Kanye West Refused to Pose for Photographer Heji Shin

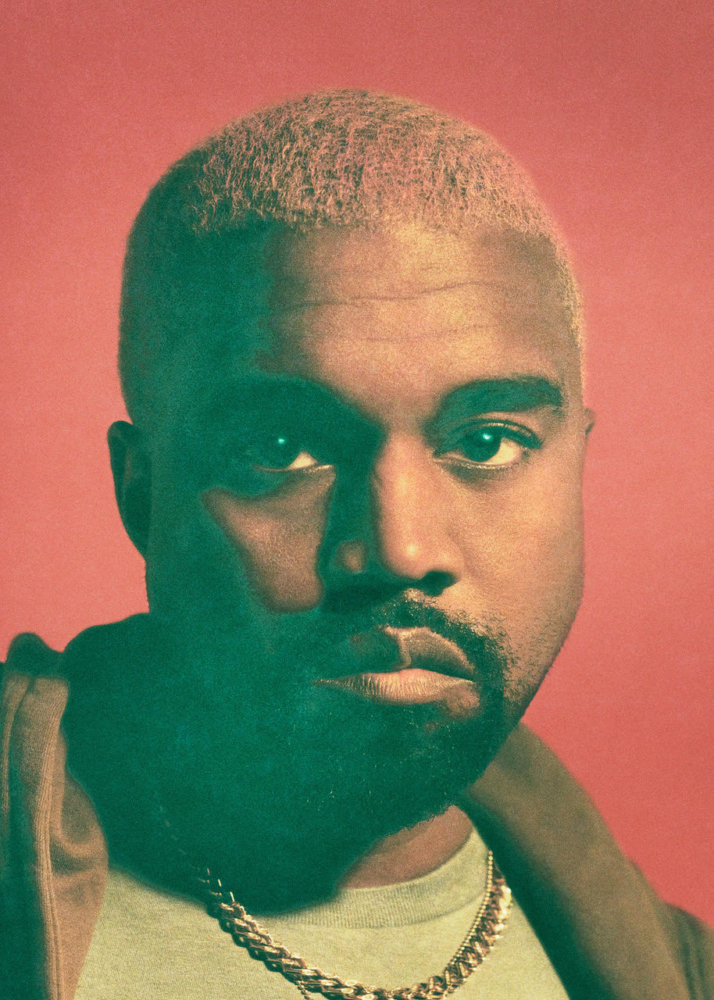

“Kanye VIII,” 2018.

The New York–based, German-Korean artist Heji Shin has built her career on portraiture—and provocation. Cue the campaign she shot for Eckhaus Latta featuring real couples having sex, or her series of infants photographed exiting the birth canal, or her show “Men Photographing Men,” which opened at Reena Spaulings last year at the height of #MeToo. In her new solo show, Heji Shin, on display at the Kunsthalle Zurich through February 2019, the discussion boiling around Shin’s ten billboard-size portraits of Kanye West—alongside three less discussed x-ray portraits of the artist herself—is just a logical extension of her work. “I knew I wanted to do something about this masculine energy that everyone has such a problem with lately,” Shin explained. “I also considered asking Hillary Clinton. But a friend had a contact for Kanye, so I wrote to him and simply asked.” West agreed, they met up in Chicago, and he suggested she photograph him on the spot. But Shin refused. She wanted studio shots. A week later, Shin was on a plane joining the Kardashian-Wests on a family trip to Uganda. There, she snapped some candid images, including one that made the Zurich show, but she needed West in a studio, looking directly into her lens. Shortly after returning to the States, she got her way, and a series of portraits that explore, as the show’s press release reads, quoting Virginia Woolf, the “difficult business of intimacy.” Interview spoke with Shin in the days before the show’s closing about the ways in which this slippery business is conducted, celebrity as a screen for the public’s hatred or desire, and how being a good subject for the camera is a bit like being a “power bottom.”

———

CAROLINE BUSTA: What were some of the reactions to the show that you didn’t anticipate?

HEJI SHIN: I didn’t anticipate getting tons of negative reactions. I thought people would have more humor. But they could really only see one layer of the work, in terms of current social-political terms.

BUSTA: You mean like Kanye at the White House wearing a MAGA hat?

SHIN: It’s what’s been implied in all of the comments. The idea that I shouldn’t be giving him a museum platform—or he giving me one. But this idea of “giving somebody a platform” or of “deplatforming”—the approval or disapproval of an artist’s values—if you can only see art in these neoliberal, transactional terms, your overall worldview is likely not far from this perspective.

BUSTA: The Kunsthalle Zurich is an incredibly well-respected institution, but the scale of its audience versus, say, Kanye’s own Twitter account is so asymmetrical that the idea of you giving him a platform—I mean, Kanye is a platform.

SHIN: And this contrast is, of course, interesting in the first place.

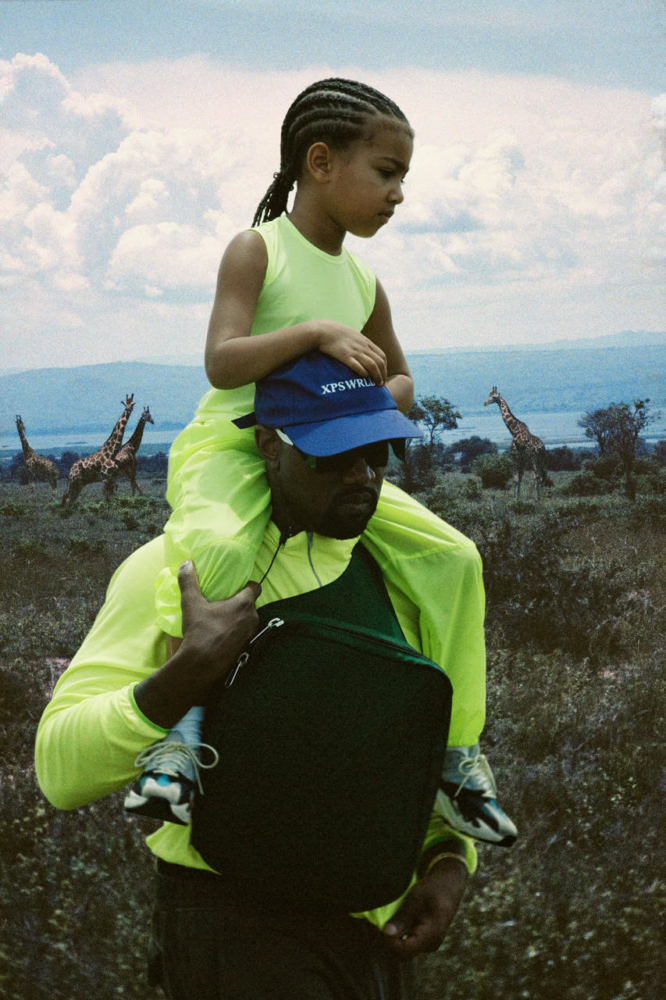

“Kanye,” 2018.

BUSTA: If it hadn’t been Kanye, though, is there anyone else you would have photographed instead?

SHIN: Kanye was definitely my first choice. I was thinking about how the kind of masculinity he represents seems to be regarded as something threatening. But the possibility was so small that he would agree. I was also considering Hillary Clinton. They have nothing in common in terms of personality—

BUSTA: But it’s not even about that, right?

SHIN: It’s not about personality. It’s not about political stance. I mean, it is about both of those things, but more in the sense of what people perceive. With Kanye, there are two very different narratives going on. If you dig even a little bit deeper, it’s hard to find a single super-controversial or bigoted thing. With Hillary, it’s a little different, but she has the same—

BUSTA: They’re both projection screens, for love and hatred.

SHIN: And for me the hatred is more interesting, at least in terms of making art. Some people feel that art should contain social utility, or that art should be required to meet certain moral and political standards, but then what you end up with is propaganda. I wish these people would just openly admit that they hate art.

BUSTA: We’re seeing people freak out about the morality of art at a time when many feel their own grip on history—let alone the future—slipping. For these viewers, canceling art, asserting their veto power over it, isn’t just exciting, it’s fundamentally cathartic. But in these times you need art to push farther than ever.

SHIN: I totally agree.

BUSTA: The Kanye portraits aren’t the only works in the show. You also include three x-ray prints of yourself holding lap dogs, as if you’re saying, “Go ahead, read me to the core, full transparency,” but you’re actually completely unrecognizable. By contrast, there’s the single candid portrait of Kanye, the one taken in Uganda, with his daughter on his shoulders. Even though he’s wearing sunglasses and an XPSWRLD cap, you can’t really see his facial expression because of the tones of the print. There is so much human information in the frame. Here is Kanye in the world as a father. It’s the most intimate image in the entire show.

SHIN: That photo was not staged, or constructed at all. The x-rays, they were completely. And yet, in both instances, you have the promise of seeing something more and neither gives it to you.

“X-rays,” 2018.

BUSTA: You started shooting portraits for news media and other commercial outlets more than a decade ago, right? How has portraiture changed for you since social media took off?

SHIN: I’ve never really thought about it. I guess I’ve always explored how far I can go with a person, how far I could take an idea. Early on, I was working for an economics magazine, so the spectrum was limited. But even then, when you’re shooting another person, there’s always this psychological game: How much does the subject trust you? How much do you want to direct? There’s manipulation—in both directions. That hasn’t changed. And I think the person who gets photographed is still very willing to submit to the photographer.

BUSTA: True. As a portrait photographer, you’re putting your subject in a submissive position just by putting a camera in front of their face, and yet what you’re asking them to perform is dominance.

SHIN: That’s really interesting, because this was exactly the challenge Kanye and I had. He’s very aware of this dynamic between making images and being made into an image, and he felt uncomfortable being directed. I could identify with him. For instance, he told me he wouldn’t do poses. He would only look straight ahead into the camera.

BUSTA: So he said, “You can shoot me in the studio, but here are my terms.”

“Some people feel that art should contain social utility, or that art should be required to meet certain moral and political standards, but then what you end up with is propaganda.” —Heji Shin

SHIN: Exactly. But I can relate. I once got photographed for a fashion magazine, and the photographer asked me to put my hand on my hair and pull it up in some pose I would not do. And I said, “No, I’m sorry. I’m just looking straight into the camera.”

BUSTA: In your Kunsthalle Zurich show, there are portraits of both of you: larger-than-life portraits of one of the most iconic, hetero male figures in pop culture and a few small pictures of a half-invisible you. To me, the “object” of this show is not the photo series but the unspoken male gaze, which by the mechanics of portrait photography becomes submissive to you, the photographer.

SHIN: Or to the camera, because there’s also this huge lens. You don’t see a face, and it requires strength to let go and put the control in somebody else’s hands, to submit. But to be good in front of the camera, you have to be a really strong-minded person and very creative, too, like a power bottom. But sure, the dynamic of a female, non-white person photographing this very masculine, outsize personality is something you do think about in this show. I try to approach it in a more ironic way.

BUSTA: I feel like this work arrived at the exact time when most people feel strongly that you can’t speak about “X” unless you prove that “X” is what you are.

SHIN: People write to me every day on social media saying, “How could you do this show?”

BUSTA: Yes, I think we’re in an age of unprecedented cultural policing and one with no option for absolution, which is a problem because every society has to have a way of collectively dealing with the fact that we all fuck up all the time and do need a way of absolving each other.

SHIN: It’s easy to agree with publicly approved opinions. You get to disappear into the group and assume the group’s identity, which is probably a comfortable and safe thing to do. Doing this protects you.

BUSTA: Are there any references you that are helpful for navigating our current moment?

SHIN: Shrek 6.