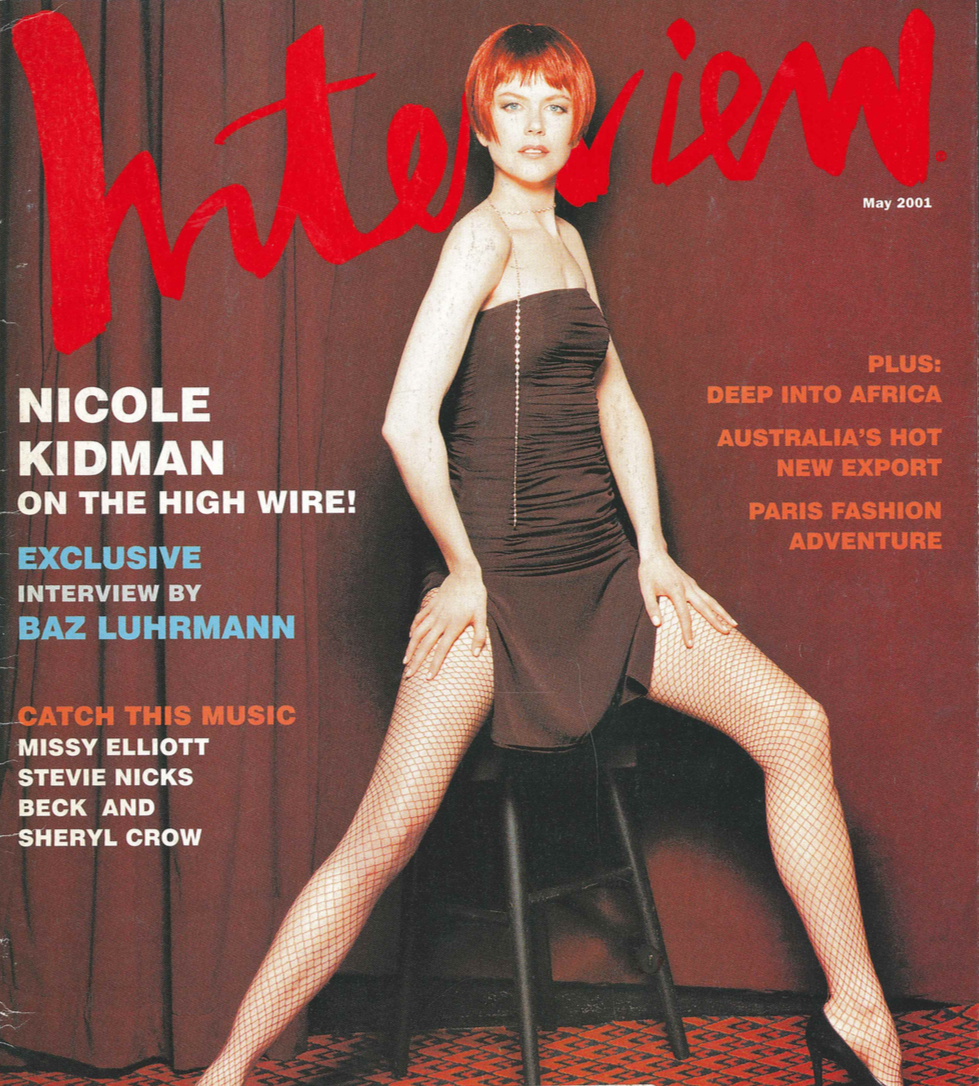

PARADIS ICONS

A Taste of Paradis: Nicole Kidman, in Conversation with Baz Luhrmann

Over its 258-year history, Hennessy has pioneered and elevated the art of cognac, a spirit fit for kings and queens. Interview Magazine hasn’t been around quite as long – just 54 years – but we like to think we, too, have curated conversations and photography that aspire to a similar level of elegance and sophistication. In honor of Hennessy’s storied Paradis marque, we poured through the Interview archives to recirculate conversations with personalities, entertainers, and icons who personify the brand’s spirit of refinement, grandeur, and artistry. Today, we revisit the May 2001 issue, in which Nicole Kidman talked to her Moulin Rouge director Baz Luhrmann about their fateful first encounter, her rigorous on-set regimen, and their late nights drinking absinthe together.

———

The Moulin Rouge. So much comes to mind—bohemian Paris, artistic expression, freedom, drama, passion . . and now the most anticipated film of the season. Baz Luhrmann’s lush, trippy modern musical starring Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor is seemingly the perfect project for the rule-breaking director, whose impressive knowledge of music, art and history is at once on display. Moulin Rouge, Luhrmann and Kidman reveal, is about extraordinary parallels between art and life; that its release coincides with a big change in the star’s personal life is striking. Here, the film’s taboo-breaking director interviews his star, friend and fellow Aussie as only he can.

BAZ LUHRMANN: [into the tape recorder] Baz Luhrmann here, at the Twentieth Century Fox lot. We’re outside the William Fox Theater and are gonna go inside and surprise Nicole Kidman. She has absolutely no idea that we’re about to expose the truth behind the Kidman story. [to Kidman] Hello. Nicole. I’m doing a hard-hitting interview for Interview magazine. So, what’s it like? [laughs, addressing her dog] Well, shih tzu, how is it?

NICOLE KIDMAN: That’s Moulin! That’s Moulin, and now we need a Rouge.

BL: Thank goodness we weren’t doing a film with a long name in it!

NK: So, don’t you like my dog?

BL: Absolutely. Gorgeous. Cute.

NK: Very sweet. And passive. Just like me.

BL: Give it time. OK, I’m trying to do my hard-hitting interview here, right?

NK: Can you hear me from over here?

BL: Don’t worry– I’ll come over there. I’m a professional, and this is my hard-hitting interview for Interview magazine. So, I think it’s important we don’t talk about me at all.

NK: But I’d prefer to talk about you.

BL: So, when did you first work with me? [both laugh] And what was it like?

NK: [laughs, feigning Luhrmann’s voice] “And how do you feel about Baz Luhrmann?” [laughs]

BL: Let’s talk about the first time we met.

NK: The first time was on a photo shoot, right?

BL: We were guest-editing a magazine.

NK: An Australian magazine.

BL: Right. I don’t think I’d ever spoken to you before, but I remember distinctly being very aware of you, right, and always fascinated with what you were doing. So I met you at the Four Seasons Hotel, and I remember my first impression of you was how Australian you were, and you had this really, really loud hacking laugh.

NK: Oh, that’s charming! I thought you were going to say something really flattering. And instead…[laughs]

BL: And actually. I think that’s what’s in the film. I really do. I think that my first image of you which was so not what I expected, is to the film. Cause you have such a refined, such a very…iconic imagery–that’s just the way it is. God put that one on your shoulders and you can’t shake it off. But when I met you, you were like so many of the girls I knew growing up. So crazy, so noisy. I say noisy because I remember you were eating along and suddenly “Yahh!”—you let out a big scream. We made quite a bit of a noise in that restaurant. I can’t remember if they threw us out, but I think they wanted to.

NK: And then we did the photo shoot. It was so much fun. And I remember thinking, Oh God, I’d love to work with him, but he’ll never wanna work with me.

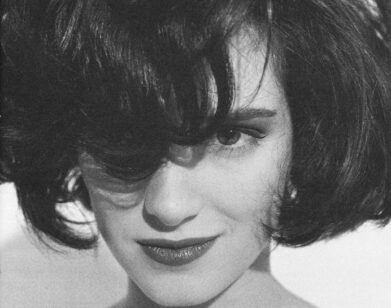

BL: No. no, no. I can remember doing that shoot and thinking, There’s a whole side to you that the world has absolutely no idea about—that you are funny. Remember the Lucile Ball stuff we did?

NK: Yeah, we did the dancing with the dummy.

BI: That’s right, and it was also—

NK: And you were dancing around too, off camera.

BL: I was not!

NK: [laughs] Yes, you were!

BL: I’m very serious when I work. [laughs]. Very serious and very focused. I was demonstrating the dance move, if I remember.

NK: [feigning Luhrmann’s voice] “And more, and more, and bigger and big” [laughs] That was great fun. But my other vivid memory of you was the audition process for this film.

BL: Yeah? Tell me about that.

NK: The first thing you said to me was that after the Australian magazine thing came out, I never called you about it.

BL: Well, actually, you didn’t!

NK: I did! I’m very shy, though.

BL: Bullshit! Strike that from the interview! It’s my interview, and l’m not having that bullshit in my interview, right?

NK: It’s true! It’s why I couldn’t call. I’m too shy!

BL: But you did do something else. I think I got a Christmas card from you. So I understood that you were—

NK: Did everybody else call?

BL: It doesn’t matter; it didn’t concern me at all.

NK: [laughs] It obviously did!

BL: It was only that we worked non-stop, you know, making the best possible images. You think I was hurt? No, no, not at all.

NK: [laughs] That’s awful! I can’t believe that I didn’t call. Let’s talk about you and your opera.

BL: No– I want to tell you something. For years you were doing very serious roles, like The Portrait of a Lady [1996]. And I remember thinking, God, one day someone’s gotta release that incredible vitality and that crazy comic energy of yours into a film.

NK: I was begging for it! I was so sick of playing the serious sort of roles. But now I feel I can go back to them. Though once you’re hooked, you’re hooked.

BL: [speaking into mike] Not too quickly, folks. Right?

NK: [laughs]

BL: Let’s just get some logical storytelling here for the interview. Now I set out to do Moulin Rouge, originally, with young kids in the lead roles of Satine and Christian, and… well, Christian was always young.

NK: Oh, thanks Baz.

BL: [laughs] I meant—

NK: Cut to the chase! You ended up casting me, the old pauper. [laughs]

BL: I wanted people in their thirties. Young people. Then I realized, one of the great old dames of the theater could play Satine. And lo and behold, you were on Broadway!

NK: [gasps] You’re cruel! I’II never forget, on the set you used to say, “Come on, you old hoofer!*

BL: No I didn’t, that is not true.

NK: I swear to God! You said, “Come on, you old hoofer! Show us what you’re made of!” [laughs]

BL: I never said that! Well, I did call you an old hoofer, but you really manifest the same characteristics as one of the old hoofers.

NK: [laughs] Fantastic!

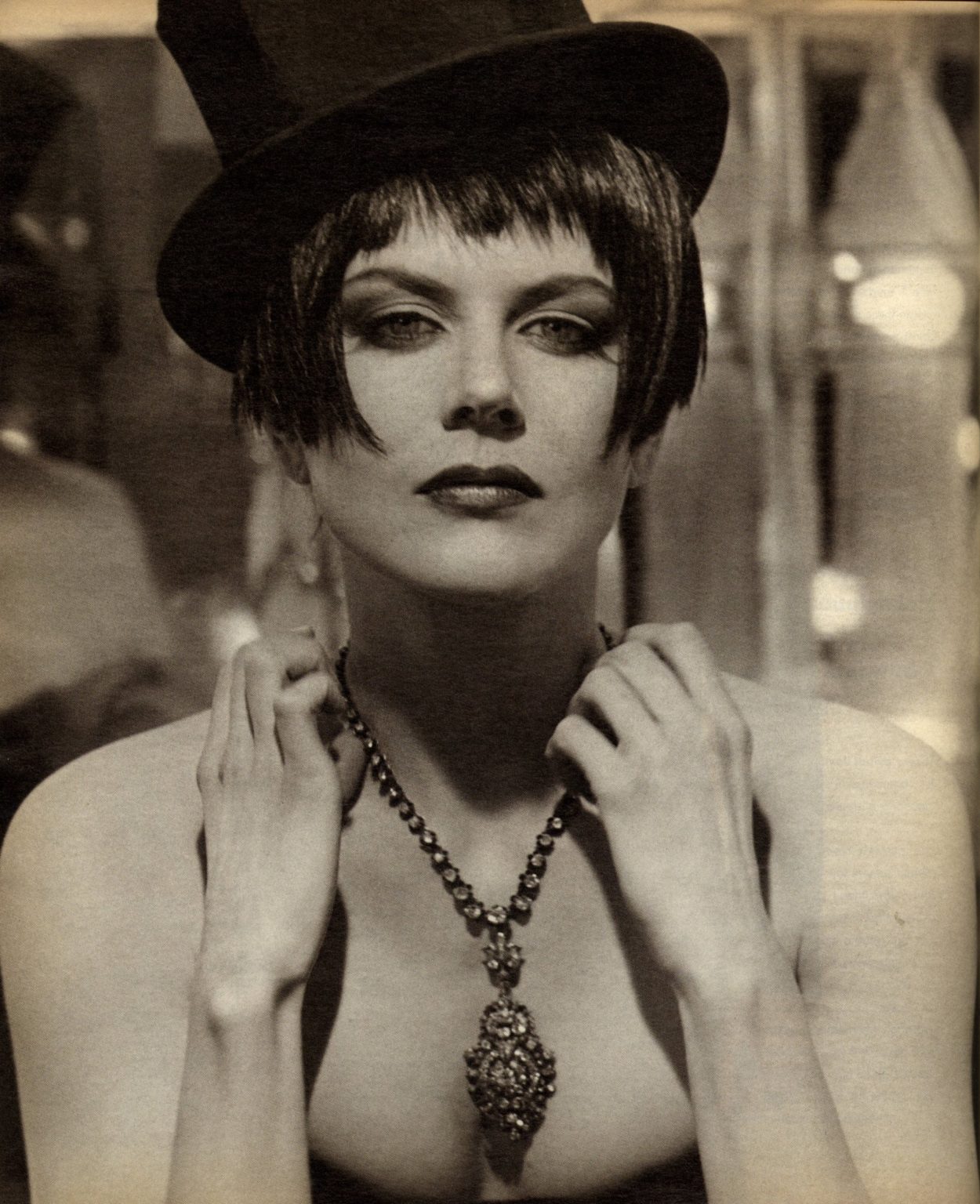

BL: There is a bit of that old Hollywood showbiz quality about you. To me you embody a lot of those classical, iconic Hollywood movie stars of the 40s and ’50s. Now that was a crucial element in making this film because we wanted to reference that. We made the decision that Satine should have the iconic maturity of a Lady Di. That she was a woman at her absolute sexual prime. Or like Madonna. She was one of these really iconic characters.

NK: Right.

BL: Someone at the peak of her powers, and she fell in love with, if you like, a virginal young man, a young man who was very new to the act of love. And she was trying to get back to, you know, virginal pure love. But that was the whole rebirth of the story, of her character’s journey.

NK: That’s what I liked. The arc. You have him becoming worldly, and her learning to love again.

BL: Do you remember how I made contact with you? You were on Broadway in The Blue Room [1999], and I couldn’t get in the stage door for the thronging crowds—this is a fact, folks: there were maybe 200 people at the stage door.

NK: Oh, they were so good to me, the audiences there. But you came back and saw a preview.

BL: That’s right.

NK: Not cool to see a preview, I must say.

BL: It was remarkable.

NK: Yeah, but you don’t come to the previews! [laughs] You sent me red roses the next day, backstage. Which was really lovely. And the note said, “Loved the performance, loved the play, blah, blah, blah.”

BL: It didn’t say that at all!

NK: No, no, no, you wrote, “I have a role. She sings, she dances, dot-dot-dot, and she dies.”

BL: Well, how could you refuse?!

NK: But that was really confusing, ’cause it was like, “Oh gosh, does that mean he’s offering me the role? Or does that mean now I have to go on 25 auditions?” It was the latter! [laughs]

BL: Let me explain that.

NK: Next time you write a note like that, make sure to put, “And I’d like you to audition for it.”

BL: Oh, that’s right! Wring out the dirty laundry! When I think how absolutely supportive I was during the whole process! Well, we had to investigate the issue of singing, and it’s not like an actor would pick up the phone saying, “I am such an incredible singer, give me the role!” Actually, there were a few who did, but we won’t go into that.

NK: And I dare say, I did not sell myself as a singer. I kept saying, “Oh, Baz, I don’t know about the singing…”

BL: The important issue was that it was about actors who could sing.

NK: That’s right, you kept saying. “I want an actor who can sing.” And I’d say, “Look, I’m not Whitney.”

BL: Yes. but certain people were chasing you to do Chicago, the film. Which certain people were chasing me for as well, but we won’t go into that, either.

NK: That was after the play, too.

BL: That’s right, and there was a time when I thought I might lose you to Chicago.

NK: Yeah. And Madonna was gonna do it [Chicago] as well. That was exactly the same time as Moulin Rouge.

BL: And you chose Moulin Rouge. The gig, at least. But what the people should understand is that we had to explore your singing, but the other thing was finding a Christian. I was aware of Ewan [McGregor]. but Ewan was doing a play in the West End.

NK: Mm-hmm.

BL: And then I found a way of getting to him. The interesting bit about that was that he was onstage in the West End doing one fantastic play, and you were onstage on Broadway doing another, so you were both, as far I was concerned, stage actors. So I was feeling very secure about these two people doing a musical.

NK: Right. And wan and I both came off the plays and came to your workshop in Australia each having finished this great creative experience.

BL: Talk about that, ’cause it was an extraordinarily long period of development.

NK: Your process—as an actor—it’s the perfect process to work in. Because by the time–

BL: No, no, no, Nicole! I wrote here very clearly, “Yours is the greatest process l’ve ever worked with, and you are—”

NK: “The greatest director in the world.” [laughs]

BL: Let’s go back to the top. Pick it up from “You are the greatest.”

NK: [laughs] Your process is shite! [laughs] No, really, your process is great because as an actor you come in and you’re given a very distinct character. So you walk into it and suddenly you told us we’re gonna spend two weeks doing a little singing, a little improvising, a little dancing. And everybody there is so excited– if only everybody worked like that.

BL: We did a lot of work, but we also had–

NK: Fun! Great fun. We had those incredible dinners, drinking wine and absinthe.

BL: Ah, the absinthe. What exactly happened? Mind you, this is not one of those namby-pamby interviews where we skirt around the point! So what happened with the absinthe? Do you remember at all?

NK: I remember flames, I remember lighting the absinthe, but I don’t remember much else. No, wait–I remember dancing wildly at one stage. On the chair, on the table. And watching videos.

BL: That’s right! You know, Nicole, the extraordinary thing is the parallel between the film and all of our lives. I mean to a harrowing extent. The profound amount of tragedy . . . the characters in the film, their needs and their wants and their drives—

NK: I think that’s because we spent so long doing what you cast us to do, and at the right time. I was so ready to do a love story, but then all those tragic elements that came in, in terms of dying and the layers not that I died, but in terms of just going through it all, the emotional weight of that, by the end, was just so powerful. I’ve never been so exhausted, yet so satiated at the same time. Creatively. I didn’t want to make a movie again after I’d finished this one.

BL: The story, as you know, is based on the Orpheus myth, and that myth is about ideal love. Christian looking for and finding what he believes is the ideal love. But, at the end he loses that love and he goes back up into the adult world, if you like. And I used to say this ad nauseum: People will die, time will pass, things will change and there are some loves that…

NK: …Could not be.

BL: Could not be. You and I are both on that level of experience. You know, my father died on the first day of shooting, which now I’m very at peace with. But it was quite a moment, wasn’t it? Dad was sick and we knew he was going to die at some point, but I was having a sort of out-of-body experience setting up the very first shot. I’m not trying to draw attention to my own tragedy, but if you think of that, with yourself and your own relationship–

NK: I spoke to you directly after all the things that have happened in my life in the last few months, and you said, “It’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.”

BL: And that is the whole point of the film really, isn’t it?

NK: Mm-hmm.

BL: Every one of us had some realization that no matter who you are, no matter how many gifts you have, how lucky you are, there are things greater than yourself. And they change. Things will change, and there are some relationships that–

NK: For whatever reason will not be forever.

BL: And you take that with you, and what I hope you get out of this film, is that when you lose that naive, youthful idealism, you don’t become gun-shy of romanticism or idealism. It’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. It’s an adult moment. Whereas when you’re young, the Romeo and Juliet myth is that love will last forever, come what may, no matter what.

NK: Yeah. [pause] Wow.

BL: Our lives, and that film, have been so mythically linked!

NK: [whispers] I know! [pause] I’ve never had that. I’ve never had a film affect me so . .. And I’ve worked on pretty strange films [laughs]—Eyes Wide Shut [1999] and The Portrait of a Lady but there was a purity attached to this. Everyone came into it with the belief– the young poets’ belief.

BL: I think you’re right. A dangerously naive commitment to risk. Remember Tom, when you showed him the first footage, he said, “My God, the ambition in this film.”

NK: Yes. I remember.

BL: And what he was saying really clearly was, “The risk in this film.” And you know, no one shied away from that.

NK: I never doubted it.

BL: I know what you mean. There are two themes that we pursued all our way through it. One is the Orpheus myth. The other one is “the show must go on.”

NK: Mm-hmm.

BL: And that led me to another parallel– the film is about a circus family. And what I mean by that is that when you make a story or perform or convey a myth to the public, you are a whole bunch of desperate people who are really highly strung and weird and strange and all of those things—but all of them have gifts. All these people are brought together, usually in a physical place we don’t live in…

NK: Huh?

BL: Well, we all lived out of vans, right?

NK: Right.

BL: And we’d go into a shed– a tent– to film, right? Where basically there’s a guy in charge, a ringmaster, and there’s a high-wire act, you know a story that’s created that’s kinda higher than life.

NK: Yes! Yes, Baz!

BL: I guess I’m bringing up that image because one of my memories of the circus theme was that you lived in a van. You’d go there and the kids would be there and there you are, getting your wire act ready.

NK: Yeah, my dad said one of the best images he had was when he came to visit on the set and I’m in the van, cooking dinner for the kids in four-inch stilettos, a corset, fishnet stockings, long red hair and a top hat. And the kids didn’t seem to think there was anything strange about it. And I didn’t seem to think that there was anything strange about it either.

BL: That’s it! How like a circus is that?

NK: Totally. But everybody just takes these very bizarre circumstances as the norm.

BL: ‘Cause they are the norm.

NK: The norm for us.

BL: Describe your day shooting Moulin.

NK: I got up at five and did a little yoga, and then a 20-minute dance warm up. Then, at about six, I’d go into the makeup chair for an hour and a half, then the hair chair for another hour and a half. So you’re looking at three hours before you’ve even got to the set. Then you go into the trailer and get harnessed into this corset, which takes 20 minutes. And then you gotta go act, do the work. I suppose to some people that doesn’t sound all that difficult but the work that it takes to do a musical, I mean, it’s phenomenal.

BL: It’s why people don’t do them.

NK: Thank you for telling me now. [laughs]

BL: But, here’s my question—you low, I watched an episode of Oprah the other day, just to bone up for this interview—

NK: I saw Bill Maher the other night and he said that Oprah has made the whole world revolve around making women nod.

BL: What do you think of that?

NK: Sexist comment, but interesting. Everything has to be moving, so women applaud then nod.

BL: Mm-hmm. Can I nod?

NK: Yeah. [laughs]

BL: Anyway, my Oprah question was this: What you haven’t mentioned in your day’s work, are all of your other careers. That’s what I mean by the circus thing.

NK: Like what?

BL: The kids, your life, you know, dealing with all of that—it’s just ingrained. It’s invisible to you. You didn’t bring it up because it’s invisible. They’re there in the trailer: they’re there on the set. It’s just life.

NK: Yeah. I would go back in after doing takes to make sure the homework was being done. [laughs] Then suddenly I’d be doing grade one reading for 20 minutes, and then back on the set. And for their math lesson, they’d be out betting with the crew. Playing poker [laughs]—now that’s how to do mathematics!

BL: That’s reality—your circus reality.

NK: I remember finishing the film being more exhausted than I’ve ever been in my life. We were working really long hours to get the film made in the amount of time and with the amount of money that we had to do it. I was pushing myself beyond what I’d probably be willing to ever do again because it was so much fun and because we believed in it.

BL: Well, isn’t that like what we were talking about earlier, about risk? It’s a ridiculously scary, risky thing to ask an actor to go out there. And when I said that the film and our lives are the same, that they were a high-wire act, I didn’t mention that you actually do a high-wire act in the film.

NK: Yeah. That’s right. I remember becoming just so at ease up there.

BL: That’s what I mean! You’re so blasé. You didn’t mention the fact that you were actually up on a trapeze, that you had to be trained by circus people to get up there.

NK: Oh, but I love that stuff.

BL: And I’m going, “No, I’ll have the double and you’re like, “I don’t think so.”

NK: But I’m not frightened of heights. Anyway, we won’t go there. So then what are you going to go into now?

BL: We’re looking at doing a number on Broadway at the end of the year.

NK: Yeah!

BL: And you?

NK: I’m looking at a few things. You know what I love, though? I love working with directors that have a particular style. That’s what’s interesting—when you really work with directors who are known for a point of view. Like at the moment I’m exploring something with Lars von Trier, who also has his particular—

BL: Cinematic language.

NK: Yeah, I find that very stimulating. The more controversial it is, the better.

BL: The really simple view is that, and this is no judgment, but essentially, there are storytelling filmmakers—Scorsese, Lars—that no matter what the subject matter, they have a language. You know it’s their work. And then there are shooters, these people who are amazing craftspeople who go out and tell very good stories amazingly well. But you can’t tell that they’ve made that film, it’s just a well-made film, you know? I think it’s a bit like authorship to a certain degree.

NK: Yeah, it’s true. Toni Morrison is one of my favorite writers because she has such a distinct voice nobody else could write like her.

BL: [into the tape recorder] See how cleverly she’s reflected it back on the need to avoid asking hard-hitting questions? [laughs] But seriously, I think one must evolve one’s language. Not only what you say, but how you say it, has to evolve specific to the time and place you’re in your life.

NK: That brings us back to the theme of the movie, which is to evolve.

BL: That’s right. That is the point of the film. You and I know, the one thing about the Orpheus myth is that once you’ve been around the world, stayed at the groovy hotels, done all those things, then what do you do? Do you just go and do them all again? And where is the next level? Where do you go? What about you, Nicole? Where are you now, and where, really, is the next level for you?

NK: That’s something that plagues me. I’m constantly saying to myself, “All right, so this is my life now, but where is it going to lead me that’s going to make me a more fully realized person?” Because you can settle into complacency and that terrifies me.

BL: Yeah, and I think you can settle more easily in our environment than in others.

NK: Yes. When you’ve reached a certain level you go, “I don’t need to push myself, don’t need to challenge myself.” Success, I think, is something so corrupting to us all.

BL: Is it that it brings power?

NK: It brings power, it brings complacency. I think as an actor, as a director, as a writer, as an artist, there is no formula. It’s about saying “OK, I’m willing to take a risk and I don’t care if I loose everything, because what is all this worth If I don’t have my integrity and free spirit?” I suppose it comes back to being free-spirited.

BL: What do you mean by that, Nicole?

NK: Well, it means not being controlled, not being confined by expectations of others. Or even your expectations of yourself. And it’s hard– it’s very easy to say and it’s much harder to do.

BL: So how do you do it?

NK: I’m trying to find out. I think by always challenging yourself and not slipping into what is expected. And when you read something, not judging it based on your past experiences but really trying to accept it for what it is, here and now.

BL: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

NK: You can’t say, “OK, here’s a scene. Well, that’s easy for me. I know exactly how to play it. I’ve got references from my past work; I’d play it this way because I’d seen that movie.” No, you have to take it for what it is and try to make it as real and as instinctual as possible at this moment and time. That’s how you get exciting work.

BL: You just get thrown into the moment. And without that free spirit, without the freeing of your spirit in acting you’re dead, you know?

NK: Dead because you’re playing what you already know, and what’s interesting is what you don’t know, and it’s not necessarily what you expect, what you planned or what you hoped for.

BL: Yeah. We should nod our heads now.

NK: We’re both nodding. The Oprah nod. [both laugh]