Scott McClanahan Tells It from the Mountains

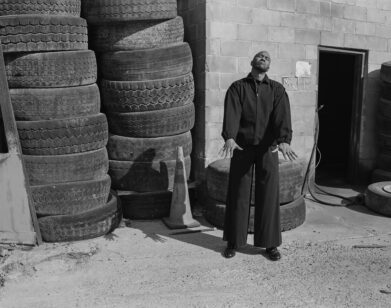

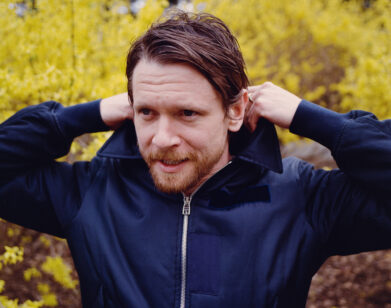

ABOVE: SCOTT MCCLANAHAN. IMAGE COURTESY OF SARAH MCCLANAHAN

Scott McClanahan’s Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place (Two Dollar Radio) is a raucous remembrance of the author’s redneck youth. McClanahan recalls with vivid hilarity and heartbreak his grandma Ruby, with her fetish for taking photos next to open caskets at funerals, and his uncle Nathan, who suffered from cerebral palsy, loved watching Walker, Texas Ranger and had an undying passion for his home health aide. Growing up in rural West Virginia, McClanahan grapples with ghosts, growing pains, prank phone calls, insanity, forlorn love, and sex. Part memoir, part hillbilly history, part dream, McClanahan embraces humanity with all its grit, writing tenderly of criminals and outcasts, family and the blood ties that bind us (even when they embarrass us by soiling themselves in a chain restaurant). McClanahan’s childhood haunts him, and haunts readers, too, but beautifully so. We caught McClanahan in New York and downed cheap 40-ounce beers on a Lower East Side roof while discussing cerebral palsy, fried baloney, seduction, Oscar Wilde, what his grandmother taught him, and the truth behind tall tales.

ROYAL YOUNG: Let’s talk feeding tubes and pouring beer through them into your stomach.

SCOTT MCCLANAHAN: That’s what you do for your homies [laughs].

YOUNG: [laughs] That never actually happened, right?

MCCLANAHAN: No, it didn’t. My uncle Nathan would always talk about it. That was his thing.

YOUNG: Where did the tube actually go?

MCCLANAHAN: He had what I think what they call a punch tube, which was this direct mainline into the stomach. They would put this rubber catheter-type device on and just pour shit in.

YOUNG: Was it like an open wound?

MCCLANAHAN: Yeah, and you would bandage over it between feedings. It kind of healed around the tube. He could eat, but it was really the psychology of his mother, and I think with hospitals and “docturds,” d-o-c-t-u-r-d-s, in general the philosophy is if you’re not doing something, you’re not helping at all, because he was a 40 year-old man with cerebral palsy. Especially in West Virginia, with Medicare and Medicaid, if you can bill somebody, you do it. There’s no reason for it. He was embarrassed by it.

YOUNG: Was he embarrassed by his condition in general?

MCCLANAHAN: No, I don’t think so.

YOUNG: Good.

MCCLANAHAN: I don’t think he fit into any category. He always sat at the head of the table. Conversations always revolved around him. So I’m sure there was knowledge that he was different from the rest of his brothers.

YOUNG: As a kid, what was it like being around that?

MCCLANAHAN: One of my first memories is practicing my ABCs, sitting in the corner of the kitchen, and being afraid of him. Going through them and thinking he was some kind of monster eating fried baloney. I’ve never been able to eat fried baloney since, not that I was a big fried baloney consumer beforehand. I’ve always connected it to that primal fear. What was scary is that he was hyper-intelligent, but trapped within this flesh. He was a neat-ass dude.

YOUNG: When did you go from being petrified to thinking he was a neat-ass dude?

MCCLANAHAN: I remember how he would pet kittens, and because his hands didn’t work, there was something violent about it, but at the same time, it was so soft. Softer than a typical person. There was something sort of seductive about his personality. People were drawn to him and saw different sides of him. He was trapped by his body, his mother, his environment; but there was also a freedom in him.

YOUNG: You had such a close relationship with your grandmother. Can we talk about the beauty in that?

MCCLANAHAN: Well, there was a lot of tension between my dad and his mother and brothers. Sometimes when I was over there, I remember thinking, “I don’t want to get shot.”

YOUNG: Did they all have guns?

MCCLANAHAN: Well, they’re rednecks.

YOUNG: I’m a Jew from New York, so you have to educate me about it.

MCCLANAHAN: Yeah, it’s like shotguns and rifles for shooting small game, large game, or your wife. No not one of them ever shot one of their wives [laughs].

YOUNG: But you viewed your grandmother so differently than that. You got a lot of wisdom from her, maybe inappropriate truths.

MCCLANAHAN: Yeah, my grandmother just made up stories. You know they didn’t really happen. I’m shocked and surprised by people that are shocked and surprised that certain things in life are made up or not as true as you might believe them to be.

YOUNG: Well, everyone has myths about their lives; you find a story your life can fit into, and you tell it that way.

MCCLANAHAN: Yes, and in memoir, can you really tell the truth about yourself? You’re not going to write about your little peccadilloes, like, “I like a finger in my ass during sex.” Or whatever it is. You’re not going to come out in typical everyday conversation and say that. That’s something that’s going to be only for a select few.

YOUNG: Though I feel like there’s some quote I’m going to fuck up: “Give a man a mask and you will see his true face.”

MCCLANAHAN: Oh yeah, that’s Oscar Wilde, that’s Bowie, that’s Dylan.

YOUNG: So in the telling of a story, you’re telling a truth that’s truer than if it was recorded on video and you got the play-by-play of “real events.”

MCCLANAHAN: I agree. For instance, we had pigs out behind the house when I was young. People think of pigs as these cute or delicious creatures. But hogs have huge fucking testicles, and they’re mean as shit. They’ll knock you over, trample you to death, and eat your corpse. They have no problem with that. And their brains are like human brains; isn’t that what people do? Doesn’t that feel like Manhattan?

YOUNG: I did that yesterday!

MCCLANAHAN: My grandmother taught me that. She was very fatalistic. She collected photos of dead people, the hogs, Nathan. I feel so damn far away from that stuff now, Royal. And I almost feel like I’ve betrayed them.

YOUNG: By writing about them?

MCCLANAHAN: Not just writing about them, but living the life I live now. Sitting on top of a roof in New York telling these stories about them. They didn’t have to do that.

YOUNG: But when you say betray, that means to me that they would be somehow hurt and unhappy with what you’re doing. I don’t think that’s the case.

MCCLANAHAN: Yes, but the stories that were important to them aren’t the ones that are written down, they are the ones you tell or make up or tell throughout the day just to your family.

CRAPALACHIA: A BIOGRAPHY OF A PLACE IS OUT NOW.