’s Interview so it’s got a little bit of pop to it. The actresses were captured with intimacy.

VADUKUL: I think [Hilary Swank] just won the Oscar for Million Dollar Baby. I got really tired of the studio and I said, this is boring, can we just go out? And that’s what happened. We just went around the corner and found a bodega. She got on top of this ladder and there it is. It all happened very quickly.

VADUKUL: This shot with Clint Eastwood was done in 60 seconds, flat. Because I only had 60 seconds. I was sent up there to photograph him and was told I had 20 minutes. His manager looked at me and said I’ve got 60 seconds. I loaded the camera and started to work with him. When I finished the roll of film, he looked at me and said, “Kid, did you get it?” I said, I have no idea.

VADUKUL: The Amy Winehouse picture is a great example of the approach to complicated artists who have left their home, their world, their comfort, and are no long private … They are public property. The public owns them. This particular situation was on the day of her wedding. I shot her wedding for her. That picture is in the hotel in Miami. Before we did this, she said, “You have to photograph my wedding, Max.” I said, “When is it?” She goes, “Now!” I said, “No we have to work first.” She said, “Come on, just 15 minutes. Do pictures of me and my husband together, we don’t want anyone to know.” The day just unraveled into a bit of a nightmare. The picture you’re looking at is directed and then she was caught off-moment here. Straight after that, we did the cover and then I really lost her, because after 15 frames of shooting the cover, she just got up and wanted to leave. And then I didn’t see her again. Her life became very difficult.