in conversation

Will Sharpe and Olivia Colman on the Art of Winging It

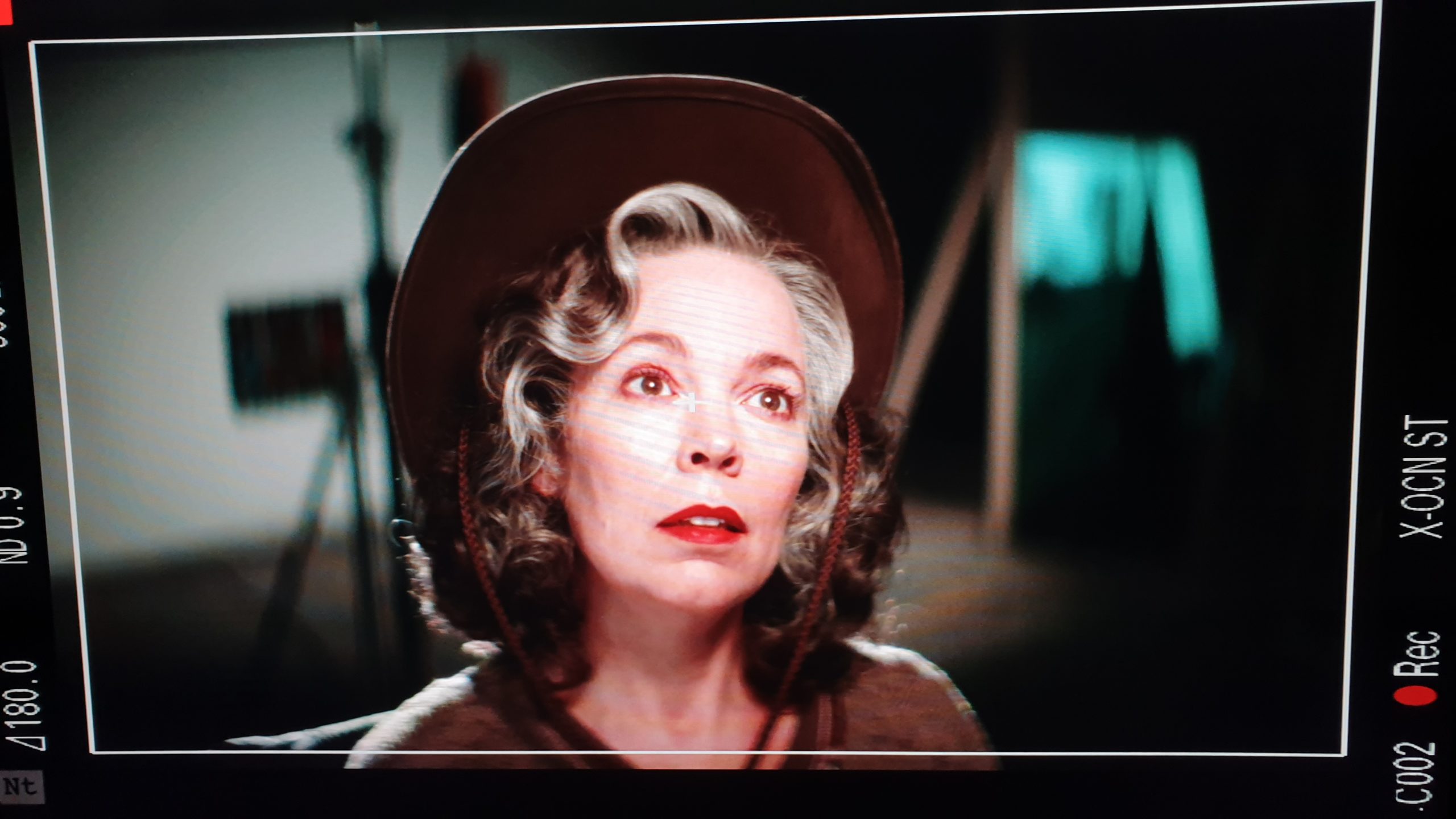

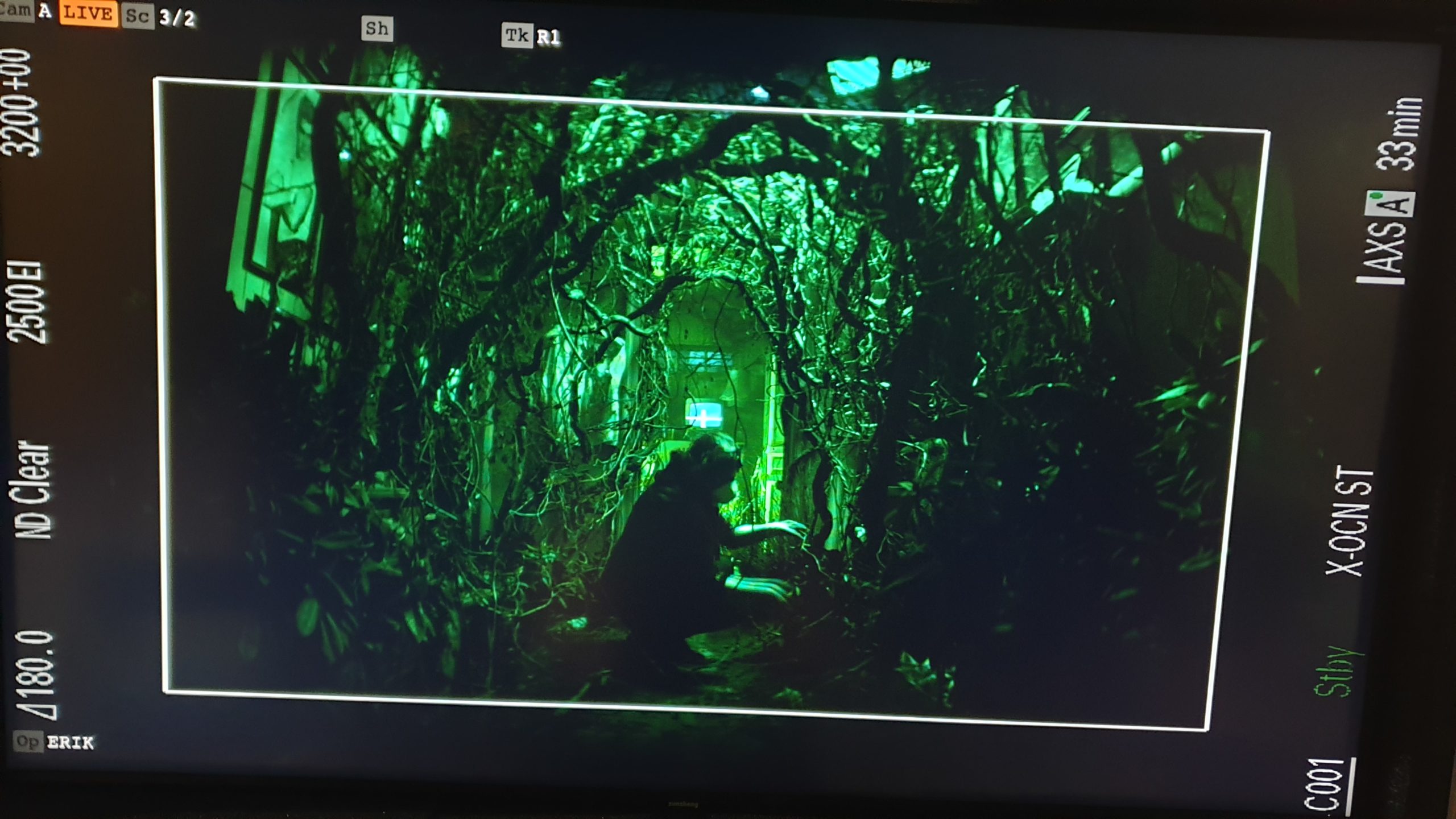

You may know the writer, director, and actor Will Sharpe from shows like FLOWERS and the BBC drama Giri/Haji—which earned him a BAFTA for best supporting actor in 2020—but it’s only recently that the 35-year-old English-Japanese multihyphenate is receiving acclaim for his off-camera skills. This fall, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain—a comedic drama directed by Sharpe and starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Claire Foy—was nominated for several British Independent Film awards. This month’s Landscapers, an HBO Max miniseries co-written and directed by Sharpe, is raking in the accolades for its inventive approach to dark comedy. Based on a true story, the series stars David Thewlis and Olivia Colman, a quirky but seemingly ordinary British couple who are caught with two dead bodies buried in their back garden. On the occasion of the show’s December premiere, Colman caught up with Sharpe to discuss childhood dreams, method acting, and future dinner-dates.

———

WILL SHARPE: Hi, Olivia!

OLIVIA COLMAN: Hello! How are you doing?

SHARPE: I’m good. I’m excited to talk with you about Landscapers. You know, I’m a big comedy fan. I loved Peep Show and Green Wing. But it wasn’t until I saw [the 2011 drama] Tyrannosaur that I really felt like I got a sense of the full range of what you’re capable of. I saw that you could probably do anything. But did you have a sense, as you headed into production on that film, that you were doing something entirely different or new? And has it felt like that job changed anything for you?

COLMAN: I think it probably did. I do thank Paddy [Considine] a lot when I get the opportunity to, because there was no reason for him to give me that part based on the work of mine that he’d seen. It only takes one person to take a leap of faith, or to see something in you, I suppose. But I was absolutely terrified. Representing someone like that on-screen, it’s a responsibility. You don’t want anyone who’s watching the film, or who’s experienced anything like it, to feel misrepresented. You don’t want to let them down.

SHARPE: Absolutely. Does your approach change when the subject matter gets heavier or more sensitive?

COLMAN: Wooh! I don’t know. You’ve had that experience yourself. I don’t know that it does. In really simplistic terms, you just have to do the learning of the lines. [Laughs]

SHARPE: Yeah, yeah.

COLMAN: I suppose the approach should be different, but I’ve never thought about that, which probably means it isn’t. In reality, maybe it takes an hour longer to get you in the right headspace right before you shoot. Well, is it different for you?

SHARPE: I don’t think it would be. I haven’t played that many parts. The heaviest part I played was someone struggling with addiction and a self-destructive streak. But I suppose I know what you mean. There is a feeling of wanting to do right by the story. It’s like a Venn diagram, and your character’s trying to find that middle bit. From a writing or directing point of view, you want to make sure that you’re—how do I put this? That you’re handling the subject matter sensitively, fairly, and in a nuanced way. One of the first things that I really loved about the project [Landscapers] was that it was a very empathetic project. I definitely felt that I understood the story in a first-hand way, but equally sensed how one could send the wrong message or say the wrong thing in representing it. That was quite a big consideration, in the making of the show. But I don’t know about the performing side.

COLMAN: Well I think that the responsibility lies in the script. I know, I’m so boring, but when the script is good enough, it’s all there. That’s a huge responsibility for the writer, because they’ll have had to do so much research if they’re going to do it well. It’s the same with that Flowers script. By the time I got there, you’d done all that stuffy research. It’s easier when the script is good, I can trust it. Does that make sense?

SHARPE: It does, yeah. You said at a Q&A the other night that you’re not a method actor. I feel that after having spent some time with you on set, I do get that sense that you’re able to get in and out of it. It almost feels like you’ve got ready access to—

COLMAN: I find it hard to hold things in. I think method actors don’t understand how you can let go of the method. When you’re in it that deep, I don’t know how you come out of it again. I’m not really up for that. I like to be able to have a good cry, a good shout, and then leave set and have a good laugh. I think it’s sort of quite necessary. But people do work in different ways to get themselves to the place they’re expected to be. It’s just business for me. [Laughs]

SHARPE: That sounds like the healthiest way of going at it. I’m always really impressed by that, with you. Some people take six months to get to a place. You seem to get there in about four minutes.

[Both laugh]

COLMAN: Thanks, Will.

SHARPE: Maybe this is a strange question to ask, but did Landscapers feel different because the dialogue was written by Ed [Sinclair]? You know, performing your husband’s work.

COLMAN: No, that never crossed my mind. It didn’t feel different with Ed. Although he’s had so many people in his work, he has been writing for years and I knew he was brilliant at it. It’s really good dialogue, and I knew he was emotionally intelligent. The dialogue is good that it’s easier to learn. He tapped into the character’s emotions very quickly, and sort of made my job easy. Both of you did. You both write beautifully. The collaboration between the two of you was a proper treat. The only thing was, when I first read the script, I went to Ed and asked, “Can I check something with you? Is this something that’s appealing, or not?” It was the interview scene, where my character dips into the emotion, and comes out and has to repeat again. I don’t know if I’d have preferred to do the scenes separately. We all knew, coming in, that I never get to do that, so I loves trying that.

SHARPE: That was definitely, you know, one of the most fun days on set.

COLMAN: Did that appeal to you when you saw those scenes? Do you look at it as a director, or do you look at it as a performer? You’ve got all of those things in your pocket.

SHARPE: I guess with directing Landscapers, I wasn’t really thinking about it from an actor’s point of view. But I guess that you are trying to imagine how the actor might do it, or how the actor might handle it. So maybe some of it was about, you know, how long can we sustain a scene like this? I feel like the fact that there were these kinds of formal ideas, you know, about different ways to tell the story, that helped.

COLMAN: Did that appeal to your visual genius, rather than your writing genius?

SHARPE: I think the short answer is that it felt ambitious in an exciting way. It didn’t feel like a challenge. It didn’t feel like we couldn’t immediately picture the result. You know, around the time when we first started talking about Landscapers, and we were out in Atlanta, and I did find myself getting nervous, thinking about it all the time. I would wake up in the middle of the night thinking, “I don’t know how to direct a scene.” It got under my skin.

COLMAN: That’s interesting. Well, one of the many reasons why I would never want to be a director is the responsibility—and the fact that you spend weeks, months preparing, only to have us shoot that in a matter of days. And what sort of light? What lens? I’d hate that. I didn’t experience that same feeling of losing sleep, because I knew that my role was in someone else’s hands. I could learn my lines and stand up on the day. And you don’t get any breaks during filming, either. I get to have a cup of tea every now and then, and you don’t.

SHARPE: It goes the other way though. I sometimes use the analogy that it’s like getting everywhere on a bicycle, and then you upgrade to a car. You kind of remember how traveling used to feel on that bicycle, and maybe it makes you a bit more mindful. Like, if something’s gone wrong, or if the actors have been waiting around for three hours, I feel like I have a slightly more profound awareness of that, and how they might be feeling about it. But I’ve definitely felt, when I’m on a project as an actor and it’s 4 p.m., then it’s 5 p.m., and we’re still sitting around, that the plan needs to be adapted. With all that pressure and adrenaline, I’ve definitely felt that wave of relief of not having to worry about it. I can walk away and allow some space for it to be worked out.

COLMAN: I love that panicky last hour on a Friday.

SHARPE: [Laughs]

COLMAN: It’s that sort of, “Come on!” It’s that sort of, “We can do this. We can get through this.” Everybody wants to go home.

SHARPE: Sometimes, really good stuff comes out of that. If you’ve got a cast and crew that’s working together nicely, then those sort of challenges become exciting. And it’s really rewarding when you pull them off. I can imagine that when it’s not working out, it might be really stressful. I have been lucky so far, working with really nice people.

COLMAN: Well the thing about Landscapers is that we’re all so lucky that everyone on the project is so amazing. Upright and totally committed. Have you always wanted to direct? Or, did you have a first love? Have performing and directing and writing always gone hand in hand? You do everything, it’s annoying. You’ve got a BAFTA for acting, and a BAFTA for writing.

SHARPE: I don’t think I’ve got BAFTA for writing.

COLMAN: Oh I thought you got a BAFTA for Flowers, for writing.

SHARPE: I don’t—someone asked me if I had one! But I always liked writing stories and poems.

COLMAN: I didn’t know that.

SHARPE: When I was like six, I kind of wanted to be a footballer. Like, I remember going to watch a football match with my dad and my brother, and thinking it was the most exciting thing ever. As you become a young teenager, you sort of start to realize, “Okay, you’re never ever going to be a footballer.”

[Both laugh]

COLMAN: You have to have that realization.

SHARPE: There was never any shadow of a doubt that that was never going to happen. But tittle by little I started to feel—I don’t know if confident is the right word—but like I loved writing and entertaining, I suppose. I found myself compelled to do it. I didn’t mind that it took ages and that it was quite painful, often. Trying to get a script out. When I first moved to London, I fell in love with the thrill of kind of getting on the tube and scrambling around to find whatever open mic night was available. Even if it was just seven people in the corner of the pub, it still helped. I don’t know.

COLMAN: You did open mic nights?

SHARPE: Well, I tried when I moved to London.

COLMAN: Look at you! Bravery.

SHARPE: And they often went quite badly.

COLMAN: [Laughs]

SHARPE: Did you always know? Or did you have a moment? Wow, maybe I should try and think of my own answer for questions like this.

COLMAN: Well, I was really not very good at school. I didn’t excel, really. I found it hard to concentrate, and then I did my first play when I was sixteen. Actually, I think that was the first time where I thought, “Oh, I think I’m quite good at this. I wonder, Can one do this for a living?” I didn’t know anyone who worked in that world, so I didn’t know that you actually could. You have to come from it. You know? I think that play, standing on stage, seeing people applauding, it felt like a job. That was a memorable moment. I think from that moment, I never really let go. Even when I tried to pretend to be other things, I really wanted to do that.

SHARPE: I can imagine that. It’s so hard—I didn’t really know anyone from the industry either. I guess it’s hard to imagine how you would ever start. I remember hearing a talk or something, and the speaker was saying that everybody in this line of work is just winging it. Nobody really knows what they’re doing. Everyone is just trying not to get found out, day by day, scene by scene. I remember finding that really inspiring, and kind of reassuring. Because it definitely feels like you’re not supposed to consider this a job. [Laughs]

COLMAN: Yeah, it’s just too much fun. You can’t enjoy your job this much. Or, in the early days when you’re not getting the work, you’re like, “Why do I still want to do this even though no one will look twice at me?” There must be something in it that makes me keep wanting to do it. I was going to ask you, looking forward, do you see yourself leaning into one strength more than another? Or will you always want to be a writer, director, and actor? Is there one thing that your heart is really happiest with?

SHARPE: I don’t know, it’s a good question. In some ways, I sort of feel like they’re all related. They all feel like storytelling, in a way. I’ve never had a plan, and I don’t have a plan now either. I haven’t acted for quite a while now. I definitely really miss it.

COLMAN: Do you really miss it?

SHARPE: I do. I’ve always been motivated when I find scripts that leave me thinking about them. Those ones that stick with you, you find yourself auditioning for it, or wanting to meet about it. I feel like that’s been my first step. But then—I’ve always wanted to generate my own stuff, I think.

COLMAN: I totally agree about having absolutely no plan. And you know, people say, “How did you get into acting?” I don’t know! Or, “What would be your advice?” I really don’t know, because every person I know in this industry has got a different story. There’s no way of doing it. And having a plan is, I don’t think, possible. Or certainly, that’s a surefire way to be disappointed. Hoping the next thing comes along. In a sliding doors life, what do you wish you were better at?

SHARPE: In a sliding doors life, what do I wish I could be better at? You know, watching cookery shows. Sometimes, when you’re working in drama, you get home and the thought of watching an intense film like the ones you work on does not appeal. Sometimes I’m like, “I’d rather watch Great British Baking Show and just relax.” I really love cookery shows. I can cook a meal, but I’m not a great cook. I think I enjoy it because there’s a creative aspect. And also I just love eating food.

COLMAN: I wish I could, but it’s like alchemy to me. Some people can look in a fridge and see a whole creation, but all I see is one onion and a rubber band.

SHARPE: [Laughs]

COLMAN: You know, food is love. I wish I was gifted with a sort of physical skill. I find it really humbling when you watch somebody who’s really physically brilliant at something, like a dancer or an athlete. That seems so far beyond me.

SHARPE: A gymnast.

COLMAN: Oh, imagine being a gymnast. Or, oh, someone who can play the cello, who can make incredible music. But sadly, it was never meant to be.

SHARPE: Maybe a role will come up where you can train to do a backflip.

COLMAN: That’s really unlikely. That would be tough. I’m now scrambling on what to ask you now. Okay Will, you ask one. [Laughs]

SHARPE: What’s your favorite pasta shape?

COLMAN: Oh, nice! That’s tricky, Will. Because the beauty of it is that they’re so different and work best with different sauces. I do love spaghetti. I love spooling it onto your fork and just shoving it in. I do love a really thin ravioli. They’re like little presents. You?

SHARPE: I like tagliatelle, it’s like a big ribbon and it’s really satisfying. You can still twirl it like spaghetti, but it’s sort of chunky.

COLMA: Right. Next time you come to our house, we’re having pasta.