Sheila Heti’s Hysterical Realism

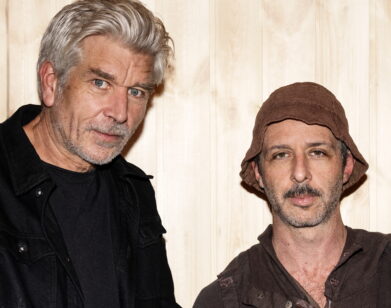

PHOTO COURTESY OF SYLVIA PLACHY

Female coming of age provides an endless wellspring for artists to draw from and critics to debate—most recently spurred and exhausted by HBO’s Girls. It is the ideal climate for Sheila Heti’s fifth book, How Should A Person Be? to be released in the United States. It’s drawn praise from everyone from The New Yorker‘s James Wood to, well, Girls‘ Lena Dunham herself.

Despite its title, Heti’s autobiographical novel doesn’t attempt to provide any definitive answers of how any one thing “should be”—but it is enlightening, profoundly intelligent, and charming to read. Part memoir, part fiction, it plays with the idea of ecstatic truths in exploring reality-documentary conventions, and it includes transcribed conversations and personal emails as well as prose. It reflects life in its incredible humor—and in some of its weird bits that might be muddled or unclear. The main character, Sheila, deals with her self-doubt, her ambitions as a playwright, and figures out platonic friendships as well as a dominating sexual one—all the while trying make sense of her experience, with anxiety, hilarity, and lots of great conversation.

JACKIE LINTON: As someone who does a lot of interviews yourself, you’ve said that you don’t particularly like to interview authors, since the books at hand are always self-evident, and the questions can seem very obvious. With your book, How Should A Person Be?, the message is very clear in the experiences you share, even though you don’t try to directly answer some of the questions in the book.

SHEILA HETI: Yeah, there are already answers in it, and I think for me, I would rather come up with other questions. I don’t think the right answer would be to say how a person should be. I think when I started I thought I would come up with this idea of one Platonic person—but everyone seemed so great to me in their own way, like Misha seemed great to me for these reasons, and Margaux for these different reasons. I wanted to be like everyone, and it’s hard to see oneself at the same time.

LINTON: Was it hard to see the book when you were writing it? You went back through many years of your life, you included emails and recorded conversations, and you included so much of your friends.

HETI: The gestation of this book is much longer than my other books, like Ticknor or The Middle Stories. I went back to being a teenager when I started to think about sex, and feminism, and friendship—just a larger span of my being for this book. Which is wild—I don’t think I’ve had that experience before, covering so much time. It’s a pretty wild feeling—and I didn’t mean to do that, but it just happened incrementally, day by day. If something came to me, I wrote about it. I didn’t think I was writing a memoir, necessarily.

And it’s just such an intimate part of your life when you’re writing any book—I mean, you just have every possible thought you could possibly have, and every single feeling you could possibly have. You think you’re writing the most important book, you think you’re writing the most stupid book, and you never really know before it’s done that it’s going to be done. But when it was finished, I wanted it to have nothing that could be added or taken away from it—and be able to see it as a whole. But I also wanted it to be loose and painterly, and like life. Which is why you don’t necessarily know why some parts are there.

LINTON: The idea that James Wood put forward in his review of the book, that the writer seeking life, trying to write from life, is always unappeased since the manuscript can ever “real enough”—do you find this is true?

HETI: I had no idea what he meant by that—it didn’t really make sense to me. You’re trying to make a work of art, you know? You’re not trying to make it “real,” you’re trying to make it great. [laughs] I never had the feeling that it wasn’t “real.” You’re trying to make it work, and make it beautiful. And I wanted it to be like life, in the sense that every writers want their work to be about life, but the book is not ‘life”…

LINTON: Which would be impossible, and while the book title does include A Novel From Life, it is not suggesting a novel from real life or complete reality…

HETI: I mean, I get this question all the time, “What’s the difference between you and the character?” and it’s like, I’m a person and not a piece of paper. [laughs] How can you even begin that question? It’s just so weird. A person is not a static thing, or a bunch of words. The book doesn’t seem like realism to me. If you want to write from life, you can’t really write a story. People are always changing, and I think if we didn’t look the same day-to-day, and our self weren’t always in our body, would we even be the same? The continuity is in our bodies. So it’s hard in literature with characters. You don’t have that body. The character is always less than human.

LINTON: You were also very interested in reality television—and Werner Herzog films. The idea that fiction would be mixing in with these depictions of real things happening in stories.

HETI: Those things excited me because I didn’t understand the rules. On the first season of The Hills, it was really weird—I mean, by the end it just became silly. But I hadn’t seen anything like it, and I didn’t understand what was going on. [laughs] And in the book, I wanted to create that feeling. It’s a more exciting feeling. And that idea of the “ecstatic truth,” in the idea that documentary is going after truth, but that you also need to take liberties.

LINTON: Yeah, the dynamics are all very relatable. It could be that Canadians are naturally self-effacing, but I can certainly relate to how funny the book is about a lot of things, even though it is very serious at the same time. Especially funny about wanting to be taken seriously. And just because it’s funny, doesn’t mean that seriousness isn’t there.

HETI: Yeah totally, definitely. We have this conversation in the book about how the best artists are funny. And I think it’s true, if I’m reading a book, and it’s not funny, I seriously have doubts as to whether it could be a great piece of literature, because a huge part of life is that it’s funny. In many ways, it’s the only redeeming thing about life.

HOW SHOULD A PERSON BE? IS OUT NOW.