Sarah Hall’s Violent Femmes

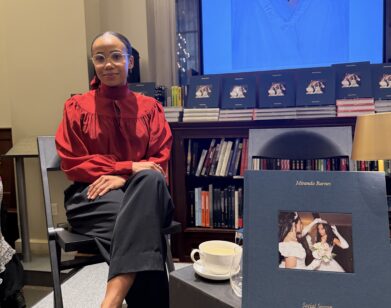

ABOVE: SARAH HALL. IMAGE COURTESY OF JAMES EMMETT

Sarah Hall’s sexy short-story collection The Beautiful Indifference (Harper Perennial) is brooding and beautiful. From bullies in the north of England to long-distance lovers’ rendezvous, from a shockingly supernatural and violent vacation in Mozambique to a chic sex club in London for bored housewives, Hall presents unique situations with uncannily human candor. Moody, mysterious, and often melancholy, Hall explores the depths of our deepest and sometimes darkest human emotions: love, death, sex, betrayal. On a seemingly idyllic lake in Finland, a woman chooses between saving herself and her drowning lover; in a remote town, a young girl becomes obsessed with her bully classmate, with bloody consequences. Hall makes danger deliciously, poetically seductive. We spoke with her in London about violent fantasies, love on vacation, secret sex, history of place, and murder.

ROYAL YOUNG: Sometimes violent people are awful, but sometimes they do things we may want to act out, but can’t.

SARAH HALL: A lot of my literature deals with these people who are somehow magnetic because they have that ability to step over lines. I was brought up in the north of England, which is probably no rougher than anywhere else, but I remember as a child being kind of mesmerized by girls fighting on the playground. My first story deals with a teenage girl being really enamored by another girl whose family is really inclined that way. The teenage years are interesting because you’re moving away from violence into a more intellectual realm, but passions are still running quite high. The girl in that story sees this family still living by these sort of ancient code of violent values and she reads it as strength. It’s quite seductive, but you fear for her.

YOUNG: I think if you possess that level of violence, you can’t be a self-aware person. And once you’re self-aware you have more inhibitions because you’re analyzing everything you do. That’s kind of sad. Sometimes I wish I could just hit someone. [laughs]

HALL: [laughs] Yes, you can’t exactly walk down the street and just hit someone in the face for no reason. That’s a very interesting point, about being self-aware. As a writer, you’re able to set up characters where they play out violent fantasies. Wouldn’t it be great if everyone you hated could be hung upside down in a barn and whipped with a riding crop? Well, no, it’s dreadful. But as a writer, you have the liberty to act these things out on the page.

YOUNG: Do you think violence haunts places or people? Once violence has been committed, does it leave an imprint that is carried on?

HALL: One of the things I try to do with my writing is try to evoke the spirit of the place. I think these things imprint on the landscape and the culture. Particularly the north of England and Scottish border is very historically violent, where the monarchy just turned a blind eye. They actually at some points encouraged this, because they thought it would cleanse the landscape of these terrible feuding families. London and New York can import different cultures, but in these rural valleys you find old echoes of the past.

YOUNG: I was born in New York and my grandparents were raised in the same downtown area, so I’ve seen it through so many changes. The history becomes a history of change. But in rural places, change comes so much slower.

HALL: Exactly. That’s a great way of looking at it. In the UK now, there’s a feeling that a lot of country places are less understood. Representation from these areas, not that they have less worth, but they seem more exotic. My writing is called exotic or avant-garde because I write about rural places. Has it really come to this, that if you write about the country you are avant-garde? How did this happen? Modern agriculture and spaces are still so relevant. Are wild spaces just gardens of the city or are they not?

YOUNG: I wanted to talk with you about love on vacation. How that completely changes the shape of a relationship.

HALL: When you’re with someone, the first time you travel is a big thing. Any security net that is sprung under the relationship is gone and you get to know someone in quite an intimate way. You think you’re secure. You’re going on a nice holiday to Finland and it’s flowering and beautiful, but actually this is a wilderness that this couple finds themselves in. They’re still madly falling in love in the early stages. When you set relationships against a landscape, you can find out how they really feel about each other.

YOUNG: There’s that aspect of love on vacation. And then you wrote about a long-distance love, where you’re always on vacation when you’re together, so you never get a change to discover how you really are.

HALL: Yes. They only get to spend time in hotels. It’s a strange limbo and it creates something that works in those moments, but has no reality outside it. It seems that in modern times, people compartmentalize their lives and seem to find relationships that work for them which are part-relationships. They remain undergraduates in romance, having a little bit of something and being too afraid to express more. They’re almost like addicts.

YOUNG: Sex changes a lot when it’s secret.

HALL: Certainly, this trick of not getting to know somebody. Things work best when your partner is a semi-stranger. And the couple in that story has found a way to maintain that. It will work for while until one of them wants something different. It’s nice to think we all fall head over heels in love, but that’s too simple. The only way to get over a relationship pretty quickly is to murder your partner. Writers are always testing things, making hideous, terrible Frankenstein-like scenarios.

THE BEAUTIFUL INDIFFERENCE IS OUT NOW.