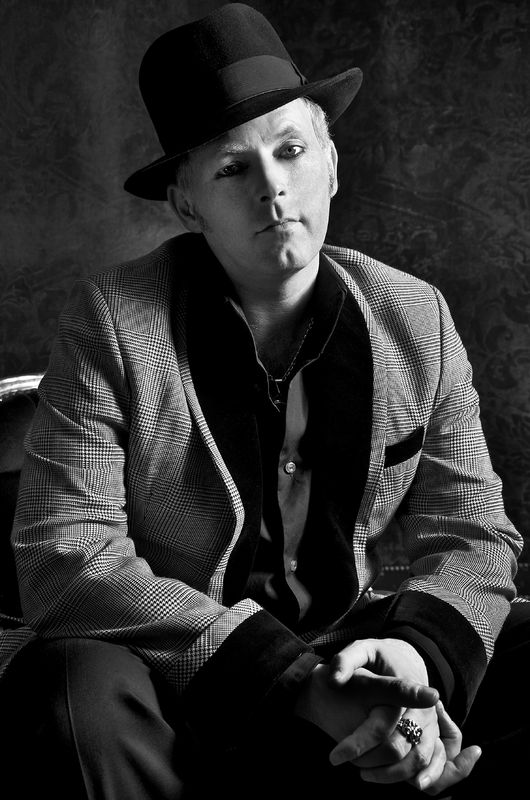

Joe Corré, 21st Century Teddy Boy

“I find fashion boring,” says Joe Corré, a statement you wouldn’t expect to hear from the founder of Agent Provocateur and progeny of the King and Queen of Punk, Dame Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. “I like dressing up and wearing good quality clothing. I like looking different, but fashion is about following trends and buying homogenous clothes,” he proffers.

Since 2008, designer and social activist Corré has been working on his London-based brand, A Child of the Jago, as an antidote to mass-produced, eco-unconscious fashion. His eclectic and anarchist vision translates a melting pot of designs celebrating individualism—reconstructing and reinterpreting antique cloths with a nod to the past but a contemporary punch of personality.

KATE LAWSON: So the name of your brand comes from the book by Arthur Morrison, which in part revealed how criminals would use fashion to replicate the pomp of Victorian London in order to escape the depravity and poverty of the slums. Why was that book a starting point for you?

JOE CORRÉ: When I read the book, it really depicted what life was like around the area of Shoreditch where our Jago store is now situated. Throughout my formative years in London growing up, the things my Mum and Dad were interested in were Dickensian stories such as Oliver Twist and King Mob, which was a reference to the Gordon Riots in London. It was a time when people really understood the quality of clothing, and at that time it was made on a smaller scale, not mass production—clothes were made by a tailor and shoes by a cobbler. Criminals at that time liked to put on a show, which is what differentiated them from other people and gave them their character. The cockney language and characters such as the Artful Dodger, Oliver Twist, and Jack Sheppard were all showmen, and I guess it is the theatrical elements and the theatre of the street that fascinates me.

LAWSON: The influence of your iconic punk-heritage is also obvious in your designs—how did the idea of fusing that with the gritty past of the East End’s characters come about?

CORRÉ: When you look at an image of the Artful Dodger as a kid wearing old man’s clothing—his coat tails are too long and drag on the floor, his sleeves are too long and covering his hand, his hat’s too big and it’s all bashed in—he has taken something that is good quality but is far too big for him and he’s dressed up in an adult world. There is a comedy in it, a sort of feeling of self-importance that goes with it. That’s where punk meets not just the East End, but that kind of Dickensian character. There are a lot of influences like that in punk.

LAWSON: So how did you source the characters you chose as inspiration for your designs? Where else did you reference from?

CORRÉ: It comes naturally really, but one of our most popular suits is the “threepenny jacket,” which is influenced by the movie, The Threepenny Opera (1931) about the life of Jack Sheppard (the historical thief in John Gay’s 18th-century production The Beggar’s Opera). In the movie, Mackie Messer, aka Mack the Knife, wore the suit and I copied it as it was very dandy and spiky with sharp lapels. In our women’s collection, the “Bessie” dress comes from the girlfriend of Jack Sheppard, who was a prostitute, and our “Nancy” dress is taken from Oliver Twist. I thought these names best represented the characters of where the clothes have come from and the way they all relate to each other.

LAWSON: It must have been quite a strange transition moving into dandy tailoring and cheeky East End rogues, from cheeky knickers and bras at Agent P?

CORRÉ: After knickers and underwear I wanted to do something that was refreshing to me. I wanted clothes that I could wear and I didn’t really want to buy existing menswear as nothing really interested me. I wore my mother’s designs for most of my life and got to a point that I found I had everything, really. Even when I went to a fashion show, I would always want the more dandy pieces and they are the ones that wouldn’t actually get produced. I felt like I wanted to do what I had been doing all of my life, but in a different way, this time keeping it smaller and making it an anti-brand so it couldn’t expand as much.

LAWSON: From the past to the present, then—are there any key influencers who define the culture of the East End now for you in terms of attitude and style?

CORRÉ: I can only really talk about the past when we talk about the culture of the East End, and what I really liked was the music hall period and the showman side of things. When I was a little kid I went to Brick Lane with my dad and mum on a Sunday, it was predominantly a Jewish market and my dad had a Teddy Boy shop on the Kings Road in 1973. I must have been about six years old, and they used to deal secondhand clothes in bales. Each one-ton bale was all strapped up and bought by weight, then the Jewish dealers would cut it open on the street so people could rummage through and buy what they wanted. My father used to take us early in the morning to look for old Edwardian waistcoats and top coats—Teddy Boys would dress in Edwardian style, long coats with long lapels and low breaks where the button was. In the East End there were the popular songs such as “Any Old Iron” and Lily Morris’ “My Old Man Said Follow the Van.” That whole music hall era bred huge heroes in entertainment, and those characters later featured in West End theater shows.

LAWSON: Do you think London is still the beating subcultural heart of it all, in terms of British designers competing on a global and commercial stage?

CORRÉ: I don’t think people should perform on a global stage, they should perform on a local stage to a local audience. The Stone Roses wanted to be the biggest band on their street, not the biggest band in the world. Trying to be commercial is a waste of time. It’s not about being commercial but being intelligent. London is not the subcultural center of it anymore—it’s a great city with a lot of opportunity, but so ridiculously expensive and it has been taken over by brands and is now losing subcultural influence on anything. To get that back we have to perform locally, not globally.

LAWSON: You’re very socially conscious and politically active when it comes to fashion and the environment—do you think the industry should be doing more to promote sustainability, and as consumers we should be more aware of anti-disposable labels?

CORRÉ: Yes. We all live in such a disposable world with full wardrobes that we keep adding to, so yes I think people should buy less and buy better. My brother is a perfect example. He takes it too far, wearing things that are literally falling off him, but he still looks more interesting for it. The other thing is that people have become used to the idea of how clothing now splits in the market; supermarket level and high-street at one end where there is always something new that always falls apart, and then the higher-end pieces that cost a lot of money. I don’t understand why it has to be like that, I don’t agree that high quality clothing has to be that expensive. The way our label produces things is different, we buy fabrics cheap as end of lines and pass that cost benefit onto our customers. We are not wholesaling products, which means we don’t have to increase our prices in order to keep them in line with anyone—we don’t really fit into the fashion market.

LAWSON: Talking of the market, men’s fashion is booming again with more and more labels choosing to show at London Collections Men. What’s your take on it all and how it will evolve?

CORRÉ: We did a few shows at LC:M but it just didn’t sit well with us as a brand and wasn’t right for us. Also the majority of people showing don’t make anything in the UK so I don’t know how British that really is. I don’t know that men’s fashion is on the rise; maybe there are more designers, which is great, but make it here and make it in a sustainable way. In terms of it evolving, I am not so interested in fashion or LC:M or the men’s fashion market; I am more into men getting a local tailor and getting them to fit their clothes perfectly so they look more interesting.

LAWSON: You’ve now introduced women’s pieces into the fold. Was it difficult to move into dressing the female form?

CORRÉ: It was difficult, but I have had a go and made quite a good start. My mum came in to give me pointers and advice and she really likes what we are doing and her pointers were good. I would like to work with an in-house womenswear designer moving forward. I made a decision to make clothes that last for a long time and that won’t go out of fashion and I think it is easier for women to dress up than men.

LAWSON: On the art of dressing up, your brand philosophy cites the expression “the street is your stage,” what is your personal opinion on the rise of street style photography and the notion of “peacocking” for the camera?

CORRÉ: This has been going on ever since I can remember, since the birth of i-D magazine and even before that. I do like it, there is a huge set of people who like dressing up and showing off. I think it’s great!

LAWSON: A bit like Pharrell wearing your Mum’s “Buffalo” hat design, which was one of this year’s most-talked-about fashion statements, if you could dress one particular loaf of bread with one of your own unique hat styles, who would it be?

CORRÉ: Edward Snowden. He would need a good hat and I feel our clothes are quite heroic and I have a lot of heroes that are quite unconventional. Edward Snowden is very prolific and he would look great in one of our hats, it would be a pleasure to dress him.

LAWSON: Yes, he would make an interesting muse! And what about your own personal style, how has it evolved over the years?

CORRÉ: In so many different ways. I like changing my look and I like dressing up. I also like taking the same clothes and wearing them in different ways. If anything I’m a bit freer now. It’s good to have childish elements too. I like clothes and I like details and it’s still evolving.

LAWSON: What about the future, what’s in store for A Child of the Jago?

CORRÉ: It’s important to have independent stores that do special things. I don’t see A Child of the Jago being a massive brand, I don’t want it to be that. I don’t want to fit in with any kind of fashion business formula as I’m just not interested in it. I just want to dress people with an intelligent brain, people who don’t want to fit in with the fashion or political system.

FOR MORE ON A CHILD OF THE JAGO, VISIT THE LABEL’S WEBSITE.