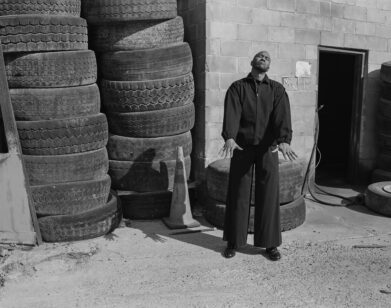

Sarah Paulson and Sally Talley

ABOVE: SARAH PAULSON AND DANNY BURNSTEIN IN TALLEY’S FOLLY. IMAGE COURTESY OF JOAN MARCUS.

There are no special effects in Roundabout’s revival of Talley’s Folly. No scene changes, no dramatic exits, and no intermission; just two characters trying to relate to one another. Set in Missouri on July 4, 1944 and written in 1979, Lanford Wilson’s play is the second in his Talley trilogy. Matt, played by Danny Burnstein, has come to ask Sally (Sarah Paulson) to marry him. A Lithuanian-born, 42-year-old Jewish accountant, Matt is not the Talley family’s ideal match for Sally, but then neither is Sally herself. At 31, Sally is outspoken, independent, and 10 years too old to be unmarried. Like Matt, she is stiff and awkward in her own skin.

You might not be aware of it, but you have a favorite Sarah Paulson performance. Perhaps it’s as Elizabeth Olsen’s bewildered sister Lucy in Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011); the independent magazine editor Vicki Hiller in Down With Love (2003); the crippled Laura Wingfield opposite Jessica Lange in The Glass Menagerie on Broadway (2005); Sarah Palin’s overwhelmed advisor in Game Change (2012); or the trapped journalist Lana Winters in American Horror Story: Asylum. A careful character actor, Paulson has been delivering solid supporting performances on stage, on television, and in film for nearly 20 years. With two high-profile projects coming out this year, Steve McQueen‘s Twelve Years a Slave with Michael Fassbender and Brad Pitt and Jeff Nichol‘s Mud opposite Matthew McConaughey, perhaps Paulson will finally get the attention she deserves.

EMMA BROWN: I just saw Talley’s Folly, and you’re onstage for the entire play. That must be exhausting.

PAULSON: [laughs] It is exhausting. I’ve done it one other time. I did a two-character play, or a two-hander as they like to call them, with Linda Lavin on Broadway two years ago. A Donald Margulies play called Collected Stories (2010). This play is very different, though, because there are no intermissions. Once you enter the stage, you never leave. In [Collected Stories], it was just two characters, but there was Act One, Scene One. We got to have blackouts. We would have scene changes. You have a second to get your head around about what you’ve got to do next in the play. This is, ostensibly, a 96-minute scene—there aren’t any set changes or blackouts. It’s just one continuous thing to play. Energetically, it’s harder to do than I anticipated, for sure.

BROWN: Are there ever moments when you feel like, “I really don’t want to be onstage right now, and we have another 37 minutes to go”?

PAULSON: [laughs] It’s not about, “I don’t want to be onstage right now,” and more about, “I could use a sandwich,” or, “I’m really thirsty,” or, “I kind of have to pee,” and there’s just nothing I can do about it.

BROWN: How do you get yourself back in to the play when that happens?

PAULSON: It’s just a kind of flash. It’s a thing that Danny Burstein’s character talks about in the play—Lanford Wilson writes this great thing about the idea that the brain can work on 10 tracks all the time. That’s sort of what happens when you’re doing a play; you’re fully engaged, and yet you’re also thinking about the moments that are upcoming, you’re also thinking about how you’re hungry, you’re also thinking about how you have to do it again on a two-show day. I think of it like meditating: you let your mind wander for a second. In a play like this, you don’t have much time. That’s part of why it’s more tiring than other plays that I’ve done. To stay focused, you have to rein a lot of your thoughts in. It’s hard.

BROWN: Do you have a favorite moment in the play?

PAULSON: I have so many of them. I was not well-versed in the plays of Lanford Wilson prior to doing this and I can now say that I am absolutely a complete, obsessed Lanford Wilson person now. I’ve never been very comfortable as an actor looking out into the audience; I always like to keep my focus on the other person. When you start playing out to the audience, it takes me out of it, because people don’t do that when you’re in life behaving with another person—you don’t often look out, around you, in a presentational manner. With this play, because we’re outdoors, and the night is part of the play, the evening itself, the sounds, I’m getting more comfortable using the fourth wall as a character. I’ve never done that before. I do love that.

BROWN: If Talley’s Folly were set in the present day, do you think your character would have already married someone she met through Internet dating?

PAULSON: [laughs] No, I don’t, because her inability to marry has nothing to do with the dearth of men. It has to do with her belief that she’s broken and not a viable mate, not worth anything. When your own father decides that you’re not worth much… There’s a great mystery to her. The idea that her father sees her as a pawn in a game of commerce is a hard thing to shake if you’re a woman, or a human, at all.

BROWN: You’ve been doing plays for a long time now; would you ever stop doing theater in favor of movies and television?

PAULSON: Never, never. I will do plays as long as they’re interested in having me do them. It’s the biggest opportunity to learn the most about how to act. Something I discover every time I’m doing one is how little I know about acting—how important the art of listening is, and how important it is to listen with your entire body. You can tell so much of a story with stillness, and a lot of that can be from really actively listening to your scene partner. I feel very blessed on this one, because Danny is so extraordinary.

BROWN: Did you know that he was going to be involved when you signed on?

PAULSON: I did. They had him before they had me, and that was one of the reasons I wanted to do it.

BROWN: I’d want to know who the other actor was before I agreed to do a two-person play.

PAULSON: Yeah, and that’s why Danny is so brave, because he said yes before he knew who else was going to do it. He could have been stuck with some—maybe a better actress, but maybe not such a nice person.

BROWN: I know you’ve signed on for Season Three of American Horror Story, and you will be playing a new character. Do you get any input into who you’re going to play?

PAULSON: I wish. I would do anything they tell me to because I trust Ryan Murphy, but I hope I have stuff to do with Jessica [Lange]. She’s my favorite person to act with. The more stuff I have to do with her, the better. We did The Glass Menagerie together on Broadway in 2005. Every single person that’s coming back will be a completely different character. It’s another story, it has nothing to do with the previous year or anything before that. I don’t know what I will be playing, but I know I will not be playing Lana Banana.

BROWN: Did you know that Jessica was a part of American Horror Story when you signed for the first season?

PAULSON: Yes, I certainly did. I only did three episodes the first season. I had a long friendship with Ryan preceding that, but it was really because I was with Jessica at a dinner for Project Angel Food—Ryan was there and Jessica said, “Put something for Sarah on the show.” And he said, “Oh, I have an idea.” And it was that part that I played the first season, of the psychic. So, I really credit her with reminding him about me.

BROWN: I also recently watched your new film Mud, where you play a mother in Arkansas. Do you remember the first time you had to do a Southern accent for a role?

PAULSON: It was actually my second professional job ever. There was an Al Horton Foote play at the Signature Theatre called Talking Pictures. I had a Southern accent in that play, and I was 19 years old.

BROWN: What was your first professional part?

PAULSON: My first-ever job was right out of high school. I got a job understudying Amy Ryan on Broadway in The Sisters Rosensweig. Amy booked a trip to Paris with her sister—I had been understudying for eight or nine months. She couldn’t change the ticket, so I got to play two weeks of the show.

BROWN: Having been an understudy, do you take pity on your understudy? Do you ever purposely take sick days to give her a chance?

PAULSON: [laughs] I would like to, because I know what it feels like to really want to get out there, because I have been one. I want to give her a shot at it, but at the same time, they’re going to have to drag me out of there kicking and screaming. I don’t feel bad for them, because when I was an understudy I was very glad for the job, and I loved being around all the people and the ritual of coming to the theater every day. But I understand the idea of being really frustrated and wanting to get out there and having all kinds of ideas about how you would play it.

BROWN: Do you remember your first non-professional role?

PAULSON: I was constantly, always and forever, trying to perform the musical Annie for anyone who would listen, and I have a terrible singing voice. It was the first thing that made me think I wanted to be an actress. I would go around telling people I had auditioned for the movie and fabricated a whole lie, a big fat lie story, about how I was very close to getting a role in the movie.

BROWN: Did people believe you?

PAULSON: Oh, yeah. Because I moved to New York from Florida, so I had concocted that I had been to an open call in Florida. When I moved to New York, nobody knew me, so for all they knew, it was true. It was a big lie—a big foreshadowing to my life as an actress.

BROWN: You could be in Annie now!

PAULSON: If you heard me sing, you would just plug your ears and run, screaming, the other way. I promise.

TALLEY’S FOLLY OFFICIALLY OPENS MARCH 5 AT THE HAROLD AND MIRIAM STEINBERG CENTER FOR THEATRE IN NEW YORK CITY. FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO PURCHASE TICKETS, VISIT THE ROUNDABOUT THEATRE COMPANY’S WEBSITE.