Lynne Tillman is Risen

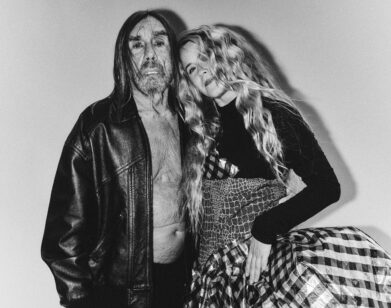

ABOVE: LYNNE TILLMAN. PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO

There is a bronze statue of writer Hans Christian Anderson reading a book and conferring with a duck in Central Park. I would hereby like to propose a bronze statue of writer Lynne Tillman hurrying down East 10th Street with a pen in her hand on the way to an event or opening or talk or a dinner. Tillman is a New York gift, a literary thinker who, in her non-fiction, tackles a topic not with brute force or as blood sport but carefully circling, approaching and re-approaching, making connections and associations that most of our brains haven’t been wired to find. Maybe it’s because she’s been paying attention to the art and culture going on around her since she moved to the city in 1976. Her latest book What Would Lynne Tillman Do?, a collection of her essays arranged from A to Z, out this month from Red Lemonade, is impossible to read without a pencil. There are simply too many sentences you want to star or underline. Through essays that cover a range of topics—from Andy Warhol to Paul and Jane Bowles; from John Waters to Gertrude Stein; from the past to the future; from a refusal to define terms like “experimental” to a lexicon of neologisms that might help in navigating our whacked-out world—I found myself underlining such choice pronouncements as, “To the star-obsessed, being known might mean not having to know yourself, and if you don’t like yourself, this must be freedom,” and “beautiful language serves—like tea, and elegant service—ironic and difficult ends.”

Tillman, who is currently working on her next novel as well as a possible “anti-memoir,” met up with me in our neighborhood over a quick dinner before she was off to meet a friend for another dinner. I saw her a few days later at a lecture on gender and psychoanalysis. By then I had the answer to the collection’s titular question. Everything. Lynne Tillman would go and see it, read it, find out about it, ask a question, take a note. We should all learn from her. Although I think she would likely hate my statue proposal, I can’t imagine anyone voting it down.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Now let’s start from the beginning—the very beginning. Where did you grow up?

LYNNE TILLMAN: Woodmere, Long Island. That’s South Shore. It’s pretty close to the city, but it’s very near the ocean and that was nice. We weren’t at the ocean, but it was maybe a 15 minute drive. You went over a bridge and then you got onto Long Beach. So summers I was either at summer camp or going to beach club.

BOLLEN: Did you go to the beach a lot as a kid?

TILLMAN: Yes. At some point I seemed to be a little fearless about the ocean, until one day, I was knocked down by a wave and swallowed the water. I was about 12. Then the ocean frightened me, but my father was a very good swimmer and even before he and my mother moved down to Florida, he would always swim past the breakers and then swim parallel to the shore.

BOLLEN: I grew up in Ohio, so I’m ill equipped for the sporting life of summer and winter. We had no mountains, so there was no skiing. We had no ocean, so no swimming past the breakers.

TILLMAN: You were landlocked. What about bowling?

BOLLEN: Yes! I think I was good at bowling for a while, and I tell people I still am, although I’m probably horrible from being so long out of practice.

TILLMAN: I like bowling. And I used to play a lot of tennis, but I couldn’t compete. One time I was in a match in camp and I was winning and people began to applaud for me, and then I started losing instantly.

BOLLEN: Was it the pressure of expectation?

TILLMAN: Well, it’s my fear of not doing well. It’s the same thing with a book.

BOLLEN: It’s almost better to be an underdog. Do you still get jittery or fearful when one of your books is about to come out?

TILLMAN: No. When my first book, Haunted Houses, came out, I didn’t know what to expect. I thought I expected nothing, and it turned out I expected everything. So I was vastly disappointed. Now, I feel pretty fortunate that I have a few readers and I’m hoping that we’ll sell more books—less so for me than for my publisher, who is my dedicated publisher.

BOLLEN: You are Richard Nash’s main writer. You’re like the house writer of Red Lemonade.

TILLMAN: I’m his only writer! [laughs]

BOLLEN: How did you end up with him?

TILLMAN: Well, you know how some people are upwardly mobile? I’m sort of downwardly mobile in the publishing world, because of my sales figures and also because of the kind of books I write. Everything really counts on sales. I started out with a bigger press, my first few books. But I’ve always done some things with independent and small presses and small magazines and I always will. So I’ve had my foot in both. For [2006’s] American Genius, A Comedy, my agent gave it to just a few people and he was one and he wanted to do it. That crazy man! Our literary marriage happened when he came to my house after he’d sent his edit, his response, which was so respectful and sensitive. We sat on the couch next to each other for seven hours, going through it. Richard is like a writer, he is a writer, who has a love for writing that is really genuine. When he’d say, “Now this word, I’m not sure—do you mean this or this?” We would have a discussion and really we could’ve been off that couch much sooner, but we just loved talking with each other about the craft—the nuts and bolts. And then, you know, he has that wonderful Irish accent, and I would rejig a sentence, let’s say, a couple of times he would say, “I’m not sure I understand,” and I completely trusted him, because he was so sensitive to what I was trying to do. Then if I would rewrite a sentence, just shift something around or use a dash—he wanted me to use some dashes—I’d ask him to read it back to me. And he read it back in this wonderful Irish accent.

BOLLEN: Did you go through this book essay by essay with him? Or since so many had been previously published, was the work more structural in nature?

TILLMAN: There were certain endings and a couple of sentences here and there that I dropped, but basically it was all done. I basically let Richard choose what essays he wanted to include. My archive was bought by the Fales Library at NYU several years ago, so they have everything on archive now.

BOLLEN: How do literary archives work for living writers? Do you keep sending stray documents and pieces to them over time, like an open-ending gathering system?

TILLMAN: They want me to do it in bulk. I guess we went about four times and they brought out boxes for us. We told them in advance what we wanted—non-fiction—so they have everything. If somebody had sent me a postcard, they’d have it filed under that person’s name. I remember saying to Richard, “Joe Brainard sent a postcard that he liked my novel Cast in Doubt—I wonder if it’s here?” and we went and there was “Brainard, Joe.”

BOLLEN: So you saved a lot of correspondence over the years.

TILLMAN: Over the years I had in my mind that I shouldn’t throw anything away and I also kept a lot of ephemera that artists had sent me. For instance, Keith Haring invited me to a party one time, and the party invitation was a jigsaw puzzle that was in a box with one of his drawings on the top. Maybe he made 500 of them, or 1,000—I don’t know if it was a big party. I think I probably went. I can’t remember. But there’s no way in hell I’d throw that out.

BOLLEN: I wonder how many there are left.

TILLMAN: I don’t know. And I was keeping a lot more stuff and early on I gave away. I donated it to [the art foundation] Franklin Furnace and Franklin Furnace gave their whole archive to the Museum of Modern Art. So some of the stuff I gave is there. I think I had the first issue of Interview magazine.

BOLLEN: When did you move into the city?

TILLMAN: ’76.

BOLLEN: You have a great essay in the book about how you don’t want to be ghettoized as part of the “East Village scene,” but how that kind of classification becomes inevitable whether there’s anything behind it or not.

TILLMAN: I think that happens more in the art world than in the literary world. I don’t think when people buy a book they think, “Oh, this person started writing in the ’90s; I don’t want anybody from the ’90s.” The literary world is more time-traveling than the art world, and novelty is much more important in art than it is in writing. I mean yes, the publishers love the fresh-faced things from Kansas, but that quickly fades—very, very quickly fades—much to the horror of the…

BOLLEN: Fresh-faced things from Kansas. [laughs]

TILLMAN: They become sour-faced very quickly.

BOLLEN: You traveled a bit before settling in New York, didn’t you? You lived in Amsterdam.

BOLLEN: Yeah, Amsterdam and London. I traveled around Europe a lot. I lived in Crete for a while, but I knew that unless I came back, I wasn’t really going to get myself together. I was floating in this world of intermediacy—in between everything.

BOLLEN: Also, when you’re travelling, it’s almost enough of a life experience and an art form in and of itself that you don’t have to force yourself to produce like you do when you come back and it’s just you and your computer.

TILLMAN: I felt I was undoing a lot of stuff that had been done to me. I’d studied English literature and American history, but the English literature, which I thought was going to be helpful to me in an immediate way, was the opposite. So I had to un-think a lot of things and move out of my own head, and I learned a lot. It was like graduate school, but an un-graduate school or an un-school.

BOLLEN: But you were communicating with writers during that time, for instance, Paul Bowles, which you have two essays in this collection on.

TILLMAN: I started to put a book together, and I corresponded with him for very pure reasons. He was the most important American abroad. I sent a letter to him to be in this book that I’d gotten money to do. That helped me recognize what the world of publishing and writing was and I was fortunate that he corresponded. I think Bowles corresponded with a lot of people, and I think he probably liked my letters to him or I don’t know what, but he was very kind to me.

BOLLEN: Those essays got me thinking about how important correspondences with great writers are to young writers—how much they can mean when you’re trying to find your way. Maybe with all of the technology it’s easier now to get in touch with other writers than it was then.

TILLMAN: I think it’s probably so much easier to get in touch with writers now. Obviously the Internet makes everything easier— you get people’s addresses and so on and everything seems much more accessible, but I also think maybe as much an influence in this is our MFA programs where our students are meeting established writers all the time. There was no such institutionalized form. I’d never have thought about writing school—I was way too insecure for that. The idea was that you go out into the world and you have adventures and you learn the way Hemingway did, or Gertrude Stein. You know, you put yourself in this…

BOLLEN: It was more of a lived experience.

TILLMAN: And you had to tough it out.

BOLLEN: I want to ask you a question about women and essay writing. It seems to me that women have excelled in the genre, making it into a literary form. I’m thinking of you, Joan Didion, Renata Adler, Susan Sontag. Without generalizing to the point of idiocy, do you think there’s something about the essay that opens itself up for women?

TILLMAN: I don’t know that I would mark it down that way. Maybe I could say this, which is probably a gender-political statement. I think those women who get themselves to write essays, it’s not an easy thing to do because as women, you’re not encouraged to think; you’re encouraged to feel. This is a broad, broad statement. So I think those women who go out on a limb and publish essays are highly conscious of how they are writing their opinions. That’s an integral part of what they’re saying and how they’re going to say it because sitting on their shoulder is an albatross that’s been telling them, “We don’t really want to hear…” I’ll tell you something. When I finished American Genius, A Comedy, one of the editors who rejected it, the only female editor to whom it was given, said about the novel, “I don’t know what Lynne is trying to teach.” I believe it’s not something she would have written to a male novelist who already had four novels out and a few other books. So the idea a writer who is a woman has something to say or is even polemical or whatever—you’re in a tougher situation, and I think those of us who’ve jumped in there are really watching our P’s and Q’s very carefully. I don’t mean holding back. I mean the opposite: going for it. You’re not going to shut me up, and I’m going to say it as best I can.

BOLLEN: How do you tend to choose your essay subjects? They range in this book on the philosophy of shit to the planting of an Allen Ginsberg tree in Tompkins Square Park. And often they come from a personal point of view. In your book of stories, 2011’s Someday This Will Be Funny, the voice is also personal; you often use a fictional narrator named Lynne Tillman. Do your fiction and non-fiction both begin with a personal response?

TILLMAN: I write about what I’m thinking about. I write about what is bothering me or what is a political, aesthetic, or ethical issue or something, and then I figure out how to do it. I don’t write essays that kind of just sustain one thought. I tend to move around because that’s what I like.

BOLLEN: Yes, in one essay you suddenly throw in a reference to an advertisement you’ve just noticed. And I think that was in the essay on Edith Wharton. It comes out of the blue, but it connects. Are you attempting to record a natural sort of thought process?

TILLMAN: I don’t know what a natural thought process is…

BOLLEN: I’m trying to have one right now.

TILLMAN: [laughs] I think I’m too indoctrinated. I’m going to use everything I can, and I think if I used an advertisement in that one, it would be yet another way to connect the current day with Wharton. Wharton has been perceived sometimes as being too upper class; Wharton was an extraordinary social thinker. As relevant today as anyone, so she uses some language that isn’t current, but to me, I’m so happy about that because I get so bored with the 100 words that people mostly use.

BOLLEN: You keep your opinions very open-ended. It would be hard to align you with a particular politics or a hard line about the state of art. For example, you don’t glorify experimental writing, whatever that is, as being more valuable than more traditional styles. You don’t necessarily privilege the novel or the new just because we are told to do that when it comes to art.

TILLMAN: I think there’s much more privileging of the new in art. I think people want to think they privilege the new in writing, but I agree with Virginia Woolf. She wrote a great essay called “Craftsmanship” about how difficult it is to use new words. It’s really hard, but you see them coming in because obviously, if you’re going to write… I mean, even to write “cell phone” in a novel —it’s so boring.

BOLLEN: I remember back in 2004, I was shocked when a book had a cell phone in it. Now that shock is gone. It would be shocking if a cell phone weren’t in a book.

TILLMAN: It’s a very curious problem—what becomes dated and what doesn’t. Things are of their time, which is different from being dated in the pejorative sense. And we learn about the time through those things, like famously The Catcher in the Rye. The clock at Grand Central Station—all those kinds of things—that’s not dated. That’s of a moment. I also think you cannot write for the future. You try to write as best you can in the moment. I think in the act of making things, that’s when we find things out. We don’t find out by following a prescribed movement or line. It just doesn’t work for me.

BOLLEN: Here’s a part I underlined in your essay on writing. “Novels and stories are not training manuals, their ‘information’ is gleaned by readers in their terms and for their own uses, often not easily comprehended in part or whole, or never.” You’re a writing professor? How do you teach writing without falling into the “training-manual” school of writing workshops?

TILLMAN: Good question. I think because I didn’t ever have any writing instruction except in grade school, writing compositions and stuff and maybe expository writing… by the way, the one essay that I wrote when I was in a junior in high school was on literary reputation. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Who did you use as examples?

TILLMAN: John Lydgate.

BOLLEN: I don’t know who that is.

TILLMAN: He was a poet who followed Chaucer. Chaucer was his master and for 200 years, he was considered greater than his master. And Lydgate, as you right now show, dropped out of sight completely and we only talk about Chaucer.

BOLLEN: How did you even know about him?

TILLMAN: I don’t know how I got it—I was a junior in high school… I have no idea. I can’t remember that, but I was already thinking about that because I think I was sort of trying to prepare myself for a very dark future, but nothing prepares you—for failure or success or what happens to most of us: some middle ground.

BOLLEN: I like how you describe writing today as doing laps outside of a pool.

TILLMAN: I think we write and not only aren’t there lanes, you’re not even in a pool. You’re flailing around somewhere, pretending to swim on the grass or something. I’ve gotten into a lot of discussions and arguments with people because I don’t take a line. I’m called all sorts of things. But I’m just trying to figure out how to write as best I can, whatever it is that I’m writing. The stories in Someday This Will Be Funny are very different from each other. Some are alike, but many are very different from each other and the essays in this book are the same—some are anecdotes, some are like the one about Edith Wharton.

BOLLEN: For fiction, is there any device you tend to lean on or use to ground your stories?

TILLMAN: I think the major device for me is that narrator’s voice. I’m always trying to find a different kind of form to tell whatever story it is, and I wish that weren’t so, because it drives me crazy.

BOLLEN: Why?

TILLMAN: Because I’m the author of my own misery.

BOLLEN: Because it’s hard to keep the voice going for so long?

TILLMAN: Because it’s hard to find that voice. Now, my character for the next novel I’m working on is a 37 year-old guy who is a cultural anthropologist and it’s contemporary, so I have to find the voice that sounds credible for him.

BOLLEN: What kind of cultural anthropologist is he?

TILLMAN: Working on family pictures. So it’s a lot about photography, which is something I’ve thought about a lot. But there’s also his family… it’s a pretty complicated story. And formally, it’s different from anything else I’ve written… But I want to go back to something we were discussing before, this question about a line: finding a line or not or being open to different kinds, because the truth is that I don’t understand it myself. I think it’s more about my taste. I also think that the issue of doubt and uncertainty is always a good thing and I question why I believe what I believe. I see things changing all around me and I don’t feel devoted to a form. If I’m devoted to anything, I’m devoted to the attempt—the “trying” to do something.

BOLLEN: I’d like to get back to the East Village question. It seems there was for a while a credible moment in the East Village when artist and writers were working together—or at least in proximity.

TILLMAN: There was collaboration, some fusion, lots of hanging out, socializing. Artists, writers, musicians. The Kitchen, then on Broome Street, encouraged collaboration, I think. New mags started, Bomb, for one. But institutions, or journals, can be very different from the people who contribute to them. The writers I was hanging out with were not being published by well-known publishers then.

BOLLEN: Who were they?

TILLMAN: Patrick McGrath, Gary Indiana, Kathy Acker.

BOLLEN: Was Dennis Cooper in that scene too?

TILLMAN: Dennis, yes, but Dennis was only in New York for two years. He was mostly in L.A. But we were friends—we became friends. And then he went to L.A., and of course now he lives in Paris. It was a loose group. It wasn’t only defined by geography, that’s for sure. And certainly I wasn’t a New Yorker writer. I’m still not. But that doesn’t really mean anything. It’s not the character of the writing, because there are some very good writers at the New Yorker. So, I don’t know how to even define these cultural camps. What I do know, what I experienced, is that when I came back from living in Europe in the late ’70s, there were films being made and there was music… I went to see The Ramones several times at CBGB. I hooked up and I lived with the same musician I live with now, a great bass player. And Franklin Furnace was going. There was Artist’s Space downtown. The economy… see, I don’t want to make it completely an economic thing, but lower Manhattan was cheaper. The city in general was cheaper. And that made a lot of things very accessible. And if you know Manhattan, you can walk from one place to another. That made it easy. If something was happening in Tribeca, I could walk home in 20 minutes.

BOLLEN: Right. For some reason that really stayed with me when you mentioned in one essay that everything was walkable, that you could always walk home and it’s so true. It really changes your idea of place when you can leave by your own two feet.

TILLMAN: That’s right. So, for better or for worse, rather than characterizing it as cohesive or this or that, that was the fact. Mostly you could just walk home. Was it a village? Who the hell knows? Galleries started opening in my neighbourhood. And they had their moments for a few years. And David Wojnarowicz and I started being friends after I met Kiki Smith in 1978. I had artist and writer friends.

BOLLEN: But you still live in the East Village today. And this book of essays has come from those decades of living here.

TILLMAN: It’s taken a lifetime. I’m about to die! [Bollen laughs] The thing is that I discovered that as I grow older, I get tougher and less afraid. You just don’t give a shit at a certain point. It’s like that line in A Touch of Evil. Marlene Dietrich has a line in that when she’s asked about the sheriff, the big fat sheriff, she said, “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter?” What does it matter what other people say. Who cares?

BOLLEN: So is it a matter of age that allows you to get to a point where you say, “Fuck it. I’m not an insecure 25-year-old anymore. I’ll do what I want.”

TILLMAN: Nothing is a matter of age. It’s really in the person because you can publish book after book after book and still want that golden apple. And maybe it’s the reality principle that has hit me. I believe that a career is very different from writing. My career is a certain kind of career.

BOLLEN: It’s an amazing career.

TILLMAN: I don’t know if it’s an amazing career. It’s been very frustrating. I don’t make any money!

BOLLEN: But who does?

TILLMAN: That’s true. Most writers don’t. So you have several jobs that you have to do before writing. And anyway, I’m rationalizing that, and that’s why when my next novel comes out, it will be many years after my last novel.

BOLLEN: When was the last novel?

TILLMAN: 2006.

BOLLEN: Now that I’ve gone through the trenches myself, I no longer understand when critics say, “their last novel was many years ago—seven years ago.” Well, it takes about seven years to write one of those damn things.

TILLMAN: I am interested in people, and I am interested enough in people that I want to be friends with a lot of people and know about their lives. So I’m not a hermit. I’m also interested in writing about other things. It goes on and on. I sometimes wish that I had a different personality. But then I would write different types of books.

BOLLEN: The essay collection is structured from A to Z. How did that ordering system come about?

TILLMAN: Richard and I played around with the idea of having rubrics, you know, “Adventurous Maiden,” I don’t know. But again, it’s much more random. I said, “Richard, A is for Andy, B is for Bowl.”

BOLLEN: The Andy piece is exceptional. I have always felt that a: A Novel is an underrated work.

TILLMAN: I’m a complete Warholian. I read every word of that book. Every word. The people who should read it are writers. Writers should read that, and they should see that they’re not imagining as big as they could. I mean, Warhol to me… You see, trying to get over your own expectations of things is an important thing to do. There are a lot of things that I read or watch because it’s comfortable, like eating baked potatoes. Whether it’s a cop show or whatever. I know everything that’s going to happen in advance and there are no surprises. But sometimes you don’t want that. Kafka wrote this great line: “my education has damaged me in ways I do not even know.” And that’s always been a signature motto for me. What has damaged me?

BOLLEN: Do you think writing is a way out of your education?

TILLMAN: I don’t think that there’s a way out of that. I, for some odd reason, write. I don’t know how or why but it was something I wanted to do from a very early age and felt I was good at. I could do this when I was eight years old. It gave me pleasure. And I still like writing. I’m not one of these people who hates writing. I hate not being able to figure out something. But once I’m writing, I love it.

BOLLEN: Colm Tóibín wrote the introduction to the book. And he reveals the very disturbing fact that you don’t like Joni Mitchell’s music. You two were on a drive somewhere and you couldn’t stand when he played it.

TILLMAN: Kill me!

BOLLEN: That’s going to be a big handicap for you in this world.

TILLMAN: I know! I know. [laughs] And I said to Colm, now that you’ve written that, you can’t tell everyone you meet that story. And I couldn’t stop him. He’s still going to tell everyone he meets that story.

BOLLEN: How long have you known him for? You seem to be close.

TILLMAN: Since 1990. But the fact that he wrote this and wrote such a serious piece, I am so fortunate, because not every friend will do that. It becomes easier and easier to say no. It used to be very hard to say no. And I wish to hell that I’d said no more to men in my 20s.

WHAT WOULD LYNNE TILLMAN DO? IS OUT NOW.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS THE EDITOR AT LARGE OF INTERVIEW MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A FICTION WRITER. HIS SECOND NOVEL, ORIENT, WILL BE RELEASED BY HARPERCOLLINS IN EARLY 2015.