Q&A

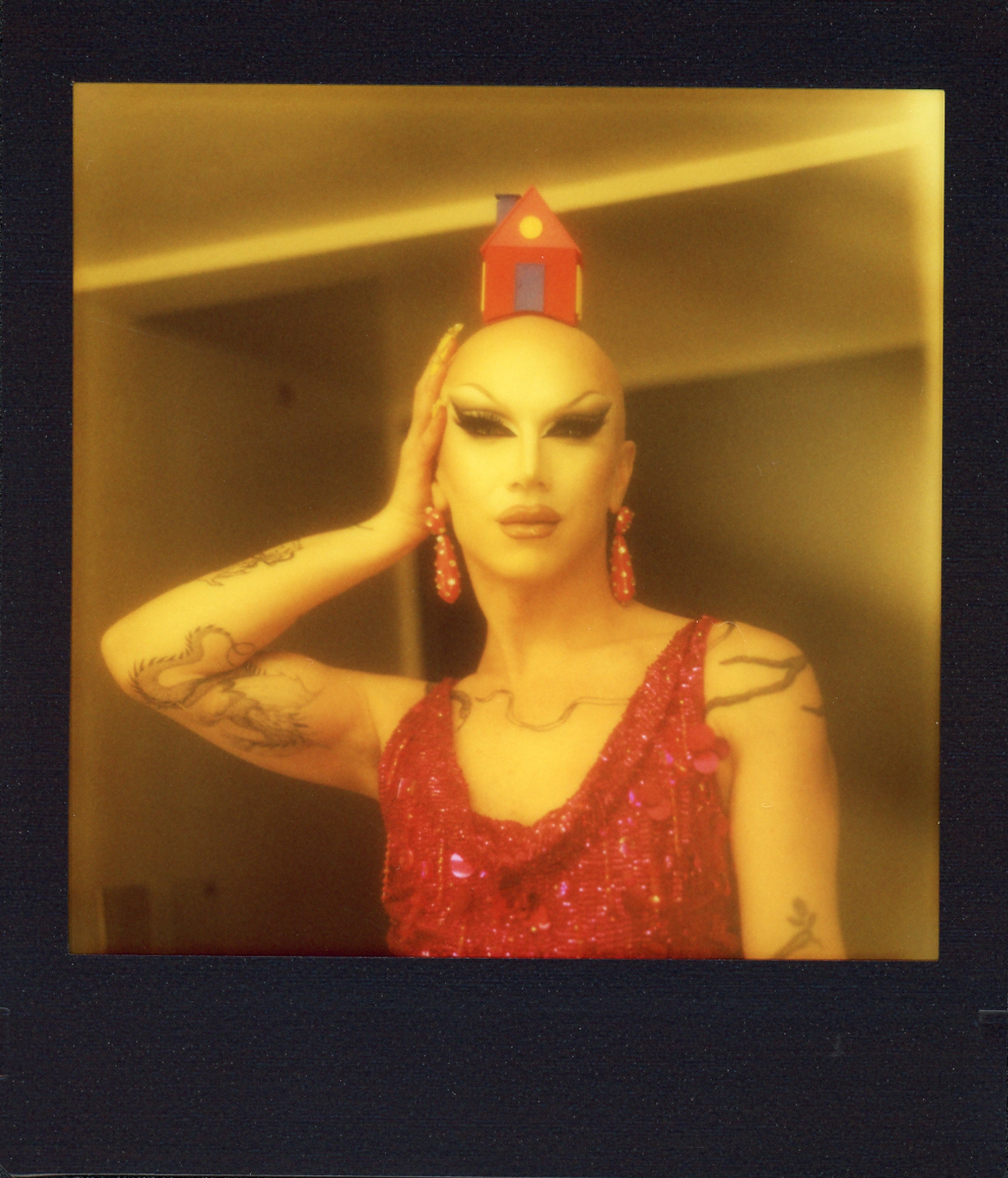

Sasha Velour Delivers a “Long Drunken Drag Bar Speech”

On season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race (which she ultimately won), Sasha Velour developed a bit of a reputation. She was called the face of Brooklyn drag, with performances that were both artsy and extremely studied. And it’s true: Sasha Velour is a glossy, living piece of art, but she also thinks deeply about who she is, what that represents, and the impact she can have. This all crystallizes in her new book The Big Reveal, which is part-memoir, part-drag history, part-manifesto, addressing queer expression and gender variance at the macro level, literally beginning with the Mesolithic age, and also the micro, sharing intimate details of her post-Drag Race reign.

The Brooklyn-based performer previously self-published a magazine called Velour, which ran for three issues and is now available as a hardbound 300-page tome, and a self-illustrated comic based on the Stonewall Uprisings. The Big Reveal, her latest literary venture, is a thoroughly researched and at once, heartfelt, earnest and slightly radical book filled with stories that bring into sharper focus the person behind the cerebral drag persona. Velour is as unapologetic about the bias that comes with being a drag queen writing about drag history as she is about the scope of her own influence: as she tells it, Lady Gaga’s team once reached out to designer Diego Montoya to borrow three of Sasha’s looks for her Las Vegas residency, not knowing that Sasha herself owned them. Shortly after the publication of her book, which she likens to a “long, drunken drag bar speech,” Velour sat down with me to talk about why it’s important to write oral histories,, the possibility of adapting Mae West’s The Drag, and why you might detect a little bitterness as you flip the pages of The Big Reveal.

———

MIKELLE STREET: You’ve said you wrote this book because it’s the book you always wanted to read. But how did you get started?

SASHA VELOUR: I had this document that I had been working on for many, many years. I would put little bits into NightGowns speeches, little bits into other numbers just trying to chart figures from the history of drag that, to me, painted a picture of the radical art form and this gender expansive art form that I felt like I wasn’t getting from the typical histories. Especially the ones that I felt were so focused on the 21st century only or American and British drag only. I was developing the story from different sources. I think that was the real beginning of the book and I ended up submitting that with some of my own stories. The book sort of evolved from those two separate working documents.

STREET: Were they always one project?

VELOUR: I did kind of always have the idea of it to be one project, but I wasn’t always sure I could pull it off. I had a vision of a history book and a personal memoir at one point, but then I kind of wish all historians would talk about how they came across things personally. It kind of blasts apart any claim to objectivity when you show how you came across information and it shows your concerns and your process and your questions—that kind of makes sense to me. It also seems like a draggy way to do it too, where you ground everything in your experience and the personal story of it all.

STREET: In many parts of the book you credit your mom and your grandmothers for their impact on your drag. But reading it, I wondered if you were also impacted by your dad, and how he writes about history.

VELOUR: I think so. I mean, my dad writes for a very academic audience. He’s a historian of revolutions and of workers’ revolutions, and I think drag is one of those, an ongoing worker’s revolution. But yes, the idea of centering individual stories as a way of telling history, I definitely grew up around everything being told in that way. I just had the first event of my Big Reveal book tour and invited my dad to come on stage for a conversation and he believes, as a parent of a queer person, that these stories—either from your life or from history—have the power to change people’s minds and break apart misconceptions and myths. So there’s this political quality of people’s history from that side. Especially thinking about what we need to clear up about drag and about queer and trans life, I think focusing on those stories is important. And I can’t tell any story as truthfully as I can tell on my own, so I felt like that was the strongest way to go.

STREET: So much of queer history, and drag history by extension, exists as oral history, so I’m curious why it was important for you to put these stories to text.

VELOUR: I think written archives have enormous power. And, obviously, queer stories have been destroyed and erased before, but hopefully the more we can get into print and on the record, that changes what people have access to and how we can see ourselves and how we can give ourselves context. That certainly helps in finding the facts to back up our normalcy or our belonging in the world, and even gives us strategies of resistance and survival. But I did just want it to read like an oral history because I love that tradition. This is just like, a long, drunken drag bar speech. It’s the kind that I’m always craving and that many of my Brooklyn drag legends have been known to do. We absolutely impart those stories in our own drag-made spaces. I just wanted to capture that in a page.

STREET: You write about a lot of queens that were important in both drag history and your personal history. Does any one stand out?

VELOUR: There are so many. In my first discovery about drag and my desire to call myself a drag queen, it was specifically Jose Sarria, who founded the Imperial Court system, and Sylvia Rivera, who obviously led queer and trans liberation and calls herself a drag queen. Even Barbette, to a lesser extent, who was a Texan aerialist. But researching the book I came across figures that I hadn’t learned about, specifically Kewpie in Cape Town, South Africa, who had this hair salon and cultural space for people dressing up the drag, for trans women for decades. They had all of these photos in their archive and were really happy for me to use them for the book. To be able to see her from being a young person to being older was so moving. Throughout the process of thinking about the stories of drag artists being able to age and still exist and keep doing keep doing drag is such a privilege. That’s why in the comic at the end of the book I drew myself as an old lady. Because that’s the queer utopia we can dream of: being able to become a grandma of the drag community.

STREET: You seem quite methodical and extremely intentional. So to me the book ends up being this sort of “vegetables in the mashed potatoes” situation where you provide Drag Race fans with the tea they want, but none of it is provided upfront. Was that intentional?

VELOUR: I’m glad that it’s working! You know, it’s there, but it’s buried enough that they have to stick through the whole context. You don’t just get the rose petals. I feel like when a drag queen is putting on a show she has control of the flow of information so I couldn’t just give it all away. You have to stay with me for the whole journey.

STREET: This is a very trite question but, given your famous drag reveals, is there something you wanted to “reveal” with this book?

VELOUR: I have always been on a mission to combine all these “different” histories of drag. So, sort of like the trans drag history, this pageant history, the underground party history, the radical ballroom history. I see that they all are deeply connected and I wanted to describe drag in such a way that made sense because I do think we need to be united. But I also think I wanted to reveal some of my own personal, my own real, human questions, doubts, and frustrations behind the scenes. I think it’s so tempting to perform perfection. Many of us feel like we have to in order to be valued as queer people, as drag artists. We think that’s what the audience is looking for. Writing the book kind of gave me permission to stop performing that full perfection.

STREET: It felt very personal and human and, in some moments, like there was a hint of deserved bitterness, not this sort of glossy veneer.

VELOUR: I love that adjective: glossy. I think I feel like it’s my job, a little bit, to be kind of glossy. Whether I’m hosting a show or in my public persona, but backstage we’re all kind of bitter and honest and real. I was trying to bring that to the book. The format helped because writing is a little less performative.

STREET: What do you want to do next? Are you looking to do another issue of Velour, or something different with NightGowns?

VELOUR: I’m always looking to take NightGowns around the world, so I would love to have that happen. I’m also always constantly threatening my partner Johnny with another issue of Velour. I think it would be cute and it was so fun to do. It really connects us with a lot of people. I’m also working on two other projects: I want to write a scripted TV show about drag and I have been working on that for a while. I also am developing a show with Tectonic Theater Project. We are kind of working on a show around drag history, kind of in connection to the book, so I’ve been learning aerial in the style of Barbette with the hopes of flying in the air.

STREET: Speaking of theater, I was recently reading about Mae West’s play The Drag and thought “ould ever stage this production today?”

VELOUR: I feel like I just heard a story about someone doing a Mae West production recently, it wasn’t The Drag but it was something else. But I feel like that would be fantastic. I’d queer it up even more. I think it got shut down immediately after or during one of the performances so if we did it now I’d definitely want to build that into it. That would make it more legendary.

STREET: Last question. What’s the one thing you’d like readers to take from The Big Reveal?

VELOUR: There’s something I wrote in the first three pages. I put it there because I was thinking if you only get this far, I want you to get this. It’s that I think drag is a feminist art form and that if the world could accept drag as a form of art and natural expression, society would be invested in true equality for people. All genders, all people. Drag, truly done properly, preaches freedom for all.