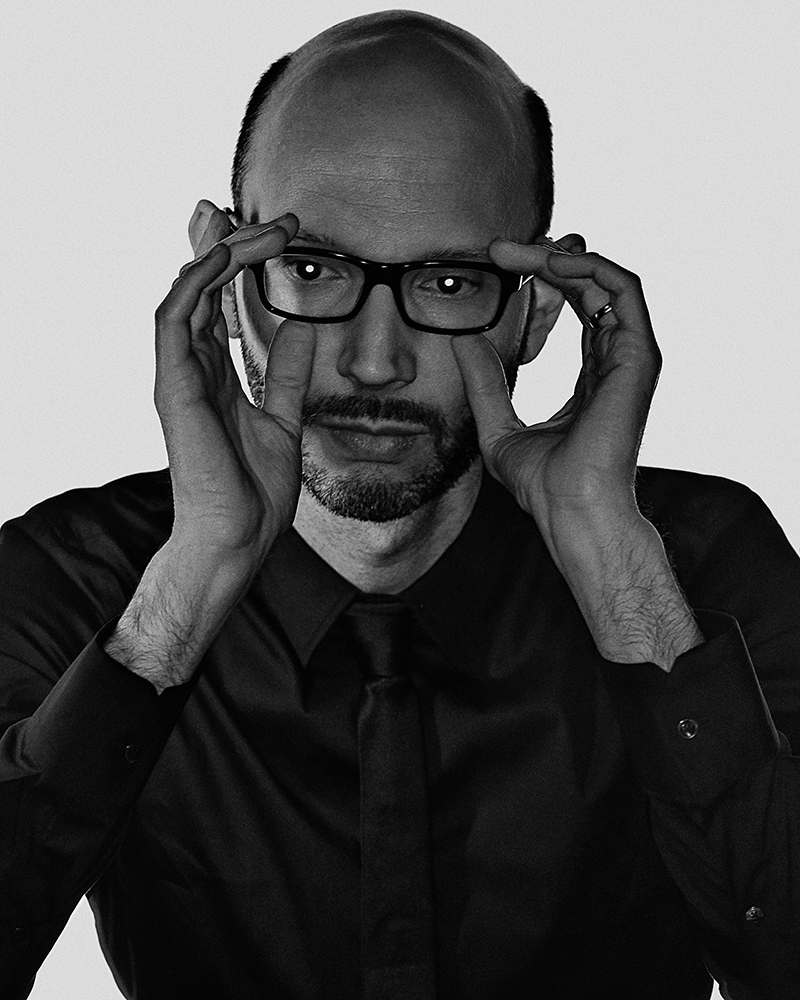

Walter Iuzzolino and the Universal Language of Drama

WALTER IUZZOLINO AT PIER 59 STUDIOS IN NEW YORK CITY, MARCH 2016. PHOTOS: DEAN PODMORE. GROOMING: MICHAEL CHUA USING DERMALOGICA AND KEVYN AUCOIN BEAUTY. SET DESIGN: COLIN LYTTON. SPECIAL THANKS: PIER 59 STUDIOS.

“All human beings tell the same stories over and over again,” says Walter Iuzzolino while visiting New York. “It’s love stories, political thrillers, costume dramas. The epicenter of narrative is the same everywhere, but we tell those stories very differently,” he continues. “The way you tell a story in Scandinavia is completely different from the way you tell it in Catalonia.”

Last month marked the U.S. launch of Walter Presents, Iuzzolino’s streaming service exclusively devoted to prestigious, foreign-language television dramas. All of the series on offer are already critical and commercial hits in their country of origin, and are handpicked by Iuzzolino himself. (He watched thousands of hours of television in preparation, and created brief, enthusiastic introductions for the shows that made it through the selection process.) Among some of Iuzzolino’s favorites are Valkyrien, a Norwegian noir about a formerly prosperous doctor and a conspiracy theorist who, together, begin a secret clinic for Norway’s underworld; Spin, a French political thriller about two rival spin doctors in the wake of the French President’s assassination; Black Widow, a Dutch drama that Iuzzolino likens to The Sopranos if, “in Episode One, Tony gets killed and his wife has to inherit the business;” and The Cleaning Lady, a South-American show about an obsessive-compulsive single mother who becomes the criminal world’s favorite murder-scene fixer.

Born and raised in Italy, and based in the U.K., in person, Iuzzolino is incredibly and infectiously passionate about his work. Before quitting his job to start Walter Presents, he had a successful career in television production. “It was very much about second-guessing the audience. You make something that’s successful, and then you make it again and again,” he says. Though his old position was much more highly paid, Iuzzolino has no regrets about leaving: “You sell your soul to the devil when you try to cynically produce stuff that will rate … There is something so powerful and intoxicating in thinking the world is my oyster.”

EMMA BROWN: Why did you move to London?

WALTER IUZZOLINO: I moved to London because I wanted to go to film school. I always wanted to do writing and directing, but my parents rightly said to me, “Get a proper degree and have a fallback.” So I stayed in Italy, studied literature, went to university, and got a PhD in American Literature in Henry James. The idea was to learn to read and understand story, and then you can do what you like. Then I did a year of translating Henry James and other Victorian writers for the theater, saving money to go to London.

I’m quite attached to my family and they are in Italy, so London was a good option; I felt like I could continue to be close to them. My first job there, whilst I was studying, was to be a script reader, which is very much linked to Walter Presents and what I do now. I was reading tons of scripts. I didn’t have much money at all and they paid me five dollars per script, so the more I read, the more I earned. I used to read about three scripts a day, and then I’d write the reports at the end of each night. It was 20 dollars for a novel. Big companies like Pathé and British Screen would receive all of these scripts from big agents and they need somebody to sift through and say to the exec, “This is good, this is not good.” I did that for a while and I really enjoyed it.

BROWN: How many of them were actually good?

IUZZOLINO: One in 100. It was better than any film school because you learn by devouring so much. You almost internalize structure; you learn what grips you and what doesn’t. You’re doing it for a living, so you have to be serious about it and you have to do a decent report. The exec will say, “Show me in one page what’s bad about this so I can turn it down to the agent.” So you read and interrogate the text; you go “This page works, it grips me. I want to go ahead,” or, “I’m now bored and I want to stop.” After uni, it was probably the biggest learning curve for me.

BROWN: Were you still thinking about writing at that time or had you moved on?

IUZZOLINO: I did it only in the sense that I was writing film criticism, never as a writer myself. If I look back with a degree of romantic perspective, I was a curator even then. I was invited to look at and oversee and curate and pick and choose and judge, which I really enjoyed.

BROWN: So what is important? What does a script need to grip you, and does it differ between film and television?

IUZZOLINO: At the same time, I was going to film school and they were teaching you creative writing for film and it was very formulaic: “This is the accident that needs to happen within the first 15 minutes. This needs to happen and that needs to happen.” We were being taught formulas. Conversely, working and reading scripts, I was unlearning that formula. There’s no such thing. Something that determines greatness in storytelling cannot be captured in a graph. So the one thing I learnt is that the beauty of the writing is essential and it needs to come from the heart. Whether you are writing an action movie or a pensive, meditative piece about two old people dying of Alzheimer’s, the core of the writing needs to start from feeling. The author needs to have something they really want to say, and then the subject matter needs to somehow create the pace and structure. There’s not that much more than that. And what makes a great novel is what makes a great film or what makes a great TV program. It is very much the same. It is not true that a script is a pile of guidelines with some dialogue in-between—even the incidental bits where they go, “Walter walks in, meets Emma, shakes her hand,” that needs to have pathos. It’s communicating to a producer, to a director, and to anyone else involved something that’s deeper than just the movement. To me, the beauty and the quality of the writing have always been essential.

BROWN: Did you grow up watching a lot of movies and television?

IUZZOLINO: Watching movies and television has always been my life—since I was three or four. My household adored cinema and TV in all shapes and sizes. My mum and dad were mostly cinema, and so with them I would go and watch beautiful, clever, interesting, sophisticated filmmaking. That’s what they taught me. Whereas at home, especially with my grandmothers, it would be more the fun, schlocky side of television. Both of them were very different characters, but quite addicted to serialized drama. My grandmother from my mother’s side was half Austrian, and a very elegant, sophisticated lady—quite academic actually. True to her roots, she liked Germanic stuff: German cop shows; tidy, structured stories. Crime and retribution, but done with style. From her, I learned what makes a good piece of television. She’d go, “Oh no, that’s bad. This is good, Walter,” and talk me through it.

My father’s mother was the complete opposite, an entirely unsophisticated, quite raucous Neapolitan woman and very visceral. She adored fake fur, fake rings. She was like a silent movie star. And she loved stories about sex and revenge and money. She loved Latin American telenovelas. There was one I’ve never forgotten called The Rich Also Weep every afternoon at 2:30, she loved it. My brother and I would sit, left and right of her, and she’d cry and laugh. It was a very dramatic spectacle. Those two sides sort of made me fall in love with the medium very much. I want to somehow be involved in telling stories. Whether it’s on the big or small screen at the time for me was immaterial. It just so happened that it migrated onto television, because I think we now live in the golden age of TV drama as opposed to cinema. What TV is doing now with binge-watching is what Dickens and Henry James and George Elliot were doing with serialized novels. Writers like Balzac and the big French writers had the same almost contractual relationship with their readers. They wrote an installment every week and it needed to end with a cliffhanger so that the following week you’d rush to the store to get the next one. I think that if these great writers were alive today they’d write Mad Men.

BROWN: Do you think cliffhangers are still important in television? You no longer have to get people to come back every week, they can just watch it all at once.

IUZZOLINO: I think cliffhangers are not what they used to be—it is not the ending with the “dun, dun, dun.” The cliffhanger, to me, is more something that happens within the body of an episode where the installment does something to you that moves your attention from A to B. Do you need to end on a [gasps]? Some do and they are fun. Some action pieces work on that basis. But overall when I read cliffhangers, [I mean] you watch a show and it shakes you into going somewhere other than where you think you were going to be. It shakes you out of your torpor so you go, “Okay, this show is alive; its heart is beating and it’s telling me to continue.” It’s about a mini electric shock that makes you want to continue on this journey, because there’s a lot of choice.

BROWN: What made you decide that there was this gap in terms of foreign drama?

IUZZOLINO: That’s pretty much been my obsession from the start. As you know, I was born and grew up in Italy, and in Italy, TV is dubbed, and dubbing is awful. Artistically, it’s actually comically bad, because it means there are six actors doing the voices of everyone. You watch a movie and whether it’s Angelina Jolie or Betty Boop, they speak with the same voice. What is, however, great about it, is that it means that language is not a barrier to the appreciation of content. A typical week on a mainstream Italian network, you’ll have a mafia local Italian show on a Monday, an American import like Desperate Housewives or Homeland on Tuesday, a German cop show on a Wednesday, and a French historical drama on a Thursday. And they’re all mainstream; you, the audience, don’t think of them as foreign, because they all speak Italian. What it means is, as a viewer, you are offered a lot of different styles and textures: different ways of photographing, different actors, different writing, different paces. It becomes really intoxicating.

Then, when I moved to London 21 years ago to do film, I was quite stunned by the lack of texture. Everything on television offered there was completely Anglo-America. They were great pieces, don’t get me wrong, but I remember thinking, “Where are the French and the German pieces that I know exist?” And I knew they existed as big, mainstream, and beautiful—they were pieces of real value and caliber. They didn’t come for a very long time, because in the U.K., and I’m sure in the U.S., subtitles were a bit of a dirty word. They were associated with niche, elitist, art house, almost opera club-type stuff—very snobbish.

I knew that that was only a part of the story, because in every country, whether it’s Germany or France, there are mainstream shows that millions of people watch. People are watching Homeland and Mad Men and Downton Abbey, but they don’t know that the same level of product is being made all over the world.

I think the old resistance to subtitles now has gone. Look at Narcos—Netflix has proven that when it comes to great mainstream success, you just need a great story, it doesn’t matter if you need to read subtitles, and I think that the relationship you develop with this type of content is more intense because there’s an extra bit of effort you have to make and it rewards you more. It’s closer to the novel. You can’t eat or cook or do something else. It’s like cinema. “This is my night in. I’m going to sit down, have a glass of wine, and I’m going to watch this French political thriller Spin.”

BROWN: Whenever I try to get my friends into some of the classic English television shows, like Blackadder, for example, they can’t get past the production value. Even though the story is great and it’s so funny, they can’t focus.

IUZZOLINO: I understand where you are coming from, [but] my answer would be that I understand [your friends]. The world has changed quite a lot; we live in an age, a golden age for drama, and you can never go back, and that means production value. When we started Walter Presents, we set up criteria, three boxes we needed to tick to acquire a program. One is that the writing, acting, directing, and visuals need to be HBO and AMC style. It doesn’t always need to be millions of dollars, but the production value needs to be crisp and amazing. If we are saying, “Watch mainstream excellence,” I’m sorry, I want to be eased into something beautiful and perfect. I don’t want imperfection.

For me, it was essential that all of the pieces we have stylistically, and in terms of grammar and pace, speak to the very best. They speak to Mad Men and Billions. If you watch something that looks a bit iffy, or is a bit slow, you’re out. You’re not going to give it time. The product needs to absolutely premium, which means that everything we have in our collection is three, four, maximum five years old, otherwise it starts to creak and you see it. Most show we have are still in production now, so it’s like watching House of Cards, Season One; it’s still absolutely perfect.

The other two criteria for us are that they need to be huge mainstream hits in their country of origin—we don’t want it to be art house, we want to speak to a broad, Billions-type audience. If 12 million Spanish people love this show, take a look at it because they’re not all idiots. There must be a reason why. Also, [we want] critical hits—we want them to be Award-winners, nationally and internationally, like Deutschland 83, which won an Emmy last year. It is important that they acquire that critical prestige so that you go in and you know that you’re safe. It’s almost like when you hear that HBO sound, you know that it may not all be for you, but it’s a guarantee of absolute quality. An audience needs to trust you, and you gain that trust by being quite severe with your selection process.

BROWN: Do you think you relate to all good-quality drama? Or are there certain genres that you just can’t get into?

IUZZOLINO: I can only answer that honestly. My taste in drama—my palette—is very, very broad, however, there are some things that I find harder. Fantasy is a genre that I have a problem with. The pieces of television that I love need to have a kitchen and a car in it; I need a taxi, not a dragon. Suspending belief beyond a certain level I find slightly difficult. For the U.K., I bought a vampire show set in Denmark in a beautiful boarding school. That is as close to crazy fantasy as I can get. It’s done as a kitchen sink, psychological drama about revenge and despair between two brothers who are cursed, so the hook in there is so strongly literary that I could completely get into it. I find overt, extreme fantasy pieces quite complicated. I’ll do Girls and Sex and the City and True Detective, so the spectrum is wide, but the flying dragon, I don’t really get.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON WALTER PRESENTS, OR TO SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERVICE, VISIT THE WALTER PRESENTS WEBSITE. YOU CAN ALSO SUBSCRIBE VIA AMAZON.