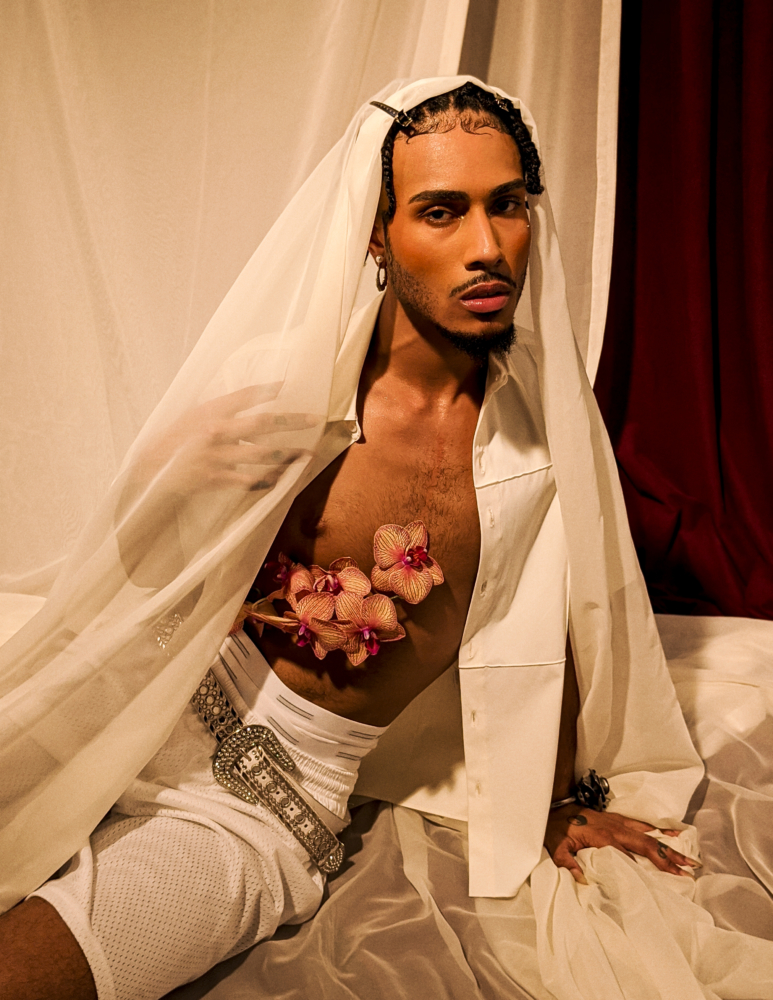

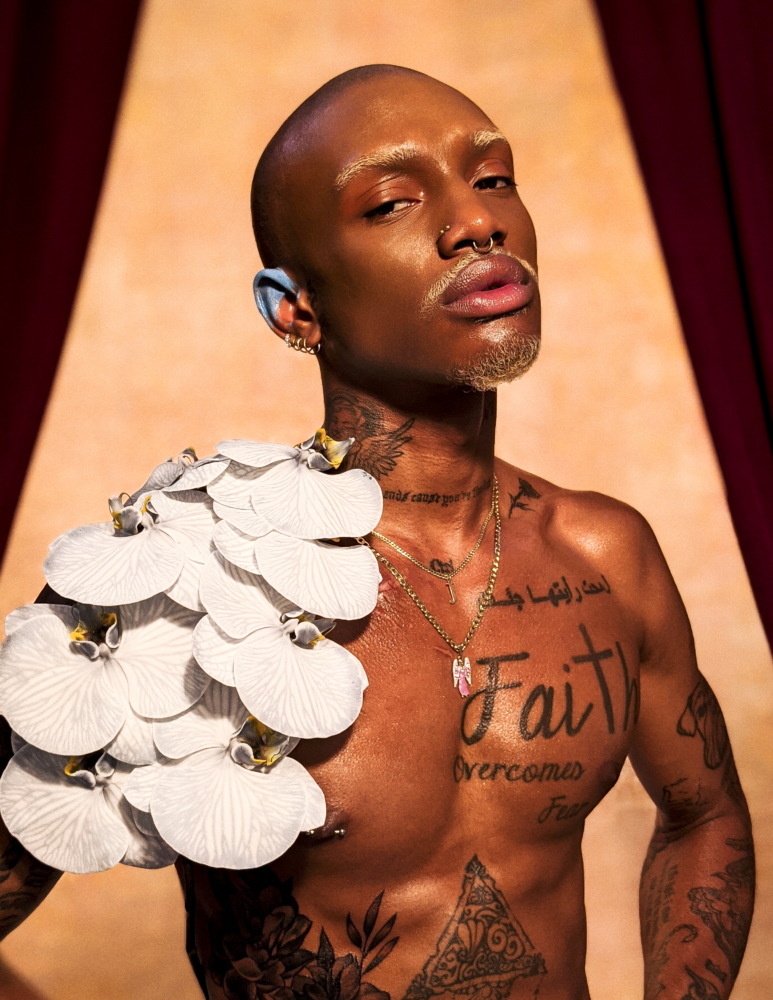

Quil Lemons’s New Vision of Black Masculinity

As Quil Lemons could tell you, it’s no easy task to find a Black Ken doll. “You’d think it’d be more easy in Brooklyn,” the photographer says. But once he finally found it, he decided to disrobe it, dismember it, and shoot it. “I was putting the head in between the thighs, and just kind of pushing the boundaries of what we think is socially acceptable. On Instagram, you can’t post any nude images, unless it’s a doll or a figurine or, like, ‘art.'” Lemons, who is Philadelphia-born and Brooklyn-based, is best known for soft, supple portraits of people of color in circumstances rarely afforded to them in popular imagery. Lemons’s 2017 photography series “Glitterboy” offered a glimpse into the kinds of vibrant worlds he could imagine. With “Boy Parts,” his most recent endeavor created with the help of Google Pixel and LENS’s Creator Labs, that vision is now a reality. In the series, Lemons combines references to Kehinde Wiley, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Renaissance portraiture in an effort to unpack and reimagine masculinity. Like fellow Creator Labs alum MaryV Benoit, Lemons utilized the program to explore themes and subjects that are at once deeply personal and highly political, something he considers a more serious responsibility as his artistic vision has expanded. Below, Lemons discusses his dream subjects, his hopes for the future of Black artists, and his thoughts on subverting—and surpassing—gender bias.

———

“I feel, being a Black man, as if we’re always in some kind of paradox or a clusterfuck of trying to figure out who we are and what that means in relation to other people. It’s constantly changing. I want to capture the idea of code switching—if that wasn’t a thing, if Black men and Black people in general didn’t have to constantly morph into a different person based on the context of their surroundings, what would that look like? That’s how I handled the question of unpacking Black masculinity—if it was free and didn’t have limitations based upon societal standards, within the Black community and outside of it. What would Black masculinity look like if it was able to be fully free and not tainted by whiteness, if it wasn’t being monitored and policed by that colonialism?”

———

“My mom looked at it and she was like, ‘They’re obviously gay.’ And I’m like, ‘Are they?’ I don’t think wearing flowers is indicative of their sexuality. Perception has nothing to do with what’s going on in your bedroom. It’s interesting that Black men aren’t allowed to touch femininity at all without being perceived as gay. I thought that was an interesting tension.”

———

“When I get behind a camera, I’m making images for myself. But I realized, once it reaches this larger, global conversation where people are asking me questions, I’m really aware now more than ever that I have to be really responsible about the things that I’m making. I get messages from people all around the world, like, ‘Oh my god, I feel seen by this,’ and I take that responsibility very seriously now as a creator. So, I’m really thinking about, ‘What in the hell do I have to say?’ I’d rather not say anything than to just throw something out there that’s half-assed, or that doesn’t have my voice.”

“I would love to meet Jackie Nickerson and shoot each other. I was probably, like, 15, when Kanye did his first Yeezy season and she shot all the zines for it. I grew up immersed in her photographic world and loving everything she does with this real, dark, cold lighting, which is so different than my lighting because I’m always super warm and bright. I would want to shoot Hunter Schafer from Euphoria, Kid Cudi, Carrie Mae Weems, and Mickalene Thomas. Mickalene and I had a conversation for the Aperture book and she’s been a big supporter of my career since its inception. I was exhibiting during Contact Festival during 2017, with these billboard size prints of my ‘Glitterboy’ series. She and her wife put it on their Snapchat and were like, ‘Oh my God, we want to meet you.’ I’m like, ‘I’m actually here in Toronto right now. Like, can we link up?’”

“None of my work has been deliberately political, but everything about my entire existence is kind of political, which is such a weird place to make art from. Sometimes I just want to make art for the simple sake of making art and not have it be, ‘Oh, you’re defying these gender norms,’ or, ‘He’s recreating this new thing of Black masculinity.’ Being a Black creator, you have to be hyper mindful, and in some ways it’s kind of annoying because I feel like it’s not the same for my white counterparts. They just get to create so many worlds, and I have to create my world, but also bring politics into it. Which is fine, because I can definitely do that and I rise to the occasion every time. It would be nice to be able to create art for the sake of just making art, versus making art and then it being compounded with so many political statements.”

“When I was 18, I thought I was going to go to school and become a photo editor. I think it’s still something I want to do, because it’s such an important job and people don’t pay enough respect to that. They are the ones dictating who gets to be in what publications and are kind of like, gatekeepers, if that word still even holds true for today. I don’t think a lot of editors are tapped into what’s happened culturally, and I don’t think enough people tune into what’s going on in the Black community. There’s so many people that should be on covers of magazines that are not. I think we need to start creating institutions for Black creators and artists and entrepreneurs to put things into making all-Black museums with all-Black art. My personal goal for myself is to get into the Whitney or MoMA by 25. I’m 22, so I’ve got three years. I’ve really got to get going.”